Introduction

Logical development of any branch of mathematics depends on a set. The elements of the set are underfilled terms. Associated with them are certain statements which are taken as axioms or postulates for the subject.

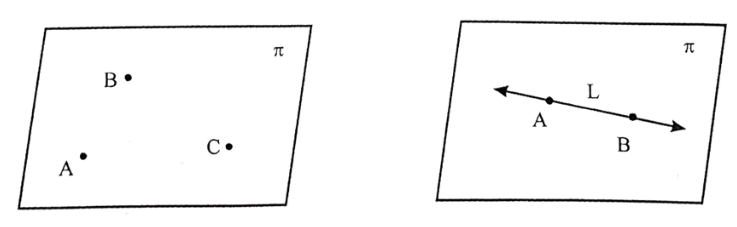

In earlier classes, the set language was used for the effective understanding of geometrical concepts. It may be recalled that the structure of geometry was developed by taking point, line, plane, and space as undefined concepts and that every geometrical figure is a set of points.

Solid analytical geometry (Three-dimensional coordinate geometry) is a subject redeveloped on the above lines. The study of quantitative and qualitative nature of space very much depends upon coordinates and algebraic operations and methods associated with it. Also, vectors as ordered triads have an application in the treatment of solid analytical geometry.

We take a set S and call it the 3-D space, \(R^3\) – space and its elements the points of the 3-D space. We take line L, plane π, sphere S, etc. as subsets of S.

If P ∈ L, we say that P is a point on the line L, i.e., line L passes through the point P. If P ∉ L, we say that the point is not on line L and does not pass through point P.

Points on the same line are said to be collinear and points on the same plane are said to be coplanar. If L ⊂ π, we say that L is a line in the plane π i.e., the plane π contains the line L. Further, L ⊂ π implies L is not in the plane π.

We give below, not all, but certain axioms, definitions, and theorems (without proofs) of Euclidean geometry which have wide application in solid analytical geometry.

Further, some well-known terms and concepts which are used in the development of the subject and which have to be redefined are deliberately left out as their definitions and the results involving them given out in earlier classes are true even here.

Introduction To Planes In Geometry With Examples

1. Axiom. One and only one line passes through two distinct points.

If A, B are two distinct points on L, we say that L is the one and only one line which passes through A and B. We write L as \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\).

2. Axiom. One and only one plane passes through three non-collinear points.

If π is a plane passing through three non-collinear points A, B, C we say that π is the one and only one plane determined by A, B, C, We write the plane π as

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}\).

3. Axiom. If two distinct points lie in a plane then the line through the two points lies in the plane.

If A, B are two distinct points in a plane π, we say that \(\overleftrightarrow{A B}\) lies in the plane π.

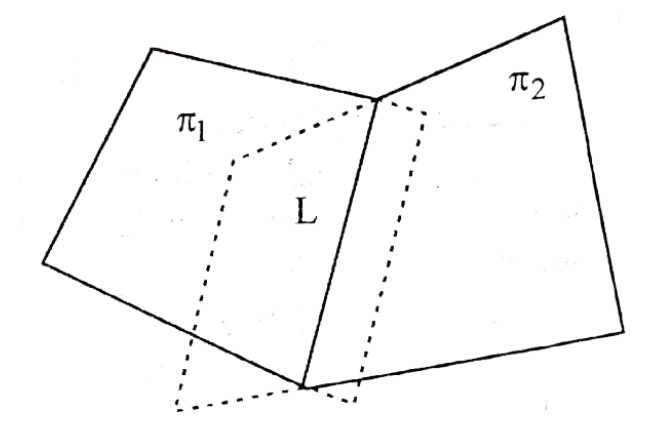

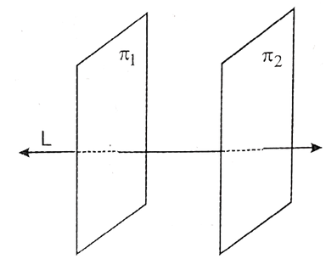

4. Axiom. If two planes intersect, they intersect in one and only one line π1,π2 are two intersecting planes intersecting in the line L.

5. Axiom. Every line consists of at least two points. Every plane consists of at least three non-collinear points. In space, there always exist at least four points. which are non-coplanar.

6. Axiom. Corresponding to any two points, there exists always a unique real number called the distance between the points.

If A, B are any two points, there exists a unique real number d (AB) or AB called the distance between the points A and B with the following properties (1) AB ≥ 0, (2) AB = 0 <=> A = B (3) AB = BA (4) AC + CB ≥ AB where C is any point.

7. Definition. If A, P, B are three collinear points such that AP+PB=Ab then we say that P lies between A and B on the line. We write A-P-B. The set of points P is called the line segment between A and B with endpoints A,B. we denote the line segment as AB.

It is to be understood that the meaning of AB is to be understood depending on the context.

If A-P-B and Ap=PB, then P is called the middle point of the line segment AB.

If A, B are different points, then AB ∪ {P/A-B-P} is called the ray from A through B and we write it as \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\)

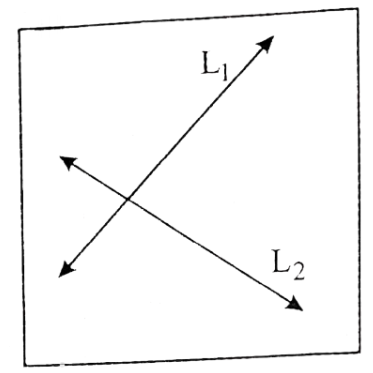

8. Definition. Two lines \(L_1, L_2\) in a plane π are said to intersect if \(L_1 \cap L_2 \neq \phi\) Now \(L_1, L_2\) are called intersecting lines.

9. Definition. Two lines \(L_1, L_2\) in a plane π are said to be parallel if either \(L_1, L_2\) are coincident \(\left(L_1=L_2\right) \text { or } L_1, L_2\) are not intersecting \(\left(L_1 \cap L_2 \neq \phi\right)\)

We write \(\mathrm{L}_1 \| \mathrm{L}_2\).

If A,B ∈ \(L_1\) and C,D ∈ \(L_2\) then write

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{A B} \| \overleftrightarrow{C D}\) or \(\mathrm{AB} \| \mathrm{CD}\).

If \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\)

are non-collinear, \(\overleftrightarrow{A B} \| \overleftrightarrow{C D}\)

and B, D lie on the same side of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\)

we say that \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \| \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\).

Also if \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\)are collinear we say that

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \| \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\).

If \(L_1, L_2\) are not parallel we write \(\mathrm{L}_1 / / \mathrm{L}_2\).

Definition Of A Plane In Euclidean Geometry

10. Axiom. To a given line, through a given point one and only one parallel line exists.

11. Theorem. Two distinct lines cannot intersect at more than one point.

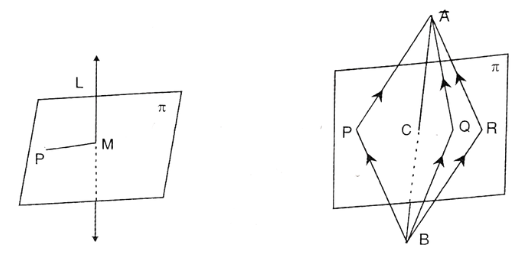

12. Theorem. If L is a line not in the plane π and intersecting π, then the line L intersects the plane π in one and only one point.

If the point is M in π, then M is called the foot of L in π.

13. Theorem. A plane containing a line and a point not on the line is unique.

If L ⊂ π and P ∉ L, then π is unique.

14. Theorem. Two intersecting lines determine a unique plane.

If \(\mathrm{L}_1 \text { and } \mathrm{L}_2\) are two intersecting lines \(\mathrm{L}_1 \text { and } \mathrm{L}_2\) determine a plane.

Axioms Of Planes In Euclidean Geometry Explained

15. Axiom. For every angle, there corresponds a unique number between 0 and π. This real number is called the measure of the angle.

The measure of an angle when measured by comparison with selected standard radial, the measure will be in radians. When the selected standard-a right angle is, the measure will be in degrees.

If θ is the angle between \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \text { and } \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\), we write θ = \(\angle(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}})=(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}})(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}})=\angle \mathrm{BAC}=\angle \mathrm{CAB}\) such that 0 ≤ θ ≤ π.

Also \((\overrightarrow{A B}, \overrightarrow{A B})=0\) and \((\overrightarrow{A B}, \overrightarrow{B A})=\pi\).

If \(\angle \mathrm{BAC}=\frac{\pi}{2}\),we say that\(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{BA}}\) is perpendicular to \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\)and we write

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{BA}} \perp \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\) or

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \perp \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}}\) or AB ⊥ Ac.

If \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}}\) are parallel to two lines

⇒ \(\mathrm{L}_1, \mathrm{~L}_2\) respectively, the angle between L1 and L2 is \((\overrightarrow{O P}, \overrightarrow{O Q})\)

or \(\pi-(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}})\).

Angle between parallel lines is 0 or π.

Here π is the measure of an angle and not a symbol used to denote a plane and the meaning of π is to be understood depending on context.

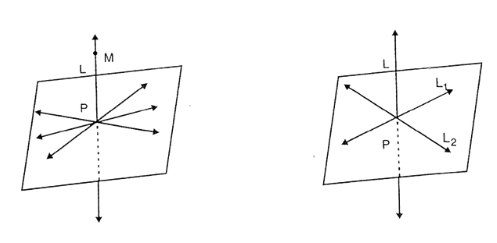

16. Definition. A line L cuts (or intersects) a plane π in a point P. If all the lines in π through P are perpendicular to L, then the line L is said to be perpendicular to the plane π. We write L ⊥ π or π ⊥ L. If M ∈ L, then we also write \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PM}} \perp \pi\) or PM ⊥ π.

17. Theorem. L1 and L2 are two lines intersecting at P. then L is perpendicular to the lines L1 and L2 at P is perpendicular to the plane determined by L1 and L2.

18. Theorem. P is a point and L is a line. Through P and perpendicular to L one and only plane (π) exists.

If L meets π in M, the PM ⊥ L.

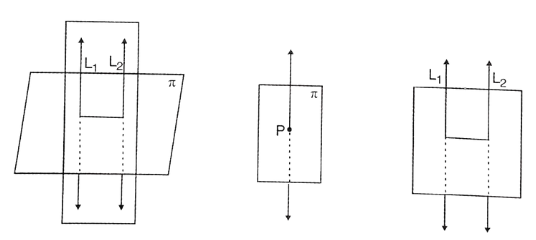

19. Theorem. The set of points so that each point is equidistant from two points A and B determine a unique plane (π) perpendicular to AB and intersecting AB at its middle point(C).

If P, Q , R… are points such that AP=PB, AQ=QB, AR=RB, …., then P, Q, R… are in the plane π where π ⊥ Ab at C

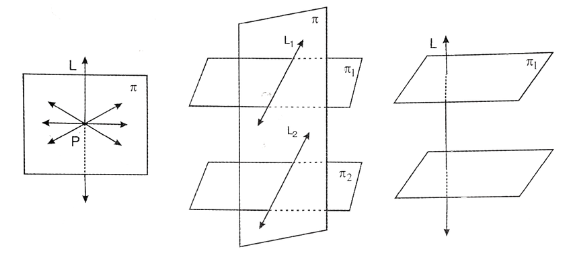

20. Theorem. If L1,L2 are two distinct lines perpendicular to the plane π, then L1 and L2 are parallel and coplanar.

21. Theorem. P is a point in the plane π. One and only one perpendicular line to π exists through P.

22. Theorem. L1,L2 are two parallel lines. If a plane is perpendicular to L1 then it is also perpendicular to L2.

23. Theorem. one and only one perpendicular line can be drawn to a plane from a point, not in the plane.

24. Theorem. L is a line and P is a point on L. If π is the plane perpendicular to L at P, then all the lines perpendicular to L through P lie in the plane π.

25. Definition. L is a line and π is a plane. If no point of L is in π(L∩π=ϕ) or if L is in π, then L is said to be parallel to π and we write L ∥ π.

26. Definition. π1, π2 are two planes which are either coincident (π1=π2) or parallel (π1 ∩ π2 = ϕ). Then π1,π2 are said to be parallel and we write π1 ∥ π2.

27. Theorem. π1,π2 are two distinct parallel planes. If a plane π cuts π1 in a line L1 and π2 in a line L2, then L1∥ L2.

28. Theorem. If L is a line perpendicular to the plane π1, then L is perpendicular to the planes parallel to π1.

29. If π1, π2 are two planes perpendicular to the lines L, then π1 ∥ π2.

30. Theorem. If L1 is a line parallel to any line in a plane π then L1 ∥ π.

31. Theorem. L1 is a line parallel to the plane π1. π2 is a plane containing L1 and intersecting π1 in L2. Then L1 ∥ L2.

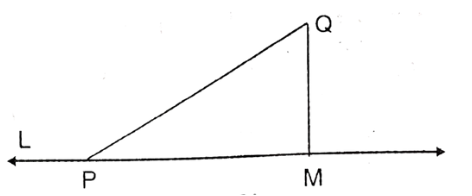

32. Theorem. L is a line in a plane π. R is a point on L. Also Q is a point in π, but not on L. Further, P is a point not in π. Then

1) QR ⊥ L and PR ⊥ L ⇒ PQ ⊥ π

2) PR ⊥ L and PQ ⊥ π ⇒ QR ⊥ L

3) PQ ⊥ π and QR ⊥ L ⇒ PR ⊥ L

This is called the theorem of three perpendiculars.

33. Theorem. Two parallel planes π1, π2 always make equal intercepts or lines perpendicular to π1,π2.

Definition. L is perpendicular to π1, π2. The intercept on L by π1,π2 is called the distance between π1 and π2.

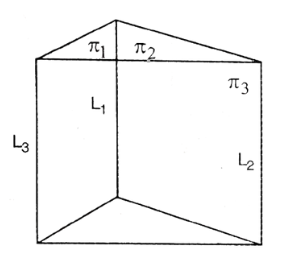

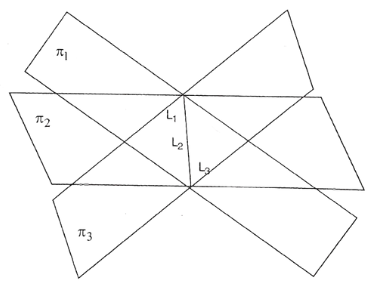

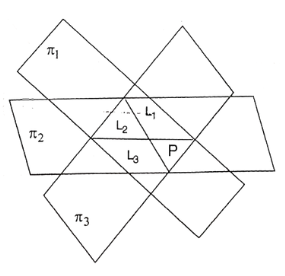

34. Definition. If L1, L2, L3 are three lines such that L1 ∩ L2 ∩ L3 = P, then the lines L1, L2 and L3 are said to be concurrent.

35. Theorem. If L1 ∥ L2, L2 ∥ L3, then L1 ∥ L3.

We say that L1, L2, L3 are parallel and we write L1 ∥ L2 ∥ L3.

Examples Of Planes In 2d And 3d Euclidean Geometry

36. Theorem. π1, π2, π3 are three distinct planes so that no two of which are parallel. The three lines of their intersection are either parallel or concurrent.

37. Projections. Here projection will mean orthogonal projection only.

1. Definition. P is a point and L is a line. P ∉ L. If M is the foot of the perpendicular from P on L, then M is called the projection of P in L.

2. Definition. P is a point and π is a plane not containing P. If the perpendicular from P to π meets π in the point M, then M is called the projection of P in π.

3. Definition. P, Q are two points and L is a line, P ∈ L and Q ∉ L. If M is the projection of Q and L, the PM is called the projection of PQ in L.

4. Definition. P, Q are two points and L is a line. P, Q ∉ L. If M,N are the respective projections of P, Q in L, then the line segment MN is called the projection of the line segment PQ in L.

5. Theorem. π is a plane and L is a line not in π. If perpendicular are drawn from every point on L to π, then all the projections in π are either collinear (when L is not perpendicular to π) or coincident in a point (when L ⊥ π).

38. Some Useful results

1. L is a line and P is a point on it. The perpendicular to L at P are coplanar.

2. The planes perpendicular to a line are all parallel.

3. L is a line perpendicular to a plane π. All the planes through L are perpendicular to π.

4. L1, L2 are a pair of intersecting lines. L3, L4 are a second pair of intersecting lines so that L3 ∥ L1 and L4 ∥ L2.

Then

- the angle between the first pair=the angle between the second pair.

- the plane determined by the first pair is parallel to the plane determined by the second pair.

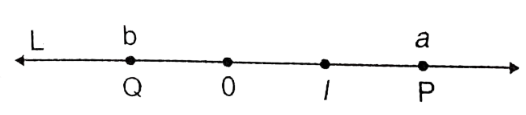

39. Definition. L is a line and R is the set of real numbers. \(f: L \rightarrow R\) is a one-one mapping. If A,B ∈ L such that \(|A, B|=|f(A)-f(B)|\), then f is called a coordinate system for L.

The real number x(=f(p)) is called the coordinate of P w.r.t the coordinate system f on the line L and we write it as p(x).

In this context, L is called the coordinate line. The set p(x) is called the geometric figure on L.

Axiom. Every line has a coordinate system.

A coordinate system on the line L depends on arbitrarily chosen points O and I on L such that

- O, called the origin, corresponds to the number of the O, and

- I, called the unit point, to correspond to the number 1.

Clearly, we can have infinitely many coordinate systems defined on L.

Then for every real number x and for each point P on L one-to-one correspondence exists with the following properties and notation,p(x) denotes the point p with coordinate x’

p(a),Q(b) ∈ L ⇒

- p(a) = 0 <=> p=0,

- p(a) lies to the right of O is a>0, and Q(b) lies to the left of O if b <0,

- Between P and Q, distance = PQ=|b-a| and directed distance = b-a,

- p(a) lies to the right of Q(b) if a > b,

- Q(b) lies to the left of p(a) if b < a,

- p(A) coincides with Q(b) i.e., P=Q if a=b.

40. Definition. A(a)., P(x), B(b) are points on the coordinate line L. Then

- A-P-B ⇒ is said to divide the line segment AB internally in the ratio (x-a):(b-x) and x-a,b-x are positive.

- P-A-B or A-B-P ⇒ is said to divide the line segment AB externally in the ratio (x-a,(b-x) are of opposite signs. we write (P;A,B)=(x-a):(b-x). It is +ve or -ve according as P divides AB internally or externally.

IF (P;A,B) = m:n, then (x-a):(b-x) = m:n ⇒ n(x-a)=m(b-x)

41. Theorem. In a given ratio a line segment is divided at one an only the point.

42. Skew lines.

Definition. Any two non-parallel and non-intersecting lines are called skew lines.

Since any two lines in a plane must be either parallel or intersecting, skew lines are non-coplanar. Conversely, any two non-coplanar lines are skew lines.

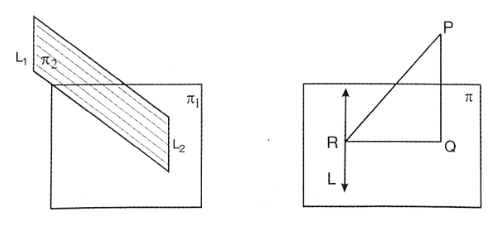

43. Theorem. L1,L2 are two skew lines. Then there exist one and only one plane π through one of the lines and parallel to the second.

44. Theorem. If \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}}\) is the projection of a line L in a plane π, then \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}}\), L are coplanar.

If L ∥ π, then L ∥ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}}\).

45. Theorem. If L1,L2 are two skew lines, then there exists one and only one line that intersects L1,L2 and is perpendicular to L1,L2.

Properties and axioms of planes in mathematics

46. Definition. L is a line and π1 is a plane not containing L. If L is not parallel to π1, then the angle between L and π1 (written as (L, π1)) is the angle between L and \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}}\), where \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}}\) is the projection of L in π1.

We write \(\left(\mathrm{L},\pi_1\right)=(\mathrm{L}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}})\).

We can have (L,π1)= \(\frac{\pi}{2} \pm \theta\)

where θ is the acute angle between L and a normal to π1.