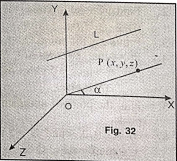

Coordinates Of A Point In Space

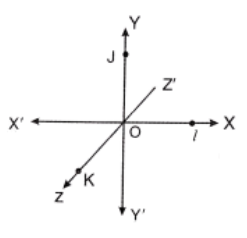

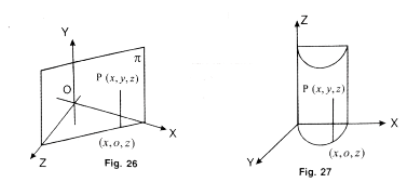

Let O be any point in space S. Let \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}, \overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\) be two perpendicular lines through O. Let the plane determined by the lines be \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{XOY}}\).

Through O and perpendicular to the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{XOY}}\) let \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) be a line.

Imagine the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{XOY}}\) as the plane of the paper and the perpendicular \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) is to be visualized as perpendicular lines through O.

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) may be regarded as vertical and \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}, \overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\) as horizontal. ⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}, \overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}, \overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) are three non-coplaner mutual perpendicular lines through O.

The lines \(\overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) determine the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{YOZ}}\) and the lines \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}, \overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\) determine the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ZOX}}\).

Also \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{XOY}},\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{YOZ}},\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ZOX}}\) are three mutually perpendicular planes through O.

On \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\) take O as the origin, I as the unit point;

On \(\overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\) take O as the origin, J as the unit point and

On \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) take O as the origin, K as the unit point such that \(\overline{\mathrm{OI}}=\overline{\mathrm{OJ}}=\overline{\mathrm{OK}}\)

The coordinate of a point on \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\) is called its x-coordinate, the coordinate of a point on \(\overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\) is called its y-coordinate and the coordinate of a point on \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) is called its z-coordinate.

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{XOY}}\)(XY plane), \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{YOZ}}\)(YZ plane),\(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ZOX}}\)(ZX plane) are called the rectangular coordinate planes.\(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\)(x-axis), \(\overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\)(y-axis),\(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\)(z-axis) are called the rectangular coordinate axes.

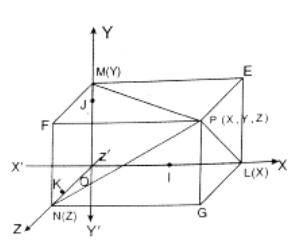

Such an assigned system of axes is called the frame of reference or coordinate frame (denoted by OXYZ) so that the coordinates of a point change with the change in the frame of reference. P is any point in space.

L, M, and N are respectively the projections on the coordinates axes. Let the X coordinate of L be x, Y coordinate of M be y and Z coordinate of N be z. The numbers x, y, z taken in this order are called the rectangular coordinates of P. We write p = (x, y, z). Thus point P is associated with an ordered trias of real numbers.

Let (x, y, z) be an ordered triad. Take the point L of co-ordinate x on \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\), the point M of coordinate y on \(\overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\) and the point N of coordinate z on \(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\).

Through the points L, M, N draw planes π1, π2, π3 perpendicular to the coordinate axes \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\),\(\overleftrightarrow{Y^{\prime} Y}\),\(\overleftrightarrow{Z^{\prime} Z}\) respectively. The three mutually perpendicular planes π1, π2, π3 intersect at a unique point P.

Since P ∈ π1, the projection of P on \(\overleftrightarrow{X^{\prime} X}\) is L and hence the x-coordinate of p is equal to L. Similarly the y-coordinate of p is equal to the y-coordinate of M and the z-coordinate of p is equal to the z-coordinate of N.

The coordinates of P are x, y, and z in that order. Thus for the ordered triad (x, y, z), we have a unique point P in space.

Hence a one-to-one correspondence is established between the set of points in space and the set of ordered traids of real numbers. This space is called 3D space or R3 space.

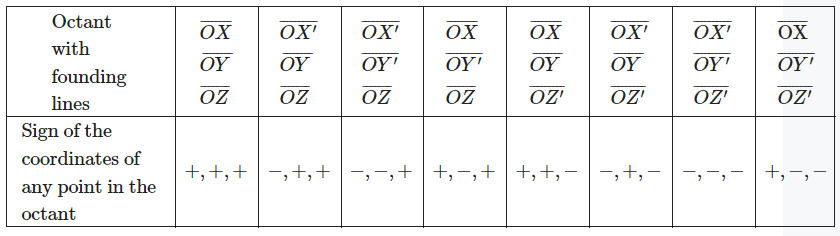

The three coordinate planes divide the space into eight compartments, each of which is called an octant.

Clearly, the three planes through P are respectively parallel to the coordinates planes and the six planes form a rectangular parallelopiped. The three pairs of rectangular faces are

Coordinates Definition And Solved Exercise Problems

PFNG, EMOL; PGLE, FNOM; PEMF, GLON

We have

(1) For any point on the X-axis, y = 0 and z = 0.

For any point on the Y-axis, x = 0 and z = 0.

For any point on the Z-axis, x = 0 and y = 0.

(2) For any point on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{XOY}}\) plane z = 0.

For any point on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{YOZ}}\) plane x = 0.

For any point on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ZOX}}\) plane y = 0.

(3) Origin O = (0, 0, 0)

(4) |x| = OL = ME = NG = FP = Distance of p from YZ plane,

|y| = OM = LE = NF = GP = Distance of p fron ZX plane,

|z| = ON = LG = MF = EP = Distance of p from XY plane.

(5) PL, PM, and PN are respectively perpendicular to X axis, Y axis, Z axis.

(6) Distance of p from the X-axis = PL = \(\sqrt{\left(\mathrm{LE}^2+\mathrm{EP}^2\right)}=\sqrt{\left(y^2+z^2\right)}\)

Distance of P from the Y-axis = PM = \(\sqrt{\left[\mathrm{EP}^2+\mathrm{ME}^2\right]}=\sqrt{\left(z^2+x^2\right)}\), (∵ (\(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{EP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{EM}})=90^{\circ}\))

Distance of P from the Z-axis = PN = \(\sqrt{\left[\mathrm{NF}^2+\mathrm{FP}^2\right]}=\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2\right)}\), (∵ (\(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{FP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{FN}})=90^{\circ}\))

(7) \(\mathrm{OP}=\sqrt{\left[\mathrm{OL}^2+\mathrm{PL}^2\right]}=\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}\) (∵ (\(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{LO}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{LP}})=90^{\circ}\))

(8) The projection of p(x, y, z) on the coordinates axes are L, M, N where L = (x, 0, 0), M = (0, y, 0), and N = (0, 0, z).

The projections of p(x, y, z) on the coordinate planes (YZ, ZX, XY) are F, G, E. where F = (0, y, 0), G = (x, 0 z), E = (x, y, 0).

(9) \(\begin{array}{ll}

\mathrm{X} \text { axis }=\{\mathrm{P}(x, y, z) / y=0, z=0\}, & \mathrm{YZ} \text { plane }=\{\mathrm{P}(x, y, z) / x=0\}, \\

\mathrm{Y} \text { axis }=\{\mathrm{P}(x, y, z) / x=0, z=0\}, & \mathrm{XY} \text { plane }=\{\mathrm{P}(x, y, z) / z=0\}, \\

\text { Z axis }=\{\mathrm{P}(x, y, z) / x=0, y=0\}, & \text { ZX plane }=\{\mathrm{P}(x, y, z) / y=0\} .

\end{array}\)

Coordinates Interpretation Of Equations

Definition. A locus is the set of points and only those points satisfying a given condition.

Definition. F is a function from R3 into R.

Then the locus S = {(x, y, z)|F(x, y, z) = 0} is called the surface represented by the equation F(x, y, z) = 0.

F(x, y, z) = 0 is called an equation to the surface S.

Definition. If F is a polynomial (not a zero polynomial) in x, y, z then the locus (surface) represented by F(x, y, z) = 0 is called an algebraic surface.

Consider.

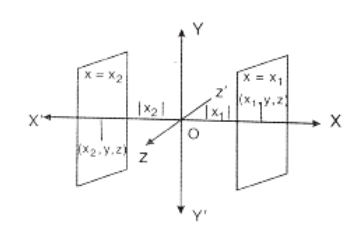

(1) F(x)=0 where F(x) is a polynomial. So F(x) = 0 has a finite number of real roots. Let x1,x2,…..,xn be the real roots. The locus (surface) \(\pi_1=\left\{(x, y, z) / x=x_1\right\}\) is a plane parallel to YZ plane since every point in π1 has its x coordinate x1

Similarly, the locus (surface) of each of the equations x = x2,….,x = xn is a plane parallel to YZ plane. Thus the locus of the equation F(x) = 0 is a system of planes parallel to the YZ plane.

Similarly, F(y) = 0 and F(z) = 0 can be interpreted.

(2) F(x,z) = 0 where is a first degree polynomial in x, z (say, 3x – 5z = 15). This is a line in ZX plane. The locus (surface) π = {(x, y, z)|F(x, z) = 0} is a plane parallel to the Y axis since every point P(x, y, z) in π has a point on the line with the same x and z coordinates.

Similarly, F(x, y) = 0 where F(x, y) is a first-degree polynomial is the equation of a plane parallel to Z axis and F(y, z) = 0 where F(y, z) is a first-degree polynomial is the equation of a plane parallel to the x-axis.

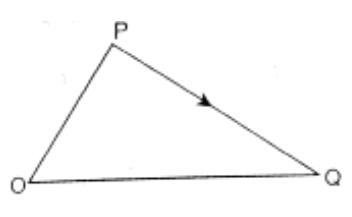

(3) The curve F(x, z) = 0 is of second degree in the ZX plane in the two-dimensional Cartesian system.

Let Q(x, 0, z) be any point on F(x, z) = 0. Then the point P(x, y, z) where y ∈ R satisfies the equation F(x, z) = 0. \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) is a line parallel to Y-axis.

∴ For all Q on F(x, z) = 0, we have a set of lines parallel to the y-axis.

Thus the locus of the equation F(x, z) = 0 in 3D space is a system of lines parallel to the y-axis and the locus is a surface called a cylinder. Each of the lines is called a generator of the cylinder.

Similarly, F(x, z) = 0 and F(z, x) = 0 can be interpreted.

A surface generated by a line so that it keeps parallel to a fixed line and intersects a fixed curve in a plane is called a cylindrical surface or a cylinder. In accordance with this definition, a plane in (1) , or (2) is a special case of a cylinder.

Thus the locus (surface) or an equation in two variables is a cylinder with generators parallel to the axis of the missing variable.

(4) If F(x, y, z) = 0 and Φ (x, y, z) = 0 separately represent two surfaces then the points satisfying both equations lie on the curve of the intersection of the two surfaces.

The study of 3D geometry is made through vector methods wherever feasible. The students are already familiar with a detailed study of the geometrical concept of vectors in Vector Algebra. By expressing the equivalence of a vector to an ordered triad, we recapitulate the necessary ideas of Vector Algebra in the ensuing articles.

If felt convenient, methods using concepts of Vector Algebra may be used by students while proving theorems or solving problems.

Coordinates Vector

Let OXYZ be a frame of reference and \(\bar{i}, \bar{j}, \bar{k}\) be a unit orthogonal vector ordered triad (along \(\overline{\mathrm{OX}}, \overline{\mathrm{OY}}, \overline{\mathrm{OZ}}\)) in the right-handed system.

Let P(x, y, z) be any point in space and be determined by its position vector \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}\). Then we can have \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=x \bar{i}+y \bar{j}+z \bar{k}\) for unique scalars x, y, z.

In view of this, let the point (x, y, z) be associated with a unique vector \(x \bar{i}+y \bar{j}+z \bar{k}\) and the vector \(x \bar{i}+y \bar{j}+z \bar{k}\) be associated with a unique point (x, y, z).

Thus in R3-space, a one-to-one correspondence is established between the set of points and the set of position vectors. Hence we write (x, y, z) = \(x \bar{i}+y \bar{j}+z \bar{k}\)

The coordinate of any point P are the rectangular components of its position vector \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}\).

Any point on x-axis = (x, 0, 0) = \(x \bar{i}\), any point on the y-axis (0, y, 0) = \(y \bar{j}\) and any point on the z-axis (0, 0, z) = \(z \bar{k}\)

If \(\bar{a}\) istaken to represent the position vector of the point A(x, y, z), then

A \(=\bar{a}=x_1 \bar{i}+y_1 \bar{j}+z_1 \bar{k}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\)

Theorems On Plane Coordinates With Examples

Note. \(\overline{\mathrm{O}}=0 \bar{i}+0 \bar{j}+0 \bar{k}=(0,0,0)\).

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{P}}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \overline{\mathrm{Q}}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) are any two points. Then

(1) \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}+\overline{\mathrm{OQ}}=\left(x_1 \bar{i}+y_1 \bar{j}+z_1 \bar{k}\right)+\left(x_2 \bar{i}+y_2 \bar{j}+z_2 \bar{k}\right)\)

= \(\left(x_1+x_2\right) \bar{i}+\left(y_1+y_2\right) \bar{j}+\left(z_1+z_2\right) \bar{k}\)

= \(\left(x_1+x_2, y_1+y_2, z_1+z_2\right)\)

(2) \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}-\overline{\mathrm{OQ}}=\left(x_1-x_2, y_1-y_2, z_1-z_2\right)\).

(3) \(\lambda \overline{\mathrm{OP}}=(\lambda(x \bar{i}+y \bar{j}+z \bar{k})=\lambda x \bar{i}+\lambda y \bar{j}+\lambda z \bar{k}=(\lambda x, \lambda y, \lambda z)\) where λ is a real number.

(4) \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}=\overline{\mathrm{PO}}+\overline{\mathrm{OQ}}=\overline{\mathrm{OQ}}-\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)\)

Definition. If \(\bar{a}=\overline{\mathrm{AB}}, \bar{b}=\overline{\mathrm{CD}}\) such that A, B, C, D are collinear or \(\overleftrightarrow{A B} \| \overleftrightarrow{C D}\), then \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) are said to be parallel or collinear.

Sometimes we write \(\bar{a} \| \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}} \text { or } \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \| \vec{b}\).

If \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) are not parallel or not collinear, then \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) are called non-parallel or non-collinear vectors.

P \(=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \mathrm{Q}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) are any two points. O, P, and Q are collinear

<=> \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\lambda \overline{\mathrm{OQ}}, \lambda\) is a real number

<=> \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)=\lambda\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \Leftrightarrow x_1: x_2=y_1: y_2: z_2=\lambda: 1\)

Coordinates Length Or Magnitude Of A Vector

Any point \(\overline{\mathrm{P}}=(x, y, z) \text { and } \overline{\mathrm{OP}}=(x, y, z)\). The length or magnitude or norm or modulus of the vector \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=|\overline{\mathrm{OP}}|=\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\sqrt{\left(x^2, y^2, z^2\right)}\)

Theorem 1. Distance between two points (x1, y1, z1) and (x2, y2, z2) is \(\sqrt{\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2\right]}\).

Proof. Let A = (x1, y1, z1), B = (x2, y2, z2).

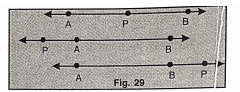

Complete the parallelogram OABP so that OP ∥ AB and OP = AB.

∴ \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\overline{\mathrm{AB}}\)

∴\(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)\)

⇒ \(|\overline{O P}|=O P=\sqrt{\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2\right]}\)

∴ \(|\overline{\mathrm{OP}}|=\mathrm{OP}=\sqrt{\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2\right]}\)

∴ \(|\overline{\mathrm{AB}}|=\mathrm{AB}=\sqrt{\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2\right]}\)

∴ Distance between points A = (x1, y1, z1), B = (x2, y2, z2)

= \(\mathrm{AB}=\sqrt{\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2\right]}\)

If \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) are two vectors, then there exists a unique vector \(\bar{c}\) such that \(\bar{c}+\bar{b}=\bar{a}\) i.e., \(\bar{a}\) = (x1, y1, z1), \(\bar{b}\) = (x2, y2, z2), \(\bar{c}\) = (x, y, z) then (x, y, z) + (x2, y2, z2) = (x1, y1, z1) ⇒ (x1, y1, z1) = (x1 – x2, y1 – y2, z1 – z2)

Coordinates Unit Vector

If A, B, and A ≠ B, are points, then \(\frac{\overline{\mathrm{AB}}}{|\overline{\mathrm{AB}}|}\) is the unit vector along \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) in the direction from A to B.

If A = (x1, y1, z1), B = (x2, y2, z2) then the unit vector along \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) in the direction from A to B = \(\frac{\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)}{\sqrt{\left[\left(x_2-x_1\right)^2+\left(y_2-y_1\right)^2+\left(z_2-z_1\right)^2\right]}}\)

If \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}}=\bar{a}, \overline{\mathrm{OB}}=\bar{b}\) are two non-collinear vectors, \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}\) determine a unique plane denoted by \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AOB}}\) and we say that it is the plane containing \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\).

Coordinates Coplanar, Non-Coplanar Vectors

Let \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) be two non-collinear vectors and \(\bar{c}\) be a vector. Let O be the origin and A, B, C be three points such that \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}}=\bar{a}, \overline{\mathrm{OB}}=\bar{b}, \overline{\mathrm{OC}}=\bar{c}\). Since \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}}, \overline{\mathrm{OB}}\) are non-collinear, they determine the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AOB}}\).

If C ∈ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AOB}}\), then \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}}, \overline{\mathrm{OB}}, \overline{\mathrm{OC}}\) are said to be coplanar and if \(\mathrm{C} \notin \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AOB}}\), then \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}}, \overline{\mathrm{OB}}, \overline{\mathrm{OC}}\) are said to be non-coplanar. \(\bar{i}, \bar{j}, \bar{k}\) are non-coplanar.

Coordinates Angle Between Vectors

If \(\bar{a}=\overline{\mathrm{OA}}, \bar{b}=\overline{\mathrm{OB}}\), then the angle between the vectors \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) [written as (\(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\))] is (\(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}\)) such that \(0^{\circ} \leq(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}) \leq 180^{\circ}\).

We write \(0^{\circ} \leq(\bar{a}, \bar{b}) \leq 180^{\circ}\). We have \((\bar{a},-\bar{b})=(-\bar{a}, \bar{b})=(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{BO}})=(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AO}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}})\)

If \((\bar{a}, \bar{b})=90^{\circ}\), then we write \(\bar{a} \perp \bar{b} \text { or } \overline{\mathrm{OA}} \perp b \text { or } \bar{a} \perp \overline{\mathrm{OB}} \text { or } \overline{\mathrm{OA}} \perp \overline{\mathrm{OB}}\).

We take that the null vector is perpendicular to every vector.

If \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are non-coplanar and \(\bar{r}\) is any vector, then there exist unique real numbers x, y, z such that \(\bar{r}=x \bar{a}+y \bar{b}+z \bar{c}\). \(\bar{r}\) is said to be a linear combination of \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\).

Since \(\bar{i}, \bar{j}, \bar{k}\) are non-coplanar \(\bar{r}=x \bar{a}+y \bar{b}+z \bar{c}\). \(\bar{r}\), for unique scalars x, y, z.

⇒ \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are non-coplanar.

(1) \(x_1 \bar{a}+y_1 \bar{b}+z_1 \bar{c}=x_2 \bar{a}+y_2 \bar{b}+z_2 \bar{c} \Rightarrow x_1=x_2, y_1=y_2, z_1=z_2\)

(2) \(x_1 \bar{a}+y_1 \bar{b}+z_1 \bar{c}=0 \Rightarrow x_1=0, y_1=0, z_1=0\).

Solved Problems On Interpretation Of Equations In Plane Coordinates

Definition. A, B are two points. If λ1, λ2,(λ1 + λ2 ≠ 0) are two real numbers such that P ∈ AB and \(\lambda_2 \overline{\mathrm{AP}}=\lambda_1 \overline{\mathrm{PB}}\), we say that P divides AB in the ratio λ1 : λ2.

λ1 : λ2 and λ1, λ2 < 0, P-A-B or A-B-P i.e., P is said to divide the line segment AB externally in the ratio λ1:λ2.

If \(\mathrm{A}=\bar{a}, \mathrm{~B}=\bar{b} \text { and }(\mathrm{P} ; \mathrm{A}, \mathrm{B})=\lambda_1: \lambda_2 \text { then } \overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\frac{\lambda_1 \bar{a}+\lambda_2 \bar{b}}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\left(\lambda_1+\lambda_2 \neq 0\right)\)

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{A}}, \overline{\mathrm{B}}, \overline{\mathrm{C}}\) are three points whose position vectors are \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) respectively. \(\mathrm{A}(\bar{a}), \mathrm{B}(\bar{b}), \mathrm{C}(\bar{c})\) are collinear <=> \(\overline{l a}+m \bar{b}+n \bar{c}=0, l+m+n=0,(l, m, n) \neq(0,0,0)\)

Coordinates Dot Product Or Direct Product Or Scalar Product Or Inner Product.

Definition. If \(\vec{a}, \vec{b}\) are two non-zero vectors, then \(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}=|\bar{a}||\bar{b}| \cos (\bar{a}, \bar{b})\) and if one of \(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}\) is zero then \(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}=0\).

Now \(\bar{i} \cdot \bar{i}=1, \bar{j} \cdot \bar{j}=1, \bar{k} \cdot \bar{k}=1, \bar{i} \cdot \bar{j}=0, \bar{i} \cdot \bar{k}=0, \bar{j} \cdot \bar{k}=0\).

If \(\bar{a}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \bar{b}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \text {, then } \bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \cdot\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\)

= \(\left(x_1 \bar{i}, y_1 \bar{j}, z_1 \bar{k}\right) \cdot\left(x_2 \bar{i}, y_2 \bar{j}, z_2 \bar{k}\right)=x_1 x_2+y_1 y_2+z_1 z_2\)

Also we have (x1, y1, z1).(x2, y2, z2) = (x2, y2, z2).(x1, y1, z1)

Also if \(|\bar{a}|=\bar{a} \text {, then } \bar{a}^2=\bar{a}^2=\bar{a} \cdot \bar{a}=x_1^2+y_1^2+z_1^2\)

If \(\bar{a}\) is a unit vector, then \(\bar{a}^2=|\bar{a}|^2=1\).

If \(\mathrm{P}=\bar{a}=\left(a_1, b_1, c_1\right), \mathrm{Q}=\bar{b}=\left(a_2, b_2, c_2\right), \mathrm{P} \neq \mathrm{Q} \neq \mathrm{O} \text { and }(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}})=(\bar{a}, \bar{b})=\theta\)

then \(\cos \theta=\frac{\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}}{|\bar{a}||\bar{b}|}=\frac{a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)} \cdot \sqrt{\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)}}\)

⇒ \(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}\) are parallel vectors <=> \(\bar{a}=\lambda \bar{b}\)

⇒ \(\left(a_1, b_1, c_1\right)=\lambda\left(a_2, b_2, c_2\right) \Leftrightarrow a_1=\lambda a_2, b_1=\lambda b_2, c_1=\lambda c_2\)

⇒ \(a_1: b_1: c_1=a_2: b_2: c_2 \text { or } a_1: a_2=b_1: b_2=c_1: c_2\)

⇒ \(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}\) are perpendicular vectors <=> \(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}=0 \Leftrightarrow a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2=0\)

Projection of \(\bar{b} \text { on } \bar{a}(\neq 0) \text { is } \bar{b} \cdot \frac{\bar{a}}{|\bar{a}|}=\frac{\bar{b} \cdot \bar{a}}{|\bar{a}|}=\bar{b} \cdot \bar{e}\) where \(\bar{e}\) is the unit vector in the direction of \(\bar{a}\).

⇒ \(\bar{a} \cdot(\bar{b}+\bar{c})=\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}+\bar{a} \cdot \bar{c}, \bar{a} \cdot(\bar{b}-\bar{c})=\bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}-\bar{a} \cdot \bar{c}\)

⇒ \((\bar{a}-\bar{b})^2=(\bar{a}-\bar{b}) \cdot(\bar{a}-\bar{b})=\bar{a}^2-2 \bar{a} \cdot \bar{b}+\bar{b}^2\)

Coordinates Cross Product Skew Product Or Vector Product

If \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) are two non-zero or non-parallel vectors, then \((\bar{a} \times \bar{b})=|\bar{a}||\bar{b}| \sin (\bar{a}, \bar{b}) \bar{n}\) where \(\bar{n}\) is a unit vector perpendicular to the plane containing \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) so that \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{n}\) form a right handed system and if at least one of \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}\) is a null vector or \(\bar{a} \| \bar{b}\), then \((\bar{a} \times \bar{b})=0\).

We find that \(\bar{a} \times \bar{b}=-\bar{b} \times \bar{a} \text { and }|\bar{a} \times \bar{b}|=|\bar{a}||\bar{b}||\sin (\bar{a}, \bar{b})|\)

We find that \(\bar{a} \times \bar{b}=-\bar{b} \times \bar{a} \text { and }|\bar{a} \times \bar{b}|=|\bar{a}||\bar{b}||\sin (\bar{a}, \bar{b})|\)

Now \(\bar{i} \times \bar{i}=0, \bar{j} \times \bar{j}=0, \bar{k} \times \bar{k}=0, \bar{i} \times \bar{j}=\bar{k}, \bar{i} \times \bar{k}=-\bar{j}, \bar{j} \times \bar{k}=\bar{i}, \bar{k} \times \bar{j}=-\bar{i}\)

⇒ \(\bar{j} \times \bar{i}=\bar{k}, \bar{k} \times \bar{i} \times \bar{j} .\)

If \(\bar{a}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \bar{b}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\), then

\(\bar{a} \times \bar{b}=\left(x_{\bar{b}}, y_1, z_1\right) \times\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)=\left(x_1 \bar{i}+y_1 \bar{j}+z_1 \bar{k}\right) \times\left(x_2 \bar{i}, y_2 \bar{j}, z_2 \bar{k}\right)\)= \(x_1 y_2 \bar{k}-x_1 z_2 \bar{j}-x_2 y_1 \bar{k}+y_1 z_2 \bar{i}+z_1 x_2 \bar{j}-z_1 y_2 \bar{i}\)

= \(\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1\right) \bar{i}-\left(x_1 z_2-x_2 z_1\right) \bar{j}+\left(x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right) \bar{k}\)

= \(\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1, x_2 z_1-x_1 z_2, x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right)=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\bar{i} & \bar{j} & \bar{k} \\

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2

\end{array}\right|\)

i.e. \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \times\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)=\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1, x_2 z_1-x_1 z_2, x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right)\)

⇒ \(\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \times\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)=-\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1, x_2 z_1-x_1 z_2, x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right)\)

and \(\left|\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \times\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\right|=\sqrt{\left[\sum\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1\right)^2\right]}\)

If \(\mathrm{P}=\bar{a}=\left(a_1, b_1, c_1\right), \mathrm{Q}=\bar{b}=\left(a_2, b_2, c_2\right)=(\mathrm{P} \neq \mathrm{Q} \neq \mathrm{O})\)

and \((\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}})=(\vec{a}, \bar{b})=\theta\), then

⇒ \(\sin \theta=\frac{|\bar{a} \times \bar{b}|}{|\bar{a}||\bar{b}|}=\frac{\left|\left(b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1, c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1, a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1\right)\right|}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)} \cdot \sqrt{\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)}}\)

If \(\overline{\mathrm{ABC}}\) is a triangle, then the area of \(\Delta \overline{\mathrm{ABC}}=\frac{1}{2}|\overline{\mathrm{AB}} \times \overline{\mathrm{AC}}|\) square units.

Also \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}} \times \overline{\mathrm{AC}}\) is a vector perpendicular to the plane of \(\triangle \overline{\mathrm{ABC}}\).

Area of \(\triangle \overline{\mathrm{ABC}}\) = 0 ⇔ A, B, C are collinear.

A, B, C, and D are coplanar points. If ABCD is a parallelogram then the area of the parallelogram = \(|\overline{\mathrm{AB}} \times \overline{\mathrm{AD}}| \text { or } \frac{1}{2}|\overline{\mathrm{AC}} \times \overline{\mathrm{BD}}|\) square units.

If ABCD is a quadrilateral, then the area of the quadrilateral = \(\frac{1}{2}|\overline{\mathrm{AC}} \times \overline{\mathrm{BD}}|\) square units.

⇒ \(\bar{a}=\left(a_1, a_2, a_3\right), \bar{b}=\left(b_1, b_2, b_3\right), \bar{c}=\left(c_1, c_2, c_3\right)\)

⇒ \(\bar{a} \times \bar{b}=\left(a_2 b_3-a_3 b_2, a_3 b_1-a_1 b_3, a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1\right)\)

∴ \([\bar{a} \bar{b} \bar{c}]=(\bar{a} \times \bar{b}) \cdot \bar{c}\)

= \(\left(a_2 b_3-a_3 b_2, a_3 b_1-a_1 b_3, a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1\right) \cdot\left(c_1, c_2, c_3\right)\)

= \(\left(a_2 b_3 c_1-a_3 b_1 c_1+a_3 b_1 c_2-a_1 b_3 c_2+a_1 b_2 c_3-a_2 b_1 c_3\right)=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

a_1 & a_2 & a_3 \\

b_1 & b_2 & b_3 \\

c_1 & c_2 & c_3

\end{array}\right|\)

i.e. \([\bar{a} \bar{b} \bar{c}]=\left[\left(a_1, a_2, a_3\right),\left(b_1, b_2, b_3\right),\left(c_1, c_2, c_3\right)\right]=\left|\begin{array}{lll}

a_1 & a_2 & a_3 \\

b_1 & b_2 & b_3 \\

c_1 & c_2 & c_3

\end{array}\right|\)

⇒ \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are three non-coplanar vectors. If V is the volume of the parallelopiped with adjacent sides \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) then \( \bar{V}=|[\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}]|\) cubic units.

If V is the volume of the tetrahedron with adjacent sides \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) then \(\overline{\mathrm{V}}=\frac{1}{6}|[\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}]|\) cubic units. Also if any two of \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are parallel, \(\lceil\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\rceil=0\)

One of \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) is \(0 \Rightarrow[\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}]=0\) . Also if any two \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are parallel, \([\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}]=0\).

⇒ \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are three non-zero, non-parallel vectors. \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are parallel, <=> \([\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}]=0\).

If \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\) are three non-coplanar vectors, then \([\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}]^2=\left|\begin{array}{lll}

\bar{a} \cdot \bar{a} & \bar{a} \cdot \bar{b} & \bar{a} \cdot \bar{c} \\

\bar{b} \cdot \bar{a} & \bar{b} \cdot \bar{b} & \bar{b} \cdot \bar{c} \\

\bar{c} \cdot \bar{a} & \bar{c} \cdot \bar{b} & \bar{c} \cdot \bar{c}

\end{array}\right|\)

A, B are two distinct points. Distance of P from \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}=\frac{|\overline{\mathrm{AP}} \times \overline{\mathrm{AB}}|}{|\overline{\mathrm{AB}}|}\)

A, B, and C are distinct points.

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}, \overline{\mathrm{AC}}\) are parallel <=> A, B, C are collinear.

A, B, C, and D are distinct points.

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}, \overline{\mathrm{AC}}, \overline{\mathrm{AD}}\) are coplanar <=> A, B, C, D are coplanar

Coordinates Notation

⇒ \(‘ \bar{m} \perp \overline{\mathrm{L}} \text { ‘ means : }\) There exist two points A, B such that \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}=\bar{m} \text { and } \mathrm{AB} \perp \mathrm{L} \text {. }\)

⇒ \(‘ \bar{m} \| \overline{\mathrm{L}} \text { ‘ means: }\) There exist two points A, B such that \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}=\bar{m} \text { and } \mathrm{AB} \| \mathrm{L}\)

⇒ \({ }^{\prime} \bar{m} \subset \pi^{\prime} \text { means: }\) There exist two points A, B such that \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}=\bar{m} \text { and } \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \subset \pi\)

⇒ \({ }^{\prime} \bar{m} \subset \pi^{\prime} \text { means: }\) \(\overline{\mathrm{m}}\) is a point π.

Coordinates Solved Problems

Example.1. Show that the points (3, -2, 4),(1, 1, 1), (-1, 4, -2) are collinear. Hence find (C; A, B).

Solution.

Given

(3, -2, 4),(1, 1, 1), (-1, 4, -2)

Let A = (3,-2,4), B = (1,1,1) and C = (-1,4,-2)

∴ \(\mathrm{AB}=|\overline{\mathrm{AB}}|=|(1-3,1+2,1-4)|=|(-2,3,-3)|=\sqrt{(4+9+9)}=\sqrt{(22)}\),

BC \(=|(-2,3,-3)|=\sqrt{(4+9+9)}=\sqrt{(22)}\)

AC\(=|(-4,6,-6)|=\sqrt{(16+36+36)}=2 \sqrt{(22)} .\)

∴ AB + BC = AC.

∴ A, B, and C are collinear, and (C, A, B) = (-1-3):(1+1) = -2:1

⇒ \(\mathrm{OR}: \overline{\mathrm{AC}}=(-4,6,-6), \overline{\mathrm{CB}}=(2,-3,3)\)

Since \(\overline{\mathrm{AC}}=-2(2,-3,3)=-2 \overline{\mathrm{CB}}\) A, B, C are collinear.

Let (C, A, B) = λ1 : λ2

∴ \(\lambda_2 \overline{\mathrm{AC}}=\lambda_1 \overline{\mathrm{CB}}\)

⇒ \(\lambda_2(-4,6,-6)=\lambda_1(2,-3,3) \Rightarrow 2 \lambda_1=-4 \lambda_2\)

⇒ \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2=-2: 1\) ⇒ (C, A, B) = -2:1

Example.2. Show that the points (-1, -2, -1), (2, 3, 2), (4, 7, 6), and (1, 2, 3) form a parallelogram.

Solution.

Given

(-1, -2, -1), (2, 3, 2), (4, 7, 6), and (1, 2, 3)

Let A = (-1, -2, -1), B = (2, 3, 2), C = (4, 7, 6) and D = (1, 2, 3)

∴ \(\mathrm{AB}=\sqrt{\left[(2+1)^2+(3+2)^2+(2+1)^2\right]}=\sqrt{(43)}, \mathrm{BC}=6, \mathrm{CD}=\sqrt{(43)}, \mathrm{AD}=6\)

Also \(\mathrm{AC}=\sqrt{(155)} \text { and } \mathrm{BD}=\sqrt{3}\)

∴ AB = CD, BC = AD and AC ≠ BD.

Example.3. Find the center and radius of the sphere determined by the points (1, -5, -3), (0, -6, -1), (-2, -2, 3), (1, -2, 0).

Solution.

Given

(1, -5, -3), (0, -6, -1), (-2, -2, 3), (1, -2, 0)

The sphere is the set of points P = (x, y, z) where A = (a, b, c) and PA = r (a non-negative number) A is called the center and r is called the radius.

Let \(P_1=(1,-5,3), P_2=(0,-6,-1), P_3=(-2,-2,3) \text { and } P_4=(1,-2,0) \text {. }\)

∴ \(P_1 A=P_2 A=P_3 A=P_4 A \Rightarrow P_1 A^2=P_2 A^2=P_3 A^2=P_4 A^2\)

⇒ \((a-1)^2+(b+5)^2+(c-3)^2=(a-0)^2+(b+6)^2+(c+1)^2\) ………(1)

= \((a+2)^2+(b+2)^2+(c-3)^2=(a-1)^2+(b+2)^2+(c-0)^2\) ……..(2)

From (1) and (2): -2a – 2b – 8c = 2 ⇒ a + b + 4c = -1 …….(3)

-6a + 6b = -18 ⇒ a – b = 3

6b – 6c = -30 ⇒ b – c = -5

Solving 1 and 2 a = -1, b = -4, c = 1.

∴ Centre A = (-1, -4, 1).

Radius \(\mathrm{P}_1 \mathrm{~A}=\sqrt{\left[(a-1)^2+(b+5)^5+(c-3)^2\right]}=\sqrt{(4+1+4)}=3\)

Theorem. 2 If \(\overline{\mathrm{A}}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \overline{\mathrm{B}}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) and P is a point the line segment \(\mathrm{AB}\) in the ratio λ1 : λ2 (λ1 + λ2 ≠ 0), then \(P=\left(\frac{\lambda_2 \bar{x}_1+\lambda_1 \bar{x}_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2} \cdot \frac{\lambda_2 \bar{y}_1+\lambda_1 \bar{y}_1}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2} \cdot \frac{\lambda_2 \bar{z}_1+\lambda_1 \bar{z}_1}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right)\)

Proof: Let P = (x, y, z).

A, P, B = \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2\left(\lambda_1+\lambda_2 \neq 0\right)\)

⇔ \(\lambda_2 \overline{\mathrm{AP}}: \lambda_1 \overline{\mathrm{PB}}\)

⇔ \(\lambda_2\left(x-x_1, y-y_1, z-z_1\right)=\lambda_1\left(x_2-x, y_2-y, z_2-z\right)\)

⇔ \(\lambda_2\left(x-x_1\right)=\lambda_1\left(x_2-x\right)\), etc.

⇔ \(\left(\lambda_1+\lambda_2\right) x=\lambda_2 x_1+\lambda_1 x_2\), etc.

⇔ \(x=\frac{\lambda_2 x_1+\lambda_1 x_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, y=\frac{\lambda_2 y_1+\lambda_1 y_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, z=\frac{\lambda_2 z_1+\lambda_1 z_2}{\lambda_1+l_2}\)

⇔ \(\mathrm{P}=\left(\frac{\lambda_2 x_1+\lambda_1 x_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, \frac{\lambda_2 y_1+\lambda_1 y_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, \frac{\lambda_2 z_1+\lambda_1 z_2}{\lambda_1+I_2}\right),\left(\lambda_1+\lambda_2 \neq 0\right)\)

Note. 1. If λ1 = λ2, P wil be mid-point of AB and \(\mathrm{P}=\left(\frac{x_1+x_2}{2}, \frac{y_1+y_2}{2}, \frac{z_1+z_2}{2}\right)\)

2. \(\mathrm{A}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \mathrm{B}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \text {, }\)

P \(=\left(\frac{\lambda_2 x_1+\lambda_1 x_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, \frac{\lambda_2 y_1+\lambda_1 y_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, \frac{\lambda_2 z_1+\lambda_1 z_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right)\)

are three points and λ1, λ2 ∈ R such that λ1 + λ2 ≠ 0.

⇒ A, P, B are collinear.

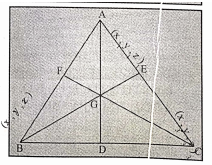

Theorem 3. If (xr, yr, zr), r = 1, 2, 3 are the vertices of a triangle, then its medians are concurrent and the point of concurrence trisects any median of the triangle.

Proof.

Given

If (xr, yr, zr), r = 1, 2, 3 are the vertices of a triangle

Let ABC be the triangle where A = (x1, y1, z1), B = (x2, y2, z2), C = (x3, y3, z3)

Let D, E, and F be the mid-points of the sides. AD, BE, and CF are the medians of ΔABC.

Now D = \(\left(\frac{x_2+x_3}{2}, \frac{y_2+y_3}{2}, \frac{z_2+z_3}{2}\right)\)

Let (G, A, D) = 2: 1.

∴ \(\mathrm{G}=\frac{2\left(\frac{x_2+x_3}{2}, \frac{y_2+y_3}{2}, \frac{z_2+z_3}{2}\right)+1\left(x_1, y_1\right)}{2+1}\)

= \(\frac{\left(x_1+x_2+x_3, y_1+y_2+y_3, z_1+z_2+z_3\right)}{3}\)

= \(\left(\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3}{3}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3}{3}, \frac{z_1+z_2+z_3}{3}\right)\)

Similarly, the point dividing BE in the ratio 2:1 is

⇒ \(\left(\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3}{3}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3}{3}, \frac{z_1+z_2+z_3}{3}\right)\) and the point dividing CF in the ratio 2: 1 is \(\left(\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3}{3}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3}{3}, \frac{z_1+z_2+z_3}{3}\right)\)

∴ G is the point common to AD, BE, and CF.

∴ Medians in a triangle are concurrent and the point of concurrence trisects each median. This point G is called the centroid.

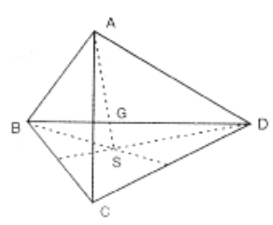

Coordinates Tetrahedron

Let A, B, C, D be four points such that \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABD}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ADC}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{BCD}}\) are four intersecting planes.

Then points A, B, C, and D are said to form a tetrahedron. A, B, C, and D are called vertices and the line segments AB, AD, AC, BC, BD, CD are called the edge, AB, CD; AD, BC; AC, BD are called three pairs of opposite edges.

Observe that for the tetrahedron:

(1) Each of the points A, B, C, and D is non-coplanar with the remaining three.

(2) Opposite edges from non-coplanar lines i.e., \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\) are non-coplanar, \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AD}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{BC}}\) are non-coplanar; \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{BD}}\) are non-coplanar.

(3) Four bounding planes \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABD}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ADC}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{BCD}}\) are triangular faces.

The point of concurrence of the line segments joining the vertices to their respective centroids of opposite triangular faces is called the centroid of the tetrahedron.

If all the edges are of equal length, then it is called a regular tetrahedron.

Theorem.4. If A = (x1, y1, z1), B = (x2, y2, z2), C = (x3, y3, z3), D = (x4, y4, z4) are the vertices of the tetrahedron ABCD, then the line segments joining the vertices to their respective centroids of opposite faces are concurrent and the point of concurrence divides each line segment in the ratio 3: 1.

Proof. Let S, P, Q, and R be the centroids of

⇒ \(\triangle \mathrm{BCD}, \triangle \mathrm{ACD}, \triangle \mathrm{ABD}, \triangle \mathrm{ABC}\) respectively.

∴ \(\S=\left(\frac{x_2+x_3+x_4}{3}, \frac{y_2+y_3+y_4}{3}, \frac{z_2+z_3+z_4}{3}\right)\)

Let G divide the line segments AS in the ration 3:1. Since A = (x1, y1, z1),

G = \(\left(\frac{3\left(\frac{x_2+x_3+x_4}{3}\right)+1 \cdot x_1}{3+1}, \frac{3\left(\frac{y_2+y_3+y_4}{3}\right)+1 \cdot y_1}{3+1}, \frac{3\left(\frac{z_2+z_3+z_4}{3}\right)+1 \cdot z_1}{3+1}\right)\)

i.e., G = \(\left(\frac{\left(x_1+x_2+x_3+x_4\right)}{4}, \frac{y_1+y_2+y_3+y_4}{4}, \frac{z_1+z_2+z_3+z_4}{4}\right)\)

Similarly, the points that divide the other line segments BP, CQ, and DR in the ratio 3: 1 can be shown to be G.

The line segments AS, BP, CQ, and DR are concurrent at G and each is divided in the ratio 3: 1 at G. G is called the centroid of the tetrahedron.

Example.1 Show that the following points are collinear, find A = (5, 4, 2), B = (8, -2, -7), C = (6, 2, -1) If A. B. C are collinear, find (C ; A, B)

Solution.

Given

A = (5, 4, 2), B = (8, -2, -7), C = (6, 2, -1)

Let P divide AB in the ratio 1 : λ (1 + λ ≠ 0).

∴ P = \(\left(\frac{5 \lambda+8}{1+\lambda}, \frac{-2+4 \lambda}{1+\lambda}, \frac{-7+2 \lambda}{1+\lambda}\right)\)

If possible, let P = C.

Then \(\left.\begin{array}{c}

\frac{5 \lambda+8}{1+\lambda}=6, \\

\frac{-2+4 \lambda}{1+\lambda}=2, \\

\frac{-7+2 \lambda}{1+\lambda}=-1

\end{array}\right\}\)

∴ λ = 2.

Since λ = 2 satisfies all three equations, A, B, and C are collinear.

∴ (C; A, B) = 1: 2.

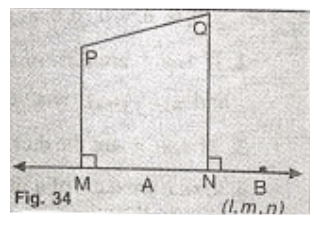

Coordinates Direction Cosines Of A Line

\(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) is a ray making angles α,β, γ respectively with \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OX}}\), \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OY}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OZ}}\).

Then the ordered triad \((\cos \alpha, \cos \beta, \cos \gamma)\) is called direction cosines triad of \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) i.e., \(\cos \alpha, \cos \beta, \cos \gamma\) in that order are called the direction cosines (d. cs.) of \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\)

The direction cosine triad is generally denoted by (l, m, n). Thus cosα = 1, cosβ = m, cosγ = n, and the d.cs. of are l, m, n.

Since the ray \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{QP}}\) makes angles 180° – α, 180° – β, 180° – γ respectively with \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OX}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OY}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OZ}}\) direction cosine triad of \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{QP}}\) is [(cos(180° – α), cos(180° – β), cos(180° – γ)]

i.e. (-cosα, -cosβ, -cosγ) i.e. (-l, -m, -n)

If L is a line parallel to then the two ordered triads (l, m, n) in that order and -l, -m, -n in that order are defined as the d.c.s of L. Sometimes d. cs. l, m, n are written as (l, m, n).

Theorem.5. If l, m, n are d.cs of a line, then l2 + m2 + n2 = 1.

Proof:

Let L be the line with d.cs. l, m, n

∴ (cos α, cos β, cos γ) = (l, m, n) or (-l, -m, -n)

If P(x, y, z) (≠G) is a point such that \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}} \| \mathrm{L}\) and OP = 1, then:

From Trigonometry

In \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{POX}}\) plane, \(\cos \alpha=\frac{x}{1}=x\);

In \( \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{POY}}\) plane, \(\cos \beta=\frac{y}{1}=y\);

In \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{POZ}}\) plane, \(\cos \gamma=\frac{z}{1}=z\);

OR

a = \((\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OX}})=(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}, \bar{i}) \Rightarrow \cos \alpha=\overline{\mathrm{OP}}, \bar{i}=(x, y, z) \cdot(1,0,0)=x \text {, etc. }\)

i.e. (x, y, z) = (l, m, n) or (-l, -m, -n)

But \(\mathrm{OP}^2=1 \Rightarrow x^2+y^2+z^2=1 \Rightarrow l^2+m^2+n^2=1 \text { etc. }\)

Note. (l, m, n) and (-l, -m, -n) are the only unit points on \(\stackrel{\leftrightarrow}{\mathrm{OP}}\) and l, m, n; -l, -m, -n are the d.cs. of L.

Coordinates Direction Ratios Or Direction Numbers Of A Line

L is a line and p(x, y, z) is a point such that \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}} \| \mathrm{L}\). Then the coordinates of any point on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\), other than the origin, are called the direction numbers of L. But any point, other than the origin, on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\) is (λx, λy, λz)(λ≠0). So in that order are called the direction numbers of the line L.

Clearly, the direction numbers for a line L are infinitely many and they are proportional. Further, the direction numbers cannot be 0, 0, 0.

The direction numbers are sometimes called as direction ratios(d. rs.)

The d.cs. (l, m, n) or (-l, -m, -n) of L are also d.rs. of L since each of (l, m, n) or (-l, -m, -n) is also a point on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\).

If P(x, y, z) then unit points on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\) are

⇒ \(\left(\frac{x}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{y}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{z}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}\right)\),

⇒ \(\left(\frac{-x}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{-y}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{-z}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}\right)\)

Hence if d.rs. of L are x, y, z then d.cs. of L are

⇒ \(\frac{x}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{y}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{z}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}\)

⇒ \(\frac{-x}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{-y}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}, \frac{-z}{\sqrt{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)}}\)

Note.1. D.rs. of the coordinate axes are respectively x, 0, 0; 0, y, 0; 0, 0, z (x≠0, y≠0, z≠0)

2. If x, y, z are d.rs. of a line L, there exists a point p(x, y, z) such that \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}} \| \mathrm{L}\) and \(x \bar{i}+y \bar{j}+z \bar{k}\) is a vector along \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\) i.e. a vector along L.

3. If l, m, n are the d.cs. of a line L then \(l \bar{i}+m \bar{j}+n \bar{k}\) is a unit vector L.

4. l, m, n are d.cs. of a line L. If any two of the d.cs. and the sign of the third is known, then the d.cs. of L can be found.

For example, \(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2}, n\) are d.cs. of L and n < 0 ⇒ \(n=-\sqrt{\left(1-\frac{1}{4}-\frac{1}{4}\right)}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\)

⇒ d.cs. of L are \(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{2},-\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\)

example. The d.cs. of the line with d.rs. (3, 2, 6) are

± \(\frac{3}{\sqrt{(9+4+36)}}, \pm \frac{2}{(9+4+36)}, \pm \frac{6}{\sqrt{(9+4+36)}}\)

i.e. \(\frac{3}{7}, \frac{2}{7}, \frac{6}{7} ;-\frac{3}{7},-\frac{2}{7},-\frac{6}{7}\)

Theorem.6. If P=(x1, y1, z1), Q = (x2, y2, z2) then x2 – x1, y2 – y1, z2 – z1 are d.rs. of \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}\).

Proof. Let OPQR be a parallelogram

Then \(\overline{\mathrm{OR}}=\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}=\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)\)

⇒ \(\mathrm{R}=\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)\)

∴ d.rs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OR}} \text { are } x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\)

∴ d.rs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}} \text { are } x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\)

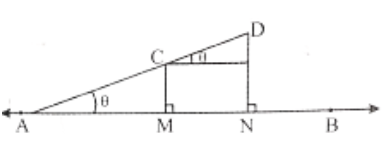

Coordinates Projection Of A Line Segment On Another Line

The projection of a line segment CD on a line \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) is MN where M, N are the feet of the perpendiculars on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\).

If \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\) make an angle θ with \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\), then the projection of CD on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) is MN = CDcosθ.

Let \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) ne a line. On \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) let the projection of C, and D be M and, N respectively.

Then the projection of CD on the line \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) is \(\overline{\mathrm{CD}}\). \(\frac{\overline{\mathrm{MN}}}{|\overline{\mathrm{MN}}|}\) in the direction \(\overline{\mathrm{MN}}\).

Theorem.7. If \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) is a ray with d.cs. l, m, n, and P = (x1, y1, z1), Q = (x2, y2, z2) are two points, then the projection of PQ on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) in the direction \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) is (x2 – x1)l + (y2 – y1)m + (z2 – z1)n.

Proof.

PQ = \(\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)\)

Unit vector along \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) = e = (l, m, n)

∴ Projection PQ on \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) in the direction \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\)

= PQ. e = \(\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_1, z_2-z_1\right)(l, m, n)\)

= \(l\left(x_2-x_1\right)+m\left(y_2-y_1\right)+n\left(z_2-z_1\right)\)

Coordinates Angles Between Two Lines

Theorem.8. If l1, m1, n1 and l2, m2, n2 are d.cs. of two lines L1, L2 then an angle θ between them is given by cosθ = l1l2 + m1m2 + n1n2

Proof. Let P = (l1, m1, n1) and Q = (l2, m2, n2) and

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{OP}}=\bar{e}_1=\left(l_1, m_1, n_1\right) \overline{\mathrm{OQ}}=\bar{e}_2=\left(l_2, m_2, n_2\right)\)

∴ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}} \| \mathrm{L}_1 \text { and } \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}} \| \mathrm{L}_2\)

Since θ is one of the angles between L1, L2, we take \((\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}})=\theta\)

∴ cos θ = \(\cos (\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OQ}})\) = cos (OP, OQ) = cos(e1, e2)

= e1.e2 = (l1, m1, n1).(l2, m2, n2) = l1l2 + m1m2 + n1n2

∴ Angles between L1, L2 are θ, 180° – θ.

Note.1. \(\sin \theta=\left|\bar{e}_1 \times \bar{e}_2\right|=\left|\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1, n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1, l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1\right)\right|\)

= \(\sqrt{\left[\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1\right)^2+\left(n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1\right)^2+\left(l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1\right)^2\right]}=\sqrt{\left[\sum\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1\right)^2\right]}\)

OR: \(\sin ^2 \theta=1-\cos ^2 \theta=\left(l_1^2+m_1^2+n_1^2\right)\left(l_2^2+m_2^2+n_2^2\right)-\cos ^2 \theta\)

= \(\left(l_1^2+m_1^2+n_1^2\right)\left(l_2^2+m_2^2+n_2^2\right)-\left(l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2\right)^2\)

= \(\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1\right)^2+\left(n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1\right)^2+\left(l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1\right)^2\)

Coordinates Lagrange’s Identity

For any real numbers l1, m1, n1, l2, m2, n2

(l12 + m12 + n12)2 + (n1l2 – n2l1)2 + (l1m2 – l2m1)2

By simplifying L.H.S and regrouping the terms we can show that L.H.S = R.H.S.

Coordinates Solved problems

Example.1. Calculate the cosine of the angle A of the triangle with vertices a(1, -1, 2), B(6, 11, 2), C(1, 2, 6).

Solution.

Given A = (1,-1,2), B – (6,11,2), C = (1,2,6)

We have \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}=(6-1,11+1,2-2) \text { and } \overline{\mathrm{AC}}=(1-1,2+1,6-2)\)

cos \(\mathrm{A}=\frac{\overline{\mathrm{AB}} \cdot \overline{\mathrm{AC}}}{|\overline{\mathrm{AB}}||\overline{\mathrm{AC}}|}=\frac{(5,12,0) \cdot(0,3,4)}{\sqrt{25+144+0} \cdot \sqrt{0+9+16}}=\frac{0+36+0}{13 \times 5}=\frac{36}{65}\)

OR: D.rs. of \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\) are (6-1, 11+1, 2+2) and

(1-1,2+1,6-2) i.e., (5,12,0), (0,3,4)

∴ D.cs. of \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}} \text { are }\left(\frac{5}{13}, \frac{12}{13}, 0\right),\left(0, \frac{3}{5}, \frac{4}{5}\right) \text {. }\)

∴ \(\cos A=\frac{5}{13} \cdot 0+\frac{12}{13} \cdot \frac{3}{5}+0 \cdot \frac{4}{5}=\frac{36}{65} .\)

Example.2. If (l1, m1, n1), (l2, m2, n2), (l3, m3, n3) are the d.cs. of three mutually perpendicular rays, then find the d.cs. of a ray whose d.rs. are l1 + l2 + l3, m1 + m2 + m3, n1 + n2 + n3. Hence, it shows that the ray is equally inclined to the given rays.

Solution.

Given

If (l1, m1, n1), (l2, m2, n2), (l3, m3, n3) are the d.cs. of three mutually perpendicular rays

Let L1, L2, L3 be three mutually perpendicular rays whose d.cs. are (l1,m1,n1), (l2,m2,n2), (l3,m3,n3)

∴ \(l_1^2+m_1^2+n_1^2=1, l_2^2+m_2^2+n_2^2=1, l_3^2+m_3^2+n_3^2=1 \text {, }\)

⇒ \(l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2=0, l_2 l_3+m_2 m_3+n_2 n_3=0, l_3 l_1+m_3 m_1+n_3 n_1=0\)

Now \(\left(l_1+l_2+l_3\right)^2+\left(m_1+m_2+m_3\right)^2+\left(n_1+n_2+n_3\right)^2\)

= \(\left(l_1^2+m_1^2+n_1^2\right)+\left(l_2^2+m_2^2+n_2^2\right)+\left(l_3^2+m_3^2+n_3^2\right)\)

+ \(2\left(l_1 l_2+m_1 m_2+n_1 n_2\right)+2\left(l_2 l_3+m_2 m_3+n_2 n_3\right)+2\left(l_3 l_1+m_3 m_1+n_3 n_1\right)=3\)

∴ d.cs. of the ray L whose d.rs. are \(l_1+l_2+l_3, m_1+m_2+m_3 \text {, are } n_1+n_2+n_3\)

are \(\frac{l_1+l_2+l_3}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{m_1+m_2+m_3}{\sqrt{3}}, \frac{n_1+n_2+n_3}{\sqrt{3}}\)

If \(\left(\mathrm{L}, \mathrm{L}_1\right)=\theta \text {, then } \cos \theta=\frac{l_1\left(l_3+l_2+l_3\right)+m_1\left(m_1+m_2+m_3\right)+n_1\left(n_1+n_2+n_3\right)}{\sqrt{3}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\)

i.e., \(\theta={Cos}^{-1}(1 / \sqrt{3})\). Similarly, we can have \(\left(\mathrm{L}, \mathrm{L}_2\right)=\left(\mathrm{L}, l_3\right)={Cos}^{-1}(1 / \sqrt{3}) \text {. }\)

∴ L is equally inclined with L1, L2, L3.

Example.3. L1, L2, L3 are three concurrent rays whose d.cs. are (l1, m1, n1), (l2, m2, n2), (l3, m3, n3) respectively. Prove that L1, L2, L3 are coplanar <=> \(\left|\begin{array}{lll}

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2 \\

l_3 & m_3 & n_3

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Solution.

Given

L1, L2, L3 are three concurrent rays whose d.cs. are (l1, m1, n1), (l2, m2, n2), (l3, m3, n3) respectively.

Rays L1, L2, L3 are concurrent and unit vectors along L1, L2, L3 are

⇒ \(l_1 \bar{i}+m_1 \bar{j}+n_1 \bar{k}, l_2 \bar{i}+m_2 \bar{j}+n_2 \bar{k}, l_3 \bar{i}+m_3 \bar{j}+n_3 \bar{k} \text { i.e. }\left(l_1, m_1, n_1\right),\left(l_2, m_2, n_2\right),\left(l_3, m_3, n_3\right) \text {. }\)

L1, L2, L3 are coplanar ⇔ \(\left[\left(l_1, m_1, n_1\right),\left(l_2, m_2, n_2\right),\left(l_3, m_3, n_3\right)\right]=0 \Leftrightarrow\left|\begin{array}{lll}

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2 \\

l_3 & m_3 & n_3

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Example.4. Find the foot of the perpendicular from p(1, 8, 4) to the line \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) where A = (0, -11, 4), B = (2, -3, 1).

Solution. Let (Q; A, B) = 1 : λ (1+λ≠0)

∴ Q = \(\left(\frac{2}{1+\lambda}, \frac{-3-11 \lambda}{1+\lambda}, \frac{1+4 \lambda}{1+\lambda}\right)\)

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}=\left(\frac{2}{1+\lambda}-1, \frac{-3-11 \lambda}{1+\lambda}-8, \frac{1+4 \lambda}{1+\lambda}-4\right) \text { and } \overline{\mathrm{AB}}=(2,-3+11,1-4)=(2,8,-3)\)

If \(\mathrm{PQ} \perp \mathrm{AB} \text {, then } \overline{\mathrm{AB}} \cdot \overline{\mathrm{PQ}}=0\)

∴ \(2\left(\frac{2-1-\lambda}{1+\lambda}\right)+8\left(\frac{-3-11 \lambda-8-8 \lambda}{1+\lambda}\right)-3\left(\frac{1+4 \lambda-4-4 \lambda}{1+\lambda}\right)=0\)

⇒ \(2-2 \lambda-88-152 \lambda+9=0 \Rightarrow 154 \lambda=-77 \Rightarrow \lambda=-\frac{1}{2} \Rightarrow 1: \lambda=1:-\frac{1}{2}\)

∴ Foot of the perpendicular from P to \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}=\left(\frac{2}{(1 / 2)}, \frac{-3+\frac{11}{2}}{(1 / 2)}, \frac{1-2}{(1 / 2)}\right)=(4,5,-2)\)

Note. Length of the perpendicular from P to the line

∴ \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}=\sqrt{(4-1)^2+(5-8)^2+(-2-4)^2}=3 \sqrt{6}\)

Example.5. If P, Q, R, S are the points (-1, 2, 4), (1, 0, 5), (3, 4, 5), (4, 6, 3), find the projection of \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}} \text { on } \overleftrightarrow{R S}\) in the direction of \(\overline{R S}\)

Solution.

Given

If P, Q, R, S are the points (-1, 2, 4), (1, 0, 5), (3, 4, 5), (4, 6, 3)

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}=(2,-2,1) \text { and } \overline{\mathrm{RS}}=(1,2,-2)\)

∴ Projection of \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}} \text { on } \overrightarrow{\mathrm{RS}}\) in the direction of \(\overline{\mathrm{RS}}\)

= \(\frac{\overline{\mathrm{PQ}} \cdot \overline{\mathrm{RS}}}{|\overline{\mathrm{RS}}|}=\frac{(2,-2,1),(1,2,-2)}{|(1,2,-2)|}=\frac{(2) 1+(-2) 2+1(-2)}{\sqrt{[1+4+4]}}=\frac{-4}{3}\)

Example.6. Find the area of the △OAB where O is the origin, A = (x1, y1, z1) and B = (x2, y2, z2).

Solution.

Given

O is the origin, A = (x1, y1, z1) and B = (x2, y2, z2)

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \text { and } \overline{\mathrm{OB}}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \text {. }\)

Area of the \(\Delta \mathrm{OAB}=\frac{1}{2}|\overline{\mathrm{OA}} \times \overline{\mathrm{OB}}|\)

But \(\overline{\mathrm{OA}} \times \overline{\mathrm{OB}}=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\bar{l} & \bar{j} & \bar{k} \\

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2

\end{array}\right|=\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1, z_1 x_2-x_1 z_2, x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right)\)

∴ Area of \(\Delta \mathrm{OAB}=\frac{1}{2} \sqrt{\left\{\left(y_1 z_2-y_2 z_1\right)^2+\left(z_1 x_2-z_2 x_1\right)^2+\left(x_1 y_2-x_2 y_1\right)^2\right\}} \text { sq. units }\)