Chapter 8 Cyclic Groups 8.1 Before Defining A Cyclic Group, We Prove A Theorem That Serves As A Motivation For The Definition Of Cyclic Group.

Theorem. Let G be a group and a be an element of G. Then \(\left.\mathbf{H}=\left\{a^n\right\rangle \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\) is a subgroup of G. Further H is the smallest of subgroups of G which contain the element a.

Proof. Let (G, .) be a group and a ∈ G .

For 1 ∈ Z we have \(a^{\prime}=a \in \mathbf{H}\) which shows that H is nonempty.

Suppose now that \(a^r, a^s \in \mathbf{H}\). We will show that

1)\(a^r a^s \in \mathbf{H}\) and \(\left(a^r\right)^{-1}\) \in \mathbf{H}[/latex] which will prove that H is a subgroup of G.

⇒ \(a^r, a^s \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow r, s \in \mathbf{Z} \Rightarrow r+s,-r \in \mathbf{Z}\)

∴ \(a^r \cdot a^s=a^{r+s} \in \mathbf{H} \text { and }\left(a^r\right)^{-1}=a^{-r} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ H is a subgroup of G.

2)Suppose K is any other subgroup of G such that a ∈ K

Then \(a^n \in \mathbf{K} \forall n \in \mathbf{Z}\).

∴ \(\mathbf{H} \subset \mathbf{K}\) which shows that H is the subset of every subgroup of G which contains a.

Thus H is the smallest of subgroups of G which contain a.

Chapter 8 Cyclic Groups 8.2 Cyclic Subgroup Generated By a

Definition. Suppose G is a group and a is an element of G. Then the subgroup \(\mathbf{H}=\left\{a^n / n \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\) is called a cyclic subgroup generated by a. a is called a generator of H.

This will be written as H = < a > or (a) or {a}.

Cyclic group.

Definition. Suppose G is a group and there is an element a ∈ G such that \(\mathbf{G}=\left\{a^n \mid n \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\) Then G is called a cyclic group and a is called a generator of G.

We denote G by < a >.

Thus a group consisting of elements that are only the power of a single element belonging to it is a cyclic group.

Let G be a group and a ∈ G: If the cyclic subgroup of G generated by a i.e. < a > is finite, then the order of the subgroup i.e. \(\mid<a>\mid\) is the order of a. If < a > is infinite then we say that the order of a is infinite.

Note. If G is a cyclic group generated by a, then the elements of G will be \( \ldots a^{-2}, a^{-1}, a^0=e, a^1, a^2, \ldots\) in multiplicative notation and the elements of G will be\(\ldots-2 a,-a, 0 a=0, a, 2 a, \ldots\)in additive notation. The elements of G are not necessarily distinct. There exist finite and infinite cyclic groups.

Definition Of Cyclic Groups With Examples

Example 1. G = {1,-1} is a multiplicative group. Since \((-1)^0=1,(-1)^1=-1,(\mathbf{G}, .)\) is a cyclic group generated by – 1 i.e. G = < -1 > • It is a finite cyclic group of order 2 and 0(-l) = 2.

Example 2. G = {…- 4, – 2,0,2,4,….} is an additive group.

Since G = \(\mathbf{G}=\{2 m / m=\ldots-1,0,1,2, \ldots\}\), G is a cyclic group generated by 2 i.e.

G = < 2 > . It is an infinite cyclic group.

Example 3. (Q, +), \((Q^+, •)\) are groups but are not cyclic.

Example 4. \(\left\{12^n / n \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\) is a cyclic group w.r.t. usual multiplication.

Its generators are 12,1/12.

Example 5. <18> is a cyclic subgroup of the cyclic group \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{36},+_{36}\right)\), and since

⇒ \(18^1=18,18^2=18+{ }_{36} 18=0\)

⇒ \(18^3=18^2+_{36} 18=18,18^4=18^3++_{36} 18=18+{ }_{36} 18=0, \ldots \ldots,\) ,we have < 18 > = {0,18}.

Example 6. Let \(\mathbf{G}=\mathbf{S}_3\) and H = {(1),(13)}.

Then the left cosets of H in G are :

(1) H = H,(l 2) \(H = \left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 2 & 1

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 3 & 2

\end{array}\right) \mathbf{H}\)

(1 3)H = H,(2 3)H = (1 2 3)H. (Analogous results hold for right cosets)

Theorem 1. Let (G, .) be a cyclic group generated by a. If O(a) = n, then \(a^n=e \text { and }\left\{a, a^2, \ldots . a^{n-1}, a^n=e\right\}\) is precisely the set of distinct elements belonging to G where e is the identity in the group (G)

Theorem 2. If G is a finite group and \(a \in \mathbf{G} \text {, then } o(a) / o(\mathbf{G})\)

Proof. G is a finite group. Let o (G) = m .

Let H be the cyclic subgroup of G generated by a.

Let o (a) = n

∴ o (H) = n (Vide Theorem 25, Art. 2.17.)

But by Lagrange’s Theorem, o (H) / o (G).

n / o(G) i.e. o (a) / o(G).

Note. If o(a) = n and a ∈ G , then \(o(\mathbf{H}) \leq o(\mathbf{G})\).

Theorems On Cyclic Groups With Proofs And Examples

Theorem 3. If G is a finite group of order n and if a ∈ G, then \(a^n=e\) (identity in G).

Given

If G is a finite group of order n and if a ∈

Proof. Let o (a) = d and \(a^d=e \text { and } d \leq n\).

If H is a cyclic subgroup generated by a, then o (H) = d = o (a).

But by Lagrange’s Theorem, o (H) / o (G) i.e. d/n.

∴ ∃ a positive integer q such that n = dq.

∴ \(a^n=a^{d q}=\left(a^d\right)^q=e^q=e\)

Note. the statement of the above theorem may be: If G is a finite group, then for any \(a \in \mathbf{G}, a^{0(G)}=e\).

Cyclic Groups Solved Problems

Example 1. Let \(\mathbf{A}=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right], \mathbf{B}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

0 & 1 \\

-1 & 0

\end{array}\right], \mathbf{C}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

-1 & 0 \\

0 & -1

\end{array}\right] \text { and } \mathbf{D}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

0 & -1 \\

1 & 0

\end{array}\right]\).

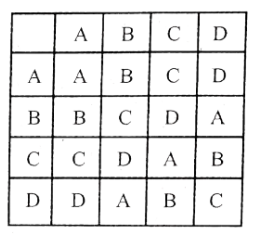

We have that G = {A, B, C, D} with matrix multiplication as operation is a group whose composition table is given below. Show that G is a cyclic group with generator B.

Solution: here O(G) = 4, A is the identity element in G. Now we can see that

⇒ \(\mathbf{B}^1=\mathbf{B}, \mathbf{B}^2=\mathbf{B} \cdot \mathbf{B}=\mathbf{C}\)

⇒ \(\mathbf{B}^3=\mathbf{B}^2 \cdot \mathbf{B}=\mathbf{C} \cdot \mathbf{B}=\mathbf{D}\)

⇒ \(\mathbf{B}^4=\mathbf{B}^3 \cdot \mathbf{B}=\mathbf{D} \cdot \mathbf{B}=\mathbf{A}\)

Thus B ∈ G generated the group G and hence G is a cyclic group with B as a generator

i.e. G=<B>.

Note that O(B)=4=O(G) and \(\mathbf{B}^{\mathbf{O}(\mathbf{G})}=\mathbf{A}\).

Also, G is abelian.

Note: A, C, and D are not generators of group G.

Example 2. Prove that (Z, +) is a cyclic group.

Solution: (Z, +) is a group and 1 ∈ Z.

When we take additive notation in Z, a becomes na.

⇒ \(1^0=0.1=0,1^1=1.1=1,1^2=2.1=2\) etc.

Also \(1^{-1}=-1,1^{-2}=-2.1=-2\) etc.

∴ 1 is a generator of the cyclic group (Z, +) i.e. Z = <1>.

Similarly, we can prove that Z = < -1 > .

Note 1. (Z, +) has no generators except 1 and – 1.

For: Let r = 4 ∈ Z.

We cannot write every element m of z in the form m = 4n. For example, 7 = 4n is not possible for n ∈ Z. Thus when r is an integer greater than 1, r is not a generator of Z.

Similarly, when r is an integer less than – 1 also, r is not a generator of Z.

Thus (Z, +) is a cyclic group with only two generators 1 and – l.

2. (Z,- +) is an infinite abelian group and it is a cyclic group.

Classification Of Cyclic Groups With Detailed Explanation

Example 3. Show that G = {1, -1, i, -i} the set of all fourth roots of unity is a cyclic group w.r.t. multiplication.

Solution.

Given

G = {1, -1, i, -i}

Clearly (G,.) is a group. We see that

⇒ \((i)^1=i, i^2=i, i=-1, i^3=i^2 \cdot i=-1 . i=-i\)

⇒ \(i^4=i^3 \cdot i=(-i) i=1\)

Thus all the elements of G are the powers of i ∈ G i.e. G =< i >

Similarly, we can have G =< -i >. Note that 0 (G) = 0 (i) = 0 (-i) = 4 .

Also, G is abelian.

Note. (G, .) is a finite abelian group which is cyclic.

Example 4. Show that the set of all cube roots of unity is a cyclic group w.r.t. multiplication.

Solution. If ω is one of the complex cube roots of unity, we know that G = \({l,ω, ω^2}\) is a group w.r.t. multiplication. We see that \(\omega^1=\omega, \omega^2=\omega \omega=\omega^2, \omega^3=1\) .

∴ Then elements of G are the powers of the single element ω ∈ G

∴ G = <ω>

We can also have \(\mathbf{G}=\left\langle\omega^2\right\rangle\).

(∵ \(\left.\left(\omega^2\right)^1=\omega^2,\left(\omega^2\right)^2=\omega,\left(\omega^2\right)^3=1\right)\)

Example 5. Prove that the group \( \left(\{1,2,3,4\}, \times_5\right)\) is cyclic and. write its generators.

Solution. \(2 x_5 2=4,2 \times_5 2 x_5 2=4 x_5 2=3,2 \times_5 2 x_5 2 x_5 2=1,2 x_5 2 x_5 2 x_5 2 x_5 2=2\)

⇒ 2 is a generator of the group ⇒ the group is cyclic.

Also group 3 is a generator.

1, 4 are not generators of the cyclic group.

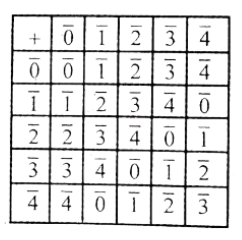

Example 6. Show that \(\left(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_5,+\right)\)where \(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_S\) is the set of all residue classes modulo 5, is a cyclic group w.r.t. addition (+) of residue classes.

Solution. The composition table for the group \(\left(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_5,+\right)\) is;

We can have

⇒ \(\overline{1}=\overline{1},(\overline{1})^2=2(\overline{1})=\overline{1}+\overline{1}=\overline{2}\)

⇒ \((\overline{1})^3=\left(\overline{1}^2\right)+(\overline{1})=\overline{2}+\overline{1}=\overline{3}\)

⇒ \((\overline{1})^4=(\overline{1})^3+(\overline{1})=\overline{3}+\overline{1}=\overline{4}\)

Thus \(\left(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_5,+\right)\) is a cyclic group with 1 as generator.

∴ \(\left(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_5,+\right)=\langle\overline{1}\rangle\)

Similarly, we can prove that 2,3,4 are also generators of this cyclic group.

Example 7. Show that \(\left(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_m,+\right)\) , where \(\overline{\mathbf{z}}_m\)is the set of all residue classes modulo m and + is the residue class addition, is a cyclic group.

Solution. We have \(\left(\overline{\mathbf{Z}}_m,+\right)\) as an abeian group.

We can have \((\overline{1})^1=1,(\overline{1})^2=2(\overline{1})=\overline{1}+\overline{1}=\overline{2}\)

… … … … …

⇒ \((\overline{1})^{m-1}=(\overline{1})^{m-2}+(\overline{1})^1=(m-2) \overline{1}+\overline{1}=\overline{m-1}\)

We have nZ = {0, ± n, ± 2n, ± 3n, …}

∴ (nZ, +) = <n > and (nZ, +) = <-n >.

Note. (nZ, +) is a subgroup of the group (Z, +) and (nZ, +) is cyclic.

Cyclic Groups 8.3. Some Properties Of Cyclic Groups

Theorem 4. Every cyclic group is an abelian group.

Proof. Let G = < a > by a cyclic group.

We have \(\mathbf{G}=\left\{a^n / n \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\)

Let \(a^r, a^s \in \mathbf{G}\)

∴ \(a^r \cdot a^s=a^{r+s}\)

= \(a^{s+r}=a^s \cdot a^r\)

G is abelian.

Note. Converse is not true i.e. every abelian group is not cyclic. Klein’s group of 4 is an example.

e = \(e^2=e^3=e^4 ; a=a, a^2=e, a^3=a, a^4=e\)

b = \(b, b^2=e, b^3=b, b^4=e, c=c, c^2=e, c^3=c, c^4=e\)

None of the elements of G generates G even though G is abelian

i.e. G is abelian but not cyclic.

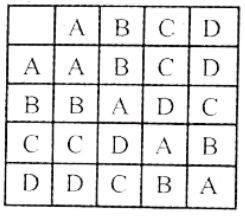

example. Consider the set G = {A, B, C, D} where

⇒ \(\mathbf{A}=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right], \mathbf{B}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

-1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right], \mathbf{C}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 0 \\

0 & -1

\end{array}\right], \mathbf{D}=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

-1 & 0 \\

0 & -1

\end{array}\right]\)

and the matrix multiplication as the binary composition on G.

Composition table is :

Clearly, G is a finite abelian group (of order 4) with identity element A.

Also \(\mathbf{B}^2=\mathbf{A}, \mathbf{C}^2=\mathbf{A} \text { and } \mathbf{D}^2=\mathbf{A}\)

i.e. each element is of order 2 (except the identity A )

∴ G is abelian.

Hence there is no element of order 4 in G.

∴ G is not cyclic and hence every finite abelian group is not cyclic.

Solved Problems On Cyclic Groups Step-By-Step

Theorem 5. If a is a generator of a cyclic group G, then \(a^{-1}\) is also a generator of G.

If \(\mathbf{G}=\langle a\rangle \text { then } \mathbf{G}=\left\langle a^{-1}\right\rangle\).

Proof. Let G = <a> be a cyclic group generated by a. Let \(a^r \in \mathbf{G}, r \in \mathbf{Z}\)

We have \(a^r=\left(a^{-1}\right)^{-r} \text { since }-r \in \mathbf{Z}\)

∴ Each element of G is generated by \(a^{-1}\)

Thus \(a^{-1}\) is also a generated of G

i.e., \(\mathrm{G}=\left\langle a^{-1}\right\rangle\)

Theorem 6. Every subgroup of the cyclic group is cyclic.

Proof. Let G =<a>. Let H be a subgroup of G. Since H is a subgroup of G, we take that every element of H is an element of G. Thus it can be expressed as \(a^n\) for some n ∈ Z.

Let d be the smallest of the positive integers such that \(a^n \in \mathbf{H}\). We will now prove that \(\mathbf{H}=\left\langle a^d\right\rangle\).

Let \(a^m \in \mathbf{H} \text { where } m \in \mathbf{Z}\)

By division algorithm, we can find integers g and r such that

m = dq + r 0 < r < d .

∴ \(a^m=a^{d q+r}=a^{d q} a^r=\left(a^d\right)^q \cdot a^r\)

But \(a^d \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow\left(a^d\right)^q \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{d q} \Rightarrow a^{-d q} \in \mathbf{H}\)

Now \(a^m, a^{-d q} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^m \cdot a^{-d q} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{\mu n-d q} \in \mathbf{H} \quad \Rightarrow a^r \in \mathbf{H}\)

But 0 < r < d and \(a^r \in \mathbf{H}\) is a contradiction to our assumption that of smallest integer such that \(a^d \in \mathbf{H}\) .

∴ r = 0

∴ m = dq

i.e. \(a^m=\left(a^d\right)^q\) which shows that every \(a^n \in \mathbf{H}\) can be written as \(\left(a^d\right)^q, q \in \mathbf{Z}\).

∴ \(\mathbf{H}=\left\langle a^d\right\rangle\)

Hence a subgroup LI of G is cyclic and ad is a generator of H

Note: The converse of the above theorem is not true.

That is though the subgroup of a group is cyclic, the group need not be cyclic.

We know that (Z, +) is a subgroup of (R, +) . We also have that (Z, +) is a cyclic group generated by 1 and – 1. But (R, +) is not cyclic. group since it has no generators.

Cor. Every subgroup of a cyclic group is a normal subgroup.

Proof. Every cyclic group is abelian (vide Theorem 4) and every subgroup of a cyclic group is cyclic (vide Theorem 6).

∴ Every subgroup of a cyclic group is abelian. Hence every subgroup of a cyclic group is a normal subgroup.

Cyclic Groups 8.4. Classification Of Cyclic Groups

Let G =<a>. Then

1)G is a finite cyclic group if there exist two unequal integers l and m such that \(a^{\prime}=a^m\)

If a group G of order n is cyclic, then G is a cyclic group of order n.

2)G is an infinite cyclic group if for every pair of unequal integers l and m, \(a^l \neq a^m\)

Theorem 7. The quotient group of a cyclic group is cyclic.

Proof. Let G =<a> be a cyclic group with a as a generator.

Let N be a subgroup of G. Since G is abelian we take that N is normal in G.

We know that \(\frac{\mathbf{G}}{\mathbf{N}}=\{\mathbf{N} x / x \in \mathbf{G}\}\)

Now \(a \in \mathbf{G} \Rightarrow \mathbf{N} a \in \mathbf{G} / \mathbf{N} \Rightarrow\langle\mathbf{N} a\rangle \subseteq \mathbf{G} / \mathbf{N}\)

Also \(\mathbf{N} x \in \mathbf{G} / \mathbf{N} \Rightarrow x \in \mathbf{G}=\langle a\rangle\)

∴ \(x=a^n\) for some n ∈ Z.

∴ Nx = Na = N(a a a ……n times) when n is a +ve integer

= NaNa……n times = \((\mathbf{N} a)^n\)

We can prove that \(\mathbf{N} x=(\mathbf{N} a)^n\) when n = 0 or a negative integer.

∴ \(\mathbf{N} x \in \mathbf{G} / \mathbf{N} \Rightarrow \mathbf{N}(x) \in\langle\mathbf{N} a\rangle\)

∴ \(\mathbf{G} / \mathbf{N} \subseteq\langle\mathbf{N} a\rangle\)

∴ From (1) and (2) G/N = <Na> which shows that G/N is cyclic.

Theorem 8. If p is a prime number then every group of order p is a cyclic group i.e. a group of prime order is cyclic.

Proof. Let p ≥ 2 be a prime number and G be a group such that O(G) ≥ p.

Since the number of elements is at least 2, one of the elements of G will be different from the identity e of G. Let that element be a.

Let <a > be the cyclic subgroup of G generated by a.

∴ \(a \in<a>\Rightarrow<a>\neq\{e\}\)

Let <a> have order h,

∴ By Lagrange’s Theorem h \ p

But p is a prime number.

∴ h = 1 of h = p

But \(<a>\neq\{e\}\)

∴ h ≠ 1 and hence h = p

∴ O( <a>) = p i.e. <a>= G which shows that G is a cyclic group.

Note 1. We have by the above theorem if O(G) – p, a prime number, then every element of G which is not an identity is a generator of G. Thus the number of generators of G having p elements is equal to p – 1.

2. Every group G of orders less than 6 is abelian. For: We know that every group G of order less than or equal to 4 is abelian.

Also, we know that every group of prime order is cyclic and every cyclic group is abelian. If O(G) = 5, then G is abelian.

Thus the smallest non-abelian group is of order 6.

3. Is the converse of the theorem “Every group of prime order is cyclic” true? Not true.

For 4th roots of unity w.r.t. multiplication forms a cyclic group and 4 is not a prime number. Thus a cyclic group need not be of prime order.

Cyclic Groups 8.5 Some More Theorems on Cyclic Groups

Theorem 9. If a finite group of order n contains an element of order n, then the group is cyclic.

Proof. Let G be a finite group of order n. Let a ∈ G such that O (a) = n

i.e. \(a^n=e\) where n is the least positive integer.

If H is a cyclic subgroup of G generated by a i.e. if \(\mathbf{H}=\left\{a^r / r \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\) then O (H) = n because the order of the generator a of H is n.

Thus H is a cyclic subgroup of G and O (H) = 0 (G).

Hence H = G and G itself is a cyclic group with a as a generator.

Note. Suppose G is a finite group of order n and we are to determine whether G is cyclic or not.

For this we find the orders of the elements of G and if a ∈ G exists such that O (a) = n then G will be a cyclic group with a as a generator.

Exercises On Cyclic Groups With Solutions

Theorem 10. Every finite group of composite order possesses proper subgroups.

Proof. Let G be a finite group of composite order mn where m(≠) and n(≠) are positive integers.

1)Let G = <a>. Then O (a) = O (G) = mn

∴ \(a^{m n}=e \Rightarrow\left(a^n\right)^m=e \Rightarrow \mathrm{O}\left(a^n\right) \text { is finite and } \leq m\)

Let \(\mathrm{O}\left(a^n\right)=p\). where p < m.

Then \(\left(a^n\right)^p=e \Rightarrow a^{n p}=e\)

But p < m ⇒ np < mn

Thus \(a^{n p}=e\) where np < mn .

Since O (a) = mn,\(a^{n p}=e\) is not possible, so p = m

∴ \(\mathbf{O}\left(a^n\right)=m\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H}=\left\langle a^n\right\rangle\) is a cyclic subgroup of G and \(\mathbf{O}(\mathbf{H})=\mathbf{O}\left(a^n\right)\)

Thus O (H) = m .

Since 2 ≤ m ≤ n, H is a proper cyclic subgroup of G.

2) Let G be not a cyclic group.

Then the order of each element of G must be less than mn. So there exists an element, say b in G such that 2 ≤ O (b) < mn. Then H = <b > is a proper subgroup of G

Theorem 10(a). If G is a group of order p,q are prime numbers, then every proper subgroup of G is cyclic.

Proof. Let H be a proper subgroup of G where | G | = pq (p,q are prime numbers)

By Lagrange’s Theorem, | H | divides | G |.

∴ Either | H | = 1 or p or q.

∴| H | = 1 ⇒ H = (e) which is cyclic;

| H | = P (P is Prime) ⇒ H is cyclic and | H | = q {q is prime) ⇒ H is cyclic.

∴ H is a proper subgroup of G which is cyclic. Hence every proper subgroup of G is cyclic.

Theorem 11. If a cyclic group G is generated by an element a of order n, then \( a^m\) is a generator of G iff the greatest common divisor of m and n is 1 i.e. iff m,n are relatively prime i.e. (m,n)=1.

Proof. Let G = <a> such that O (a) = n i.e. \(a^n=e\).

Group G contains exactly n elements.

1)Let m be relatively prime to n. Consider the cyclic subgroup \(\mathbf{H}=\left\langle a^m\right\rangle\) of G.

Clearly H⊆G…(l) . since each integral power of am will be some integral power of a.

Since m and n are relatively prime, there exist two integers x and y such that mx + ny = 1.

∴ \(a=a^1=a^{m x+n y}=a^{n x} \cdot a^{n y}=a^{m x} \cdot\left(a^n\right)^y \cdot=a^{m x} e^y=a^{m x} e=\left(a^m\right)^x\)

∴ Each integral exponent of a will also be some integral exponent of \(a^m\).

∴ G ⊆ H

∴ From (1) and (2), H = G and \(a^m\) is a generator of G.

2)Let \(\mathbf{G}=\left\langle a^m\right\rangle\). Let the greatest common divisor of m and n be d(≠1) i.e. d > 1. Then m/d, n/d just be integers.

Now \(\left(a^m\right)^{n / d}=a^{m n / d}=\left(a^n\right)^{m / d}=e^{m / d}=e\)

∴ \(\mathbf{O}\left(a^m\right)<n\)

(∵ \(\frac{n}{d}<n\))

∴ \(a^m\)cannot be a generator of G because the order of am is not equal to the order of G. So d must be equal to 1. Thus m and n are relatively prime.

Note 1. If G = < a > is a cyclic group of order n, then the total number of generators of G will be equal to the number of integers less than and prime to n.

2. \(\mathbf{Z}_8\) is a cyclic group with 1,3,5,7 as generators.

Note that < 3 > = (3, (3 + 3) mod 8, (3 + 3 + 3) mod 8,……} = (3,6,1,4,7,2,5,0} = \(\mathbf{Z}_8\)

< 2 > = {0,2,4,6} ≠ \(\mathbf{Z}_8\) implies 3 is a generator and 2 is not a generator of \(\mathbf{Z}_8\).

Theorem 12. If G is a finite cyclic group of order n generated by a, then the subgroups of G are precisely the subgroups generated by \( a^m\) where m divides n.

Proof. Since G is a finite cyclic group of order n generated by a, then \(a^m\) generates a cyclic subgroup, say H of G.

Since O(G) = .n, \(a^n=e\) where e is the identity in G.

Since H is a subgroup of G,e ∈ H i.e.\(a^n \in \mathbf{H}\).

If m is the least positive integer such that \(a^m \in \mathbf{H}\) then by division algorithm there exist positive integers q and r such that \(n=m q+r, \quad 0 \leq r<m\).

∴ \(a^n=a^{m q+r}=a^{m q} \cdot a^r=\left(a^m\right)^q \cdot a^r\)

But \(a^m \in \mathbf{H}\) .

∴ \(\left(a^m\right)^q \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{m q} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{-m q} \in \mathbf{H}\).

Now \(a^n \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{-m q} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{n-m q} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^r \in \mathbf{H}\)•

But o < r < m and \(a^r \in \mathbf{H}\) is a contradiction to our assumption that m is the smallest positive integer such that \(a^m \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ r = 0.

∴ n = mq i.e. m divides n and \(a^n=a^{m q}=\left(a^m\right)^q \in \mathbf{H}\) which means that \(a^m\) generates the cyclic subgroup H of G.

Example 10. Find all orders of subgroups of \(Z_6, Z_8, Z_{12}, Z_{60}\)

Solution. \((Z_6,+6)\) is a cyclic group and its subgroups have orders 1, 2, 3, 6 (Theorem.12)

(Proper subgroup of order 2 is ({0,3},+6),

A proper subgroup of order 3 is ({0,2,4},+6)).

⇒ \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_8,+_8\right)\) is a cyclic group and its subgroups have orders 1, 2, 4, 8.

⇒ \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{12},+_{12}\right)\) is a cyclic group and its subgroups have orders 1,2, 3, 4, 6,12.

⇒ \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{60},+_{60}\right)\) is a cyclic group and its subgroups have orders 1,2,3,4,5,6,10,12,15,20,30,60.

Example 11. Write clown all the subgroups of a finite cyclic group G of order 18, the cyclic group being generated by a.

Solution. Let e be the identity in G = < a >.

Now G, {e} are the trivial subgroups of G and generated by a and a18 =e respectively.

The other proper subgroups are precisely the subgroups generated by am where m divides 18. Such m’s are 2, 3, 6, 9. These subgroups are

⇒ \(\left.\left\langle a^2\right\rangle=\left\{a^2, a^4, a^6, a^8, a^{10}, a^{12}, a^{14}, a^{16}, a^{18}=e\right\},<a^3\right\rangle=\left\{a^3, a^6, a^9, a^{12}, a^{15}, a^{18}=e\right\}\)

⇒ \(\left\langle a^6\right\rangle=\left\{a^6, a^{12}, a^{18}=e\right\},\left\langle a^9\right\rangle=\left\{a^9, a^{18}=e\right\}\)

Understanding Cyclic Groups In Abstract Algebra

Theorem 13. The order of a cyclic group is equal to the order of its generator.

Proof. Let G be a cyclic group generated by a i.e. G =<a>

1) Let O(n)= n, a a finite integer.

Then \(e=a^0, a^1, a^2, \ldots \ldots, a^{n-1} \in \mathbf{G}\)

Now we prove that these elements are distinct and these are the only elements of G such that O(G) = n.

Let i,j ( ≤ n – 1) be two non-negative integers such that \(a^i=a^j \text { for } i \neq j\)

Now either i>j or i<j.

Suppose i > j. Then \(a^{i-j}=a^{j-j} \Rightarrow a^{i-j}=a^0=e \text { and } 0<i-j<n\)

But this contradicts the fact that O (a) = n. Hence i=j

∴ \(a^0, a^1, a^2, \ldots \ldots, a^{n-1}\) are all distinct.

Consider any \(a^p \in \mathbf{G}\) where p is any integer.

By Euclid’s Algorithm, we can write p = nq. + r for some integers q and y such that 0 ≤ r < n.

Then \(a^p=a^{n q+r}=\left(a^n\right)^q \cdot a^r=e^q \cdot a^r=e \cdot a^r=a^r\)

But \(a^r\) is one of \(a^0, a^1, \ldots \ldots, a^{n-1}\)

Hence each \(a^p \in \mathbf{G}\)is equal to one of the elements \(a^0, a^1, \ldots \ldots, a^{n-1}\)

i.e. O(G) = n = o{a).

2) LetO(a) be infinite. .

Let m, n be two positive integers such that \(a^m=a^n \text { for } n \neq m\).

Suppose m > n . Then \(a^{m-n}=a^0=e\) ⇒ O(a) is finite.

It is a contradiction to the fact that O (a) is infinite.

∴ n = m i.e. for every pair of unequal integers m and n , \(a^m \neq {a}^n\)

Hence G is of infinite order.

Thus from (1)and(2), the order of a cyclic group is equal to the order of its generator. .

Note. Thus : Let (G,.) be a group and a ∈ G

If a has finite order, say, n, then <a> = \(\left\{e, a, a^2, \ldots \ldots ., a^{n-1}\right\}\) and \(a^i=a^j\) if and only if n divides i-j .

If a has infinite order, then all distinct powers of a are distinct group elements.

Theorem. 14. If G is a cyclic group of order n, then there is a one-to-one correspondence between the subgroups of G and positive divisors of n.

Proof. Let G = <a> be a finite cyclic group of order n.

∴ O(a) = n, a +ve integer. If d (a +ve integer) is a divisor of n, ∃ a +ve integer m such that n = dm.

Now O (a) = n ⇒ \(a^n=e \Rightarrow a^{d m}=e \Rightarrow\left(a^m\right)^d=e \Rightarrow \mathbf{O}\left(a^m\right) \leq d\)

Let \(O (a^m) = s\) where s < d.

Then \((a^m)s\) = e ⇒ \(a^ms = e\) where ms < md i.e. ms < n .

Since 0(a) = n, when ms < n , \(a^ms = e\) is absurd.

∴ i.e. s < d s=d.

∴ \(a^m \in \mathbf{G} \text { where } \mathbf{O}\left(a^m\right)=d\)

Thus \(<a^m>\) is a cyclic subgroup of order d.

Now we show that \(<a^m >\) is a unique cyclic subgroup of G of order d.

We know that every subgroup of a cyclic group is cyclic. If possible suppose that there is another subgroup \(<a^k>\) of G of order d where n = dm.

We shall have to show that \(<a^k> = <a^m>\).

By division algorithm ∃ integers q and r such that k = mq + r where 0 ≤ r < m …(1)

∴ kd = mqd + rd where 0 ≤ rd < md

Now \(a^{k d}=a^{m q d+r d}=a^{m q d} \cdot a^{r d}=\left(a^{m d}\right)^q \cdot a^{r d}=\left(a^n\right)^q \cdot a^{r d}=e^q \cdot a^{r d}=e \cdot a^{r d}\)

⇒ \(a^{k d}=a^{r d}\) …(2)

Since \(<a^k>\) is of order d, \(0(a^k)\) = d

e = \(a^kd\) = e.

⇒ \(a^rd = e\) from (2) which is impossible (∵ rd < md ⇒ rd < m) unless r = 0 .

∴ From (1), k = mq ⇒ \(a^k = a^mq – (a^m)^q\) ⇒ \(a^k \in\left\langle a^m\right\rangle \Rightarrow\langle a\rangle \subseteq\left\langle a^m\right\rangle\)

But number of elements in \(<a^k >\) = number of elements in \(<a^m>\) .

∴ \(\left\langle a^k\right\rangle=\left\langle a^m\right\rangle\)

∴If G is a finite cyclic group of order n, there corresponds a unique subgroup of G of order d for every divisor d of n i.e. there is a 1 – 1 correspondence between the subgroups of G and positive divisors of n.

[∵ a one-on-one mapping is always possible to be defined between the set of subgroups of order d (any +ve divisor of n) and the set of +ve divisors of n]

Classification Of Finite And Infinite Cyclic Groups With Examples

Theorem 15. Every isomorphic image of a cyclic group is again cyclic.

Proof. Let G be a cyclic group generated by a so that \(a^n\) ∈ G from n ∈ Z

Let G’ be its isomorphic image under an isomorphism f.

Now \(a^n \in \mathbf{G} \Rightarrow f\left(a^n\right) \in \mathbf{G}^{\prime}\)

∴ \(f\left(a^n\right)=f(a \cdot a \cdot a, \ldots \ldots, n \text { times })\) when n is a +ve integer

= \(f(a) \cdot f(a) \ldots \ldots, n \text { times }=[f(a)]^n\)

We can prove that \(f\left(a^n\right)=[f(a)]^n\) when n = 0 or a – ve integer

Hence every element \(f\left(a^n\right) \in \mathbf{G}^{\prime}\) can be expressed as \({f(a)}^n\).

∴ f{a) is a generator of G’ implying that G’ is cyclic.

Theorem. 16. Let a he a generator of a cyclic group (G,.) of order n. Then \(a^m\) generates of a cyclic sub-group of (H,.) of (G, .) and O(H)=n/d where d is the H.C.F of n and m.

Proof. am generates a cyclic subgroup (H,.) of (G,.)

Let p be the smallest positive integer such that \((a^m)^p = e\) where e is the identity in H.

Let \(a^m =b\). Let \(b^k \in \mathbf{H} ; k>p\).

Now there exist integers q and r such that k = pq + r,0 ≤ r < p .

∴ \(b^k=b^{p q+r}=b^{p q} \cdot b^r=\left(b^p\right)^q \cdot b^r=e^q \cdot b^r=b^r \text { for } 0 \leq r<p\) .

∴ Any exponent k of b, greater than or equal to p, is reducible to r for 0 ≤ r < p .

∴ H contains p elements given by

∴ \(\mathbf{H} \simeq\left\{b, b^2, \ldots ., b^{p-1}, b^p=e\right\} \text { i.e. } \mathbf{H}=\left\{\left(a^m\right)^1,\left(a^m\right)^2, \ldots .,\left(a^m\right)^p=e\right\}\)

H has p elements, as many elements as the smallest power of \(a^m\) which gives the identity e. Now \(a^pm\) = e if and only if n divides pm since \(a^n\) = e, (G,.) be a cyclic group of order n.

∴ pm/n must be an integer.

Let d be the. H. C. F of n and m. Now \(\frac{p m}{n}=p \cdot \frac{m / d}{n / d}\)

But n/d does not divide m/d.

∴ n/d divides/p. ∴ Least value of p is n/d .

∴ 0 (H) = n/d.

Let | G | = 24 and G be cyclic. If \(a^8 \neq e \text { and } a^{12} \neq e\), show that G = < a > Divisors of 24 are 1,2,3,4,6,8,12, 24.

If | a | = 24 then \(a^2=e \text { and } a^4=\left(a^2\right)^2=e^2=e=a^8\)

Also if |a| = 3 , then \(a^3=e \text { and } a^{12}=\left(a^3\right)^4=e^4=e=a^6\) .

∴ |a|=24 is only acceptable and hence G=<a>.

Theorem 17. A cyclic group of order n has ϕ(n) generators.

Proof. First, we prove Theorem 11.

∴ G = \(<a^m>\) <=> (m,n) = 1 ,

∴ \(<a^m>\) is a generator of G <=> m is a positive integer less than n and relatively prime to n.

⇒ The number of generators of G <=> the number of positive integers that are less than n and relatively prime to n = ϕ(n).

Note. For n = 1, ϕ(1) = 1, and for n > 1 the number of generators ϕ(n) is the number of positive integers less than n and relatively prime to n.

example. a is a generator of a cyclic group G of order 8. Then G = < a > and O (a) = 8 .

Here G = \(\left\{a, a^2, a^3, a^4, a^5, a^6, a^7, a^8\right\}\)

Since 3, 5, 7 are relatively prime to 8 and each is less than \(8, a^3, a^5, a^7\) are the only other generators of G. Also \(a^2, a^4, a^6, a^8\) cannot be the generators of G. Hence G has only 4 generators and they are \(a^1, a^3, a^5,a^7\).

Now < a3 > =\(\left\{a^3, a^6, a^1, a^4, a^7, a^2, a^5, a^8\right\}\), etc.

Cyclic Group Properties And Their Proofs

Example 12. Show that the group (G = \({1,2,3,4,5,6},x_7)\)) is cyclic. Also, write down all its generators.

Solution. Clearly O (G) = 6. If there exists an element a ∈ G such that O (a) = 6, then G will be a cyclic group with generator a.

Since. \(3^1=3,3^2=3 \times_7 3=2,3^3=3^2 \times_7 3=6,3^4=3^3 \times_7 3=4\)

⇒ \(3^5=3^4 \times \times_7=5,3^6=3^5 \times_7 3=1\) , the identity element.

∴ G = \({3, 3^2, 3^3, 3^4, 3^5, 3^6}\) and is cyclic with 3 as a generator.

Since 5 is relatively prime to 6, \(3^5\) i.e. 5 is also a generator of G.

∴ Generators of G are 3 and 5.

Note. If (G, .) is a cyclic group of order n, then the number of generators of G = ϕ(n) = the number of numbers less than n and prime to n.

From theory of numbers, if \(n=p_1^{\alpha_1} \cdot p_2^{\alpha_2} \ldots \ldots p_k^{\alpha_k} \text { where } p_1 \ldots \ldots p_k\) are all primes factors of n, then \(\phi(n)=n\left(1-\frac{1}{p_1}\right) \ldots\left(1-\frac{1}{p_k}\right)\)

⇒ \(\phi(6)=6\left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{3}\right)=2\) i.e. G has 2 generators.

Further, if \(n=p^\alpha\)where p is less than and prime to n, then \(\phi(n)=p^\alpha\left(1-\frac{1}{p}\right)\)

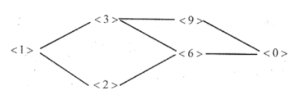

Example 13. Find all the subgroups of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{18},+_{18}\right)\).

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{18},+_{18}\right)\) is a cyclic group with 1 as its generator.

ο \(Z_18\) = {0,1,2,3, ,1.7} and all subgroups are cyclic.

Now all the generators of the group \(Z_18\) are less than 18 and are prime to 18. Thus 1, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, and 17 are all generators of \(Z_18\).

All the subgroups of \(Z_18\) are the subgroups generated by 1,2,3,6,9,18 (Divisors of 18).

This number that corresponds to 18 is 0.

The subgroups are:

Trivial (improper)subgroups- \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{18},+_{18}\right)=\langle 1\rangle,\left(\{0\},+_{18}\right)=\langle 0\rangle\).

proper groups \(\left(\{0,2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16\},+{ }_{18}\right)=\langle 2\rangle\),

⇒ \(\left(\{0,3,6,9,12,15\},++_{18}\right)=\langle 3\rangle\),

⇒ \(\left(\{0,6,12\},+_{18}\right)=\langle 6\rangle,(\{0,9\},+18)=\langle 9\rangle\).

Note.

1.O(<1>)=18, O(<0>)=1,O(<2>)=9,O(<3>)=6,O(<6>)=3,O(<9>)=2.

2. Lattice diagram for \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{18},+_{18}\right)\).

Example 14. Find the number of elements in the cyclic subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{30},+{ }_{30}\right)\) generated by 25 and hence write the subgroup

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{30},+{ }_{30}\right)\) is a cyclic group.

Clearly 1 is a generator of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{30},+{ }_{30}\right)\).

Now \(25 \in \mathbf{Z}_{30} \text { and } 25=1^{25}=(25)(1)\).

Clearly \(\left(1^{25},+_{30}\right)\) is a subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{30},+{ }_{30}\right)\)

The g.c.d. of 30 and 25 is 5.

∴ \(25=1^{25}\) generates a cyclic subgroup of order (30/5) = 6

i.e. ({0,5,10,15,20,25},+30) is the cyclic subgroup generated by 25.

Example 15. Find the no. of elements in the cyclic subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{42},+_{42}\right)\) generated by 30 and hence write the subgroup.

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{42},+_{42}\right)\) is a cyclic group.

Clearly 1 is a generator of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{42},+_{42}\right)\)

Now \(30 \in \mathbf{Z}_{42} \text { and } 30=1^{30}=(30) \text { (1) }\) .

Clearly \(\left(1^{30},+_{42}\right)\) is a subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{42},+_{42}\right)\) .

The g.c.d. of 30 and 42 is 6.

∴ \(30=1^{30}\) generates a cyclic subgroup of order (42/6) = 7

i.e.\(\left(\{0,6,12,18,24,30,36\},+_{42}\right)\) is the cyclic subgroup generated by 30.

Example 16. Find the order of the cyclic subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{60},+_{60}\right)\) generated by 30.

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{60},+_{60}\right)\) is a cyclic group and 1 is a generator of it.

Now \( 30 \in \mathbf{Z}_{60} \text { and } 30=1^{30}=30 \text { (1) }\).

Clearly \(\left(1^{30},+_{60}\right) \text { i.e. }\left(30,++_{60}\right)\) is a subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{60},+_{60}\right)\) .

The g.c.d. of 60 and 30 is 30.

∴ \(30 = l^30\) generates a cyclic subgroup of order (60/30) = 2 .

Example 17. Find the number of generators of cyclic groups of orders 5,6,8,12,15,60.

Solution: O(G)=5, the number of generators of \(\mathbf{G}=\phi(5)=5\left(1-\frac{1}{5}\right)=4\)

O(G)=6, the number of generators of G = ϕ(6)

=\(6\left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{3}\right)=2\) (∵ 2,3 are prime factors of 6)

O(G)=8, the number of generators of G

=\(\phi(8)=8\left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)=4\) (∵ 2 is the only prime factor of 8)

O(G)=12, the number of generators of G

=\(\phi(12)=12\left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{3}\right)=4\) (∵ 2,3 are the only prime factors of 12)

O(G)=15, the number of generators of G = \(\phi(15)=15\left(1-\frac{1}{3}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{5}\right)=8\)

(∵ 3,5 are the only prime factors of 15.)

O(G)=60, the number of generators of

= \(\mathbf{G}=\phi(60)=60\left(1-\frac{1}{2}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{3}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{5}\right)=16\).

(∵ \(60=2^2 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 ; 2,3,5\) are the only prime factors of 60)

Example 18. Show that \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_p,+_p\right)\) has no proper subgroups if p is prime.

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_p,+_p\right)\) is a cyclic group and \(\mathbf{O}\left(\mathbf{Z}_p\right)\) = p where p is prime.

∴ Number of generators of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_p,+_p\right)=p\left(1-\frac{1}{p}\right)\)

∴ All the p -1 elements of \(Z_p\) except the identity element, generate the group \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_p,+_p\right)\). But this is a trivial subgroup.

So \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_p,+_p\right)\) has no proper subgroups.

Example 19. Find all orders of subgroups of the group \(\mathbf{z}_{17}\).

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{17},+_{17}\right)\) is a cyclic group and \(\mathbf{O}\left(\mathbf{Z}_{17}\right)=17\) (17 is prime)

∴ The no. of generators of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{17},+_{17}\right)=17\left(1-\frac{1}{17}\right)=16\)

The 16 elements of \(\mathbf{z}_{17}\) except identity element 0 (which corresponds to 17), generate the group \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{17},+_{17}\right)\) which is of course a trivial subgroup.

Hence \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{17},+_{17}\right)\) has no proper subgroups.

Also {0} is a trivial subgroup. Now \(\mathbf{O}\left(\mathbf{Z}_{17}\right)=17, \mathbf{O}(\{0\})=1\).

Example 20. (1) If p, q be prime numbers, find the number of generators, of the cyclic group \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{p q},+_{p q}\right)\).

Solution.

Given

p, q be prime numbers

The number of generators of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{p q},+_{p q}\right)\)

=\(\phi(p q)=p q\left(1-\frac{1}{p}\right)\left(1-\frac{1}{q}\right)\)(∵ p,q are prime)

(2) If p is a prime number, find the number of generators of the cyclic group \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{p^r},+_{p^r}\right)\) where r is an integer ≥ 1.

Solution. The number of generators = \(\phi\left(p^r\right)=p^r\left(1-\frac{1}{p}\right)=p^{r-1}(p-1)\)

Example 21. G is a group. If a is the only element in G such that \(|\langle a\rangle|=2\), then show that for every x ∈ G, ax = xa.

Solution.

Given

G is a group. If a is the only element in G such that \(|\langle a\rangle|=2\)

a is the only element in group G such that | < a > | = 2.

Let e be the identity in G.

∴ \(a^2=e\).

Also whenever\(b \in \mathbf{G} \Rightarrow b^2=e\), we have b = a

Now for \(x \in \mathbf{G}, x a x^{-1} \in \mathbf{G}\).

∴ In G , \(\left(x a x^{-1}\right)^2=\left(x a x^{-1}\right)\left(x a x^{-1}\right)=x a\left(x^{-1} x\right) a x^{-1}=x \text { e } a x^{-1}\)

=\(x \text { a } a x^{-1}=x a^2 x^{-1}=x \text { e } x^{-1}=x x^{-1}=e\).

∴ \(x a x^{-1}=a \Rightarrow x a x^{-1} x=a x \Rightarrow x a e=a x \Rightarrow x a=a x\).

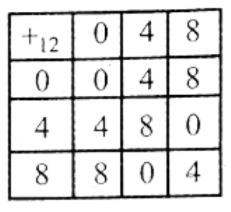

Example. 22. Find all cosets of the subgroup < 4 > of \(\mathbf{Z}_{12}\)

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{12}=\{0,1,2, \ldots ., 11\},+_{12}\right)\)is a cyclic group.

Let the subgroup < 4 > of \(\mathbf{z}_{12}\) be H.

Since <4> = { ,-12,-8,-4,0,4,8,12,….}, \(\left(\mathbf{H}=\{0,4,8\},+_{12}\right)\) is the subgroup of \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{12},+_{12}\right)\) for which all left cosets have to be found out.

Composition Table:

⇒ \(0+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{0,4,8\}, 1+{ }_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{1,5,9\}\)

⇒ \(2+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{2,6,10\}, 3+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{3,7,11\}\)

⇒ \(4+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{4,8,0\}, 5+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{5,9,1\}\)

⇒ \(6+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{6,10,2\}, 7+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{7,11,3\}\)

………………………………………

⇒ \(11+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\{11,3,7\}\)

∴ \(0+_{12} \mathbf{H}=4+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\ldots . .=\{0,4,8\}\)

⇒ \(1+_{12} \mathbf{H}=5+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\ldots \ldots=\{1,5,9\}\)

⇒ \(2+_{12} \mathbf{H}=6+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\ldots . .=\{2,6,10\}\)

⇒ \(3+_{12} \mathbf{H}=7+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\ldots \ldots=\{3,7,11\}\)

Since \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{12},+_{12}\right)\) is abelian, left cosets of H are also right cosets of H.

In \(\mathbf{Z}_{12}\) cosets of H are \(0+_{12} \mathbf{H}, 1++_{12} \mathbf{H}, \ldots ., 11+_{12} \mathbf{H} \text { or } \mathbf{H}++_{12} 0, \mathbf{H}+{ }_{12} 1, \ldots ., \mathbf{H}++_{12} 11\)

Also \(0+_{12} \mathbf{H}=\mathbf{H}, 1+_{12} \mathbf{H}, 2+_{12} \mathbf{H}, 3+_{12} \mathbf{H}\)

Example 23. Find all cosets of the subgroup <18> of \(\mathbf{Z}_{36}\)

Solution. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_{36}=\{0,1,2,3, \ldots \ldots, 35\},+_{36}\right)\) is a finite cyclic abelian group.

The subgroup < 18 > of \(\mathbf{Z}_{36}\) is cyclic and let it be denoted by H.

∴ H = {0,18}.

Here + means +36.

∴ Left cosets of H in \(\mathbf{Z}_{36}\) are

0+ H = {0,18} 18 + H = (18,0}

1+ H = {1,19} 19 +H = {19,1}

2+ H = {2,20} 20 + H = {20,2}

17+ H = {17,35} 35 + H = {35,17}

∴ Distinct left cosets of H in \(\mathbf{Z}_{36}\) are 0+ H,1 + H,….,17+ H and their number is 18

Since\(\mathbf{G}=\left(\mathbf{Z}_{36},+_{36}\right)\) is abelian,

left coset of H in G = right coset of H in G.

Cosets of <18> of \(\mathbf{Z}_{36}\) are 0 + H,1 + H,….,17 + H dr H + 0,H + 1,….,H + 17 .

Example 24. \(S_5\) is the set of all permutations on 5 symbols is a group. Find the index of the cyclic subgroup generated by the permutation (1 2 4) in \(S_5\)

Solution: Let f = (1 2 4).

∴ \(f=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 1 & 5

\end{array}\right)\)

∴ \(f^2=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 1 & 5

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 1 & 5

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

4 & 1 & 3 & 2 & 5

\end{array}\right)\) and

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

4 & 1 & 3 & 2 & 5

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 1 & 5

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5

\end{array}\right)=\mathbf{I}\)

∴ |<f>|=3 and |\(S_5\)| = 5! = 120.

∴ Index of the cyclic subgroup f in \(\mathrm{S}_5=\frac{\left|\mathrm{S}_5\right|}{|\langle f\rangle|}=\frac{120}{3}=40\)

Example 25. If \(\sigma=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 1 & 3 & 4

\end{array}\right), \tau=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 3 & 4 & 1

\end{array}\right)\) are two permutations defind on A={1,2,3,4}, find the cyclic groups generated by σ,τ.

Solution: If n is a least positive integer such that \(f^n=e\) where f is a permutation on A,

then <f>=\(\left\{\mathrm{I}, f, f^2, \ldots \ldots, f^{n-1}\right\}\)

Now \(\sigma^2=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 1 & 3 & 4

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 1 & 3 & 4

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

1 & 2 & 3 & 4

\end{array}\right)=I \Rightarrow\langle\sigma\rangle=\{I, \sigma\}\)

Also \(\tau^2=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 3 & 4 & 1

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 3 & 4 & 1

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

3 & 4 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)\)

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

3 & 4 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 3 & 4 & 1

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

4 & 1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)\) \(\tau^4=\tau^3 \tau=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

4 & 1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

2 & 3 & 4 & 1

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{llll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\

1 & 2 & 3 & 4

\end{array}\right)=I\)

⇒ \(\langle\tau\rangle=\left\{\mathrm{I}, \tau, \tau^2, \tau^3\right\}\)

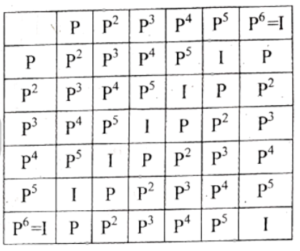

Example 26. If \(\mathrm{S}=\left\{\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{P}^2, \mathrm{P}^3, \mathrm{P}^4, \mathrm{P}^5, \mathrm{P}^6\right\} \text { with } \mathrm{P}=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)\) then by using a multiplication table, prove that S forms an abelian group.

Solution. \(\mathrm{S}=\left\{\mathrm{P}, \mathrm{P}^2, \mathrm{P}^3, \mathrm{P}^4, \mathrm{P}^5, \mathrm{P}^6\right\} \text { with } \mathrm{P}=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)\)

Permutation multiplication is the operation.

⇒ \(P^2=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

4 & 1 & 3 & 2 & 5

\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(P^3=P^2 P=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

4 & 1 & 3 & 2 & 5

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

1 & 2 & 5 & 4 & 3

\end{array}\right)\)

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

1 & 2 & 5 & 4 & 3

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 1 & 5

\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(P^5=P^4 P=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 3 & 1 & 5

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)\)

= \(\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

4 & 1 & 5 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(P^6=P^5 P=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

4 & 1 & 5 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

2 & 4 & 5 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lllll}

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5 \\

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 5

\end{array}\right)=I\)

Clearly, \(P^2 P^3=P^3 P^2, P^3 P^4=P^4 P^3\)

Here \(P^6=I, \quad P^{-1}=P^5, P^5=P^{-1}\)etc. Thus S is an abelian group.

Example 27. Let A = {1,2,3}. Find the cyclic subgroups generated by

⇒ \(P_1=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{array}\right), P_2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right), M_1=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 3 & 2

\end{array}\right) \text { of } S_3\)

Solution: Let A = {1,2,3}. ∴ \(S_3=\left\{e, P_1, P_2, M_1, M_2, M_3\right\}\)

where \(e=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(P_1=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{array}\right), P_2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right), M_1=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 3 & 2

\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(M_2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 1 & 3

\end{array}\right), M_3=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 2 & 1

\end{array}\right)\)(say)

⇒ \(P_1^2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

⇒ \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)=P_2\)

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)=e\)

∴ \(<P_1>=\left\{e, P_1, P_2\right\}\)

⇒ \(P_2^2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{array}\right)=P_1\)

⇒ \(P_2^3=P_2^2 P_2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

2 & 3 & 1

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

3 & 1 & 2

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)=e\)

∴\(\left.<P_2\right\rangle=\left\{e, P_1, P_2\right\}\)

⇒ \(\mathrm{M}_1^2=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 3 & 2

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 3 & 2

\end{array}\right)=\left(\begin{array}{lll}

1 & 2 & 3 \\

1 & 2 & 3

\end{array}\right)=e\)

∴ \(<\mathrm{M}_1>=\left\{e, \mathrm{M}_1\right\}\)

Example 28. If \(f: \mathbf{G} \rightarrow \mathbf{G}^{\prime}\) is isomorphic then the order of an element in G is equal to the order of its image in G’.

Solution. Since f is one – one onto mapping, corresponding to any element a’ ∈ G’ there exists an element a ∈ G. such that f{a) = a’. If e is the identity in G and e’ is the identity in G’ we have f(e) = e’.

Let n be the order of a ∈ G so that \(a^n = e\) where n is the least positive integer.

We have to show that the order of the image f{a) of a is also n.

Now \(a^n=e \Rightarrow f\left(a^n\right)=f(e)=e^{\prime}\)

⇒ f{a .a .a…. n times) = e’ ⇒ f(a).f(a). f (a)…… to n times = e’

⇒ [f(a)]n = e’ => the order of \(f(a) \leq n\) .

Let us suppose that m is the order of f{a) where m < n

so that \([f(a)]^m=e^{\prime}=f(e)\)

i.e. f(a). f(a). f(a)…. m times = f(e).

i.e. f(a. a . a…. m times) = f(e) i.e. \(f\left(a^m\right)=f(e) \Rightarrow a^m=e\)

Since m is less than n, \(a^m = e\) is a contradiction.

Hence there cannot be any other integer m less than n such that \(a^m = e\) .

∴ m = n ⇒ Order of f(a) = Order of a

⇒ Order of the image of an element = order of that element.

Theorem 18. If G is an infinite cyclic group, then G has exactly two generators which are inverses of each other.

Proof. Let G be an infinite cyclic group generated by a.

∴ \(\mathbf{G}=\left\{a^n / n \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\).

Let \(a^m\) be a generator of G.

Since \(a \in \mathbf{G}, \exists\) an integer p such that \(a=\left(a^m\right)^p\).

i.e. \(a^{m p}=a\)

i.e.\(a^{m p} a^{-1}=a \cdot a^{-1}\)

i.e.\(a^{m p-1}=e\)

If mp – 1 > 0 then ∃q = mp – 1 such that \(a^q = e\) implies that G is finite.

But G is infinite.

∴ mp-1=0

i.e. mp = li.e. m = ±1,p = ±1 ,

∴ \(a^1, a^{-1}\) are generators of G.

i.e. G has exactly two generators and one is the inverse of the other in G.

Note. (Z, +) is an infinite cyclic group and it has only two generators 1 and – 1.

Theorem 19. Any infinite cyclic group is isomorphic to the additive group of integers (Z, +)

Proof: Let G be an infinite cyclic group generated by an element \(\mathbf{a}(\in \mathbf{G})\)

Thus 0(a) = 0 or ∞ and \(a^0 = e\) (identity in G)

∴ \(G = \left\{a^n / n \in \mathbf{Z}\right\}\) and all the elements of G are distinct.

Define a mapping \(f: \mathbf{G} \rightarrow \mathbf{Z} \text { such that } f\left(a^n\right)=n, \forall a^n \in \mathbf{G}\)

Let \(a^i, a^j \in \mathbf{G}\) . Let (Z, +) be the additive group of integers.

Now \(f\left(a^i\right)=f\left(a^j\right) \Rightarrow i=j \Rightarrow a^i=a^j\)

∴ f is 1 -1.

Let \(k \in \mathbf{Z}\)

∴ \(a^k \in \mathbf{G} \text { and } f\left(a^k\right)=k\)

∴ f is onto.

Further \(a^i, a^j \in \mathbf{G}\)and\(f\left(a^i a^j\right)=f\left(a^{i+j)}=i+j\right)\)\(f\left(a^i\right)+f\left(a^j\right)\).

∴ f is a homomorphism and hence/is an isomorphism from G to Z.

∴ \(G \cong Z\)

Theorem 20: Every finite cyclic group G of order u is isomorphic to the group of integers addition modulo n, i.e.\(\left(Z_n+{ }_n\right)\)

Proof: Let G be a finite cyclic group of order n generated by an element \( a(\in \mathbf{G})\).

Let e be the identity in G.

∴ \(G = \left\{a^0=e, a, a^2, a^3, \ldots \ldots . ., a^{n-1}\right\}=\left\{a^m / m \text { is an integer and } 0 \leq m<n\right\}\)

⇒ \(\mathbf{Z}_n=\{0,1,2, \ldots . .(n-1)\}\) is the group of integers w.r.t. +n.

Define a mapping \(f: \mathbf{G} \rightarrow \mathbf{Z}_n \text { such that } f\left(a^m\right)=m \forall a^m \in \mathbf{G}\) .

Since \(a^0=e, f(e)=f\left(a^0\right)=0\) where 0 s the identity in \(\left(\mathrm{Z}_n+{ }_n\right)\)

Let \(a^i, a^j \in \mathbf{G}\).

Now \(f\left(a^i\right)=f\left(a^j\right) \Rightarrow i=j \Rightarrow a^i=a^j\)

∴ f is 1 -1.

Let \(k \in \mathbf{Z}_n\)

⇒ \(a^k \in \mathbf{G} \text { and } f\left(a^k\right)=k\)

∴ f is onto.

Let \(a^i, a^j \in \mathbf{G}\). Then \(a^i, a^j \in \mathbf{G}\) and \( f\left(a^i a^j\right)=f\left(a^{l+j}\right)\). By division algorithm, there exist integers q and r.

such that i + j = qn + r, 0 ≤ r < n.

∴ \(a^{i+j}=a^{q n+r}=\left(a^n\right)^q \cdot a^r=e^q a^r=a^r\)

(∵\(a^n=a^0=e\))

∴ \(f\left(a^i a^j\right)=f\left(a^{i+j}\right)=f\left(a^r\right)=r\)

∴ \(f\left(a^i\right)++_n f\left(a^j\right)=r\) by the definition of f.

∴ f is a homomorphism and hence f is an isomorphism from G to \(\mathbf{Z}_n\).

∴ \(\mathbf{G} \cong \mathbf{Z}_n\)