COMPLEX DEFINITION

Any subset of a group G is called a complex of G.

Example. 1. The set of integers is a complex of the group (R,+).

Example. 2. The set of even integers is a complex of the group (Z,+).

Example. 3. The set of odd integers is a complex of the group. (R, +).

Example. 4 The set (1, – 1) is a complex of the multiplicative group G = (1, -1, i,-i)

Multiplication Of Two Complexes.

Definition: If M and N are any two complexes of group G then

MN = (mn ∈ G / m ∈ M, n ∈ N)

Clearly, MN ⊆ G and MN is called the product of the complexes M, N of G.

Theorem 1: The multiplication of complexes of a group G is associative.

Proof: Let M, N, and P be any three complexes in a group G.

Let m ∈ M, n ∈ N, p ∈ P so that m, n, p ∈ G.

We have MN = (mn ∈ G / m ∈ M, n ∈ N} so that

(MN) P = ((mn)p ∈ G / mn ∈ MN, p ∈ P) = (m (n p) ∈ G / m ∈ M, np ∈ NP)

= M (NP) (∵ associativity is true in G )

Note. If HK = KH then we cannot imply that hk = kh for all h ∈ H and for all k ∈ K. What we imply is HK ⊆ KH and KH ⊆ HK.

Definition: If M is a complex in a group G, then we define \(\mathbf{M}^{-1}=\left\{m^{-1} \in \mathbf{G} / m \in \mathbf{M}\right\} \text { i.e. } \mathbf{M}^{-1}\) is the set of all inverses of the elements of M.

Clearly \(\mathbf{M}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{G}\).

Theorem 2: If M, N are any two complexes in group G then \((\mathbf{M N})^{-1}=\mathbf{N}^{-1} \mathbf{M}^{-1}\)

Proof. We have MN = {mn ∈ G / m ∈ M, n ∈ N)

Now \((\mathbf{M N})^{-1}\) = \(\left\{(m n)^{-1} \in \mathbf{G} / m \in \mathbf{M}, n \in \mathbf{N}\right\}\)

= \(\left\{n^{-1} m^{-1} \in \mathbf{G} / m \in \mathbf{M}, n \in \mathbf{N}\right\}=\mathbf{N}^{-1} \mathbf{M}^{-1}\)

Subgroups

Definition: Let (G,.) be a group. Let H be a non-empty subset of G such that (H,.) be a group. Then H is called a subgroup of G.

It is denoted by H ≤ G or G ≥ H. And H < G or G > H we mean H ≤ G, but H ≠ G.

Note: A complex of group G. is only a subset of G but a subgroup of group G is a group. The binary operations in a group and its subgroup are the same.

Example. 1. (Z,.) is a subgroup of (Q,.). Also (Q+,.) ‘is a subgroup of (R+,.)

Example. 2. The additive group of even integers is a subgroup of the additive group of all integers. •

Example. 3. The multiplicative group {1,-1} is a subgroup of the multiplicative group (1,-1, i,-i}.

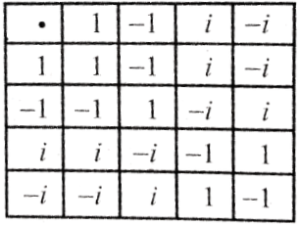

For: G = {1,-1,i,-i} is a group under usual multiplication.

The composition table is:

Here 1 is the identity and \((i)^{-1}=-i,(-i)^{-1}=i,(-1)^{-1}=-1\)

Consider H = {1,-1} which is.a subset of a group (G,.).

Clearly (H,.) is a group.

Here 1 is the identity, \((-1)^{-1}=-1\)

∴ H is a subgroup of G.

Similarly ({1},.),({1,-1,i,-i},.) are subgroups of (G,.).

Example. 4. (N,+) is not a subgroup of the group (Z,+) since identity does not exist in N under +.

Note 1: Every group having at least two elements has at least two subgroups. Suppose e is the identity element in a group G. Then \(\{e\} \subseteq \mathbf{G}\) and we have \(e e=e, e^{-1}=e\), etc.

So {e} is a subgroup of G. Also \(\mathbf{G} \subseteq \mathbf{G}\). So G is also a subgroup of G. These two subgroups {e}, G of G are called trivial or improper subgroups of G. All other subgroups, if they exist, are called non-trivial or proper subgroups of G.

Note 2. A complex of a group need not be a subgroup of the group. But a subgroup of a group is always complex of the group.

Note 3. A complex of a group (G,.) need not be a subgroup w.r.t. the binary operation, but it can be a group w.r.t. another binary operation. For example, the complex \(\left\{3^n, n \in z\right\}\) of the group (Z, +) is not a subgroup of (Z, +) w.r.t. binary operation + whereas the same subset is a group under multiplication.

It is clear that every subgroup of an abelian group is abelian. But for the non-abelian group, it may not be true.

⇒ \(\mathbf{P}_3=\left\{f_1, f_2, f_3, f_4, f_5, f_6\right\}\) set of all bisections on three symbols is a non-abelian group.

But \(\mathbf{A}_3=\left\{f_1, f_5, f_6\right\}\) and H = \(\left\{f_1, f_2\right\}\) an abelian subgroup of P3.

Lattice Diagram. Often it is useful to show the subgroups of a group by a Lattice diagram. In this diagram, we show the larger group near the top of the diagram followed by a line running toward a subgroup of the group.

We give below the Lattice Diagram for the multiplicative group \(\{1,-1, i,-i\}\).

Abstract Algebra Subgroups Notes The Identity And Inverse Of An Element Of A Subgroup H Of A Group G.

Theorem 3: The identity of a subgroup H of a group is the same as the G

Proof. Let a ∈ H and e’ be the identity of H.

Since H is a group, ae’ = a ……………(l)

Let e be the identity in G.

Again a ∈ H => a ∈ G

∴ ae = a ………….(2)

Also e’ ∈ H => e’ ∈ G

From (1) and (2), ae’ = ae => e’= e (using left cancellation law).

Theorem 4: The inverse of any element of a subgroup H of group G is the same as the inverse of that element regarded as an element of group G.

Proof. Let e be the identity in -G.

Since H is a subgroup of G, e is also the identity in H.

Let a ∈ H.

∴ a ∈ G.

Let b be the inverse of a in H and c be the inverse of an in G. Then ab = e and ac = e.

=> ab = ac => b – c (using left cancellation law)

Theorem 5. If H is any subgroup of a group G . then \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\).

Proof. Let H be a subgroup of group G. Let \(h^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}^{-1}\)

By def. of \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}, h \in \mathbf{H}\)

Since H is a subgroup of a group G, \(h^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(h^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}^{-1} \Rightarrow h^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{H}\)

Again \(h \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow h^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow\left(h^{-1}\right)^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}^{-1} \Rightarrow h \in \mathbf{H}^{-1}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H} \subseteq \mathbf{H}^{-1} \text {. Hence } \mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\)

Note. The converse of the above theorem is not true i.e. if H is any complex of a group G such that \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\), then H need not be a subgroup of G.

e.g. H = {-1} is a complex of the multiplicative group G = (1, – 1}.

Since the inverse of -1 is -1, then \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}=\{-1\}\).

But H = {-1} is not a group under multiplication since (-1)(-1) = 1 ∉ H (Closure is not true) i.e. H is not a subgroup of G.

Hence even if \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\) , H is not a subgroup of G.

Theorem 6. If H is any subgroup of group G, then HH = H.

Proof. Let x ∈ HH so that x = \(h_1 \cdot h_2\) where \(h_1 \in \mathbf{H}\) and \(h_2 \in \mathbf{H}\). Since H is a subgroup, \(h_1 h_2 \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ x ∈ H

∴ HH ⊆ H.

Let \(h_3 \in \mathbf{H}\) and e be the identity in H.

Then \(h_3=h_3 e \in \mathbf{H H}\)

∴ H ⊆ HH

∴ HH = H

Abstract Algebra Subgroups Notes Criterion For A Complex To Be A Subgroup

Theorem 7. A non-empty complex H of a group G is a subgroup of G if and only if

(1) \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H}\)

(2) \(a \in \boldsymbol{H}, a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

Proof. The conditions are necessary.

Let H be a subgroup of the group G.

• To prove that (1), (2) are true

∴ H is a group.

∴ By closure axiom a, b ∈ H => ab ∈ H and by inverse axiom \(a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

The conditions are sufficient.

Let (1) and (2) be true.

To prove that H is a subgroup of G.

1. By (1) closure axiom is true in H.

2. The elements of H are also elements of G. Since G is a group, the composition ‘ in G is associative and hence the composition in H is associative.

3. Since H is non-empty, let a ∈ H.

∴ By (2) \(a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H}, a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\).

=> e ∈ H (∵ \(a a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a a^{-1} \in \mathbf{G} \Rightarrow a a^{-1}=e\) where e is the identity in G ).

=> e is the identity in H.

4. Since we have \(a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\) and \(a a^{-1}=e\) evety element of H possess inverse in H. Hence H itself is a group for the composition in G. So H is a subgroup of G.

Note 1. If the operation in G is +, then the conditions in the above theorem can be stated as follows :

a, \( b \in \mathrm{H} \Rightarrow a+b \in \mathrm{H}\) , (ii) \(a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow-a \in \mathbf{H}\)

2. It is called a Two-step subgroup Test.

Theorem 8. H is a non-empty complex of a group G. The necessary and sufficient condition for H to be a subgroup of G is \(a, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\) where \(b^{-1}\) is the inverse of. b in G.

Proof.

Given

H is a non-empty complex of a group G. The necessary and sufficient condition for H to be a subgroup of G is \(a, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\) where \(b^{-1}\) is the inverse of. b in G.

The condition is necessary.

Since H is a group by itself, \(b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a \in \mathbf{H}, b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\) (by closure axiom).

The condition is sufficient.

1. Since \(\mathbf{H} \neq \phi, \text { let } a \in \mathbf{H}\)

By hyp. \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

a \(\in \mathbf{H}, a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a a^{-1} \in \mathbf{G}\)

But in G, \(a \in \mathbf{G} \Rightarrow a a^{-1}=e\), e is the identity in G.

∴ e ∈ H

2. We have \(e \in \mathbf{H}, a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow e a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

3. \(b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a, b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a\left(b^{-1}\right)^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

=> \(a b \in \mathbf{H}\)

4. Since all the elements of H are in G and since the composition is associative in

G, the composition is associative in H.

∴ H is a group for the composition in G and hence H is a subgroup of G.

Note 1. If the operation in G is +, then the condition in the above theorem can be stated as follows :

a\(\in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a-b \in \mathbf{H}\)

2. The above theorem can be used to prove that a certain non-empty subset of a given group is a subgroup of the group. It is called the One-step subgroup Test.

Theorem 9. A necessary and sufficient condition for a non-empty complex H of a group G to be a subgroup of G is that \(\).

Proof. The condition is necessary.

Let H be a subgroup of G.

Let \(a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H H}^{-1}\) so that a ∈ H, b ∈ H

Since H is a group we have \(b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\).

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\) , (By closure axiom)

∴ \(\mathbf{H H}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{H}\)

The condition is sufficient.

Let \(\mathrm{HH}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{H}\). Let a, b ∈H.

∴ \(a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H H}^{-1}\)

Since \(\mathbf{H H}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{H}, a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ H is a subgroup of G.

Theorem 10. A necessary and sufficient condition for a non-empty subset H of a group G to be a subgroup of G is that \(\mathbf{H H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\).

Proof. The condition is necessary.

Let H be a subgroup of G. Then we have \(\mathrm{HH}^{-1} \subseteq \mathrm{H}\).

Let e be the identity in G.

∴ e is the identity in H.

Let h ∈ H

∴ \(h=h e=h e^{-1} \in \mathbf{H H}^{-1}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H} \subseteq \mathbf{H H}^{-1}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H H}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{H}\)

The condition is sufficient.

Let \(\mathbf{H} \mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\).

∴ \(\mathbf{H H}^{-1} \subseteq \mathbf{H}\)

∴ H is a subgroup of G.

Theorem 11. The necessary and sufficient condition for a finite complex H of a group G is \(a, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H}\)

OR

Prove that a non-empty finite subset of a group which is closed under multiplication is a subgroup of G.

Proof. The condition is necessary.

H be a subgroup of G. By closure axiom, \(\).

The condition is sufficient.

Let \(a, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H}\) (∵ H ≠ ∅)

Let a ∈ H.

By hyp. we have \(a \in \mathbf{H}, a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a \cdot a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^2 \in \mathbf{H}\)

Again \(a^2 \in \mathbf{H}, a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^2, a \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a^3 \in \mathbf{H}\)

By induction, we can prove that \(a^n \in \mathbf{H}\) where n is any positive integer.

Thus all the elements \(a, a^2, a^3, \ldots, a^n, \ldots\) belong to H and they are infinite in number.

But H is a finite subset of G.

But H is a finite subset of G.

Therefore, there must be repetitions in the collection of elements.

Let \(a^r=a^s\) for some positive integers r and s such that r > s

∴ \(a^r \cdot a^{-s}=a^s \cdot a^{-s}=a^{s-s}=a^0=e\) where e is the identity in G.

Since r – s is a positive integer, \(a^{r-s} \in \mathbf{H}^{\prime} \Rightarrow e \in \mathbf{H}\)

∴ \(e=a^0 \in \mathbf{H}\).

Now r > s => r – s ≥ 1

∴ r – s – 1 ≥ 0 and hence \(a^{r-s-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

Also \(a^{r-s-1} a=a^{r-s}=e=a \cdot a^{r-s-1}\)

∴ We have for \(a \in \mathbf{H}, a^{r-s-1} \in \mathbf{H}\) as the inverse of a.

Thus each element of H is invertible.

Since all the elements of H are elements of G, associativity is satisfied.

H is a group for the composition in G and hence H is a subgroup of G.

Cor. A finite non-empty subset H of a group G is also a subgroup of G if and only if HH = H.

e.g. \(\left(\mathbf{Z}_6,+_6\right)\) is a group and \(\left(\mathbf{H}=\{0,2,4\},+_6\right)\) is a subgroup of it.

For: \(\mathbf{H} \subset \mathbf{Z}_6\). Also \(0+_6 0=0,0+_6 2=2,0+_6 4=4,2+_6 4=0,4+_6 4=2\) etc.

So \(a, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a+_6 b \in \mathbf{H}\)

Note. The criterion given in the above theorem is valid only for finite subsets of a group G. It is not valid for an infinite subset of an infinite group G.

e.g. (Z, +) is a group. Let N be the set of all positive integers.

N ⊂ Z. Also (N, +) is not a group even though a, b ∈ N => a + b ∈ N.

∴ (N,+) is not a subgroup of (Z,+). Hence the above theorem is not satisfied.

Theorem 12. A non-empty subset H of a finite group G is a subgroup if \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H}\)

OR

A necessary and sufficient condition for a complex H of a finite group G to be a subgroup is that \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H} .\).

Proof. The condition is necessary.

Let H be a subgroup of a finite group G.

Then H is closed w.r.t. the composition in G.

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H}\)

The condition is sufficient.

H is a non-empty subset (complex of G ) of a finite group G such that

a \(\in \mathbf{H}, b \in \mathbf{H} \Rightarrow a b \in \mathbf{H}\)

Now we have to prove that H is a subgroup of G.

Associativity. Since H is a subset of G, all the elements of H are the elements of G and hence associativity is true in H w.r.t. the composition in G.

Existence of identity. Let a ∈ H.

a ∈ G. Since G is finite and since every element of a finite group is of finite order, it follows that the order of a is finite.

Let 0 (a) = n

∴ \(a^n=e\) where e is the identity in G.

By closure law in H, we have \(a^2, a^3, \ldots, a^n, \ldots \in \mathbf{H}\). …………..(1)

Since \(a^n=e=a^0\), we have \(a^0=e \in \mathbf{H}\) i.e. identity exists in H.

Existence of inverse. Let a ∈ H Here \(e=a^n=a^0\).

∴ a ∈ G and 0(a) = n => n is the least positive integer such that

=> (n – 1) > 0. \(a^n=e\)

By (1), \(a^{n-1} \in \mathbf{H}\).

Now in G, \(a^{n-1} a=a^n=a a^{n-1}\).

=> \(a^{n-1} a=a a^{n-1}=e\) true in H .

=> \(a^{-1}=a^{n-1}\)

=> Every element of H is invertible.

=> H is a group and hence a subgroup of G.

Abstract Algebra Subgroups Notes Criterion For The Product Of Two Subgroups To Be A Subgroup

Theorem 13. If H and K are two subgroups of a group G, then HK is a subgroup of G iff HK = KH.

Proof. Let H, K be any two subgroups of G.

1st part. Let HK = KH. To prove that HK is a subgroup of G.

So it is sufficient to prove that \((\mathbf{H K})(\mathbf{H K})^{-1}=\mathbf{H K}\)

⇒ \((\mathbf{H K})(\mathbf{H K})^{-1}\)

= \((\mathbf{H K})\left(\mathbf{K}^{-1} \mathbf{H}^{-1}\right)\)(Theorem 2.)

= \(\mathbf{H}\left(\mathbf{K K}^{-1}\right) \mathbf{H}^{-1}\) (∵ Complex multiplication is associative).

= \(\mathbf{H}(\mathbf{K}) \mathbf{H}^{-1}\) (Theorem 10) = \((\mathbf{H K}) \mathbf{H}^{-1}\) (Theorem 1) .

= \(\text { (KH) } \mathbf{H}^{-1}\) (Hyp.) = \(\mathbf{K}\left(\mathbf{H H}^{-1}\right)=\mathbf{K H}=\mathbf{H K}\).

HK = KH => HK is a subgroup of G.

2nd part. Let HK be a subgroup of group G.

∴ \((\mathrm{HK})^{-1}=\mathrm{HK} \Rightarrow \mathrm{K}^{-1} \mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathrm{HK} \Rightarrow \mathrm{KH}=\mathrm{HK}\)

(∵ K is a subgroup, \(\mathbf{K}^{-1}=\mathbf{K}\) and H is a subgroup, \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}=\mathbf{H}\))

Cor. If H, K are subgroups of an abelian group G, then HK is a subgroup of G.

For: Since G is abelian, HK = KH. By the above theorem, HK is a subgroup of G.

Abstract Algebra Subgroups Notes Solved Problems

Example.1: If Z is the additive group of integers, then prove that the set of all multiples of integers by a fixed integer m is a subgroup of Z.

Solution:

Given

Z is the additive group of integers

We have Z = { ….,3,-2,-1, 0,1,2,3,…}

Let H = {…,- 3m, – 2m, – m, 0, m, 2m, 3m,…} = mz

where m is a fixed integer.

Let a = rm, b = sm be any two elements of H where r, s are integers.

Then a – b = rm – sm = (r – s) m – pm where p is an integer

=> a – b ∈ H.

∴ a, b ∈ H => a – b ∈ H.

∴ H is a subgroup of Z.

Example. 2: Prove that in the dihedral group of order 8, denoted by \(\mathbf{D}_4\), the subset \(\mathbf{H}=\left\{r_{360}, r_{180}, x, y\right\}\) is subgroup of \(\mathbf{D}_4\).

Solution: We can observe from the composition table of \(\mathbf{D}_4\).

(1) Closure is obvious.

(2) Associativity is evident since the composition of maps is associative

(3) The identity element of H is \(r_{360}\).

(4) Each element of H is inverse of itself. I

∴ H is a group. Here H is a subgroup of \(\mathbf{D}_4\).

Example. 3 : \(\mathbf{P}_3\) is a non-abelian group of order 6. \(\mathbf{A}_3\) is a subgroup of \(\mathbf{P}_3\). Also \(\mathbf{A}_3\) is an abelian subgroup of \(\mathbf{P}_3\).

Example. 4: We have \(\mathbf{G}=\left\{r_0, r_1, r_2, f_1, f_2, f_3\right\}\) the set of all symmetries of cm Unilateral triangle, as a non-abelian group.

Consider \(\mathrm{H}=\left\{r_0, r_1, r_2\right\}\) . We can see from the composition table that H is a subgroup of G. Also H is abelian. Hence a non-abelian group can have an abelian subgroup.

Example. 5: S, the set of all ordered pairs (a,b) of real numbers for which a ≠ 0 w.r.t the operation x defined by (a, b) x (c, d) = (ac, be + d) is a non-abelian group.

Let H = {(1, b) | b ∈ R} be a subset of S. Show that H is a subgroup of the group (S, x).

Solution:

Given

S the set of all ordered pairs (a,b) of real numbers for which a ≠ 0 w.r.t the operation x defined by (a, b) x (c, d) = (ac, be + d) is a non-abelian group.

Let H = {(1, b) | b ∈ R} be a subset of S.

Identity in S is (1, 0). Clearly’ (1, 0) ∈ H.

The inverse of (a,b) in S is \(\left(\frac{1}{a},-\frac{b}{a}\right)\) (∵ a ≠ 0)

The inverse of (1, c) in S is \(\left(\frac{1}{1},-\frac{c}{1}\right)\) i.e (1, -c)

Clearly (1 ,c) ∈ H. Let (1,b) ∈ H.

∴ \((1, b)(1, c)^{-1}=(1, b) \times(1,-c)=(1,1, b .1-c)=(1, b-c) \in \mathbf{H} \text { since } b-c \in \mathbf{R}\)

∴ \((1, b),(1, c) \in \mathrm{H} \Rightarrow(1, b) \times(1, c)^{-1} \in \mathrm{H}\)

∴ H is a subgroup of (S, x).

Note. \(\)

H is an abelian subgroup of the non-abelian group (S, x).

Hence a non-abelian group can have an abelian subgroup.

UNION AND INTERSECTION OF SUBGROUPS

Theorem 14. If \(\mathrm{H}_1 \text { and } \mathrm{H}_2\) are two subgroups of a group G then \(\mathrm{H}_1 \cap \mathrm{H}_2\), is also a subgroup of G.

(OR)

If H and K are subgroups of a group G show that \(\mathbf{H} \cap \mathbf{K}\) is also a subgroup of G. )

Proof. Let \(\mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } \mathbf{H}_2\) be two subgroups of G.

Let e be the identity in G.

∴ \(e \in \mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } e \in \mathbf{H}_2 \Rightarrow e \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2 \neq \phi\)

Let \(a \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2, b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\)

∴ \(a \in \mathbf{H}_1, a \in \mathbf{H}_2 \text { and } b \in \mathbf{H}_1, b \in \mathbf{H}_2\)

Since \(\mathbf{H}_1\) is a subgroup, \(a \in \mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}\)

Similarly \(a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}_2\).

∴ \(a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\)

Thus we have \(a \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2, b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2 \Rightarrow a b^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\).

∴ \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\) is a subgroup of G.

Note 1. The intersection of an arbitrary family of subgroups of a group is a subgroup of the group i.e. if \(\left\{\mathbf{H}_i / i \in \Delta\right\}\) is any set of subgroups of a group G, then \(\bigcap_{i \in \Delta} \mathbf{H}_i\) is a subgroup of G.

2. \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\) is the largest subgroup of G contained in \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\) is the subgroup contained in \(\mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } \mathbf{H}_2\) and is the subgroup that contains every subgroup of G contained in both \(\mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } \mathbf{H}_2\).

3. The union of two subgroups of a group need not be a subgroup of the group.

e.g. Let (Z,+) be the group of all integers.

Let \(\mathbf{H}_1=\{\ldots-6,-4,-2,0,2,4 \ldots\}=2 \mathbf{Z}\) and

⇒ \(\mathbf{H}_2=\{\ldots-12,-9,-6,-3,0,3,6,9 \ldots\}=3 \mathbf{Z}\) be two subgroups of Z.

We have \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2=\{\ldots,-12,-9,-6,-4,-3,-2,0,2,3,4,6,9 \ldots\}\).

Since \(4 \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2, 3 \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) does not imply \(4+3 \in

\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2, \mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) is not closed under +.

∴ \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) is not a subgroup of (Z,+).

So the intersection of two subgroups of a group is a subgroup of the group whereas the union of two subgroups of a group need not be a subgroup of the group.

Thus we conclude: An arbitrary intersection of subgroups of a group G is a subgroup but the union of subgroups need not be a subgroup.

Theorem 15. The union of two subgroups of a group is a subgroup if one is contained in the other.

(OR)

If H and K are subgroups of a group Q then show that H ∪ K is a subgroup if either H ⊆ K or K ⊆ H

Proof. Let \(\mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } \mathbf{H}_2\) be two subgroups of a group (G,.)

To prove that \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) is a subgroup ⇔ \(\mathbf{H}_1 \subseteq \mathbf{H}_2 \text { or } \mathbf{H}_2 \subseteq \mathbf{H}_1\).

The condition is necessary.

Let \(\mathbf{H}_1 \subseteq \mathbf{H}_2\)

∴ \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2=\mathbf{H}_2\)

Since \(\mathbf{H}_2\) is a subgroup of G, \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) is a subgroup of G.

Similarly, \(\mathbf{H}_2 \subseteq \mathbf{H}_1\) => \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) is a subgroup of G.

The condition is sufficient.

Let \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) be a subgroup of G.

We prove that \(\mathbf{H}_1 \subseteq \mathbf{H}_2 \text { or } \mathbf{H}_2 \subseteq \mathbf{H}_1\)

Suppose that \(\mathbf{H}_1 \not \subset \mathbf{H}_2 \text { and } \mathbf{H}_2 \not \subset \mathbf{H}_1\)

Since \(\mathbf{H}_1 \not \subset \mathbf{H}_2, \exists a \in \mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } a \notin \mathbf{H}_2\).

Again \(\mathrm{H}_2 \subset \mathrm{H}_1 \Rightarrow 3 b \in \mathrm{H}_2 \text { and } b \notin \mathrm{H}_1\).

From (1) and (2) we have that \(a \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2 \text { and } b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\).

Since \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cup \mathbf{H}_2\) is a subgroup, we have \(a b \in \mathrm{H}_1 \cup \mathrm{H}_2\).

∴ \(a b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \text { or } a b \in \mathbf{H}_2 \text { or } a b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\).

Suppose \(a b \in \mathrm{H}_1\).

Since \(\mathrm{H}_1\) is a subgroup, \(a \in \mathrm{H}_1 \text { and } a b \in \mathrm{H}_1\)

=> \(a^{-1} \in \mathbf{H}_1 \text { and } a b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \Rightarrow a^{-1}(a b) \in \mathbf{H}_1\)

=> \(\left(a^{-1} a\right) b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \Rightarrow c b \in \mathbf{H}_1 \Rightarrow b \in \mathbf{H}_1\) which is absurd by (2).

∴ ab ∉ \(\mathbf{H}_1\)

Similarly, we can show that ab ∉ \(\mathrm{H}_2\).

∴ ab∉ \(\mathbf{H}_1 \cap \mathbf{H}_2\)

∴ ab ∉ \(\mathrm{H}_1 \cup \mathrm{H}_2\) which is a contradiction that \(\mathrm{H}_1 \cup \mathrm{H}_2\) is a group.

∴ we must have \(\mathrm{H}_1 \subseteq \mathrm{H}_2 \text { or } \mathrm{H}_2 \subseteq \mathrm{H}_1\).

Note. \(\left(Z_{16,}+16\right)\) is a group. \(\mathrm{S}=\{0,8\}, \mathrm{T}=\{0,4,8,12\}\) under \(+_{16}\) are two groups. Clearly, they are subgroups of \(Z_{16}\). Since S ∪ T = {0,4,8,12} = T, we have \(\left(S \cup T_{,}+{ }_{16}\right)\)

as a subgroup of \(Z_{16}\). Observe that \(S \subset T\) i.e. S is contained in T.

Example.6. Prove that a set of all multiples of 3 is a subgroup of the group of integers under addition.

Solution: Consider \(3 Z=\{3 n / n \in Z\}\)

3\(Z \neq \phi\) and 3Z is a subset of Z.

Let \(3 m, 3 n \in 3 Z \Rightarrow m, n \in Z\)

3\(m-3 n=3(m-n) \in 3 Z\)

∴ (3Z,+) is a subgroup of (Z, +) (using Th.8)

Example. 7. G & a group of non-zero real numbers under multiplication. Prove that

(1) \(\mathbf{H}=\{x \in \mathbf{G} / x=1 \text { or } x \text { is irrational }\}\)

(2) \(\mathbf{K}=\{x \in \mathbf{G} / x \geq 1\}\) are not subgroups of G

Solution: (1) \(\sqrt{2}, \sqrt{2} \in H\) but \(\sqrt{2} \cdot \sqrt{2}=2 z \mathrm{H}\).

So H is not a subgroup even though H ⊂ G.

(2) 1 is the identity in G and K ⊂ G.

2 ∈ K but \(2^{-1}=(1 / 2) \notin K\) . So K is not a subgroup.

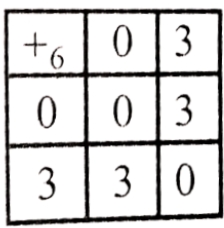

Example. 8. \(\left(Z_6=\{0,1,2,3,4,5\}_{,}+6\right)\) is a group. Prove that S = [0,2,4}, T = {0,3} are subgroups of \(Z_6\) and S ∪ T, not a subgroup of \(\mathrm{z}_6\).

Solution: S = {0,2,4}, T = {0,3} are subsets of \(\mathrm{z}_6\). and From the tables, 0 is the identity

(1) \(0^{-1}=0,2^{-1}=4,4^{-1}=2\)

(2)\(0^{-1}=0,3^{-1}=3\)

Clearly \(\left(\mathbf{S},+_6\right),\left(\mathbf{T},+_6\right)\) are subgroups of \(\mathrm{z}_6\).

Now S ∪ T = {0,2,3,4} is not a subgroup of \(\mathrm{z}_6\) as \(1,5 \notin \mathbf{S} \cup \mathbf{T}\)