Rings, Integral Domains And Fields

Examples Of Rings In Mathematics With Solutions

The ring is the second algebraic system of the subject of Modern Algebra. The abstract concept of rings has its origin from the set of integers. Even though integers, real numbers, integers modulo − n, and Matrices are endowed with two binary operations, when dealt them in Groups we have considered only one binary operation ignoring the other.

The concept of Ring will take into account both addition and multiplication. The algebra of rings will follow the pattern already laid out for groups.

Definition. (Ring.) Let R be a non-empty set and +, · be two binary operations in R. (R, +, ·) is said to be a ring if, for a,b,c ∈ R;

R1 · a + b = b + a

R2· (a + b) + c = a + (b + c)

R3. there exists 0 ∈ R such that a + 0 = a for a ∈ R.

R4. there exists −a ∈ R such that a + (−a) = 0 for a ∈ R.

R5· (a · b) · c = a · (b · c) and

R6· a · (b + c) = a · b + a · c and (b + c) · a = b · a + c · a.

Note

1. The operation ’+’ is called the addition and the operation ’ · ’ is called the multiplication in the ring (R, +, •).

2. The ring (R, +, ·) is also called the ring R.

3. We write a.b as ab.

4. The properties R1,R2,R3,R4 merely state that (R, +) is a commutative group. Thus (R, +) is called the additive group of the ring R.

5. The identity element ’ 0 ’ in (R, +) is called the zero of the ring R. The zero of a ring should not be confused with the zero of the numbers.

6. By R3, 0 + 0 = 0 for 0 ∈ R.

7. The properties R5, and R6 may be respectively called the Associative and Distributive laws.

In view of Note (4) and Note (7) a ring may also be defined as follows:

Definition. (Ring.) Le t.R be a non-empty set and +, · b e two binary operations in R.(R, +, ·) is said to be a ring, if

(1) (R, +) is a commutative group,

(2) (R, ·) is a semigroup and

(3) Distributive laws hold.

Definition. (Unity Element.) In a ring (R, +, ·) if there exists 1 ∈ R such that a.1 = 1. a = a for every a ∈ R then we say that R is a ring with unity element or identity element.

Note 1. If R is a ring with identity element, by R4, we have −1 ∈ R so that

1 + (−1) = 0.

2. A ring with unity element contains at least two elements 0 and 1 if R 6= {0}.

Definition. In a ring (R, +, ·) if a.b = b.a for a, b ∈ R then we say that R is a commutative ring.

Imp. A ring R (1) need not be commutative under multiplication and (2) need not have an identity (unity) element under multiplication, unless or otherwise stated.

Example. 1. Let R = {0} and +, · be the operations defined by 0 + 0 = 0 and 0 · 0 = 0. Then (R, +, ·) is clearly a ring called the Null ring or Zero ring.

Integral Domains Definition And Examples Step-By-Step

Example 2. The set Z of integers w.r.t. usual addition and multiplication is a commutative ring with unity element.

For (1) (Z, +) is a commutative group (2) Multiplication is associative in Z and (3) Multiplication is distributive over addition.

Example. 3. The set N of natural numbers is not a ring w.r.t. usual addition and multiplication, because, (N, +) is not a group.

Example. 4. The sets Q, R, and C are rings under the usual addition and multiplication of numbers.

Example 5. The set of integers mod under the addition and multiplication mode is a ring.

Example. 6. The set of irrational numbers under addition and multiplication is not a ring as there is no zero element.

Let (R, +, ·) be a commutative ring with unity element. Then (R, +) is a commutative group and (R, ·) is a semi-group with identity. element 1. So we have the following results which are obvious from the theory of groups.

1. The zero element of R is unique and a + 0 = a for every element ’ a ’ in R.

2. For a ∈ R the additive inverse −a ∈ R is unique and a + (−a) = 0.

3. The identity element 1 ∈ R is unique and a · 1 = 1.a = a for every a ∈ R.

4. For a ∈ R, −(−a) = a. 5. For 0 ∈ R, −0 = 0. 6. For a, b ∈ R, −(a + b) = −a − b.

5. For a, b, c ∈ R, a + b = a + c ⇒ b = c and b + a = c + a ⇒ b = c

6. For a, b, x ∈ R, the equations a+x = b and x+a = b have unique solutions.

7. For 1 ∈ R, the identity element, −(−1) = 1.

8. For a, b1, b2, . . . . . . .bn ∈ R, from R6, we have a (b1 + b2 + . . . .. + bn) = ab1 + ab2 + . . . + abn and (b1 + b2 + . . . .. + bn) a = b1a + b2a + . . . . + bna.

Notation. 1. If R is a ring and a, b ∈ R then a + (−b) ∈ R, a + (−b) is written as a − b.

9. If R is a ring and a ∈ R then a + a ∈ R and a + a is written as 2a.

10. If R is a ring and a ∈ R then a · a ∈ R and a · a is written as a2.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Some Basic Properties Of Rings

Theorem 1. If R is a ring and 0, a, b ∈ R, then

- 0a = a0 = 0,

- a(−b) = (−a)b = −(ab)

- (−a)(−b) = ab

- a(b − c) = ab − ac. )

Proof. (1) 0a = (0 + 0)a ⇒ 0 + 0a = 0a + 0a (By R3, R6)

∴ 0 = 0a (By right cancellation law of (R, +) )

Similarly, we can prove that a0 = 0. Hence 0a = a0 = 0

(2) To prove that a(−b) = −(ab) we have to show that a(−b) + (ab) = 0.

a(−b) + ab = a{(−b) + b} = a0 = 0 ( By R6, R4) ⇒ a(−b) = −(ab)

Similarly, we can prove that (−a)b = −(ab).

Hence, a(−b) = (−a)b =−(ab).

(3) (−a)(−b) = −{(−a)b} = −{−(ab)} = ab ( by (2 ))[ ∵ (R, +) is a group ]

(4) a(b − c) = a[b + (−c)] = ab + a(−c) = ab − ac (By R6 ) [By theorem (1), (2)]

Similarly, we can prove that (b − c)a = ba − ca.

Solved Problems On Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields

Theorem. 2. If (R, +, ·) is a ring with unity then this unity 1 is the only multiplicative identity.

Proof. Suppose that there exist 1, 10 ∈ R such that 1.x = x.1 = x and 10 · x = x · 10 = x∀x ∈ R

Regarding 1 as identity, 1.10 = 10. Regarding 10 as identity, 1.10 = 1

Thus 10 = 1.10 = 1. ∴ 1 is the only multiplicative identity.

Theorem, 3. If R is a ring with unity element 1 and a ∈ R then

- (−1)a = −a

- (−1)(−1) = 1

Proof. (1) (−1)a+a = (−1)a+1a = {(−1)+1}a = 0a = 0 ( ∵ a = 1a, R6, R4)

∴ (−1)a = −a

(2) For a ∈ R we have (−1)a = −a. . Taking a = −1, (−1)(−1) = −(−1) =1

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Boolean Ring

Definition. In a ring R if a2 = a∀a ∈ R then R is called a Boolean ring.

Theorem 1. If R is a Boolean ring then (1) a + a = 0∀a ∈ R (2) a + b = 0 ⇒ a = b and (3) R is commutative under multiplication. Or, Every Boolean ring is abelian.

Proof. (1) a ∈ R ⇒ a + a ∈ R.

Since a2 = a∀a ∈ R, we have (a + a)2 = a + a ⇒ (a + a)(a + a) = a + a ⇒ a(a + a) + a(a + a) = a + a ⇒ a2 + a2 + a2 + a2 = a + a (By R6) ⇒

(a+a)+(a+a) = a+a ( ∵ R is Boolean ) ⇒ (a+a)+(a+a) = (a+a)+0 (By R3 ) ⇒ a + a = 0 [By left cancellation law of group (R, +)]

(2) For a, b ∈ R, a + b = 0 ⇒ a + b = a + a ⇒ b = a [By (1)]

(3) a, b ∈ R ⇒ a + b˙ ∈ R ⇒ (a + b)2 = a + b

(∵ R is Boolean) ⇒ (a + b)(a + b) = a + b ⇒ a(a + b) + b(a + b) = a + b (By R6) ⇒ a2 + ab + ba + b2 = a + b (By R6 ) ⇒ (a + ab) + (ba + b) =

a + b. (∵ R is Boolean) ⇒ (a + b) + (ab + ba) = a + b [ ∵ (R, +) is a group ] ⇒ (a + b) + (ab + ba) = (a + b) + 0 ⇒ ab + ba = 0 ⇒ ab = ba (By (2))

Rings, Integral Domains And Fields Solved Problems

Example. 1. If R is a ring with identity element 1 and 1 = 0 then R = {0}.

Solution. x ∈ R ⇒ x = 1x ⇒ x = 0x ⇒ x = 0

[By Theorem 1(1)]

∴ R = {0}

Thus a ring R with unity has at least two elements if R6 = {0}.

Rings And Their Properties With Detailed Examples

Example. 2. Prove that the set of even integers is a ring, commutative without unity under the usual addition and multiplication of integers.

Solution. Let R = the set of even integers. Then R = {2x | x ∈ Z}.

a, b, c ∈ R ⇒ a = 2m, b = 2n, c = 2p where m, n, p ∈ Z.

(R, +) is a commutative group. (see ex. in groups)

a · b = (2m)(2n) = 2l where l = 2mn ∈ Z

∴ Multiplication ( · of integers is a binary operation in R.

(a · b) · c = (2m · 2n) · 2p = 8mnp and a · (b · c) = 2m · (−2n · 2p) = 8mnp

∴ (a.b).c = a.(b.c) ⇒ Multiplication (•) is associative in R.

a. (b + c) = 2m(2n + 2p) = 2m · 2n + 2m · 2p = a · b + a · c

Similarly, (b + c) · a = b · a + c · a

∴ Distributive laws hold in R. Hence (R, +, ·) is a ring.

Since ’ 1 ’ is not an even integer; 1 ∈/ R and hence R has no unity element.

Example. 3. (R, +) is an abelian group. Show that (R, +, ·) is a ring if multiplication (·) is defined as a.b=0 ∀a, b ∈ R.

Solution. To prove that (R, +, ·) is a ring we have to show that (R, ·) is semigroup and distributive laws hold.

∀a, b ∈ R, a.b = 0 where 0 ∈ R is the zero element in the group.

∴ multiplication ‘0 ’ is a binary operation in R.

Let a, b, c ∈ R. Then (a · b) · c = 0.c = 0; a.(b · c) = a · 0 = 0 (By Def.)

∴ (a · b) · c = a · (b, c)∀a, b, c ∈ R ∴ (R, ·) is a semi group.

Let a, b, c ∈ R. a ∈ R, b + c ∈ R ⇒ a · (b + c) = 0

a ∈ R, b ∈ R ⇒ ab = 0; a ∈ R, c ∈ R ⇒ ac = 0 ⇒ ab + ac = 0 + 0 = 0.

Hence a · (b + c) = a · b + a · c

Similarly, we can prove that (b + c) · a = b · a + c· a.

∴ Distributive laws hold.

Example. 4. Prove that Z m = {0, 1, 2, . . . ., m− 1} is a ring with respect to addition and multiplication modulo m.

Solution. We denote addition modulo m by +m and multiplication modulo m by × m

We also know that a+m b = a + b(modm) = r where r is the remainder when a + b is divided by m. a × m b = ab(modm) = s where s is the remainder when ab is divided by m.

Let a, b, c ∈ Zm. a+m b = a + b( mod m) ∈ Zm ⇒ +m is a binary operation in Zm . a +m b = a + b(modm) = b + a(modm) = b +m a ⇒ +m is commutative in Zm

(a+m b) + mc = (a + b) + c(modm) = a + (b + c)(modm) = a +m (b +m c)

∴ +m is associative in Zm

There exists 0 ∈ Zm

such that 0 +m a = 0 + a(modm) = a(modm) = a.

⇒ 0 is the zero element.

For 0 ∈ Zm , we have 0 +m 0 = 0(modm) ⇒ additive inverse of 0 = 0.

For a 6= 0 ∈ Zm we have 0 < a < m ⇒ 0 < m − a < m ⇒ m − a ∈ Zm

a +m (m − a) = a + (m − a)(modm) = m(modm) = 0(modm)

∴ inverse of a 6= 0 ∈ Zm is m − a ∈ Zm

Hence ( Zm, +) is an abelian group.

Let a, b, c ∈ Zm. a× m b = ab(modm) ∈ Zm ⇒ × m is a binary operation in Zm

(a × m b) × m c = (ab)c(modm) = a(bc)(modm) = a × m (b × m c)

∴ × m is associative in Zm.

a× m (b+m c) = a(b+ c)( mod m) = ab+ ac( mod m) = (a × m b)+m (a × m c) and (b +m c) × m a = (b × m a) +m (c × m a) so that distributive laws hold.

∴ ( Zm ,+m, × m ) is a ring.

Note. Put m = 6 in the above proof to prove that Z6 is a ring.

Applications Of Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields In Mathematics

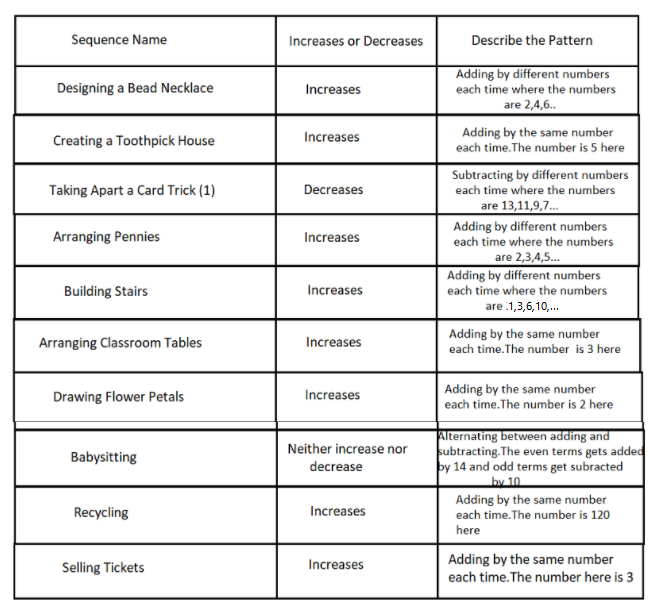

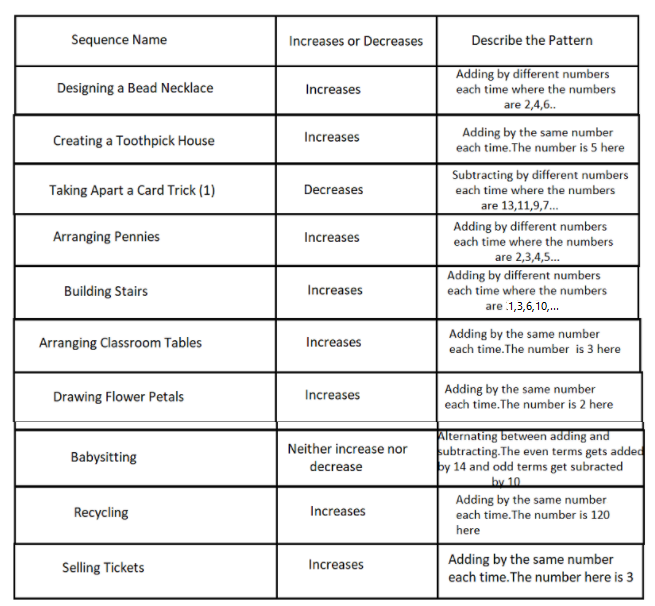

Example. 5. Prove that the set R = {a, b} with addition ( +) and multiplication (·) defined as follows is a ring

and

Solution. From the above tables, clearly +,· are binary operations in R.

1. (a + a) + b = a + b = b; a + (a + b) = a + b = b ⇒ (a + a) + b = a + (a + b) (a + b) + a = b + a = b; a + (b + a) = a + b = b ⇒ (a + b) + a = a + (b + a), etc,

∴ Associativity is true.

2. a ∈ R is the zero element because a + a = a, b + a = b

3. a + b = b = b + a ⇒ commutativity is true.

4. a + a = a ⇒ additive inverse of a = a and b + b = a ⇒ additive inverse of b = b.

5. a · (a · b) = a · a = a; (a · a) · b = a · b = a ⇒ a · (a · b) = (a · a) · b, etc

∴ Associativity is true.

6. a · (b + a) = a · b = a; a · b + a · a = a + a = a ⇒ a · (b + a) = a · b + a · a (b + a) · a = b · a = a; b · a + a · a = a + a = a ⇒ (b + a) · a = b · a + a · a, etc.

∴ Distributive laws are true.

Hence (R, +, ·) is a ring.

Example. 6. If R is a ring and a, b, c, d ∈ R then prove that

- (a + b)(c + d) = ac + ad + bc + bd, and

- a + b = c + d ⇔ a − c = d − b

Solution.

(1) (a + b)(c + d) = a(c + d) + b(c + d) = ac + ad + bc + bd ( By R6)

(2) a + b = c + d ⇔ (a + b) + (−b) = (c + d) + (−b)

⇔ a + (b + (−b)) = (c + d) + (−b)

⇔ a + 0 = (c + d) + (−b)

⇔ a + (−c) = (−c) + {(c + d) + (−b)}

⇔ a − c = ((−c) + c) + {d + (−b)}

⇔ a − c = 0 + (d − b) ⇔ a − c = d − b (By R4 )

Rings, Integral Domains And Fields Exercise 1

1( a )

1. If R is a ring and a, b, c ∈ R prove that (a − b) − c = (a-c) − b

2. If R is a ring and a, b ∈ R then prove that the equation a + x = b has unique solution in R.

3. In a ring R if ’ a ’ commutes with ’ b ’ prove that ’ a ’ commutes with ’ −b0 ’ where a, b ∈ R.

4. If R is a ring with unity element ’ 1 ’ and R6= {0} prove that 1 6= 0 where 0 ∈ R is the zero element.

5. R is a Boolean ring and for a ∈ R, 2a = 0 ⇒ a = 0 then prove that R = {0}. 6. If R is a commutative ring prove that (a + b)2 = a2 + 2ab + b2∀a, b ∈ R.

6. If R is a ring and a, b, c, d ∈ R evaluate (a − b)(c − d).

7. If R = {a√2 | a ∈ Q} is (R, +, ·) under ordinary addition and multiplication, a ring ?

8. Is the set of all pure imaginary numbers = {iy | y ∈ R} a ring with respect to addition and multiplication of complex numbers?

9. If Z = the set of all integers. and ’ n ’ is a fixed integer prove that the set nZ = {nx | x ∈ Z} is a ring under ordinary addition and multiplication of integers.

Answers

2. b − a 7. ac + bd − ad − bc 8. Not a ring 9. Not a ring

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Zero Divisors Of A Ring

Though rings are a generalisation of the number system some algebraic properties of the number system need not hold in general rings.

The product of two numbers can only be zero if at least one of them is zero, whereas in any ring it may not be true.

For example, in the ring (Z6, +, ·) of modulo −6, we have 2.3 = 0 with neither 2 = 0 nor 3 = 0.

Definition. (Zero Divisors). Two non-zero elements a, and b of a ring R are said to be zero divisors (divisors of zero) if ab = 0, where 0 ∈ R is the zero element.

In particular,’ a ’ is the left zero divisor, and ’ b ’ is the right zero divisor.

Definition. (Zero Divisor). a 6= 0 ∈ R is a zero divisor if there exists b 6= 0 ∈ R such that ab = 0.

Note. 1. In a commutative ring there is no distinction between left and right zero divisors.

2. A ring R has no zero divisors ⇔ a, b ∈ R and ab = 0 ⇒ a = 0 or b = 0

Example.1. The ring of integers Z has no zero divisors.

Step-By-Step Guide To Understanding Rings, Integral Domains, Fields

Example. 2. In the ring (Z12, +, ·), the elements 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10 are zero divisors.

For 2 · 6 = 0, 3 : 4 = 0, 3 · 8 = 0, 4 · 6 = 0, 4 · 9 = 0, 6 · 10 = 0

Observe that the G. C. D of any of {2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10} and 12 6= 1.

Example3. The ring (M2, +, ·) of 2 × 2 matrices whose elements are in Z, has zero divisors.

For, we have A = 10006= O, B = 00106= O, where O is a zero matrix, such that AB = O.

Example 4. The ring (Z3, +, ·) of modulo −3 has no zero divisors.

Example 5. The ring Z × Z = {(a, b) | a, b ∈ Z} has zero divisors.

For, (0, 1), (1, 0) ∈ Z × Z ⇒ (0, 1) · (1, 0) = (0, 0) = zero element in Z × Z.

Imp. In the ring of integers Z, all the solutions of x2 − 4x + 3 = 0 are obtained by factoring as x2 − 4x + 3 = (x − 1)(x − 3) and equating each factor to zero. While doing so, we are using the fact that Z is an Integral Domain, so that it has no zero divisors.

But if we want to find all solutions of an equation in a ring R which has zero divisors, we can do so, by trying every element in the Ring by substitution in the product (x − 1)(x − 3) for zero.

Example 6. In the ring Z of integers, the equation x2 +2x+4 = 0 i.e. (x+1) 2 +3 = 0 has no solution as (x + 1)2 + 3 ≥ 3∀x ∈ Z.

But, in the ring Z6 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}, (x+1)2 +3 takes respectively the values 4, 1, 0, 1, 4, 3 for x = 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 ∈ Z6.

∴ x2 + 2x + 4 = 0 has 2 ∈ Z6 as solution.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Cancellation Laws In A Ring

If (R, +, ·) is a ring, then (R, +) is an abelian group. So, cancellation laws with respect to addition are true in R. Now, we are concerned about the cancellation laws in R, namely ab = ac ⇒ b = c, ba = ca ⇒ b = c for a, b, c ∈ R with respect to multiplication.

Definition. (Cancellation laws). In a ring R, for a, b, c ∈ R if a6 = 0, ab = ac ⇒ b = c and a6 = 0, ba = ca ⇒ b = c then we say that cancellation laws hold in R.

Theorem. A ring R has no zero divisors if and only if the cancellation laws hold in R.

Proof. Let the ring have zero divisors. We prove that cancellation laws hold in R.

a, b, c ∈ R and a6 = 0, ab = ac ⇒ ab − ac = 0

⇒ a(b − c) = 0 ⇒ b − c = 0 ( ∵ a6 = 0) ⇒ b = c

Similarly we can prove a6 = 0, ba = ca ⇒ b = c

Conversely, let the cancellation laws hold in R. We prove that R has no zero divisors. If possible, suppose that there exist a, b ∈ R such that a6 = 0, b6 = 0, and ab = 0.

ab = 0 ⇒ ab = a0 ⇒ b = 0 (By cancellation law)

This is a contradiction.

∴ a6= 0, b6 = 0 and ab = 0 is not true in R.

∴ R has no zero divisors.

Note. The importance of having no zero divisors in a ring R, is, that an equation ax = b where a6 = 0, b ∈ R can have at most one solution in R.

For x1, x2 ∈ R if ax1 = b and ax2 = b then ax1 = ax2 ⇒ x1 = x2 (By cancellation law)

If a6 = 0 ∈ R has a multiplicative inverse, say, a− 1 ∈ R then the solution is a− 1b ∈ R.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Solved Problems

Example. 1. Find the zero-divisors of Z12, the ring of residue classes modulo – 12.

Solution. Z12 = {0, 1, . . . . . . .11}.

For a¯ 6= 0 ∈ Z12 there should exist ¯b ∈ Z12 such that a¯ × ¯b ≡ 0(mod12)

We have 2 × 6 = 0, 3 × 4 = 0, 4 × 3 = 0, 6 × 2 = 0, 8 × 3 = 0, 8 × 6 = 0, 8 × 9 = 0, 10 × 6 = 0

∴ 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10 are zero divisors.

Worked Examples Of Integral Domains In Abstract Algebra

Example. 2. Solve the equation x2 − 5x + 6 = 0 in the ring Z12.

Solution.

Given

x2 − 5x + 6 = 0

In the ring of integers Z, which has no zero divisors, x2 − 5x + 6 = 0 ≡ (x − 2)(x − 3) = 0 has two solutions 2, 3 ∈ Z.

But in Z12; for x = 6, (x − 2)(x − 3) = (4)(3) = 12 = 0 and for x = 11, (x − 2)(x − 3) = (9)(8) = 72 = 0.

∴ the given equation has 4 solutions, namely, 2,3,6, and 11 in the ring Z12.

Example. 3. In the ring Zn, show that the zero divisors are precisely those elements that are not relatively prime to n. (or) show that every non-zero element of Zn is a unit or zero divisor:

Solution. Let m ∈ Zn = {0, 1, 2, . . . , n − 1} and m 6= 0. Let m be not relatively prime to n.

Then G. C.D of m, n = (m, n) 6= 1.

Let (m, n) = d.

We have (m, n) = d ⇒ md , nd = 1 ⇒ md , nd ∈ Zn and md 6= 0, nd 6= 0

∴ m nd = md n = 0(modn). Thus m 6= 0, nd 6= 0 ⇒ m nd = 0

⇒ m is a zero divisor.

∴ Every m ∈ Zn which is not relatively prime to n is a zero divisor.

Let m ∈ Zn be relatively prime to n.

Then (m, n) = 1

∴ Let mr = 0 for some r ∈ Zn.

We have mr = 0(modn) ⇒ n| mr ⇒ n| r ( ∵ (m, n) = 1) ⇒ r = 0 (0 ≤ r < n − 1)

∴ If m ∈ Zn is relatively prime to n then m is not a zero divisor.

Note. If p is a prime, then Zp ring has no zero divisors.

Theorems And Properties Of Rings And Fields With Examples

1. (g) Some Special Types Of Rings

Definition. (Integral Domain)

A commutative ring with unity containing no zero divisors is an Integral Domain.

Note. 1. Some authors define integral domain without a unity element.

2. For “Integral Domain” we simply use the word “Domain” and denote by the symbol D. Imp. D is an integral domain ⇔

- D is a ring,

- D is commutative,

- D has a unity element and

- D has no zero divisors.

Example 1. The ring of integers Z is naturally an integral domain.

1 ∈ Z is the unity element and ∀a, b ∈ Z we have ab = ba (commutativity) and ab = 0 ⇒ a = 0 or b = 0 (no zero divisors).

Example 2. (Z6, +, ·) where Z6 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}, the set of integers under the modulo −6 system, is a ring. 1 ∈ Z6 is the unity element and ∀a, b ∈ Z6 we have ab(mod6) = ba(mod6)( commutative ) But, for 2 6= 0, 3 6= 0(mod6), 2.3 = 6(mod6) = 0 and hence Z6 has zero divisors. Therefore, Z6 is not an integral domain.

Example. 3. If Q = the set of all rational numbers and R = the set of all real numbers then (Q, +, ·) and (R, +, ·) are integral domains.

Example 4. -7 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}, the set of all integers under modulo −7 is an integral domain with respect to addition and multiplication modulo −7.

Example 5. The ring (M2, +, ·) of 2× 2 matrices is not an integral domain because it is not commutative and has zero divisors.

Example 6. Z × Z = {(a, b) | a, b ∈ Z} is not an Integral Domain under the addition and multiplication of components.

Theorem. 1. In an integral domain, cancellation laws hold.(Write the proof of (1) part of a theorem in Art. 1.6)

Theorem. 2. A commutative ring with unity is an integral domain if and only if the cancellation laws hold. (Write the proof of a theorem in Art. 1.6)

Definition. (Multiplicative Inverse). Let R be a ring with the unity element ’

1 ’. A non-zero element a ∈ R˙ is said to be invertible under multiplication, if there exists b ∈ R such that ab = ba = 1, b ∈ R is called the multiplicative inverse of a ∈ R.

From the theory of groups, the multiplicative inverse of a 6= 0 ∈ R, if exists, is unique. It is denoted by a − 1. Also aa− 1 = a− 1a = 1.

Definition. (Unit of a Ring). Let R be a ring with unity. An element u ∈ R is said to be a unit of R if it has a multiplicative inverse in R.

Note.

1. The zero element of a ring is not a unit.

2. The unity element of a ring and the unit of a ring R is different. The unity element is the multiplicative identity while a unit of a ring is an element of the ring having a multiplicative inverse in the ring. Of course, the unity element is a unit.

Integral Domains And Fields Classification With Solved Examples

Theorem. 3. In a ring R with unity, if a (6= 0) ∈ R has a multiplicative inverse, then it is unique.

Proof. Suppose that there exist b, b0 ∈ R such that ab = ba = 1 and ab0 = b0a = 1.

Then ab = ab0 = 1.

By the definition of cancellation law, b = b0.

Example 1. It is a ring with a unity element = 1. We have 1.1 = 1 and (−1)(−1) = 1 for −1, 1 ∈ Z.

If a 6= ±1 ∈ Z then there exists no b ∈ Z such that ab = ba = 1.

Therefore, −1;1 are the only units in the ring Z.

Observe that any element is also a unit.

Example 2. Consider the ring Z7 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} under addition and multiplication modulo −7.

It has a unity element = 1 which is also a unit.

Further 24 = 4.2 = 1(mod7), 3.5 = 5.3 = 1(mod7) and 6.6 = 1(mod7). Thus every non-zero element is a unit.

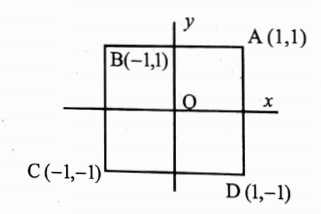

Example 3. Consider the ring Z × Z = {(m, n); m, n ∈ Z}.

The unity element = (1, 1) which is also a unit: Also, (1, −1)(1, −1) = (1.1, (−1)(−1)) = (1, 1); (−1, 1)(−1, 1) = (1, 1) and (−1, −1)(−1, −1) = (1, 1)

Thus (1, 1), (1, −1), (−1, 1) and (−1, −1) are units in Z × Z.

Definition. (Division Ring or Skew Field) Let R be a ring with a unity element.

If every non-zero element of R is a unit then R is a Division Ring. (R, +,)isaDivisionring ⇔ (1)R is a ring, (2) R has a unity element and (3) every non-zero element in R is invertible under multiplication.

Example 1. ( Z, +,) is not a division ring, for, 2 6= 0 ∈ Z has no multiplicative inverse in Z.

Example 2. (Q, +, ·) and (R, +, ·) are division rings.

Example 3. The ring (M2, +, ·) of non-singular 2 × 2 matrices is a division ring.

Definition. (Field) Let R be a commutative ring with a unity element. If every nonzero element of R is invertible under multiplication then R is a field.

Another Definition. A commutative ring with unity is called a field if every nonzero element is a unit.

(R, +, ·) is a field ⇔ (1)R is a ring, (2) R is commutative (3) R has a unity element and (4) every non-zero element of R is a unit. Usually, a field is denoted by the symbol F.

Note. 1 . A division ring which is also commutative is a field.

2. In a field, the zero element and the unity element are different. Therefore, a field has at least two elements.

Example 1. We know that (Q, +) where Q = the set of all rational numbers is an additive group and (Q − {0}, ·) is a multiplicative group. Further distributive laws hold. Therefore (Q, +, ·) is a field.

Example 2. (Z, +, ·) where Z = the set of all integers is not a field, because all non-zero elements of Z are not units.

Example 3. (Z7, +, ·) where Z7 = the set of integers under modulo −7 is a field.

Theorem. 4. A field has no zero – divisors.

Proof. Let (F, +, ·) be a field.

Let a, b ∈ F and a6= 0.

a6= 0 ∈ F, F is a field ⇒ there exists a−1 ∈ F such that aa−1 = a−1a = 1.

ab = 0. ⇒ a−1(ab) = a−10 ⇒ a−1a b = 0 ⇒ 1b = 0 ⇒ b = 0

Thus a, b ∈ R, a6 = 0 and ab = 0 ⇒ b = 0.

Similarly, we can prove that, a, b ∈ R, b6 = 0 and ab = 0 ⇒ a = 0.

∴ F has no zero divisors.

Note. A division ring has no zero divisors. (Write the proof of the theorem (3))

Theorem. 5. Every field is an integral domain.

Proof. Let (F, +, ·) be a field. Then the ring F is a commutative ring with unity and having every non-zero element as a unit.

But an integral domain is a commutative ring with unity and having no zero divisors. So, we have to prove that F has no zero divisors. (Write the proof of the above Theorem (3))

Note. The converse of the above theorem need not be true. However, an integral domain with a finite number of elements can become a field.

Theorem 6. Every finite integral domain is a field.

Proof. Let 0, 1, a1, a2, . . . . . . , an be all the elements of the integral domain D.

Then D has n + 2 elements which is finite. Integral domain D is a commutative ring with unity and having no zero divisors.

So, we have to prove that every non-zero element of D has a multiplicative inverse in D.

Let a ∈ D and a6 = 0

Now consider the n + 1 products a1, aa1, aa2 , . . . ., aan.

If possible, suppose that aai = aaj for i 6= j.

Since a6 = 0, by cancellation law, we have ai = aj.

This is a contradiction since i 6= j.

Therefore a1, aa1, aa2, . . . . . . . . . , aan are (n + 1) distinct elements in D.

Since D has no zero divisors, none of these (n +1) elements is zero element.

Hence, by counting ;

a1, aa1, aa2, . . . . . . .., aan are the (n+1) elements 1, a1, a2, . . . . . . , an in some order.

∴ a1 = 1 or a = 1 or aai = 1 for some i.

For a6 = 0 ∈ D there exists b = ai ∈ D such that ab. = 1

⇒ a6 = 0 ∈ D has a multiplicative inverse in D.

∴ D is a field.

Theorem 7. If p is a prime then Zp, the ring of integers modulo p, is a field.

Proof. In Example 4 on page 191, we proved that (Zp, +, ·) is a ring.

Since Z

p = {0, 1, 2, . . . . . . , p − 1} has p distinct elements, and Zp is a finite ring.

We prove now that Zp is an integral domain.

Clearly, 1 ∈ Zp is the unity element.

For a, b ∈ Zp, ab(modp) ≡ ba(modp) ⇒ ab = ba and hence Zp is commutative.

For a, b ∈ Zp and ab = 0 ⇒ ab ≡ 0(modp) ⇒ p|ab ⇒ p|a or p | b ( ∵ p is prime)

⇒ a ≡ 0(modp) or b ≡ 0(modp) ⇒ a = 0 or b = 0.

∴ Zp has no zero divisors. Thus (Zp, +, ·) is a finite integral domain .

∴ Zp is a field.

Theorem. 8. If (Zn, +, ·) is a field then n is a prime number.

Proof. If possible let m be a divisor of n.

∴ there exists q ∈ Z such that n = mq. Clearly 1 ≤ m, q ≤ n.

mq = n ⇒ mq ≡ 0(modn). Since Zn is a field, Zn has no zero divisors.

∴ mq ≡ 0(modn) ⇒ m = 0(modn) or q = 0(modn)

⇒ m = n or q = n ⇒ m = n or m = 1( ∵ mq = n). ∴ n is a prime number.

Theorem. 9. Z p = {0, 1, 2, . . . , p − 1} is a field if and only if p is a prime number.

Proof. Write the proofs of Theorem 7 and Theorem 8.

Note. In the field Zp= {0, 1, 2, . . . . . . , p − 1} where p is a prime, 1 and p − 1

are the only elements that are their own multiplicative inverses.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Solved Problems

Example. 4. Find all solutions of x2 − x + 2 = 0 over Z3[1].

Solutions.

Given

x2 − x + 2 = 0

We have Z3 = {0, 1, 2} under modulo – 3 system. Z3[1] = {a + ib | a, b ∈ Z3 and i2 = −1 = {0, 1, 2, i, 1 + i, 2 + i, 2i, 1 + 2i, 2 + 2i}, containing 9 elements.

Let P(x) = x2 − x+2. Then P(0) 6= 0, P(1) 6= 0, P(2) 6= 0, P(i) = −1− i+2 6= 0

P(1 + i) = (1 − 1 + 2i) − 1 − i + 2 6= 0, P(2 + i) = (4 − 1 + 4i) − (2 + i) + 2 6= 0, P(2i) = −4 6= 0

P(1+2i) = (1−4+4i)−(1+2i)+2 6= 0, P(2+2i) = (4−4+8i)−(2+2i)+2 6= 0

∴ x2 − x + 2 = 0 has no solution over Z3[1].

Example. 5. Show that 1, p − 1 are the only elements of the field Zp, p is prime, that are their own multiplicative inverses.

Solution. Observe that, in the Zp field, x2 − 1 = 0 has only two solutions.

x2 − 1 = 0 ⇒ x2 = 1 ⇒ x = 1 ⇒ Multiplicate inverse of x = x.

So, we have to prove that 1, p − 1 are solutions of x2 − 1 = 0 in Zp.

1 ∈ Z

p ⇒ 12 − 1 = 1 − 1 = 0

p − 1 ∈ Zp ⇒ (p − 1) 2 − 1 = p2 − 2p + 1 − 1 = p2 − 2p

= p(p − 2) = 0(p − 2) = 0 ( ∵ p = 0(modp))

Example. 6. In a ring R with unity if a ∈ R has multiplicative inverse then a ∈ R is not a zero divisor.

Solution. a ∈ R has multiplicative inverse

⇒ There exists a−1 ∈ R, such that aa−1 = a−1a = 1, where 1 ∈ R is the unity element, To prove that a ∈ R is not a zero divisor we have to prove that

for b ∈ R so that ab = 0 or ba = 0 ⇒ b = 0 only.

ab = 0 ⇒ a−1(ab) = a−10 ⇒ 1b = 0 ⇒ b = 0; ba = 0 ⇒ (ba)a−1 = 0a−1 ⇒ b1 = 0 ⇒ b = 0

∴ a ∈ R is not a zero divisor.

Example. 7. Construct a field of two elements.

Solution. Let F = {0, 1} and addition ( +), multiplication ( ) in F be defined as follows :

Clearly, + and – are binary operations in F.

We have 0 + 1 = 1 + 0 and 0.1 = 1.0 and hence +, · are commutative.

The two operations are associative.

0 ∈ F is the zero elements and 1 ∈ F is the unity element.

Clearly, distributivity is also true.

Additive inverse of 0 = 0, additive inverse of 1 = 1.

The multiplicative inverse of 16= 0 ∈ F is 1 .

Hence ({0, 1}, +, ·) is a field.

Example. 8. Show that the set R of all real-valued continuous functions defined on [0, 1] is a commutative ring with unity, with respect to addition (+) and multiplication ( •) of functions defined as (f + g)(x) = f(x) + g(x) and (f · g)(x) = f(x) · g(x)∀x ∈ [0, 1] and f, g ∈ R.

Solution. f, g are real-valued continuous functions on [0, 1] ⇒ (1)f + g and f.g are real-valued continuous functions on [0, 1] and (2) f(x), g(x) are real numbers for x ∈ [0, 1].

∴ The addition and multiplication of functions are binary operations in R.

Let f, g, h ∈ R ∀x ∈ [0, 1], ((f + g) + h)(x) = (f + g)(x) + h(x) = (f(x) + g(x)) + h(x)

= f(x) + (g(x) + h(x)) = f(x) + (g + h)(x) = (f + (g + h))(x)

∴ (f + g) + h = f + (g + h)∀f, g, h ∈ R

If O(x) = 0∀x ∈ [0, 1] then O is a real-valued continuous function.

Therefore there exists O ∈ R so that (f + O)(x) = f(x) + O(x) = f(x)∀x ∈ [0, 1] and f ∈ R.

If f is a real-valued continuous function on [0, 1] then ’ −f0 ’ is also a real-valued continuous function so that (−f)(x) = −f(x)∀x ∈ [0, 1].

Therefore for f ∈ R there exists −f ∈ R so that (f + (−f))(x) = f(x) − f(x) = 0 = 0(x)∀x ∈ [0, 1]

That is, additive inverse exists ∀f ∈ R. ∴ (R, +) is a commutative group.

∀x ∈ [0, 1]; ((fg)h)(x) = (fg)(x)h(x) = (f(x)g(x))h(x) = f(x)(g(x)h(x)) = f(x)(gh)(x) = (f(gh))(x)

∴ (fg)h˙ = f(gh)∀f, g, h ∈ R

∀x ∈ [0, 1]; (f(g + h))(x) = f(x)(g + h)(x) = f(x)(g(x) + h(x)) = f(x)g(x) + f(x)h(x) = (fg)(x) + (fh)(x) = (fg + fh)(x)

∴ f(g + h) = fg + fh∀f, g, h ∈ R

Similarly (g + h)f = gf + hf ∀f, g, h ∈ R. Hence (R, +, ·) is a ring.

∀x ∈ [0, 1], (fg)(x) = f(x)g(x) = g(x)f(x) = (gf)(x)

∴ fg = gf∀f, g ∈ R.

∴ R is a commutative ring.

The constant function e(x) = 1∀x ∈ [0, 1] is real-valued and continuous.

Also e ∈ R is such that (ef)(x) = e(x)f(x) = f(x)∀x ∈ [0, 1]

∴ e ∈ R defined as above is the unity element.

Example 9. Prove that the set Z[1] = a + bi | a, b ∈ Z, i 2 = −1 of Gaussian integers is an integral domain with respect to the addition and multiplication of numbers. Is it a field?

Solution. Let Z(1) = {a + bi | a,b ∈ Z}.

Let x, y ∈ Z (i) so that x = a + bi,y = c + di where a,b,c,d ∈ Z

x + y = (a + c) + (b + d)i = a1 + b1 i where a1 = a + c, b1 = b + d ∈ Z

x,y = (ac − bd) + (ad + bc)i = a2 + b2 i where a2 = ac − bd,b2 = ad + bc ∈ Z

∴ +, · are binary operations in Z(1).

Since the elements of Z (1) are complex numbers we have that

- Addition and multiplication are commutative in Z(1),

- Addition and multiplication are associative in Z (1) and

- Multiplication is distributive over addition in Z(1).

Clearly zero element = 0 + 0i = 0 and unity element = 1 + 0i = 1.

Further, for every x = a + ib ∈ Z(i) we have −x = (−a) + i(−b) ∈ Z(i) so that x + (−x) = {a + (−a)} + i{b + (−b)} = 0 + i0 = 0 ⇒ Additive inverse exists.

∴ Z(i) is a commutative ring with a unity element.

For x,y ∈ Z(i),x.y = 0 ⇒ x = 0 or y = 0 since x,y are complex numbers.

Hence Z(i) is an integral domain with a unity element.

For α = 3 + 4i 6= 0 ∈ Z(i) we have β = 253 − i 254 so that α · β˙ = 259 + 1625 + i −2512 + 1225 = 1 + i0 = 1. But β /∈ Z(i) as 253 , − 254 ∈/ Z.

So, every non-zero element of Z(i) is not invertible. ∴ Z(i) is not a field.

Example. 10. Prove that Q[√2] = {a + b√2 | a,b ∈ Q} is a field with respect to ordinary addition and multiplication of numbers.

Solution. Let x,y,z ∈ Q[√2] so that

x = (a1 + b1)√2,y = (a2 + b2)√2,z = (a3 + b3)√2 where a1,b1,a2,b2,a3,b3 ∈ Q

x+y = (a1 + a2)+(b1 + b2) √2 = a+b√2 where a1 +a2 = a,b1 +b2 = b ∈ Q

x · y = (a1a2 + 2b1b2)+(a1b2 + a2b1) √2 = c+d√2 where c = a1a2 +2b1b2 ∈ Q and d = a1b2 + a2b1 ∈ Q

∴ Addition (+) and multiplication ( ) of numbers are binary operations in Q[√2].

x + y = (a1 + a2) + (b1 + b2) √2 = (a2 + a1) + (b2 + b1) √2 = (a2 + b2)√2+ (a1 + b1)√2 = y + x ⇒ Addition is commutative.

(x + y) + z = (a1 + a2 + a3) + (b1 + b2 + b3) √2 and x + (y + z) = (a1 + a2 + a3) + (b1 + b2 + b3) √2 ⇒ (x + y) + z = x + (y + z) ⇒ Addition is associative.

For 0 ∈ Q we have 0 + 0√2 = 0 ∈ Q[√2] so that x + 0 = x for x ∈ Q[√2] ⇒ 0 ∈ Q[√2] is the zero element.

For x = (a1 + b1)√2 ∈ Q[√2] we have −x = (−a1) + (−b1) √2 ∈ Q[√2] so that x + (−x) = 0 ⇒ Additive inverse exists.

∴ (Q[√2], +) is a commutative group.

x · y = (a1 + b1)√2 · (a2 + b2)√2 = (a1a2 + 2b1b2) + (a1b2 + a2b1) √2 = (a2a1 + 2b2b1)+(a2b1 + b2a1) √2 = y·x ⇒ Multiplication is commutative.

(x · y) · z = (a1a2 + 2b1b2 + a1b2 + a2b1)√2 · (a3 + b3)√2 = (a1a2a3 + 2b1b2 a3 + 2a1b2b3 + 2a3b1b3)+(a1a2b3 + 2b1b2b3 + a1a3b2 + a2a3b1) √2 and x · (y · z)

= (a1 + b1)√2 (a2a3 + 2b2b3 + a2b3 + a3b2)√2 = (a1a2a3 + 2a1b2b3 + 2a2b1b3 + 2a 3b1b2)+(a1a2b3 + a1a3b2 + a2a3b1 + 2b1b2b3) √2

∴ (x, y), z = x.(y, z) ⇒ Multiplication is associative.

x · (y + z) = (a1 + b2)√2 (a2 + a3 + b2 + b3)√2 = (a1a2 + a1a3 + 2b1b2 + 2b1b3) + (a1b2 + a1b3 + a2b1 + a3b1) √2 and x·y+x, z = (a1a2 + 2b1b2 + a1b2 + a2b1)√2 +(a1a3 + 2b1b3 + a1b3 + a3b1)√2 = (a1a2 + 2b1b2 + a1a3 + 2b1b3) + (a1b2 + a2b1 + a1b 3 + a3b1) √2

∴ x · (y + z) = x · y + x · z ⇒ Distributivity is true.

Hence (Q[√2], +, ·) is a ring.

1 = 1 + 0√2 ∈ Q[√2] so that x1 = (a1 + b1)√2 (1 + 0√2) = x∀x ∈ Q[√2].

∴ Q[√2] is a commutative ring with a unity element.

To show that Q[√2] is a field we have to prove further every non-zero element in Q[√2] has a multiplicative inverse.

Let a + b√2 ∈ Q[√2] and a 6= 0 or b 6= 0

⇒ Then \(\frac{1}{a+b \sqrt{2}}=\frac{a-b \sqrt{2}}{a^2-2 b^2}=\left(\frac{a}{a^2-2 b^2}\right)+\left(\frac{-b}{a^2-2 b^2}\right) \sqrt{2}\)

⇒ since \(a^2-2 b^2 \neq 0 for a \neq 0 or b \neq 0. a, b \in Q \Rightarrow \frac{a}{a^2-2 b^2}, \frac{-b}{a^2-2 b^2} \in Q\)

⇒ For \(a+b \sqrt{2} \neq 0 \in Q[\sqrt{2}]\)

there exists \(\left(\frac{a}{a^2-2 b^2}\right)+\left(\frac{-b}{a^2-2 b^2}\right) \sqrt{2} \in Q[\sqrt{2}]\)

⇒ such \(t(a+b \sqrt{2})\left[\left(\frac{a}{a^2-2 b^2}\right)+\left(\frac{-b}{a^2-2 b^2}\right) \sqrt{2}\right]=1=1+0 \sqrt{2}\)

∴ Every non-zero element of Q[√2] is invertible.

Hence Q[√2] is a field. Ex.

Example11. If Z = the set of integers then prove that the set z × z = {(m, n) | m, n ∈ z} with respect to addition (+) and multiplication (•) defined as (m1, n1) + (m2, n2) = (m1 + m2, n1 + n2) and (m1, n1) · (m2, n2) = (m1m2, n1n2) ∀ (m1, n1) , (m2, n2) ∈ z × z is a ring and not an integral domain.

Solution.

Let x = (m1, n1) , y = (m2, n2) , z = (m3, n3) ∈ z×z so that m1, n1, m2, n2, m3, n3 ∈ Z

(1) x + y = (m1, n1) + (m2 + n2) = (m1 + m2, n1 + n2) ∈ z × z x · y = (m1, n1) · (m2, n2) = (m1m2, n1n2) ∈ z × z as m1 + m2, n1 + n2, m1m2, n1n2 ∈ z

∴ + and · are binary operations in z × z

(2) x + y = (m1 + m2, n1 + n2) = (m2 + m1, n2 + n1) = y + x and x.y = (m1m2, n1n2) = (m2m1, n2n1) = yx ⇒ + and · are commutative.

(3) (x + y) + z = (m1 + m2, n1 + n2) + (m3, n3) = (m1 + m2 + m3, n1 + n2 + n3) = (m1 + m2 + m3, n1 + n2 + n3) = x + (y + z) (x · y) · z = (m1m2, n1n2) · (m3, n3) = ((m1m2) m3, (n1, n2) n3) = (m1 (m2m2) , n1 (n2n3)) = x.(y.z). ⇒ + and – are associative.

(4) x · (y + z) = (m1, n1) · (m2 + m3, n2 + n3) = (m1 (m2 + m3) , n1 (n2 + n3)) = (m1m2 + m1m3, n1n2 + n1n3) = (m1m2, n1n2) + (m1m3, n1n3) = x · y + x · z

Since multiplication is commutative, (y + z) · x = y · x + z · x

∴ Distributivity is true.

(5) For 0 ∈ z we have (0, 0) ∈ z×z and (m, n)+(0, 0) = (m+0, n+0) = (m, n)

∴ (0, 0) ∈ z × z is the zero elements.

(6) For 1 ∈ z we have (1, 1) ∈ z × z and (m, n).(1, 1) = (m · 1, n · 1) = (m, n)

∴ (1, 1) ∈ z × z is the unity element. Hence z × z is a commutative ring with unity.

But we have, (0, 1), (1, 0) ∈ z × z and (0, 1) 6= (0, 0), (1, 0) 6= (0, 0) such that (0, 1) · (1, 0) = (0 · 1, 1 · 0) = (0, 0)

∴ (0, 1), (1, 0) are zero divisors in z× z. Hence z× z is not an integral domain.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Exercise 2

1. List all zero divisors in the ring Z20. Also, find the units in Z20. Is there any relationship between zero divisors and units?

2. Solve the equation 3x = 2 in (a) Z7 (b)Z23

3.

- Find all solutions of x3 − 2x2 − 3x = 0 in Z12.

- Find all solutions of x2 + x − 6 = 0 in Z14 .

4. Describe all units in (a) Z4 (b) Z5. Prove that Z2 × Z2 = {(0, 0), (0, 1), (1, 0), (1, 1)} under componentwise addition and multiplication is a Boolean ring.

5. Find all solutions of a2 + b2 = 0 inZ7.

6. Write the multiplication table for Z3[1] = {0, 1, 2,i, 1+i, 2+i, 2i, 1+2i, 2+ 2i}.

7. R is a set of real numbers. Show that R × R forms a field under addition and multiplication defined by (a,b) + (c,d) = (a + c,b + d) and (a,b) : (c,d) = (ac − bd,ad + bc) is a field. (Hint. R × R = C = a + ib | a,b ∈ R,i2 = −1 )

9. If Z is the set of all integers and addition ⊕, multiplication (x) is defined in Z as a ⊕ b = a + b − 1 and a × b = a + b − ab∀a,b ∈ Z then prove that (Z, ⊕, ×) is a commutative ring.

10. Let (R, +) be an abelian group. If multiplication (·) in R is defined as a · b = 0, 0000 is the zero element in R, ∀a,b ∈ R then prove that (R, +, ·) is a ring.

11. If R = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4} prove that (R, +5, x5) under addition and multiplication modulo – 5 is a field.

12. Give examples of (1) a commutative ring with unity (2) an integral domain and (3) a Division ring.

13. If R = the set of all even integers and (+) is ordinary addition and multiplication (∗) is defined as a ∗ b = ab2 ∀a,b ∈ R then prove that (R, +, ∗) is

a commutative ring.

14. S is a non-empty set containing n elements. Prove that P(S) forms finite Boolean ring w.r.t ’+’ and ’ ’ ’defined as A + B = (A ∩ B) − (A ∪ B) and

A · B = A ∩ B∀A, B ∈ P(S). Find addition and multiplication tables when S = {a,b}.

15. If R1, R2,……, Rn are rings, then prove that R1 × R2 × ……. Rn = {(r1,r2,……, rn) | ri ∈ Ri} forms a ring under componentwise addition and multiplication, that is, (a1,a2,……, an)+(b1,b2,……, bn) = (a1 + b1,a2 + b2,…, an + bn) and (a1,a2,……, an) · (b1,b2,……, bn) = (a1b1,a2b2,…., an bn)

Rings, Integral Domains & Fields Integral Multiples And Integral Powers Of An Element

Integral multiples: Let (R, +, ·) be a ring and a ∈ R. We define 0a = O where ’ 0 ’ is the integer and O is the zero element of the ring

If n ∈ N we define na = a + a + . . . + a, (n terms ).

If n is negative integer, na = (−a) + (−a) + . . . + (−a), (−n terms ).

(−n)a = (−a) + (−a) + . . . + (−a), n terms = n(−a) = −(na) where n ∈ N.

The set {na | n ∈ Z, a ∈ R} is called the set of integral multiples of an element ’ a ’. It may be noted that for n ∈ Z, a ∈ R we have na ∈ R. Theorem.

If m, n ∈ Z and a, b ∈ R, a ring, then (1)(m + n)a = ma + an, (2) m(na) = (mn)a, (3) m(a + b) = ma + mb and (iv)m(ab) = (ma)b. (Proof is left as an exercise )

Note 1. If the ring R has unity element then for n ∈ Z and a ∈ R we have na = (n1)a = (n1)a

2. If m, n ∈ Z and a, b ∈ R, a ring then we have (ma)(nb) = m{a(nb)} = m{(na)b} = m{n(ab)} = (mn)(ab).

Integral powers: Let (R, +, ) be a ring and a ∈ R.

For n ∈ N we write an = a.a . . . a(n times ).

It may be noted that an = an − 1.a.

Theorem. If m, n ∈ N and a, b ∈ R, a ring then

am · an = am +n and

(am)n = amn (Proof is left as an exercise )

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Idempotent Element And Nilpotent Element Of A Ring

Definition. In a ring R, if a 2 = a for a ∈ R then ’ a ’ is called an idempotent element of R with respect to multiplication.

Theorem. 1. If a 6= 0 is an idempotent element of an integral domain with unity then a = 1.

Proof. Let (R, +, ·) be an integral domain.

a6 = 0 ∈ R is an idempotent element ⇒ a 2 = a

∵ a2 = a1 ( ∵ al = a)

⇒ a2 − a1 = 0 ⇒ a(a − 1) = 0 (’ 0 ’ is the zero element)

⇒ a − 1 = 0 since R has no zero divisors ⇒ a = 1.

Note. 1. An integral domain with unity contains only two idempotent elements ’ 0 ’ and ’1’.

2. A division ring contains exactly two idempotent elements.

3. The product of two idempotent elements in a commutative ring R is idempotent.

For, (ab)2 = (ab)(ab) = a(ba)b = a(ab)b = (aa)(bb) = a2b2 = ab for a, b ∈ R which are idempotent:

Definition. Let R be a ring and a 6= 0 ∈ R. If there exists n ∈ N such that an = 0 then ’ a ’ is called a nilpotent element of R.

Theorem. 2. An integral domain has no nilpotent element other than zero.

Proof. Let R be an integral domain and a6 = 0 ∈ R.

we have a 1 = a6 = 0, a2 = a · a6 = 0 since R has no zero divisors.

Let an ≠ 0 for n ∈ N.

Then an +1 = an. a6 = 0, since R has no zero divisors.

∴ By induction, a6 = 0 for every n ∈ N.

Hence a6 = 0 ∈ R is not a nilpotent element.

Example1. In the ring (Z6, +, ·), 3 and 4 and idempotent elements, for 32 = 3 and 42 = 4.

Example 2. In the ring (Z8, +, ·), there are no idempotent elements.

Example 3. In the ring (Z8, +, ·), 2 and 4 are nilpotent elements, for 23 = 0 and 42 = 0.

Example 4. In the ring Z6, +˙, there are no nilpotent elements.

Example. 1. If a,b are nilpotent elements in a commutative ring R then prove that a + b, a · b are also nilpotent elements.

Solution.

Given

a,b are nilpotent elements in a commutative ring R

a,b ∈ R are nilpotent elements

⇒ there exists m,n ∈ N such that am = 0,bn = 0. We have

⇒ (a + b)m+n = am+n + (m + n)C1 · am+n−1 · b + … + (m + n)Cn · am · bn + … + … + bm+n = am an + (m + n)C1an−1 · b + (m + n)C2 · an−2 · b2 + … + (m + n)Cn · bn + (m + n)Cn+1 · am−1 · b + (m + n)Cn+2 · am−2 · b2 + … + bm bn = 0 ( ∵ am = 0 = bn.)

Also, (ab)mn = amn · bmn = (am)n (bn)m = 0 ( ∵ R is commutative ).

∴ a + b and a · b are nilpotent elements.

Rings, Integral Domains And Fields Characteristic Of A Ring

Definition. The characteristic of a ring R is defined as the least positive integer p such that pa = 0 for all a ∈ R. In case such a positive integer p does not exist then we say that the characteristic of R is zero or infinite.

Note.

1. If R is a ring and Z = {n ∈ N | na = 0∀a ∈ R} 6= φ then the least element in Z is the characteristic of R.

2. If the ring R has characteristic zero then ma = 0 ’ where a 6= 0 can hold only if m = 0.

3. If the characteristic of a ring R is not zero then we say that the characteristic of R is finite.

4. As the integral domain, division ring and field are also ring characteristics that have meaning for these structures. Imp. If for some a ∈ R, pa 6= 0 then characteristic of R 6= p. Characteristic of a ring R = p ⇒ pa = 0∀a ∈ R.

Example 1 . R = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6} = Z7 is a ring under addition and multiplication modulo 7. Zero element of R = 0.

∀a ∈ R we have 7a ≡ 0(mod7) ⇒ 7a = 0∀a ∈ R. Further for 1 ∈ R, p(1) = p 6= 0 where p 6= 0 and 0 < p < 7.

∴ 7 is the least positive integer so that 7a = 0∀a ∈ R ⇒ Characteristic of R = 7.

Example. 2. The characteristic of the ring (Z, +, ·) is zero. For, there is no positive integer n so na = 0 for all a ∈ Z.

Example3. If R 6= {0} and the characteristic of R is not zero then the characteristic of R > 1.

Characteristic of R = 1 ⇒ 1a = 0∀a ∈ R ⇒ a = 0∀a ∈ R ⇒ R = {0}.

Example 4. For any element x ∈ Z3[1] ring, we have 3x = 0∀x ∈ Z3[1] ⇒ characteristic of Z3[i] = 3.

Example. 5. In the ring, R = {0, 3, 6, 9} ⊂ Z12, 4x = 0∀x ∈ R, and ’ 4 ’ is the least positive integer.

∴ Characteristic of R = {0, 3, 6, 9} = 0

Theorem 1. If R is a ring with a unity element, then R has characteristic p > 0 if and only if p is the least positive integer such that p1 = 0.

Proof.

Let characteristic of R = p(> 0)

By definition, pa = 0∀a ∈ R. In particular p1 = 0.

Conversely, let p be the least positive integer such that p1 = 0.

∴ q < p and q ∈ N ⇒ q1 6= 0. Then for any a ∈ R we have

p · a = a + a + . . . + a(p terms ) = a(1 + 1 + . . . + 1) = a(p1) = a0 = 0.

∴ p is the least positive integer so that p.a = 0∀a ∈ R. ∴ Characteristic of R = p.

Theorem 2. The characteristic of a ring with a unity element is the order of the unity element regarded as a member of the additive group.

Proof. Let (R, +, ·) be a ring so that (R, +) is its additive group.

Case 1. Let O(1) = 0 when the unity, element 1 is regarded as an element of (R, +). By the definition of the order of an element in a group, there exists no positive integer n so that n1 = 0.

∴ Characteristic of R = 0.

Case 2. Let O(1) = p(6= 0).

By the definition of the order of elements in a group, p is the least positive integer,

so p1 = 0. For any a ∈ R, pa = p(1a) = (pl)a = 0a = 0

∴ Characteristic of R = p.

For example., For the commutative ring Z× Z, the zero element = (0, 0) and the unity element = (1, 1). By the definition of the order of an element in the additive group Z × Z, there exists no positive integer m such that m(1, 1) = (m, m) = (0, 0).

Therefore, the characteristic of Z × Z is zero.

Theorem 3. The characteristic of an integral domain is either a prime or zero.

Proof. Let (R, +, ·) be an integral domain. Let the characteristic of R = p(6= 0).

If possible, suppose that p is not a prime.

Then p = mn where 1 < m, n < p. a 6= 0 ∈ R ⇒ a · a = a2 ∈ R and a2 6= 0 ( ∵ R is integral domain )

pa 2 = 0 ⇒ (mn)a 2 = 0 ⇒ (ma)(na) = 0 ⇒ ma = 0 or na = 0 ( ∵ R is integral domain )

Let ma = 0. For any x ∈ R, (ma)x = 0 ⇒ a(mx) = 0 ⇒ mx = 0 ( ∵ a 6= 0)

This is absurd, as 1 < m < p and characteristic of R = p.

∴ ma 6= 0. Similarly, we can prove that na 6= 0.

This is a contradiction and hence p is a prime.

Theorem 4. The characteristic of a field is either a prime or zero.

Proof. Since every field is an integral domain, by the above theorem the characteristic of a field is either a prime or zero.

Note.

1. The characteristic of a division ring is either a prime or zero.

2. The characteristic of Z p, where p is a prime, is p.

Rings, Integral Domains & Fields Solved Problems

Example. 2. The characteristic of an integral domain ( R, +, ·) is zero or a positive integer according as the order of any non-zero element of R regarded as a member of the group ( R, +).

Solution. Let a ∈ R and a 6= 0.

Case (1). Let O(a) = 0 when ’ a ’ is regarded as a member of (R, +).

By the definition of order, there exists no positive integer n so that na = 0.

∴ Characteristic of R = 0.

Case (2). Let O(a) = p.

By the definition of order, p is the least positive integer, so that pa = 0.

For any x ∈ R, pa = 0 ⇒ (pa)x = 0x ⇒ a(px) = 0 ⇒ px = 0 since a 6= 0.

∴ p is the least positive integer so that px = 0∀x ∈ R.

Hence characteristic of R = p.

Example. 3. If R is a non-zero ring so that a 2 = a∀a ∈ R proves that the characteristic of R = 2 or proves that the characteristic of a Boolean ring is 2.

Solution. Since a2 = a∀a ∈ R, we have (a + a)2 = a + a

⇒ (a + a)(a + a) = a + a ⇒ a(a + a) + a(a + a) = a + a

⇒ a2 + a2 + a2 + a2 = a + a ⇒ (a + a) + (a + a) = (a + a) + 0 ⇒ a + a = 0 ⇒ 2a = 0.

∴ for every a ∈ R, we have 2a = 0. Further for a 6= 0, 1a = a 6= 0.

∴ 2 is the least positive integer so 2a = 0∀a ∈ R.

Hence characteristic of R = 2.

Example. 4. Find the characteristic of the ring Z3 × Z4.

Solution.

The characteristic of the ring Z3 × Z4

We have Z3 = {0, 1, 2}, Z4 = {0, 1, 2, 3} Z3 × Z4= {(0, 0), (0, 1), (0, 2), (0, 3), (1, 0), (1, 1), (1, 2), (1, 3), (2, 0), (2, 1), (2, 2), (2, 3)} contains 12 ordered pairs as elements. Zero element (0, 0) and unity element = (1, 1)

We have, 1(1, 1) = (1, 1) ≠ (0, 0); 2(1, 1) = (2, 2) ≠ (0, 0);

3(1, 1) = (3, 3) = (0, 3)≠ (0, 0); 4(1, 1) = (4, 4) = (1, 0) ≠ (0, 0);

5(1, 1) = (5, 5) = (2, 1)≠ (0, 0); 6(1, 1) = (6, 6) = (0, 2) ≠ (0, 0);

7(1, 1) = (7, 7) = (1, 3) ≠ (0, 0); 8(1, 1) = (8, 8) = (2, 0)≠ (0, 0);

9(1, 1) = (9, 9) = (0, 1)≠ (0, 0); 10(1, 1) = (10, 10) = (1, 2)≠ (0, 0);

11(1, 1) = (11, 11) = (2, 3) ≠ (0, 0); 12(1, 1) = (12, 12) = (0, 0);

L Least positive integer = 12. Hence characteristic of Z3 × Z4 = 12.

Also, G. C. D of 3, 4 = (3, 4) = 1 ⇒ the additive group Z3 × Z4 is isomorphic with Z12

∴ Characteristic of Z3 × Z4 = Characteristic of Z12 = 12.

Example. 5. If the characteristic of a ring is 2 and the elements a, b of the ring commute prove that (a + b)2 = a2 + b2 = (a − b)2.

Solution. Since characteristic of the ring R = 2 ⇒ 2x = 0∀x ∈ R.

a, b ∈ R commute ⇒ ab = ba.

(a+ b)2 = (a+ b)(a+ b) = a(a+ b)+ b(a+ b) = a2 + ab+ ba+ b2 = a2 +2ab+ b2

a, b ∈ R ⇒ ab ∈ R and 2(ab) = 0. ( ∵ characteristic of R = 2)

(a + b)2 = a2 + 0 + b2 = a2 + b2.

Similarly, we can prove that (a − b)2 = a2+ b2.

Example. 6. If R is a commutative ring with unity of characteristic = 3 then prove that (a + b)3 = a3 + b3∀a, b ∈ R

Solution. R is a ring with characteristic = 3 ⇒ 3x = 0, zero elements of R∀x ∈ R.

Since R is a commutative ring, by Binomial Theorem, (a + b)3 = a3 +3a2b + 3ab2 + b3

a, b ∈ R ⇒ a2b, ab2 ∈ R ⇒ 3a2b = 0, 3ab2 = 0. ∴ (a + b)3 = a3 + b3.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Exercise 3

1. Prove that the characteristic of the ring Zn = {0, 1, 2, . . . , n − 1} under addition and multiplication modulo n, is n.

2. Prove that the characteristic of a field is either prime or zero.

3. Prove that the characteristic of a finite integral domain is finite.

4. Prove that any two non-zero elements of an integral domain regarded as the members of its additive group are of the same order.

5. Give examples of a field with zero characteristics and a field with characteristics.

6. Find the characteristics of the rings (1) 2Z (2) Z × Z

7. If R is a commutative ring with unity of characteristic = 4 then simplify (a + b) 4 for all a, b ∈ R.

8. If R is a commutative ring with unity of characteristic = 3 compute and simplify (1)(x + y) 6(2)(x + y) 9∀x, y ∈ R

Answers

5. Zn ring, Z5 ring

6. (1) 0 (2) 0 7. a4 + a3b + ab3 + b4

7. (1)x6 + 2x3y3 + y6 (2) x9 + y9

Rings, Integral Domains & Fields Divisibility Units, Associates And Primes In A Ring.

Definition. (Divisor or Factor) Let R be a commutative ring and a 6= 0, b ∈ R. If there exists q ∈ R such that b = aq then a’ is said to divide ’ b ’.

Notation. ’ a ’ divides ’ b ’ is denoted by a | b and a ’ does not divide ’ b ’ is denoted by aχb.

Note.

1. If ’ a ’ divides ’ b ’ then we say that a ’ is a divisor or factor of ’ b ’.

2. For a6 = 0, 0 ∈ R we have a · 0 = 0 and hence every non-zero element of a ring R is a divisor of 0 ’ 0 ’ Zero element of R.

3. a6 = 0, b ∈ R and a | b ⇔ b = aq for some q ∈ R.

For example., 1. In the ring Z of integers, 3115 and 317.

For example., 2. In the ring Q of rational numbers, 3/7 because there exists (7/3) ∈ Q such that 7 = 3.(7/3),

For example., 3. In a field F, two non-zero elements are divisors to each other.

For example., 4. In the ring Z6, 4 | 2, In the ring Z8, 3 | 7 and in the ring Z15, 9 | 12.

For example., 5. The unit of a ring R divides every element of the ring if a ∈ R is a unit then aa −1 = a−1a = 1 where a−1 ∈ R.

For any b ∈ R we have b = 1b = aa−1b = a a−1b ⇒ a | b.

Theorem. 1. If R is a commutative ring with unity and a b, c ∈ R then

- a | a (2) a | b and b|c → a|c

- a|b → a|bx∀x ∈ R

- a | b and a|c ⇒ a|bx + cy∀x, y ∈ R.

Proof.

(1) If 1 ∈ R is the unity element in R then a = a.1 which implies that a | a.

(2) a | b ⇒ b = aq1 for some q1 ∈ R; b | c ⇒ c = bq2 for some q2 ∈ R.

Now c = bq2 = (aq1) q2 = a (q1 · q2) = aq where q = q1q2 ∈ R ⇒ a | c.

(3) a | b ⇒ b = aq for some q ∈ R.

Now bx = (aq)x = a(qx) = aq1 where q1 = qx ∈ R ⇒ a | bx.

(4) a|b ⇒ a|bx∀x ∈ R; a|c ⇒ a|cy∀y ∈ R

a | bx ⇒ bx = aq1 for some q1 ∈ R; a | cy ⇒ cy = aq2 for some q2 ∈ R.

∴ bx+cy = aq1+aq2 = a (q1 + q2) = aq where q = q1+q2 ∈ R ⇒ a | (bx+cy).

Note. a | b and a|c ⇒ a|b± c. Definition. (Greatest Common Divisor G.C.D)

Let R be a commutative ring and a, b ∈ R, d ∈ R is said to be the greatest common divisor of ’ a ’ and ’ b ’ if

- d | a and d | b and

- whenever c | a and c | b

where c ∈ R then c | d. Notation. If ’ d ’ is a greatest common divisor (G. C. D) of ’ a ’ and ’ b ’ then we write d = (a, b).

Definition. (Unit) Let R be a commutative ring with unity. An element a ∈ R is said to be a unit in R if there exists an element b ∈ R such that ab = 1 in R. However, the unity element ’ 1 ’ is also a unit because 1, 1 = 1.

2. In a ring, the unity element is unique, while, units may be more than one.

3. If ab = 1 then a− 1 = b. So, a unit in a ring R is an element of the ring so its multiplicative inverse is also in the ring. That is a ∈ R is a unit of R means that the element d a is invertible.

4. Units of a ring are in fact the two divisors of the unity element in the ring.

5. ’ a ’ is a unit in R ⇒ ab = 1 for some b ∈ R ⇒ ’ b ’ is also a unit of R. example. In a field F, every non-zero element has a multiplicative inverse. So, every non-zero element in a field is a unit.

Theorem 2. Let D be an integral domain. For a, b ∈ D, if both a | b and b | a are true then a = ub where u is a unit in D.

Proof. a | b ⇒ b = aq1 for some q1 ∈ D; b | a ⇒ a = bq2 for some q2 ∈ D.

b = aq1 = (bq2) q1 = b (q2q1) ⇒ 1 = q2q1, by using cancellation property in integral domain.

∴ q2q1 = 1 ⇒ q2 is a unit in D.

Hence a = bq2 where q2 is a unit in D.

Definition. (Associates) Let R be a commutative ring with unity. Two elements ’ a ’ and ’ b ’ in R are said to be associates if b = ua for some unit u in R.

Note. The relation of being associated in a ring R is an equivalence relation in R.

For example., 1. If ’ 1 ’ is the unity element in the ring R then ’ 1 ’ is a unit in R. For a(6= 0) ∈ R we have a = 1. a and a, a are associates in R.

For example., 2. In the ring Z of integers, the units are 1 and −1 only. For a6 = 0 ∈ Z, we have a = a : 1 and a = (−a)(−1) only. Therefore, a ∈ Z has only two associates, namely, a, −a.

For example., 3. In the ring Z6 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5} of integers modulo −6, the units are 1,5 only.

For 2 ∈ Z6 ; 2 ≡ 2.1(mod6) and 2 ≡ 4.5(mod6)

∴ 2 has two associates 2,4.

Theorem. 3. In an integral domain D, two non-zero elements a, b ∈ D are associates iff a | b and b | a.

Proof. From Theorem (2) we see that a | b and b | a

⇒ there exists unit u ∈ D such that a = ub ⇒ a, b are associates. a, b are associates in D ⇒ there exists unit u in D such that a = ub ⇒ b | a. u is unit in D ⇒ there exists unit v ∈ D such that uv = 1.

Now a = ub ⇒ va = v(ub) ⇒ va = (vu)b ⇒ va = (1) b ⇒ b = va ⇒ a | b.

Hence a | b and b | a.

Definition. (Trivial Divisors and Proper Divisors)

Let a 6= 0 be an element in the integral domain D. The units in D and the associates of ’ a ’ are divisors of ’ a ’. These divisors of ’ a ’ is called Trivial divisors of ’ a ’. The remaining divisors of ’ a ’ are called the proper divisors of ’ a ’.

For example., Consider the integral domain (Z, +, ·). The units in Z are 1 and −1 only.

For a6 = 0 ∈ Z, the trivial divisors are 1, −1, a, −a only. The remaining divisors of ’ a ’ are proper divisors.

3 ∈ Z has only trivial divisors ±1, ±3 and no proper divisors.

6 ∈ Z has trivial divisors ±1, ±6 and also proper divisors ±2, ±3.

Definition. (Prime and Composite elements)

Let ’ a ’ be a non-zero and non-unit element in an integral domain D. If ’ a ’ has no proper divisors in D then ’ a ’ is called a prime element in D. If ’ a ’ has proper divisors in D then ’ a ’ is called Composite element in D.

Note. a ∈ D is a prime element and a = bc then one of b or c is a unit in D.

For example., 1. In the integral domain (Z, +, ·);

5 ∈ Z is a prime element and 6 ∈ Z is a composite element.

For example., 2. In the integral domain (Q, +, ·); 6 ∈ Q is the prime element since all its divisors are units.

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Solved Problems

Example.1. Find all the units of Z12 the ring of residue classes modulo 12.

Solutions.

We have Z12 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11}.

Clearly, the unity element = 1 is a unit. a¯ ∈ Z12 is a unit if there exists ¯b ∈ Z12 such that a¯¯b = 1.

For ~a = even there is no ¯b so that a¯¯b ≡ 1(mod12), as a¯¯b, is even. So we have to verify for a¯ = odd.

For 5 ∈ Z12 we have 5 × 5 = 1; 7 ∈ Z12 we have 7 × 7 = 1 and 11 ∈ Z12 . we have 11 × 11 = 1. ∴ 1, 5, 7, and 11 are the units in Z12

Example.2. Prove that ±1, ±i are the only four units in the domain of Gaussian integers.

Solution. Z[1] =a + ib | a,b ∈ Z, i2 = −1 is the integral domain of Gaussian integers. 1 + 0i = 1 is the unity element. Let x + iy ∈ Z[i] be a unit. By the definition, there exists u + iv ∈ Z[1] such that (x + iy)(u + iv) = 1 ⇒ |(x + iy)(u + iv)| = 1 ⇒ x2 + y2 u2 + v2 = 1

⇒ x2 = 1,y2 = 0 or x2 = 0 or y2 = 1 ⇒ x = ±1,y = 0 or x = 0,y = ±1.

∴ ±1 + 0i, 0 ± 1 i i.e., ±1; ±i are the possible units.

Example.3. Find all the associates of (2 − i) in the ring of Gaussian integers. (N. U. 97).

Solution. We have 2 − i = (2 − i) · 1; 2 − i = (−2 + i) · (−1); (2 − i) = (−2i − 1) · I and 2 − i = (2i + 1) · (−i).

∴ 2 − i, −2 + i, −2i − 1 and 2i + 1 are the associates.

Example 4. In the domain of Gaussian integers, prove that the associates of a + ib are a + ib, −a − ib, ia − b, −i a + b.

Solution.

Since ±1 and ±i are the four units of Z[1], a + ib = (a + ib).1; a + ib = (−a − ib) · (−1); a + ib = (ia − b) · (−i) and a + ib = (−i a + b) · i

∴ a + ib, −a − ib, i a − b, and −i a + b are the associates of a + ib.

Example. 5. If D is an integral domain and U is a collection of units in D, Prove that (U, ·) is a group.

Solution. (Left to the reader)

Example. 6. Find all units of Z14.

Solution.

Z14 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14} Unity element = 1 is a unit. Since 14 is even, the number in Z14 cannot be a unit.

For 3 ∈ Z14. we have 3.5 = 15 = 1 ⇒ 3, 5 are units.

For 9 ∈ Z14, we have 9.11 = 99 = 1 ⇒ 9, 11 are units.

For 13 ∈ Z14 we have 13.13 = 169 = 1 ⇒ 13 is a unit.

Example. 7. Find all the units in the matrix ring M2 (Z2)

Solution.

We have Z2 = {0, 1} so that 0 + 0 = 0, 0 + 1 = 1 + 0 = 1 and 1 + 1 = 0.

⇒ \(\mathrm{M}_2\left(\mathrm{Z}_2\right)=\left(\begin{array}{ll}a & b \\ c & d\end{array}\right) where a, b, c, d \in\{0,1\}\)

⇒ Number of elements in \(M_2\left(Z_2\right)=2^4=16\)

⇒ Clearly \(\mathrm{I}_2=\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{array}\right)\) is the unity element and hence an unit.

A ∈ M2 (Z2) is a unit in M2 if there exists a B ∈ M2 such that AB = I2 the unity element. AB = I2 happens when A is non-singular and B = A−1.

Hence the · · · its of M2 (Z2) are all the non-singular matrices. Matrices having only one ’ 0 ’ and three ’ 1 ’s are :

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0\end{array}\right)\)

which are non-singular Hence the above 4 matrices are units. Matrices having two ‘ 0 ‘s and two 1 “s are

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 1 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 0 \\

1 & 1

\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

1 & 0

\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 1 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 1 \\

1 & 0

\end{array}\right)\)

Among the above six matrices of

⇒ \(\mathrm{M}_2 ;\left(\begin{array}{cc}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{cc}0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0\end{array}\right)\)

are only nonsingular. Hence these two matrices are units.

Matrices having three ‘0’s and one ‘1 are:

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{array}\right)\)

which are all singular.

The zero matrix

⇒ \(\mathrm{O}=\left(\begin{array}{ll}0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0\end{array}\right)\)

and the matrix having all ‘l’s

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1\end{array}\right)\)

are both singular. Hence the units of

⇒ \(\mathrm{M}_2\left(\mathrm{Z}_2\right) \)are

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}0 & 1 \\ 1 & 1\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 0 \\ 1 & 1\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0\end{array}\right),\)

⇒ \(\left(\begin{array}{ll}1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1\end{array}\right)\)

⇒ \(\text { and }\left(\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 1 \\

1 & 0

\end{array}\right) \text { which are six in number. }\)

Rings, Integral Domains, And Fields Some Noncommutative Examples.

There are many rings that are not Commutative under multiplication. We study three non-commutative rings, namely, the ring of square matrices over a field, the ring of endomorphisms of an abelian group, and the Quaternions.

Rings, Integral Domains And Fields Solve Problems

Example 1. Prove that the set of all 2 × 2 matrices over the field of Complex numbers is a ring with unity under addition and multiplication of matrices.

Solution. Let \(R=\left\{\left[\begin{array}{ll}a & b \\ c & d\end{array}\right]: a, b, c, d \in \mathrm{C}\right\} be the set of 2 \times 2 matrices over \mathrm{C}\)

Let A=

⇒ \(\left[\begin{array}{ll}a_{11} & a_{12} \\ a_{21} & a_{22}\end{array}\right]=\left[a_{i j}\right]_{2 \times 2}, B=\left[\begin{array}{ll}b_{11} & b_{12} \\ b_{21} & b_{22}\end{array}\right]=\left[b_{i j}\right]_{2 \times 2} and C=\)

⇒ \([\left[\begin{array}{ll}

c_{11} & c_{12} \\

c_{21} & c_{22}

\end{array}\right]=\left[c_{i j}\right]_{2 \times 2} \)

be three elements in \mathrm{R}.

(1) A + B = [aij] 2× 2 + [bij] 2× 2 = [aij + bij] 2× 2 and

A + B = [bij + aij] 2× 2 = B + A ( ∵ aij,bij ∈ C)

∴ Addition is a binary operation and also Commutative. (2) (A + B) + C = [aij + bij] 2× 2 + [cij] 2× 2 = [(aij + bij) + cij] 2× 2 = [aij + (bij + cij)] 2× 2 = A + (B + C) ( ∵ aij,bij,cij ∈ C)

∴ Addition is associative.

⇒ (3) We have O = \(\left[\begin{array}{ll}0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0\end{array}\right]=[0]_{2 \times 2} \in \mathrm{R} such that A+\mathrm{O}=\)

⇒ \(\left[a_{i j}+0\right]_{2 \times 2}= \left.a_{i j}\right]_{2 \times 2} = A\)

= Therefore O = \(\left[\begin{array}{ll}0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0\end{array}\right]\) is the Zero element.

(4) For A − [aij] 2× 2 ,aij ∈ C ⇒ −aij ∈ C so that aij + (−aij) = o ∈ C.

∴ there exists −A = [−aij] 2× 2 ∈ R such that A+(−A) = [aij + (−aij)] 2× 2 = [0] 2× 2 = O.

∴ (R, +) is an abelian group.

(5) Let A = [aij] 2× 2 ,B = [bjk] 2× 2 ,C = [ckl] 2× 2 ∈ R.

From the definition of multiplication; AB = [aij] [bjk] = [uik] 2× 2 where uik = P2j=1 aij bjk = ai1b1k + ai2b2k ∈ C

∴ Multiplication is a binary operation.

(6) \((A B) C=\left[\sum_{j=1}^2 a_{i j} b_{j k}\right]_{2 \times 2}\left[c_{k l}\right]_{2 \times 2}\)

=\(\left[\sum_{k=1}^2\left(\sum_{j=1}^2 a_{i j} b_{j k}\right) c_{k l}\right]\)

=\(\left[\sum_{j=1}^2 a_{i j}\left(\sum_{k=1}^2 b_{j k} c_{k l}\right)\right]\)

=A(B C) therefore Multiplication is associative.

(7) \(A(B+C)=\left[a_{i j}\right]_{2 \times 2}\left[b_{j k}+c_{j k}\right]_{2 \times 2}\)

=\(\left[\sum_{j=1}^2 a_{i j}\left(b_{j k}+c_{j k}\right)\right]\)

= \(\left[\sum_{j=1}^2\left(a_{i j} b_{j k}+a_{i j} c_{j k}\right)\right]\)

= \(\left[\sum_{j=1}^2 a_{i j} b_{j k}\right]+\left[\sum_{j=1}^2 a_{i j} c_{j k}\right]=A B+A C\)

Similarly, we can prove that (B + C)A = BA + CA. ∴ Distributive laws hold.

Hence (R, +, ·) is a ring

⇒ \(\text { Since } 1 \in \mathrm{C}, I=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right] \in \mathbb{R} \text {. For } A\)

⇒ \(=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

a_{11} & a_{12} \\

a_{21} & a_{22}

\end{array}\right]_{2 \times 2}\)

⇒ \(A I=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

a_{11}+0 & 0+a_{12} \\

a_{21}+0 & 0+a_{22}

\end{array}\right]_{2 \times 2}=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

a_{11} & a_{12} \\

a_{21} & a_{22}

\end{array}\right] \) = A. Also IA = A.

⇒ \(\left[\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right] \)

⇒ \(

\text { Let } A=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 2 \\

3 & 4

\end{array}\right] \text { and } B=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

2 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right] \text {. }\) Then AB =

⇒ \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

2+0 & 0+2 \\

2+0 & 0+2

\end{array}\right]=\)

⇒ \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

2 & 2 \\

6 & 4

\end{array}\right]

\)

and BA =\(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

2+0 & 4+0 \\

0+4 & 0+4

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

2 & 4 \\

4 & 4

\end{array}\right] \)

so that AB 6= BA

Hence (R, +, ·) is not a commutative ring.

Notation. The ring of all 2 × 2 matrices over the field of complex numbers C is denoted by M2(C). If F is a field the ring of all n × n matrices over F is denoted M n( F). The zero element in Mn( F) is denoted by O·n× n and the unity element by I

Zero divisors in M2(C) : A =

⇒ \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 1 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right] \neq \mathrm{O} \text { and } B=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right] \neq \mathrm{O}\)

Then AB = \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 1 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right] \neq \mathrm{O} \text { and } B A=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 0 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]=\mathrm{O}

\)

We observe that AB 6= BA and A6 = O, B6 = O ⇒ BA = O. Therefore there exist Zero divisors in M2(F) where F is a field.

Nilpotent element in M2(C) :

For A = \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 2 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]

\)

we have A2 = \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 2 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 2 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 0 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]=\mathrm{O} \)

Therefore A is a nilpotent matrix in M2(C).

⇒ \( B=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1 & 1 \\

-1 & -1

\end{array}\right]\) is also a nilpotent matrix element in M2(C).

Example.2. The set of 2 × 2 matrices of the form

⇒ \(

\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x & y \\

-\bar{y} & \bar{x}

\end{array}\right]

\)

where x, y are complex numbers and x,¯ y¯ denote the complex conjugates of xy; is a skew field for compositions of matrix addition and multiplication.

Solution. Let M =\(

\left\{\left[\begin{array}{cc}

\frac{x}{-y} & \bar{x}

\end{array}\right]: x=a+i b, y=c+i d ; a, b, c, d \in \mathrm{R}\right\} \) be the set

of 2 × 2 matrices.

⇒ \(

\text { Let } A=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_1 & y_1 \\

-y_1 & \bar{x}_1

\end{array}\right], B=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_2 & y_2 \\

-y_2 & \bar{x}_2

\end{array}\right], C=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_3 & y_3 \\

-y_3 & \overline{x_3}

\end{array}\right] \in \mathrm{M} \)

⇒ \(

\text { (1) } A+B=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_1+x_2 & y_1+y_2 \\

-\bar{y}_1-\bar{y}_2 & \overline{x_1}+\bar{x}_2

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_1+x_2 & y_1+y_2 \\

-\overline{y_1+y_2} & \underline{x_1+x_2}

\end{array}\right] \in \mathrm{M} \text {, since }

\)

¯Z1 ± Z2 = Z¯1 ± Z¯2 for Z¯1, Z¯2 ∈ C

⇒ \(

\text { A. } B=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

x_1 & y_1 \\

-y_1 & \bar{x}_1

\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_2 & y_2 \\

-y_2 & -x_2

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x_1 x_2-y_1 y_2 & x_1 y_2+y_1 x_2 \\

-y_1 x_2-x_1 y_2 & -y_1 y_2+x_1 x_2

\end{array}\right]\)

If u = x1x2 − y1y¯2 and ν = x1y2 + y1x¯2 then u = ¯x1x¯2 − y¯1y2 and v¯ = x¯1y¯2 + ¯y1x2

A,B =\(

\left[\begin{array}{cc}

u & v \\

-\bar{v} & \bar{u}

\end{array}\right] \in \mathrm{M}

\)

Hence addition ( + ) and multiplication

(1) are binary operations.

(2) Clearly A + B = B + A for any A,B ∈ M.

(3) Clearly (A + B) + C = A + (B + C) and (A,B) · C = A(B,C) for any A,B,C ∈ M because addition and multiplication of matrices are associative.

(4) There exists O =

⇒ \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 0 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

0+i 0 & 0+i 0 \\

-0+i 0 & 0+i 0

\end{array}\right] \in

\)

M so that A +O = A for any A ∈ M.

(5) For A =\(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

x & y \\

-y & \bar{x}

\end{array}\right] \text { there exists }-A=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

-x & -y \\

\bar{y} & -x

\end{array}\right] \text { so that } A+(-A)=

\)

⇒ \(

\left[\begin{array}{ll}

0 & 0 \\

0 & 0

\end{array}\right]=0

\)

= 0 (Zero matrix)

(6) For any A,B,C ∈ M, distributive laws, namely, A· (B+C) = A·B+A·C

and (B + C) · A = B · A + C · A are clearly true. Hence (M, +, −) is a ring

⇒ \(

\text { (7) We have } I=\left[\begin{array}{ll}

1 & 0 \\

0 & 1

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

1+i 0 & 0+i 0 \\

-0+i 0 & \frac{1+i \cdot 0}{1+}

\end{array}\right] \in \text { so that } A \cdot I=I \cdot A=A \text { for any } A \in \mathrm{M} \text {. }

\)

∴ the ring M has unity element I.

(8) Let A 6= 0 ∈ M so that A =\(

\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x & y \\

-y & \bar{x}

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}

a+i b & c+i d \\

-c+i d & a-i b

\end{array}\right]

\)

where a,b,c,d are not all zero.

Det A = (a + ib)(a − ib) − (c + id)(−c + id) = a2 + b2 + c2 + d2 6= 0

Since det A 6= 0, A 6= O is invertible. Hence (M, +, ·) is a skew field.

Note. The matrix \(

\left[\begin{array}{cc}

x & y \\

-y & \bar{x}

\end{array}\right] \text { is also given as }\left[\begin{array}{cc}

a+i b & c+i d \\

-c+i d & a-i b

\end{array}\right]

\) in the problem.

Rings, Integral Domains & Fields Ring Of Quaternions

Example 3. Prove that the set of Quaternions is a skew field.

Solution. Let Q = R × R × R × R = {α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k | α0,α1,α2,α3 ∈ R} where i,j,k are quaternion units satisfying the relations :

i 2 = j2 = k 2 = i · jk = −1, ij = −ji = k, jk = −kj = i, ki = −ik = j. Let

X, Y, Z ∈ Q so that X = α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k, Y = β0 + β1i + β2j + β3k and Z = γ0 + γ1i + γ2j + γ3k where αt, βt, γt for t = 0, 1, 2, 3 are real numbers.

We define X = Y ⇔ αt = βt for t = 0, 1, 2, 3.

We define addition (+) as X + Y = (α0 + β0) + (α1 + β1) i + (α2 + β2) j +

(α3 + β3) k and multiplication (·) as X.Y = ( α0β0− α1β1 − α2β2 − α3β3) + (α0β1 + α1β0 + α2β3 − α3β2) i

+ (α0β2 + α2β0 + α3β1 − α1β3) j + (α0β3 + α3β0 + α1β2 − α2β1) k.

(1) ∀X, Y ∈ Q; X + Y = (α0+ β0) + (α1+ β1) i + (α2 + β2) j + (α3 + β3) k

As αt + βt for t = 0, 1, 2, 3 ∈ R, X + Y ∈ Q. ∴ addition (+) is a binary operation.

(2) ∀X, Y ∈ Q; X + Y = (α0+ β0) + (α1+ β1) i + (α2 + β2) j + (α3 + β3) k

= (β0 + α0) + (β1 + α1) i + (β2 + α2) j + (β3 + α3) k˙ = Y + X

∴ addition is commutative:

( ∵ αt + βt = βt + αt for t = 0, 1, 2, 3) .

(3) ∀X, Y, Z ∈ Q

(X + Y) + Z = {(α0 + β0) + (α1 + β1) i + (α2 + β2) j + (α3 + β3) k} + (γ0 + γ1i + γ2j + γ3k)

= [(α0 + β0) + γ0] + [(α1 + β1) + γ1] i + [(α2 + β2) + γ2] j + [(α3 + β3) + γ3] k

= [α0 + (β0 + γ0)] + [α1 + (β1 + γ1)] i + [α2 + (β2 + γ2)] j + [α3 + (β3 + γ3)] k

= X + (Y + Z). ( ∵ (αt + βt) + γt = αt + (βt + γt) for t = 0, 1, 2, 3) .

∴ addition is associative.

(4) For O = 0 + 0i + 0j + 0k ∈ Q and X = α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k we have

O + X = (0 + α0) + (0 + α1) i + (0 + α2) j + (0 + α3) k = α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k =

X = X + O

∴ O = 0 + 0i + 0j + 0k is the additive identity.

(5) For X = α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k there exists −X = (−α0) + (−α1) i +

(−α2) j + (−α3) k ∈ Q such that X + (−X) = [α0 + (−α0)] + [α1 + (−α1)] i +

[α2 + (−α2)] j + [α3 + (−α3)] k = 0 + 0i + 0j + 0k = 0, the additive identity.

∴ every element has an additive inverse.

Hence, from (1), (2), (3), (4) and (5) : (Q, +) is abelian group.

(6) X.Y = b0 + b1i + b2j + b3k where b0 = α0β0 − α1β1 − α2β2 − α3β3

b1 = α0β1 + α1β0 + α2β3 − α3β2, b2 = α0β2 + α2β0 + α3β1 − α1β3

and b3 = α0β3 + α3β0 + α1β2 − α2β1 are real numbers.

∴ multiplication (·) is a binary operation.

(7) (X : Y) · Z = (b0 + b1i + b2j + b3k) · (γ0 + γ1i + γ2j + γ3k)

= (b0γ0 − b1γ1 − b2γ2 − b3γ3) + (b0γ1 + b1γ0 + b2γ3 − b3γ2) i + (b0γ2 + b2γ0 + b3γ1 − b1γ3) j

+ (b0γ3 + b3γ0 + b1γ2 − b2γ1) k

Y.Z = c0 + c1i + c2j + c3k where c0 = β0γ0 − β1γ1 − β2γ2 − β3γ3,

c1 = β0γ1 + β1γ0 + β2γ3 − β3γ2,

c2 = β0γ2 + β2γ0 + β3γ1 − β1γ3,

c3 = β0γ3 + β3γ0 + β1γ2 − β2γ1.

X.(Y.Z) = (α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k) . (c0 + c1i + c2j + c3k)

= (α0c0 − α1c1 − α2c2 − α3c3) + (α0c1 + α1c0 + α2c3 − α3c2) i

+ (α0c2 + α2c0 + α3c1 − α1c3) j + (α0c3 + α3c0 + α1c2 − α2c1) k

Since the corresponding terms of (X.Y). Z and X.(Y, Z) are equal we have

∴ multiplication is associative.

(8) Both the distributive laws, namely, X.(Y + Z) = X.Y + X.Z and (Y + Z) · X = Y · X + Z · X can be proved to be true.

From the truth of the above 8 properties, we establish that (Q+, ·) is a ring.

(9) There exists 1 = 1 + 0i + 0j + 0k ∈ Q such that

∀X ∈ Q we have 1.X = (1 + 0i + 0j + 0k) · α0˙ + α1i + α2j + α3k

= (1.α0 − 0.α1 − 0.α2 − 0.α3) + (1.α1 + α0 · 0 + 0.α3 − 0.α2) i

+ (1.α2 + 0.α0 + 0.α1 − α1 · 0) j + (1 · α3 + 0.α0 + 0 · α2 − 0.α1) k

= α0 + α1i + α2j + α3k = X. Also X.1= X.

∴ 1 = 1 + 0i + 0j + 0k ∈ Q is the unity element.

(10) Let X 6= 0, the zero element. Then not all α0, α1, α2, α3 are zero ∈ R.

∴ α20 + α2 1+ α22 + α23 = ∆ ≠0 ∈ R.

For the real numbers α 0

⇒ \(

\frac{\alpha_0}{\Delta}, \frac{-\alpha_1}{\Delta}, \frac{-\alpha_2}{\Delta}, \frac{-\alpha_3}{\Delta}

\) there exists

⇒ \(

\mathrm{X}^1=\frac{\alpha_0}{\Delta}-\frac{\alpha_1}{\Delta} i-\frac{\alpha_2}{\Delta} j-\frac{\alpha_3}{\Delta} k \in \mathrm{Q} . \quad \text { Further } \mathrm{X} \cdot \mathrm{X}^1=\left(\frac{\alpha_0^2}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_1^2}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_2^2}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_3^2}{\Delta}\right)

\)

⇒ \(

+\left(\frac{-\alpha_0 \alpha_1}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_0 \alpha_1}{\Delta}-\frac{\alpha_2 \alpha_3}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_3 \alpha_2}{\Delta}\right) i+\left(\frac{-\alpha_0 \alpha_2}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_2 \alpha_0}{\Delta}-\frac{\alpha_3 \alpha_1}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_1 \alpha_3}{\Delta}\right) j

\)

⇒ \(

+\left(\frac{-\alpha_0 \alpha_3}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_3 \alpha_0}{\Delta}-\frac{\alpha_1 \alpha_2}{\Delta}+\frac{\alpha_2 \alpha_1}{\Delta}\right)

\)

k = 1 + 0i + 0j + 0k = 1, the unity element.

Similarly, we can prove that X1 · X = 1.

We have X.Y = (α0β0 − α1β1 − α2β2 − α3β3)+(α0β0 + α1β0 + α2β3 − α3β2) i

+ (α0β2 + α2β0 + α3β1 − α1β3) j + (α0β3 + α3β0 + α1β2 − α2β1) k

= b0 + b1i + b2j + b3k and

∴ every non-zero element of Q has a multiplicative inverse.