Laplace Transform Exercise 2

1. If F(t) is continuous for all t≥0 and of exponential order a as t→∞ and if ⋅F^’ (t) is of class A, then prove that the Laplace transform of F'(t) exists when p>a and L[F'(t)]=pf(p)-F(0) where L[F(t)]=f(p).

Solution:

If F(t) is continuous for all t≥0 and of exponential order a as t→∞ and if ⋅F^’ (t) is of class A

L\(\left[F^{\prime}(t)\right]=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} d[F(t)]=\left[e^{-p t} F(t)\right]_0^{\infty}+\int_0^{\infty} p e^{-p t} F(t) d t\)

= \(0-F(0)+p \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \cdot F(t) d t\) (because F(t) is exponential order)

∴ \(L\left[F^{\prime}(t)\right]=p L[F(t)]-F(0)=p f(p)-F(0)\)

2. Prove that \(L\left[F^{\prime \prime}(t)\right]=p^2 f(p)-p f(0)-F^{\prime}(0)\).

Solution:

L\(\left[F^{\prime \prime}(t)\right]=L\left[\left(F^{\prime}(t)\right)^{\prime}\right]=p L\left[F^{\prime}(t)\right]-F^{\prime}(0)=p \cdot[p L(F)-F(0)]-F^{\prime}(0)\)

= \(p^2 L F(t)-p f(0)-F^{\prime}(0)\)

3. Prove that \(L\left\{F^{(n)}(t)\right\}=p^n f(p)-p^{n-1} F(0)-p^{n-2} F^{\prime}(0) \cdots F^{(n-1)}(0)\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=e^{-p t} F(t)_0^{\infty}-\int_0^{\infty} F(t) e^{-p t}(-p) d t\)

= \(-F(0)+p \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=p f(p)-F(0)\)

Suppose \(L\left\{F^{(m)}(t)\right\}=p^m f(p)-p^{m-1} F(0)-p^{m-2} F^{\prime}(0) \cdots F^{(m-1)}(0)\)

⇒ \(\left.L\left\{F^{(m+1)}(t)\right\}=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{(m+1)}(t) d t=e^{-p t} F^{(m)}(t)\right]_0^{\infty}-\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}(-p) F^{(m)}(t) d t\)

= \(-F^{(m)}(0)+p \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{(m)}(t) d t=-F^{(m)}(0)+p L\left\{F^{(m)}(t)\right\}\)

= \(-F^{(m)}(0)+p^{m+1} f(p)-p^m F(0)-p^{m-1} F^{\prime}(0)-\cdots-p F^{(m-1)}(0)\)

= \(p^{m+1} f(p)-p^m F(0)-p^{m-1} F^{\prime}(0) \cdots-p F^{(m-1)}(0)-F^{(m)}(0)\)

∴ If the statement is true for n=m then it is true for n=m+1

Hence by induction, \(L\left\{F^{(n)}(t)\right\}=p^n f(p)-p^{n-1} F(0)-p^{n-2} F^{\prime}(0)-\cdots-F^{(n-1)}(0)\).

Advanced Laplace Transform Solved Examples Step-By-Step

4. State and prove the initial value theorem.

Solution:

Initial value theorem

Statement: If F(t) is peicewise continuous for all \(t \geq 0\) and of exponential order as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) or \(F^{\prime}(t)\) is of class A, then Lt F(t) = \(\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{\text{Lt}} p t\{f(t)\}=\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{\text{Lt}}[p f(p)]\).

Proof: By the theorem on the Laplace transform of derivatives we have

L \(\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=p L(F(t)]-F(0) \rightarrow(1)\)

Since \(F^{\prime}(t)\) is piecewise continuous and of exponential order, we have \(\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{L t} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=0\)

(because \(\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{L t} \int_0^{\infty} e_0^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=\int_0^{\infty}\left(\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{L t} e^{-p t}\right) F^{\prime}(t) d t=\int_0^{\infty}(0) F^{\prime}(t) d t=0\)

Taking limit as \(p \rightarrow \infty\) in (1), we have \(0=\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{\text{Lt}} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0)\)

⇒ \(F(0)=\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{\text{Lt}} p \dot{L}\{F(t)\} \Rightarrow \underset{t \rightarrow 0}{\text{Lt}} F(t)=\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{\text{Lt}} p L\{F(t)\}=\underset{p \rightarrow \infty}{\text{Lt}} p F(p)\)

5. State and prove the final value theorem.

Solution:

Final value theorem

Statement: If F(t) is continuous for all \(t \geq 0\) and of exponential order as \(t \rightarrow \infty\) or \(F^{\prime}(t)\) is of class A, then

Lt F(t) = \(\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{\text{Lt}} p L\{F(t)\}=\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{\text{Lt}}[p f(p)]\).

Proof: By a theorem of Laplace transform on derivatives, we have

L\(\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=L_{p \rightarrow 0} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0) \rightarrow(1)\)

Taking limit as \(p \rightarrow 0\) in (1), we have \(\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{L} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F^{\prime}(t) d t=\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{L t} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0)\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty}\left(L_{p \rightarrow 0}^{L t} e^{-p t}\right) F^{\prime}(t) d t=L_{p \rightarrow 0} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0)\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} F^{\prime}(t) d t=\mathrm{Lt}_{p \rightarrow 0} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0)\)

⇒ \(F[(t)]_0^{\infty}=\text{Lt}_{p \rightarrow 0} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0) \Rightarrow \underset{t \rightarrow \infty}{\\text{Lt}} F(t)-F(0)\)

= \(\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{\text{Lt}} p L\{F(t)\}-F(0)\)

∴ \(\mathrm{Lt}_{t \rightarrow \infty} F(t)=\underset{p \rightarrow 0}{L t} p L\{F(t)\}=\mathrm{Lt}_{p \rightarrow 0} p f(p)\)

6. Find the Laplace transform of \(e^{a t}\) using the theorem on transforms of derivatives.

Solution:

Let \(F(t)=e^{a t} \text {. Then } F^{\prime}(t)=a e^{a t} \text { and } F(0)=1\)

Now, \(L\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=p L\{F(t)\}-F(0) \Rightarrow L\left\{a e^{a t}\right\}=p L\left\{e^{a t}\right\}-1\)

⇒ \(a L\left\{e^{a t}\right\}-p L\left\{e^{a t}\right\}=-1 \Rightarrow(a-p) L\left\{e^{a t}\right\}=-1 \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{a t}\right\}=\frac{-1}{a-p}=\frac{1}{p-a}\)

Laplace Transform II Exercise Problems With Solutions

7. Find the Laplace transform of cos at using the theorem on transforms of derivatives.

Solution:

Let F(t)=cos a t.

Then \(F^{\prime}(t)=-a \sin a t, F^{\prime \prime}(t)=-a^2 \cos a t\)

∴ \(L\left\{F^{\prime \prime}(t)\right\}=p^2 L\{F(t)\}-p F(0)-F^{\prime}(0) \rightarrow(1)\)

Now \(F(0)=\cos 0=1\) and \(F^{\prime}(0)=-a \sin 0=0\).

Substituting in (1), we get \(L\left\{-a^2 \cos a t\right\}=p^2 L\{\cos a t\}-p(1)-0\)

⇒ \(\left(p^2+a^2\right) L\{\cos a t\}=p \Rightarrow L\{\cos a t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\)

8. Find the Laplace transform of t sin at using the theorem on transforms of derivatives.

Solution:

Let F(t) = t sin at.

Then \(F^{\prime}(t)=\sin a t+a t c o s\) at and \(F^{\prime \prime}(t)=a \cos a t+a[\cos a t-a t \sin a t]=2 a \cos a t-a^2 t \sin a t\)

Also \(F(0)=0\) and \(F^{\prime}(0)=0\)

Now\(L\left\{F^{\prime \prime}(t)\right\}=p^2-L\{F(t)\}-p F(0)-F^{\prime}(0)\)

⇒ \(L\left\{2 a \cos a t-a^2 t \sin a t\right\}=p^2 L\{t \sin a t\}-0-0\)

⇒ \(2 a L\{\cos a t\}-a^2 L\{t \sin a t\}-p^2 L\{t \sin a t\}=0\)

⇒ \(2 a L\{\cos a t\}-\left(a^2+p^2\right) L\{t \sin a t\}=0\)

⇒ \(\frac{2 a p}{p^2+a^2}=\left(a^2+p^2\right) L\{t \sin a t\} \Rightarrow L\{t \sin a t\}=\frac{2 a p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\)

9. If \(L\left[2 \sqrt{\frac{t}{\pi}}\right]=\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\), then show that \(L\left\{\frac{1}{\sqrt{t \pi}}\right\}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{p}}\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\left[2 \sqrt{\frac{t}{\pi}}\right]=\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\)Let \(F(t)=2 \sqrt{\frac{t}{\pi}} \text {. Then } F^{\prime}(t)=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \cdot \frac{1}{2 \sqrt{t}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi t}} \text { and } F(0)=0\)

Now, \(L\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=p L\{F(t)\}-F(0) \Rightarrow L\left\{\frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi} t}\right\}=p L\left\{2 \sqrt{\frac{t}{\pi}}\right\}-0=p\left(\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\right)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{p}}\)

10. If \(L[\sin \sqrt{t}]=\frac{\sqrt{\pi} e^{1 / 4 p}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\), then find \(L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{\sqrt{t}}\right\}\).

Solution:

Given

\(L[\sin \sqrt{t}]=\frac{\sqrt{\pi} e^{1 / 4 p}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\)Let \(F(t)=\sin \sqrt{t} \text {. Then } F^{\prime}(t)=\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{t}} \cos \sqrt{t} \text {. Also } F(0)=0\)

Now, \(L\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=p L\{F(t)\}-F(0) \Rightarrow L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{2 \sqrt{t}}\right\}=p L\{\sin \sqrt{t}\}-0\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2} L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{\sqrt{t}}\right\}=p \frac{\sqrt{\pi} e^{-1 /(4 p)}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}=\frac{\sqrt{\pi} e^{-1 /(4 p)}}{2 p^{1 / 2}} \Rightarrow L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{\sqrt{t}}\right\}=\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{p}} e^{-1 /(4 p)}\)

11. Find \(L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{\sqrt{t}}\right\}\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\sin \sqrt{t}=\sqrt{t}-\frac{(\sqrt{t})^3}{3!}+\frac{(\sqrt{t})^5}{5!}-\frac{(\sqrt{t})^7}{7!}+\cdots=t^{1 / 2}-\frac{t^{3 / 2}}{3!}+\frac{t^{5 / 2}}{5!}-\frac{t^{7 / 2}}{7!}+\cdots\)

∴ \(L\{\sin \sqrt{t}\}=L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}-\frac{1}{3!} L\left\{t^{3 / 2}\right\}+\frac{1}{5!} L\left\{t^{5 / 2}\right\}-\frac{1}{7!} L\left\{t^{7 / 2}\right\}+\cdots\)

= \(\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)}{p^{3 / 2}}-\frac{1}{3!} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{5}{2}\right)}{p^{5 / 2}}\)

+ \(\frac{1}{5!} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{7}{2}\right)}{p^{7 / 2}}-\frac{1}{7!} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{9}{2}\right)}{p^{9 / 2}}+\cdots\)

∴ \(L\left\{t^n\right\}=\frac{\Gamma(n+1)}{p^{n+1}}\)

= \(\frac{\frac{1}{2} \Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}{p^{3 / 2}}-\frac{1}{3!} \frac{\frac{3}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \Gamma \cdot\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}{p^{5 / 2}}+\frac{1}{5!} \frac{\frac{5}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}{p^{7 / 2}}\)

–\(\frac{1}{7!} \frac{\frac{7}{2} \cdot \frac{5}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)}{p^{9 / 2}}+\cdots\)

= \(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\left[1-\frac{3}{2 \cdot 3!p}+\frac{5 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 5!p^2}-\frac{7 \cdot 5 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 \cdot 7!p^3}+\cdots\right]\)

because \(\Gamma\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)=\sqrt{\pi}\)

= \(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\left[1-\frac{1}{2^2} p+\frac{1}{\left(2^2 p\right)^2 2!}-\frac{1}{\left(2^2 p\right)^3 3!}+\cdots\right]=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\left(e^{\left.-1 / 2^2 p\right)}\right)=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 p^{3 / 2}} e^{-1 / 4 p} \text {. }\)

Let \(F(t)=\sin \sqrt{t}\). Then \(F^{\prime}(t)=\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{t}} \cos \sqrt{t}\). Also F(0)=0

Now \(L\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=p L\{F(t)\}-F(0) \Rightarrow L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{2 \sqrt{t}}\right\}=p L\{\sin \sqrt{t}\}-0\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2} L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{\sqrt{t}}\right\}=p \frac{\sqrt{\pi} e^{-1 /(4 p)}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}=\frac{\sqrt{\pi} e^{-1 /(4 p)}}{2 p^{1 / 2}}\)

⇒ \(L\left\{\frac{\cos \sqrt{t}}{\sqrt{t}}\right\}=\sqrt{\frac{\pi}{p}} e^{-1 /(4 p)}\)

Solved Problems On Laplace Transform For Advanced Exercises

12. If F(t) is piecewise continuous and of exponential order, then show that the Laplace transform of \(\int_0^t F(t) d t \text { is } \frac{1}{p} L[F(t)] \text { i.e., } L\left[\int_0^t F(t) d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} L[F(t)]\)

Solution:

Given

F(t) is piecewise continuous and of exponential order

L\(\left[\int_0^t F(t) d t\right]=\int_0^{\infty}\left[\int_0^t F(t) d t\right] e^{-p t} d t=\int_0^{\infty}\left[\int_0^t F(t) d t\right] d\left(\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p}\right)\)

= \(\left[\frac{e^{-p p t}}{-p} \int_0^t F(t) d t\right]+\frac{1}{p} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\frac{1}{p} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t\)

∴ \(L\left[\int_0^t F(t) d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} L[F(t)]\)

13. Find the Laplace transform of \(\int_0^t e^{-t} \cos t d t\).

Solution:

We know that \(L\{\cos t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

L\(\left\{e^{-t} \cos t\right\}=\frac{p+1}{(p+1)^2+1}=\frac{p+1}{p^2+2 p+2}\)

∴ \(L\left[\int_0^t e^{-t} \cos t d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} L\left(e^{-t} \cos t\right)=\frac{1}{p} \frac{p+1}{p^2+2 p+2}\)

14. Find the Laplace transform of \(\int_0^t e^{-t} \sinh t d t\)

Solution:

We know that \(L\{\sinh t\}=\frac{1}{p^2-1} \text {. }\)

L\(\left\{e^{-t} \sinh t\right\}=\frac{1}{(p+1)^2-1}=\frac{1}{p^2+2 p}\)

∴ \(L\left[\int_0^t e^{-t} \sinh t d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} L\left(e^{-t} \sinh t\right)=\frac{1}{p} \frac{1}{p^2+2 p}=\frac{1}{p^2(p+2)}\)

15. Find the Laplace transform of \(\int_0^t \int_0^t \cosh a t d t\).

Solution:

We know that \(L\{\cosh a t\}=\frac{p}{p^2-a^2}\)

L\(\left[\int_0^t \cosh a t\right]=\frac{1}{p} f(p)=\frac{1}{p}\left(\frac{p}{p^2-a^2}\right)=\frac{1}{p^2-a^2} .\)

∴ \(\int_0^t \int_0^t \cosh a t d t=\frac{1}{p}\left(\frac{1}{p^2-a^2}\right)=\frac{1}{p\left(p^2-a^2\right)}\)

Inverse Laplace Transform II Examples With Solutions

16. If f(t) is a function of class A and if L{f(t)}=f(p) prove that \(L\{t f(t)\}=-f^{\prime}(p)\).

Solution:

Given

f(t) is a function of class A and if L{f(t)}=f(p)

f(p) = \(L\{F(t)\}=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t\)

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=\frac{d}{d p} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\partial}{\partial p}\left[e^{-p t} F(t)\right] d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}(-t) F(t) d t\)

= \(-\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t F(t) d t=-L\{t F(t)\}\)

∴ \(L\{t F(t)\}=-\frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]\)

17. If L{F(t)}=f(p) then show that \(L\left\{t^n F(t)\right\}=(-1)^n \frac{d^n}{d p^n}[f(p)], n=1,2,3 \ldots\).

Solution:

We prove \(L\left\{t^n F(t)\right\}=(-1)^n \frac{d^n}{d p^n} f(p) \rightarrow(1)\) by Inductic on n.

f(p) = \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t \Rightarrow \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=\frac{d}{d p} \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\partial}{\partial p}\left[e^{-p t} F(t)\right] d t\)

= \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}(-t) F(t) d t \stackrel{=}{=}-\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t F(t) d t=-L\{t F(t)\}\)

∴ \(L\{t F(t)\}=-\frac{d}{d p}[f(p)] \Rightarrow(1)\) is true for n=1.

Assume that (1) is true for n=m.

Now \(\frac{d}{d p}\left[L\left\{t^m F(t)\right\}\right]=(-1)^m \frac{d^{m+1}}{d p^{m+1}}[f(p)]\)

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d p}\left(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t^m F(t) d t\right)=(-1)^m \cdot \frac{d^{m+1}}{d p^{m+1}}[f(p)]\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{d}{d t}\left(-e^{-p t} t t^m F(t)\right) d t=(-1)^m \frac{d^{m+1}}{d p^{m+1}}[f(p)]\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(-t^{m+1}\right) F(t) d t=(-1)^m \frac{d^{m+1}}{d p^{m+1}}[f(p)]\)

⇒ \(-L\left\{t^{m+1} F(t)\right\}=(-1)^m \frac{d^{m+1}}{d p^{m+1}}[f(p)] \Rightarrow L\left\{t^{m+1} f(p)\right\}=(-1)^{m+1} \frac{d^{m+1}}{d p^{m+1}}[f(p)]\)

Thus (1) is ture for n=m+1.

By mathematical induction \(L\left\{t^n F(t)\right\}=(-1)^n \frac{d^n}{d t^n}[f(p)] \forall n \text {. }\)

18. Find \(L[t \sin a t]\).

Solution:

We have \(L[\sin a t]=\frac{a}{p^2+a^2}=f(p) \text { (say) }\)

∴ \(L[t \sin a t]=–\frac{d}{d p}\left[f^{\prime}(p)\right]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{a}{p^2+a^2}\right]=\frac{2 a p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\)

19. Evaluate \(L\{t \cos a t\}\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\{t \cos a t\}\)Since \(L\{\cos a t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}=f(p)\)

∴ \(L\{t \cos a t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\right\}=(-1)\left[\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right) 1-(2 p)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{p^2-a^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\)

Applications Of Laplace Transform Ii In Engineering And PhysicsApplications Of Laplace Transform Ii In Engineering And Physics

20. Find \(L\{t \cos t\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{\cos t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+1}=f(p)\)

∴ \(L\{t \cos t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right\}=(-1)\left[\frac{\left(p^2+1\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{p^2-1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\)

21. Evaluate \(L\{\sin a t-a t \cos a t\}\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\{\sin a t-a t \cos a t\}\)L\(\{\sin a t-a t \cos a t\}=L\{\sin a t\}-a L\{t \cos a t\}=\frac{a}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{a\left(p^2-a^2\right)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\)

= \(\frac{a\left(p^2+a^2\right)+a^3-a p^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}=\frac{2 a^3}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2} .\)

22. Find the Laplace transform of \(L\{t(3 \sin 2 t-2 \cos 2 t)\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{3 \sin 2 t-2 \cos 2 t\}=3 L\{\sin 2 t\}-2 L\{\cos 2 t\}\)

= \(3 \cdot \frac{2}{p^2+4}-2 \cdot \frac{p}{p^2+4}=\frac{6-2 p}{p^2+4}\)

L\(\{t(3 \sin 2 t-2 \cos 2 t)\}=\frac{-d}{d p}\left\{\frac{6-2 p}{p^2+4}\right\}\)

= \(-\frac{\left[\left(p^2+4\right)(-2)-2 p(6-2 p)\right]}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}=\frac{12 p+8-2 p^2}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\)

Laplace Transform II Detailed Examples And Solutions

23. Find \(L\left(t \sin ^2 t\right)\).

Solution:

L\(\left(\sin ^2 t\right)=L\left[\frac{1-\cos 2 t}{2}\right]=\frac{1}{2}[L(1)-L(\cos 2 t)]=\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+4}\right]\)

= \(\frac{4}{2 p\left(p^2+4\right)}=\frac{2}{p\left(p^2+4\right)}\)

∴ \(L\left[t \sin ^2 t\right]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{2}{p\left(p^2+4\right)}\right]=-\left[\frac{p\left(p^2+4\right) \cdot 0-2 \cdot\left(3 p^2+4\right)}{\left[p\left(p^2+4\right)\right]^2}\right]=\frac{6 p^2+8}{p^2\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\)

24. Evaluate \(L[t \sin 3 t \cos 2 t]\).

Solution:

Given

\(L[t \sin 3 t \cos 2 t]\)We have \(L\{\sin 3 t \cos 2 t\}=\frac{1}{2} L\{2 \sin 3 t \cos 2 t\}=\frac{1}{2} L\{\sin 5 t+\sin t\}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{5}{p^2+25}+\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right]=f(p)\)

∴ \(L[t \sin 3 t \cos 2 t]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=-\frac{1}{2} \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{5}{p^2+25}+\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right]\)

= \(-\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{-10 p}{\left(p^2+25\right)^2}-\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right]=\frac{5 p}{\left(p^2+25\right)^2}+\frac{p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\)

Worked Examples On Laplace Transform II For Differential Equations

25. Find \(L\left\{t^2 \sin t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{\sin t\}=\frac{1}{p^2+1}\)

L\(L\left\{t^2 \sin t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}[L\{\sin t\}]=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right\}=\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{-1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}(2 p)\right\}\)

= \(-\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}=-\left[\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^2 2-2 p 2\left(p^2+1\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\right]\)

= \(-\left[\frac{2\left(p^2+1\right)-8 p^2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3}\right]=\frac{6 p^2-2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3}\)

26. Find \(L\left\{t^2 \cos t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{\cos t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

L\(\left\{t^2 \cos t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2} L\{\cos t\}=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right\}=\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{\left(p^2+1\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{1-p^2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}=\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^2(-2 p)-\left(1-p^2\right) 2\left(p^2+1\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)(-2 p)-4 p\left(1-p^2\right)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3}=\frac{2 p^3-6 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3} .\)

27. Find \(L\left\{t^2 \cos a t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{t^2 \cos a t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}[L\{\cos a t\}]=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left[\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\right]=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{a^2-p^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\right]=\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2(-2 p)-\left(a^2-p^2\right) 2\left(p^2+a^2\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\)

= \(\frac{-2 p^3-2 p a^2-4 p \dot{a}^2+4 p^3}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3}=\frac{2 \dot{p}^3-6 p a^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3}\)

28. Find \(L\left[t^2 \cos 2 t\right]\).

Solution:

We know that \(L[\cos 2 t]=\frac{p}{p^2+4}\)

Hence, \(L\left[t^2 \cos 2 t\right]=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left[\frac{p}{p^2+4}\right]=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p^2+4-2 p^2}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\right]=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{4-p^2}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+4\right)^2(-2 p)-\left(4-p^2\right) 4 p\left(p^2+4\right)}{\left(p^2+4\right)^4}=\frac{-2 p\left(p^2+4\right)-4 p\left(4-p^2\right)}{\left(p^2+4\right)^3}\)

= \(\frac{-2 p\left(p^2+4+8-2 p^2\right)}{\left(p^2+4\right)^3}=\frac{2 p\left(p^2-12\right)}{\left(p^2+4\right)^3}\)

Laplace Transform II Solved Problems In Control Systems

29. Find \(L\left\{t^2 \cos 3 t\right\}\).

Solution:

Since, \( L\{\cos 3 t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+9}=f(p)\)

∴ \(L\left\{t^2 \cos 3 t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}[f(p)]=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left[\frac{p}{p^2+9}\right]=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{9-p^2}{\left(p^2+9\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+9\right)^2(-2 p)-\left(9-p^2\right) 2\left(p^2+9\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^4} \text {, using Quotient Rule }\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+9\right)\left[-2 p\left(p^2+9\right)-4 p\left(9-p^2\right)\right]}{\left(p^2+9\right)^4}=\frac{-2 p^3-18 p-36 p+4 p^3}{\left(p^2+9\right)^3}=\frac{2 p^3-54 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^3} .\)

30. Find \(L\left\{t^2 \sin 2 t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{t^2 \sin 2 t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}[L(\sin 2 t)]=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{2}{p^2+4}\right\}\right]\)

= \(2 \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{-1}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2} 2 p\right]=(-4) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\right]=(-4) \frac{\left(p^2+4\right)^2-2 p\left(p^2+4\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+4\right)^4}\)

= \((-4) \frac{\left(p^2+4\right)\left[\left(p^2+4\right)-4 p^2\right]}{\left(p^2+4\right)^4}=(-4) \frac{4-3 p^2}{\left(p^2+4\right)^3}=\frac{4\left(3 p^2-4\right)}{\left(p^2+4\right)^3} \text {. }\)

31. Find \(L\left\{\left(t^2-3 t+2\right) \sin 3 t\right\}\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\sin 3 t\}=\frac{3}{p^2+9}=f(p)\).

Now \(L\{t \sin 3 t\}=-\frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{3}{p^2+9}\right)\)

L\(\left\{t^2 \sin 3 t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left(\frac{3}{p^2+9}\right)=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{3}{p^2+9}\right)\right]\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left[3 \frac{-2 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^2}\right]=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{-6 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(-6\left[\frac{\left(p^2+9\right)^2(1)-p(4 p)\left(p^2+9\right)}{\left(p^2+9^2\right)^4}\right]=-6\left[\frac{\left(p^2+9\right)-4 p^2}{\left(p^2+9\right)^3}\right]=\frac{6\left(3 p^2-9\right)}{\left(p^2+9\right)^3}\)

∴ L \(\left\{\left(t^2-3 t+2\right) \sin 3 t\right\}=\frac{6\left(3 p^2-9\right)}{\left(p^2+9\right)^3}-\frac{18 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^2}+\frac{6}{p^2+9}=\frac{6 p^4-18 p^3+126 p^2-162 p+432}{\left(p^2+9\right)^3}\)

Complex Laplace Transform II Problems With Solutions

32. Find \(L\left(t^2 \sin a t\right)\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{t^2 \sin a t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}[L\{\sin a t\}]=\frac{d}{d p} \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{a}{p^2+a^2}\right\}=a \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{-2 p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\right\}\)

= \(-2 a\left[\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2-2 p\left(p^2+a^2\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\right]=-2 a\left[\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right)\left(p^2+a^2-4 p^2\right)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\right]\)

= \(-2 a\left[\frac{a^2-3 p^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3}\right]=\frac{2 a\left(3 p^2-a^2\right)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3}\)

33. Find the Laplace transform of \(t^3 \cos a t\).

Solution:

L\(\{\cos a t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\)

L\(\left\{t^3 \cos a t\right\}=(-1)^3 \frac{d^3}{d p^3}\left(\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\right)=-\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left(\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\right)=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left(\frac{p^2-a^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2}\right)\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2(2 p)-\left(p^2-a^2\right) 2\left(p^2+a^2\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\right)=\frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{2 p^3+2 p a^2-4 p^3+4 p a^2}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3}\right)\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{6 p a^2-2 p^3}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3}\right)=\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^3\left(6 a^2-6 p^2\right)-\left(6 p a^2-2 p^3\right) 3\left(p^2+a^2\right)^2 2 p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^6}\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+a^2\right)\left(6 a^2-6 p^2\right)-6 p\left(6 p a^2-2 p^3\right)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}=\frac{6 p^2 a^2-6 p^4+6 a^4-6 p^2 a^2-36 p^2 a^2+12 p^4}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\)

= \(\frac{6 p^4-36 p^2 a^2+6 a^4}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}=\frac{6\left(p^4-6 p^2 a^2+a^4\right)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\)

Second method: We know that \(L\left(t^3\right)=\frac{3!}{p^4}=\frac{6}{p^4}\).

L\(\left(t^3 \cos a t\right)=\text { R. P. } L\left(t^3 e^{a i i}\right)=\text { R. P. } \frac{6}{(p+a i)^4}=\text { R.P. } \frac{6(p-a i)^4}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}=\frac{6\left(p^4-6 p^2 a^2+a^4\right)}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^4}\)

34. Find \(L\left(t^3 \cos t\right)\).

Solution:

L\(\{t \cos t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

L\(\left\{t^3 \cos t\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^3}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right\}=-\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{\left(p^2+1\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}\)

= \(-\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{p^2-1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}=\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^2 \cdot 2 p-\left(p^2-1\right) 2\left(p^2+1\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\right\}\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{2 p^3+2 p-4 p^3+4 p}{(p+1)^3}\right\}=\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{6 p-2 p^3}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3}\right\}=\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^3\left(6-6 p^2\right)-\left(6 p-2 p^3\right) 3\left(p^2+1\right)^2(2 p)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^6}\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)\left(6-6 p^2\right)-6 p\left(6 p-2 p^3\right)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}=\frac{6 p^2+6-6 p^4-6 p^2-36 p^2+12 p^4}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\)

= \(\frac{6 p^4-30 p^2+6}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}=\frac{6\left(p^4-5 p^2+1\right)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\)

35. Find the Laplace transform of \(\left(1+t e^{-t}\right)^2\).

Solution:We have to \(\left(1+t e^{-t}\right)^2=1+2 t e^{-t}+t^2 e^{-2 t}\)

∴ \(L\left\{\left(1+t e^{-t}\right)^2\right\}=L(1)+2 L\left\{t e^{-t}\right\}+L\left\{t^2 e^{-2 t}\right\}\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}+2(-1)+(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{1}{p+1}\right)+(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left(\frac{1}{p+2}\right)=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{2}{(p+1)^2}+\frac{2}{(p+2)^3}\)

36. Find the Laplace transform of \(t^2 e^{-2 t}\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{e^{-2 t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p+2} \Rightarrow L\left\{t^2 e^{-2 t}\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left(\frac{1}{p+2}\right)=\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{-1}{(p+2)^2}\right]=\frac{2}{(p+2)^3}\)

37. If \(L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\) then find \(L\left\{t^{-1 / 2}\right\}\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 p^{3 / 2}}\)Let \(F(t)=t^{-1 / 2} \text { and } L[F(t)]=f(p) \text {. }\)

We have \(\left.L\{t F(t)\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)] \Rightarrow L \mid t \cdot t^{-1 / 2}\right\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]\)

⇒ \(L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)] \Rightarrow \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=-L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}=-\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2 t^{3 / 2}}\)

⇒ \(L\left\{t^{-1 / 2}\right\}=f(p)=-\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\left[\frac{t^{-1 / 2}}{-1 / 2}\right]=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{\sqrt{t}}\)

38. Find \(L\left(t e^{-t} \sin t\right)\).

Solution:

We know that \(L(\sin t)=\frac{1}{p^2+1} \Rightarrow L\left(e^{-t} \sin t\right)=\frac{1}{(p+1)^2+1}=\frac{1}{p^2+2 p+2}\)

L\(\left(t e^{-t} \sin t\right)=-\frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{1}{p^2+2 p+2}\right)=\frac{2(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+2\right)^2}\)

39. Find the Laplace transform of the function \(t e^{-t} \sin 2 t\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\sin 2 t\}=\frac{2}{p^2+2^2}=\frac{2}{p^2+4}=f(p)\)

∴ \(L\{t \sin 2 t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[f(p)]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{2}{p^2+4}\right]=(-2)\left[\frac{-1}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2} 2 p\right]=\frac{4 p}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\)

Hence by First Shifting theorem, \(L\left\{t e^{-t} \sin 2 t\right\}=\left[\frac{4 p}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\right]_{p \rightarrow p+1}=\frac{4(p+1)}{\left[(p+1)^2+4\right]^2}=\frac{4(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+5\right)^2}\)

40. Find \(L\left[e^{-t} t \sin 3 t\right]\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\sin 3 t\}=\frac{3}{p^2+9}\)

L\(L\{t \sin 3 t\}=-\frac{d}{d p}[L\{\sin 3 t\}]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{3}{p^2+9}\right]=\frac{6 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^2}\)

By first shifting theorem \(L\left\{e^{-t} t \sin 3 t\right\}=\frac{6(p+1)}{\left[(p+1)^2+9\right]^2}=\frac{6(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+10\right)^2} \text {. }\)

41. Find the Laplace transform of \(t e^{2 t} \sin 3 t\).

Solution:

Since, \( L\{\sin 3 t\}=\frac{3}{p^2+9} \text {. }\)

∴ \(L\left\{e^{2 t} \sin 3 t\right\}=\frac{3}{(p-2)^2+9}=\frac{3}{p^2-4 p+13}\)

Hence \(L\left\{t e^{2 t} \sin 3 t\right\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{3}{p^2-4 p+13}\right)=(-3) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\left(p^2-4 p+13\right)^{-1}\right]\)

= \((-3)(-1)\left(p^2-4 p+13\right)^{-2}(2 p-4)=\frac{6(p-2)}{\left(p^2-4 p+13\right)^2}\)

42. Find \(L\left\{t e^{3 t} \sin 2 t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{\sin 2 t\}=\frac{2}{p^2+4} L\left\{e^{3 t} \sin 2 t\right\}=\left(\frac{2}{p^2+4}\right)_{p \rightarrow p-3}=\frac{2}{(p-3)^2+4}=\frac{2}{p^2-6 p+13}\)

Hence, \(L\left\{t e^{3 t} \sin 2 t\right\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{2}{p^2-6 p+13}\right)=(-2) \frac{-1}{\left(p^2-6 p+13\right)^2}(2 p-6)\)

= \(\frac{4(p-3)}{\left(p^2-6 p+13\right)^2}\)

43. Find \(L\left\{t e^{-2 t} \sin 3 t\right\}\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\sin 3 t\}=\frac{3}{p^2+9}\)

L\(\{t \sin 3 t\}=-\frac{d}{d p}[L\{\sin 3 t\}]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{3}{p^2+9}\right]=\frac{6 p}{\left(p^2+9\right)^2}\)

By first shifting theorem \(L\left\{e^{-2 t} t \sin 3 t\right\}=\frac{6(p+2)}{\left[(p+2)^2+9\right]^2}=\frac{6(p+2)}{\left(p^2+4 p+13\right)^2}\)

44. Find \(L\left[t e^{-2 t} \cdot \cos 3 t\right]\).

Solution:

We have \(L[\cos 3 t]=\frac{p}{p^2+3^2}\)

∴ \(L\left[e^{-2 t} \cos 3 t\right]=\frac{p^2+3^2}{(p+2)^2+3^2}=\frac{p+2}{p^2+4 p+13}\)

∴ \(L\left[t e^{-2 t} \cos 3 t\right]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p+2}{p^2+4 p+13}\right]=-\frac{\left(p^2+4 p+13\right) \cdot 1-(p+2)(2 p+4)}{\left(p^2+4 p+13\right)^2}\)

= \(-\frac{p^2+4 p+13-2 p^2-8 p-8}{\left(p^2+4 p+13\right)^2}=-\frac{-p^2-4 p+5}{\left(p^2+4 p+13\right)^2}=\frac{p^2+4 p-5}{\left(p^2+4 p+13\right)^2}\)

45. Find \(L\left\{t e^{2 t} \sin 3 t\right\}\).

Solution:

We have \(L(\sin 3 t)=\frac{3}{p^2+9}\)

∴ \(L\left(e^{2 t} \sin 3 t\right)=\frac{3}{(p-2)^2+9}=\frac{3}{p^2-4 p+13}\)

∴ \(L\left[t e^{2 t} \sin 3 t\right]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{3}{p^2-4 p+13}\right]=-\frac{-3(2 p-4)}{\left(p^2-4 p+13\right)^2}=\frac{6(p-2)}{\left(p^2-4 p+13\right)^2}\)

46. Find \(L\left\{t e^{a t} \sin b t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{\sin b t\}=\frac{b}{p^2+b^2} \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{a t} \sin b t\right\}=\left(\frac{b}{p^2+b^2}\right)_{p \rightarrow p-a}=\frac{b}{(p-a)^2+b^2}\)

Hence \(L\left\{t e^{a t} \sin b t\right\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{b}{(p-a)^2+b^2}\right]=(-b) \frac{-1}{\left[(p-a)^2+b^2\right]^2} 2(p-a)\)

= \(\frac{2 b(p-a)}{\left[(p-a)^2+b^2\right]^2}\)

47. Find \(L\left\{t e^{-t} \cosh t\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{\cosh t\}=\frac{p}{p^2-1} \Rightarrow L\{t \cosh t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p}{\dot{p}^2-1}\right]=(-1)\left[\frac{\left(p^2-1\right) 1-p \cdot 2 p}{\left(p^2-1\right)^2}\right]=\frac{1+p^2}{\left(p^2-1\right)^2}\)

By First Shifting theorem, \(L\left\{e^{-t} t \cosh t\right\}=\left[\frac{1+p^2}{\left(p^2-1\right)^2}\right]_{p \rightarrow p+1}=\frac{1+(p+1)^2}{\left.\left[(p+1)^2-1\right]^2\right]}=\frac{p^2+2 p+2}{\left(p^2+2 p\right)^2}\)

48. Find \(L\left[t e^{-2 t} \cosh t\right]\).

Solution:

We know that, \(L[\cosh t]=\frac{p}{p^2-1}\)

L\(\left[e^{-2 t} \cosh t\right]=\frac{p+2}{(p+2)^2-1}=\frac{p+2}{p^2+4 p+3}\)

∴ \(L\left[t e^{-2 t} \cosh t\right]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p+2}{p^2+4 p+3}\right]=(-1) \frac{\left[\left(p^2+4 p+3\right) \cdot 1-(p+2)(2 p+4)\right]}{\left(p^2+4 p+3\right)^2}\)

= \(\frac{-\left[p^2+4 p+3-\left(2 p^2+8 p+8\right)\right]}{\left(p^2+4 p-3\right)^2}=\frac{p^2+4 p+5}{\left(p^2+4 p-3\right)^2}\)

49. Find the Laplace transform of \(t^2 e^{-2 t} \cos t\).

Solution:

We know that \(L\{\cos t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

L\(\left\{t^2 \cos t\right\}=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right\}=\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{1-p^2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}\)

= \(\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^2(-2 p)-\left(1-p^2\right) 2\left(p^2+1\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}=\frac{2 p\left(p^2-3\right)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3}\)

L\(\left\{t^2 e^{-2 t} \cos t\right\}=\frac{2(p+2)\left[(p+2)^2-3\right]}{\left[(p+2)^2+1\right]^3}=\frac{2(p+2) \cdot\left(p^2+4 p+1\right)}{\left(p^2+4 p+5\right)^3}\)

50. Find the Laplace transform of \(t^3 e^{2 t} \sin t\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{t^3 e^{2 t} \sin t\right\}=\text { I.P } L\left\{t^3 e^{2 t} e^{i t}\right\}=\text { I.P } L\left\{t^3 e^{(2+i) t}\right\}\)

L\(\left\{t^3\right\}=\frac{6}{p^4} \Rightarrow L\left[t^3 e^{(2+i) t}\right]=\frac{6}{(p-2-i)^4}\)

L\(\left\{t^3 e^{2 t} \sin t\right\}=\text { I.P } \frac{6}{[(p-2)-i]^4}=\text { I.P } \frac{6[(p-2)+i]^4}{\left[(p-2)^2+1\right]^4}=\frac{6\left[4(p-2)^3-4(p-2)\right]}{\left(p^2-4 p+5\right)^4}\)

= \(\frac{24(p-2)\left(p^2-4 p+3\right)}{\left(p^2-4 p+5\right)^4}\)

51. Find \(L\left\{\int_0^t t e^{-t} \sin 4 t d t\right\}\)

Solution:

L\(\{\sin 4 t\}=\frac{4}{p^2+16} \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{-t} \sin 4 t\right\}=\left(\frac{4}{p^2+16}\right)_{p \rightarrow p+1}=\frac{4}{(p+1)^2+16}=\frac{4}{p^2+2 p+17}\)

∴ \(L\left[t e^{-t} \sin 4 t\right]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{4}{p^2+2 p+17}\right]=(-4)\left[-\frac{1}{\left(p^2+2 p+17\right)^2}(2 p+2)\right]\)

= \(\frac{8(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+17\right)^2}=f(p), \text { say }\)

\(L\left\{\int_0^t t e^{-t} \sin 4 t d t\right\}=\frac{1}{p} f(p)=\frac{1}{p} \frac{8(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+17\right)^2}=\frac{8(p+1)}{p\left(p^2+2 p+17\right)^2} \text {. }\)52. Find \(L\left[\int_0^t t e^{-t} \sin 2 t d t\right]\).

Solution:

L\(\{\sin 2 t\}=\frac{2}{p^2+4} \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{-t} \sin 2 t\right\}=\left(\frac{2}{p^2+4}\right)_{p \rightarrow p+1}=\frac{2}{(p+1)^2+4}=\frac{2}{p^2+2 p+5}\)

∴ \(L\left[t e^{-t} \sin 2 t\right]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{2}{p^2+2 p+5}\right]=(-2)\left[-\frac{1}{\left(p^2+2 p+5\right)^2}(2 p+2)\right]\)

= \(\frac{4(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+5\right)^2}=f(p), \text { say }\)

Hence, \(L\left\{\int_0^t t e^{-t} \sin 2 t d t\right\}=\frac{1}{p} f(p)=\frac{1}{p} \frac{4(p+1)}{\left(p^2+2 p+5\right)^2}=\frac{4(p+1)}{p\left(p^2+2 p+5\right)^2}\)

53. Show that \(\int_0^{\infty} t^3 e^{-t} \sin t d t=0\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t^3 e^{-t} \sin t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(t^3 \sin t\right) d t=L\left\{t^3 \sin t\right\} \text { where } p=1\)

L\(\left\{t^3 \sin t\right\}=(-1)^3 \frac{d^3}{d p^3}[L\{\sin t\}]=-\frac{d^3}{d p^3}\left\{\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right\}=-\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left[\frac{-2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right]\)

⇒ \(\left.=2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right\}=2 \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^2-p 2\left(p^2+1\right) 2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\right\}=2 \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)\left[p^2+1-4 p^2\right]}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\right\}\right\}\)

= \(2 \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{1-3 p^2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^3}\right\}=2\left[\frac{\left(p^2+1\right)^3(-6 p)-\left(1-3 p^2\right) 3\left(p^2+1\right)^2 2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^6}\right]\)

= \(2\left[\frac{-6 p^3-6 p-6 p+18 p^2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\right]=2\left[\frac{12 p^2-12 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^4}\right]\)

∴ \(\int_0^{\infty} t^3 e^{-t} \sin t d t=0\)

54. If L[F(t)]=f(p), then show that \(L\left[\frac{F(t)}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p\), provided the integral

Solution:

Given \(f(p)=L[F(t)]=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t\)

Integrating both sides w.r.t ‘ p’ from p to ∞, we get \(\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left[\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t\right]\)

The order of integration in the double integral can be interchanged since ‘ p ‘ and ‘ t ‘ are independent variables.

∴ \(\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_0^{\infty} d t \int_p^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d p=\int_0^{\infty} F(t) d t \int_p^{\infty} e^{-p t} d p=\int_0^{\infty} F(t) d t\left[\frac{e^{-p t}}{-t}\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{F(t)}{t} \cdot e^{-p t} d t=L\left[\frac{F(t)}{t}\right]\)

55. Find the Laplace transform of \(\frac{1-e^t}{t}\).

Solution:

We know that \(L\left(1-e^{\prime}\right)=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{p-1}\)

∴ \(\left.\left.L\left[\frac{1-e^t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{p-1}\right) d p=\log p-\log (p-1)\right]_p^{\infty}=\log \frac{p}{p-1}\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(0-\log \frac{p}{p-1}=\log \left(\frac{p-1}{p}\right)=\log \left(1-\frac{1}{p}\right) .\)

56. Find \(L\left\{\frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}}{t}\right\}\).

Solution:

Let \(F(t)=e^{-a t}-e^{-b t} \text {. Then } L\left\{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p+a}-\frac{1}{p+b}=f(p)\)

L\(\left\{\frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}}{t}\right\}=L\left\{\frac{F(t)}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p+a}-\frac{1}{p+b}\right) d p\)

= \(\log (p+a)-\log (p+b)]_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+a}{p+b}\right)_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+b}{p+a}\right) .\)

57. Find \(L\left\{\frac{e^{a t}-e^{-b t}}{t}\right\}\)

Solution:

Let \(F(t)=e^{a t}-e^{-b t} \text { : Then } L\left\{e^{a t}-e^{-b t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p-a}-\frac{1}{p+b}=f(p)\)

L\(\left\{\frac{e^{a t}-e^{-b t}}{t}\right\}=L\left\{\frac{F(t)}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p-a}-\frac{1}{p+b}\right) d p\)

= \(\log (p-a)-\log (p+b)]_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p-a}{p+b}\right)_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+b}{p-a}\right) .\)

58. Evaluate \(L\left[\frac{\sin t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\left[\frac{\sin t}{t}\right]\).

L\((\sin t)=\frac{1}{p^2+1} \Rightarrow L\left\{\frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{1}{p^2+1} d p=\ Tan^{-1} p_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1} p=\ Cot^{-1} p=\ Tan^{-1} \frac{1}{p}\)

59. Evaluate \(L\left[\frac{\sin a t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\left[\frac{\sin a t}{t}\right]\)We know that \(L(\sin a t)=\frac{a}{p^2+a^2}\)

∴ \(L\left(\frac{\sin a t}{t}\right)=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{a}{p^2+a^2} \dot{d p}=\left[\text{Tan}^{-1} \frac{p}{a}\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\text{Tan}^{-1} \frac{p}{a}=\text{Cot}^{-1} \frac{p}{a}\)

60. Show that \(L\left\{\frac{\cos a t}{t}\right\}\) does not exist.

Solution:

L\(\{\cos a t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}=f(p)\)

L\(\left\{\frac{\cos a t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{p}{p^2+a^2} d x=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+a^2\right)_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \infty-\log \left(p^2+a^2\right)\right] \text {, does not exist. }\)

61. Find \(L\left\{\frac{\sinh a t}{t}\right\}\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\sinh (a t)\}=\frac{a}{p^2-a^2}=f(p)\)

L\(\left\{\frac{\sinh a t}{t}\right\}=\int_n^{\infty} \frac{a}{p^2-a^2} d p=a \frac{1}{2 a} \log \left|\frac{p-a}{p+a}\right|_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2} \log \left|\frac{1-a / p}{1+a / p}\right|_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1-10}{1+0}\right)-\log \left(\frac{1-a / p}{1+a / p}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left[-\log \left(\frac{p-a}{p+a}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p+a}{p-a}\right)\)

62. Show that \(L\left\{\frac{\cosh (a t)}{t}\right\}\) does not exist.

Solution:

We have \(L\{\cosh (a t)\}=\frac{p}{p^2-a^2}=f(p)\)

L\(\left\{\frac{\cosh a t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{p}{p^2-a^2} d p=\frac{1}{2} \log \left|p^2-a^2\right|_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log (\infty)-\log \left(p^2-a^2\right)\right] .\)

This does not exist.

63. Find the Laplace transform of \(\frac{1-\cos t}{t}\).

Solution:

We know that \(L[1-\cos t]=L(1)-L[\cos t]=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

∴ \(\left.\left.L\left[\frac{1-\cos t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right) d p=\log p-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+1\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\log \frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(0-\log \frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+1}{p^2}\right)\)

64. Evaluate \(L\left\{\frac{1-\cos a t}{t}\right\}\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\left\{\frac{1-\cos a t}{t}\right\}\)Since \(L\{1-\cos a t\}=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{1-\cos a t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}\right) d p=\left[\log p-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+a^2\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[2 \log p-\log \left(p^2+a^2\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{p^2}{p^2+a^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log 1-\log \frac{p^2}{p^2+a^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1}{1+\frac{a^2}{p^2}}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2}{p^2+a^2}\right)=\log \left(\frac{p^2}{p^2+a^2}\right)^{-1 / 2}=\log \frac{\sqrt{p^2+a^2}}{p^2} .\)

65. Find the Laplace transform of \(\left[\frac{\cos t-\cos 2 t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

We know that \(L[\cos t-\cos 2 t]=\frac{p}{p^2+1}-\frac{p}{p^2+4}\)

L\(L\left[\frac{\cos t-\cos 2 t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{p}{p^2+1}-\frac{p}{p^2+4}\right) d p=\left[\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+1\right)-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+4\right)\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \frac{\left(1+1 / p^2\right)}{\left(1+4 / p^2\right)}\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log 1-\log \left(\frac{p^2+1}{p^2+4}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left(-\log \frac{p^2+1}{p^2+4}\right)=\frac{1}{2} \log \frac{p^2+4}{p^2+1}\)

66. Find \(L\left\{\frac{\cos 2 t-\cos 3 t}{t}\right\}\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\cos 2 t-\cos 3 t\}=L\{\cos 2 t\}-L\{\cos 3 t\}\) \(=\frac{p}{p^2+4}-\frac{p}{p^2+9}=f(p), \text { say }\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{\cos 2 t-\cos 3 t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{p}{p^2+4}-\frac{p}{p^{2+9}}\right) d p=\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{2 p}{p^2+4}-\frac{2 p}{p^2+9}\right) d p\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(p^2+4\right)-\log \left(p^2+9\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{p^2+4}{p^2+9}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1+4 / p^2}{1+9 / p^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1+0}{1+0}\right)-\log \left(\frac{1+4 / p^2}{1+9 / p^2}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left[0-\log \left(\frac{p^2+4}{p^2+9}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+9}{p^2+4}\right)\)

= \(\log \left(\frac{p^2+9}{p^2+4}\right)^{1 / 2} L\{\sin 3 t \cos t\}=L\left\{\frac{\sin 4 t+\sin 2 t}{2}\right\}=\frac{1}{2} \frac{1}{p^2+16}+\frac{1}{2} \frac{2}{p^2+4}\)

= \(\frac{2}{p^2+16}+\frac{1}{p^2+4}\)

67. Find the Laplace transform of \(\left[\frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

We have \(L\{\cos a t-\cos b t\}=L\{\cos a t\}-L\{\cos b t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{p}{p^2+b^2}=f(p)\), say

L\(\left\{\frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{p}{p^2+b^2}\right) d p=\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{2 p}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{2 p}{p^2+b^2}\right) d p\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(p^2+a^2\right)-\log \left(p^2+b^2\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{p^2+a^2}{p^2+b^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1+a^2 / p^2}{1+b^2 / p^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1+0}{1+0}\right)-\log \left(\frac{1+a^2 / p^2}{1+b^2 / p^2}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left[0-\log \left(\frac{p^2+a^2}{p^2+b^2}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+b^2}{p^2+a^2}\right)\)

68. Find \(L\left\{\frac{\sin 3 t \cos t}{t}\right\}\)

Solution:

⇒ \(\left.L\left\{\frac{\sin 3 t \cos t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty}\left[\frac{2}{p^2+16}+\frac{1}{p^2+4}\right] d p=(2) \frac{1}{4} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{4}+\frac{1}{2} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{2}\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)-\frac{1}{2} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{4}+\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right)-\frac{1}{2} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{2}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{1}{2} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{4}-\frac{1}{2} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{2} .\)

69. Find \(L\left[\frac{\cos 4 t \sin 2 t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

L\(\{\cos 4 t \sin 2 t\}=\frac{1}{2} L\{2 \cos 4 t \sin 2 t\}=\frac{1}{2} L\{\sin 6 t-\sin 2 t\}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\frac{6}{p^2+6^2}-\frac{2}{p^2+2^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{3}{p^2+6^2}-\frac{1}{p^2+2^2}=f(p)\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{\cos 4 t \sin 2 t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{3}{p^2+6^2}-\frac{1}{p^2+2^2}\right) d p\)

= \(\left[3 \frac{1}{6} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{6}-\frac{1}{2} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{2}\right]_0^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\frac{\pi}{2}\right)-\frac{1}{2}\left(\ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{6}-\ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{2}\right)\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left(\ Tan^{-1} \cdot \frac{p}{2}-\ Tan^{-1} \frac{p}{6}\right) .\)

70. Solve \(L\left\{\frac{e^t-\cos t}{t}\right\}\).

Solution:L\(\left\{e^t-\cos t\right\}=L\left\{e^t\right\}-L\{\cos t\}=\frac{1}{p-1}-\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

L\(\left\{\frac{e^t-\cos t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty}\left[\frac{1}{p-1}-\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right] d p=\left[\log (p-1)-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+1\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\left[\log \left(\frac{p-1}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=0-\log \left(\frac{p-1}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}\right)=\frac{1}{2} \log \left[\frac{p^2+1}{(p-1)^2}\right]\)

71. Find \(L\left[\frac{e^{-2 t} \sin 2 t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

L\([\sin 2 t]=\frac{2}{s^2+2^2} \Rightarrow L\left[e^{-2 t} \sin 2 t\right]=\frac{2}{(s+2)^2+2^2}\)

∴ \(\left.L\left[\frac{e^{-2 t} \sin 2 t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{2}{(p+2)^2+2^2} d s=\ Tan^{-1} \frac{p+2}{2}\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1} \frac{p+2}{2}=\ Cot^{-1}\left(\frac{p+2}{2}\right)\)

72. Find \(L\left[\frac{e^{-3 t} \sin 2 t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

L\(\{\sin 2 t\}=\frac{2}{p^2+2^2} \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{-3 t} \sin 2 t\right\}=\left(\frac{2}{p^2+2^2}\right)_{p \rightarrow p+3}=\frac{2}{(p+3)^2+2^2}=f(p), \text { say }\)

∴\(L\left[\frac{e^{-3 t} \sin 2 t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{2}{(p+3)^2+2^2} d p=2 \frac{1}{2}\left[\ Tan^{-1}\left(\frac{p+3}{2}\right)_p^{\infty}\right.\)

= \(\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1}\left(\frac{p+3}{2}\right)=\ Cot^{-1}\left(\frac{p+3}{2}\right)\)

73. Evaluate \(L\left[e^{-4 t} \frac{\sin 3 t}{t}\right]\).

Solution:

Given

\(L\left[e^{-4 t} \frac{\sin 3 t}{t}\right]\)L\(\{\sin 3 t\}=\frac{3}{p^2+3^2} \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{-4 t} \sin 3 t\right\}=\left(\frac{3}{p^2+3^2}\right)_{p \rightarrow p+4}=\frac{3}{(p+4)^2+3^2}=f(p) \text {, say }\)

∴ \(L\left[\frac{e^{-4 t} \sin 3 t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{3}{(p+4)^2+3^2} d p=3 \frac{1}{3}\left[\ Tan^{-1}\left(\frac{p+4}{3}\right)_p^{\infty}\right.\)

= \(\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1}\left(\frac{p+4}{3}\right)=\ Cot^{-1}\left(\frac{p+4}{3}\right)\)

74. Find \(L\left\{\frac{1-\cos t}{t^2}\right\}\).

Solution:

We know that \(L[1-\cos t]=L(1)-L[\cos t]=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+1}\)

∴ L\(\left[\frac{1-\cos t}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right) d p=\log p-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+1\right)_p^{\infty}=\log \frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}_p^{\infty}\)

= \(0-\log \frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+1}{p^2}\right)\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{1-\cos t}{t^2}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+1}{p^2}\right) d p=\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left[\log \left(p^2+1\right)-\log p^2\right] d p\)

= \(\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left[\log \left(p^2+1\right)-2 \log p\right] 1 d p\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\left\{\log \left(p^2+1\right)-2 \log p\right\}_p\right]_p^{\infty}-\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{2 p}{p^2+1}-\frac{2}{p}\right) p d p\)

= \(\left[\frac{p}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+1}{p^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}+\int_p^{\infty} \frac{1}{p^2+1} d p=\left[\frac{p}{2} \log \left(1+\frac{1}{p^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}+\left(\text{Tan}^{-1} p\right)_p^{\infty}\)

= \(-\frac{p}{2} \log \left(1+\frac{1}{p^2}\right)+\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\text{Tan}^{-1} p\right)=\text{Cot}^{-1} p-\frac{p}{2} \log \left(1+\frac{1}{p^2}\right)\)

75. Find the Laplace transform of \(\int_0^t \frac{\sin t}{t} d t\).

Solution:

L\((\sin t)=\frac{1}{p^2+1}\)

∴ \(\left.\Rightarrow L\left\{\frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{1}{p^2+1} d p=\ Tan^{-1} p\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1} p=\ Cot^{-1} p=\ Tan^{-1} \frac{1}{p} .\)

L\(\left\{\int_0^t \frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p} L\left\{\frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p} \ Tan^{-1} \frac{1}{p}\)

76. Find \(L\left[\int_0^t \frac{1-e^{-t}}{t} d t\right]\).

Solution:

Let \(F(t)=1-e^{-t} \text {. Then } f(p)=L\left\{1-e^{-t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{p+1}\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{1-e^{-t}}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{p+1}\right) d p=[\log p=\log (p+1)]_p^{\infty}=\left[\log \left(\frac{p}{p+1}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\left[\log \left(\frac{1}{1+1 / p}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{1}{1+0}\right)-\log \left(\frac{1}{1+1 / p}\right)=0-\log \left(\frac{p}{p+1}\right)=\log \left(\frac{p+1}{p}\right)=f(p)\)

⇒ \(L\left[\int_0^t \frac{1-e^{-t}}{t} d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} f(p)=\frac{1}{p} \log \left(\frac{p+1}{p}\right)=\frac{1}{p} \log \left(1+\frac{1}{p}\right)\)

77. Find \(L\left\{\int_0^t \frac{e^t \sin t}{t} d t\right\}\)

Solution:

We know that \(L\{\sin t\}=\frac{1}{p^2+1}\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{1}{p^2+1} d p=\left(\tan ^{-1} p\right)_p^{\infty}=\tan ^{-1} \infty-\tan ^{-1} p=\frac{\pi}{2}-\tan ^{-1} p=\cot ^{-1} p\)

By First Shifting theorem, \(L\left\{e^t \frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\left(\cot ^{-1} p\right)_{p \rightarrow p-1}=\cot ^{-1}(p-1)=f(p)\)

Using the theorem of L.T. of the integral. \(L\left\{\int_0^t \frac{e^t \sin t}{t} d t\right\}=\frac{1}{p} f(p)=\frac{1}{p} \cot ^{-1}(p-1)\).

78. Find \(L\left[e^{-3 t} \int_0^t \frac{\sin t}{t} d t\right]\).

Solution:

Since \(L\{\sin t\}=\frac{1}{p^2+1}=f(p)\)

∴ \(L\left\{\frac{\sin t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{1}{p^2+1} d p=\left[\ Tan^{-1} p\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1} p=\text{Cot}^{-1} p\)

Hence \(L\left[\int_0^t \frac{\sin t}{t} d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} \ Cot^{-1} p\) By First Shifting theorem,

L\(\left[e^{-3 t} \int_0^t \frac{\sin t}{t} d t\right]=\left(\frac{1}{p} \ Cot^{-1} p\right)_{p \rightarrow p+3}=\frac{1}{p+3} \ Cot^{-1}(p+3)\)

79. Find the Laplace transform of \(\int_0^t e^{-t} \cosh t d t\).

Solution:

We know that \(L\{\cosh t\}=\frac{p}{p^2-1} \cdot \Rightarrow\left\{e^{-t} \cosh t\right\}=\frac{p+1}{(p+1)^2-1}=\frac{p+1}{p^2+2 p} \text {. }\)

∴ \(L\left[\int_0^t e^{-t} \cosh t d t\right]=\frac{1}{p} L\left(e^{-t} \cosh t\right)=\frac{1}{p} \frac{p+1}{p^2+2 p}=\frac{p+1}{p^2(p+2)}\)

80. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} d t\)

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} d t\)⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} d t=\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-p t} d t \text { where } p=3 . \text { But } \int_0^{\infty} t e^{-p t} d t=L\{t\}=\frac{1}{p^2}\)

Putting p=3 , we get \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} d t=\frac{1}{3^2}=\frac{1}{9} \text {. }\)

81. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-4 t} \sin 3 t d t .\)

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-4 t} \sin 3 t d t .\)⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-4 t} \sin 3 t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \sin 3 t d t=L\{\sin 3 t\} \text { where } p=4\)

But \(L\{\sin 3 t\}=\frac{3}{p^2+9} \Rightarrow \int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \sin 3 t d t=\frac{3}{p^2+9}\)

Putting p=4, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-4 t} \sin 3 t d t=\frac{3}{16+9}=\frac{3}{25} \text {. }\)

82. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-t} \sin t d t\).

Solution:

Given

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-t} \sin t d t=\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-p t} \sin t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}(t \sin t) d t=L\{t \sin t\} \text {, where } p=1 \text {. }\)

But \(L\{t \sin t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}[L(\sin t)]=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right)=(-1) \frac{-1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2} 2 p=\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\)

Putting p=1, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-t} \sin t d t=\frac{2}{(1+1)^2}=\frac{1}{2}\).

83. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-2 t} \sin t d t\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-2 t} \sin t d t\)⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-2 t} \sin t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \sin t d t \text { where } p=2\)

But \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \sin t d t=L\{t \sin t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right)=\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \sin t d t=\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2} \text {. Taking } p=2 \text {, we get } \int_0^{\infty} t e^{-2 t} \sin t d t=\frac{4}{25}\)

84. Prove that \(\int_0^1 t e^{-2 t} \cos t d t=\frac{3}{25} .\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-2 t} \cos t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}(t \cos t) d t \text { where } p=2\)

= \(L\{t \cos t\}=(-1)^1 \frac{d}{d p}[L\{\cos t\}]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{p}{p^2+1}\right\}=-\left[\frac{\left(p^2+1\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right]\)

= \(-\frac{1-p^2}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}=\frac{p^2-1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}=\frac{3}{25}\)

85. Show that \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} \sin t d t=\frac{3}{50} .\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} \sin t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \sin t d t \text { where } p=3 .\)

But \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \sin t d t=L\{t \sin t\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right)=\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \sin t d t=\frac{2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2} \text {. Taking } p=3 \text {, we get } \int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} \sin t d t=\frac{6}{100}=\frac{3}{50}\)

86. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} \cos 4 t d t\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} \cos 4 t d t\).

We know that \(L[\cos 4 t]=\frac{p}{p^2+16}\)

L\([t \cos 4 t]=-\frac{d}{d p} L[\cos 4 t]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p}{p^2+16}\right]=-\left[\frac{\left(p^2+16\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+16\right)^2}\right]=\frac{p^2-16}{\left(p^2+16\right)^2}\)

∴ \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-3 t} \cos 4 t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \cos 4 t d t=\int_0^{-p t} e^{-p}(t \cos 4 t) d t=L[t \cos 4 t] \text { where } p=3\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-3 t} t \cos 4 t=\frac{9-16}{(9+16)^2}=-\frac{7}{625}\)

87. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-4 t} \cos 2 t d t\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-4 t} \cos 2 t d t\)We know that \(L_s[\cos 2 t]=\frac{p}{p^2+4}\)

∴ \(L[t \cos 2 t]=-\frac{d}{d p} L[\cos 2 t]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{p}{p^2+4}\right]=-\left[\frac{\left(p^2+4\right) 1-p(2 p)}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\right]=\frac{p^2-4}{\left(p^2+4\right)^2}\)

Now \(\int_0^{\infty} t e^{-4 t} \cos 2 t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t \cos 2 t d t=\int_0 e^{-p t}(t \cos 2 t) d t \doteq \ L[t \cos 2 t] \text { where } p=4\)

∴ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-4 t} t \cos 2 t=\frac{16-4}{(16+4)^2}=\frac{12}{400}=\frac{3}{100} .\)

88. Show that \(\int_0^{\infty} t^3 e^{-t} \sin t d t=0\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} t^3 e^{-t} \sin t d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t^3 \sin t d t\), where p=1

But \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t^3 \sin t d t=L\left\{t^3 \sin t\right\}\)

Now \(L\left\{t^3 \sin t\right\}=(-1)^3 \frac{d^3}{d s^3}[L\{\sin t\}]=(-1) \frac{d^3}{d p^3}\left(\frac{1}{p^2+1}\right)\)

= \((-1) \frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left(\frac{-2 p}{\left(p^2+1\right)^2}\right)=2 \frac{d}{d p}\left(\frac{1-3 p^2}{\left(1+p^2\right)^3}\right)=\frac{-24 p\left(1-p^2\right)}{\left(1+p^2\right)^4}\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} t^3 \sin t d t=\frac{-24 p\left(1-p^2\right)}{\left(1+p^2\right)^4}\)

Putting p=1, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-t} t^3 \sin t d t=\frac{24(1-1)}{(1+1)^4}=0\)

89. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin t}{t} d t\)

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin t}{t} d t\)⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin t}{t} d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \frac{\sin t}{t} d t=L\left[\frac{\sin t}{t}\right] \text { where } p=0\)

L\((\sin t)=\frac{1}{p^2+1}=f(p) \Rightarrow L\left(\frac{\sin t}{t}\right)=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{d p}{p^2+1}\)

= \(\left[\ Tan^{-1} p\right]_s^{\infty}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\ Tan^{-1} p\)

Taking p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin t}{t} d t=\frac{\pi}{2} \text {. }\)

90. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin 2 t}{t} d t\).

Solution:

Given integral is the Laplace transform of \(\frac{\sin 2 t}{t} \text {. with } p=0\)

∴ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \frac{\sin 2 t}{t} d t=L\left\{\frac{\sin 2 t}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} L\{\sin 2 t\} d p=\int_p^{\infty} \frac{2}{p^2+4} d p\)

= \(2 \frac{1}{2}\left(\tan ^{-1} \frac{p}{2}\right)_p^{\infty}=\frac{\pi}{2}-\tan ^{-1} \frac{p}{2}\)

Putting p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin 2 t}{t} d t=\frac{\pi}{2} \text {. }\)

91. Using Laplace transforms show that \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin ^2 t}{t^2 \cdot} d t=\frac{\pi}{2}\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\sin ^2 t}{t^2} d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \frac{\sin ^2 t}{t^2} d t \text { where } p=0\)

= \(L\left\{\frac{\sin ^2 t}{t^2}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} L\left\{\frac{\sin ^2 t}{t}\right\} d p=\frac{1}{2} \int_0^{\infty} L\left\{\frac{1-\cos 2 t}{t}\right\} d p\)

92. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}}{t} d t\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}}{t} d t\)Let \(F(t)=e^{-a t}-e^{-b t} \text {. Then } L\left\{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p+a}-\frac{1}{p+b}=f(p)\)

L \(\left\{\frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}}{t}\right\}=L\left\{\frac{F(t)}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p+a}-\frac{1}{p+b}\right) d p\)

= \(\log (p+a)-\log (p+b)]_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+a}{p+b}\right)_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+b}{p+a}\right) .\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(\frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b}}{t}\right) d t=\log \left(\frac{p+b}{p+a}\right)\)

p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-a t}-e^{-b t}}{t} d t=\log \left(\frac{b}{a}\right)\)

93. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t}-e^{-3 t}}{t} d t\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t}-e^{-3 t}}{t} d t\)Let \(F(t)=e^{-t}-e^{-3 t} \text {. }\)

Now, \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t}-e^{-3 t}}{t} d t=\int_0^{\infty} \frac{F(t)}{t} d t==\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \frac{F(t)}{t} d t=L\left[\frac{F(t)}{t}\right] \text { where } p=0\)

Then \(L[F(t)]=L\left[e^{-t}-e^{-3 t}\right]=\frac{1}{p+1}-\frac{1}{p+3}=f(p) \text {. }\)

∴ \(L\left[\frac{F(t)}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p+1}-\frac{1}{p+3}\right) d p=[\log (p+1)-\log (p+3)]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\left[\log \left(\frac{1+1 / p}{1+3 / p}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\log 1-\log \left(\frac{p+1}{p+3}\right)=0-\log \frac{p+1}{p+3}=\log \left(\frac{p+3}{p+1}\right)\)

Taking p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty}\left(\frac{e^{-t}-e^{-3}}{t}\right) d t=\log \frac{3}{1}=\log 3 \text {. }\)

94. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t}}{t} d t=\log 2\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t}}{t} d t=\log 2\)Let \(F(t)=e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t} \text {. Then } L\left\{e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p+3}-\frac{1}{p+6}=f(p)\)

L\(\left\{\frac{e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t}}{t}\right\}=L\left\{\frac{F(t)}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p) d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p+3}-\frac{1}{p+6}\right) d p\)

= \(=\log (p+3)-\log (p+6)]_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+3}{p+6}\right)_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+6}{p+3}\right)\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(\frac{e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t}}{t}\right) d t=\log \left(\frac{p+6}{p+3}\right)\)

Putting p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-3 t}-e^{-6 t}}{t} d t=\log \left(\frac{6}{3}\right)=\log 2 \text {. }\)

95. Evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t}-e^{-2 t}}{t} d t\).

Solution:

Given

\(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t}-e^{-2 t}}{t} d t\)Let \(F(t)=e^{-t}-e^{-2 t} \text {. Then } L\left\{e^{-t}-e^{-2 t}\right\}=\frac{1}{p+1}-\frac{1}{p+2}=f(p)\)

⇒ \(L\left\{\frac{e^{-t}-e^{-2 t}}{t}\right\}=L\left\{\frac{F(t)}{t}\right\}=\int_p^{\infty} f(p))^{\infty} d p=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p+1}-\frac{1}{p+2}\right) d p\)

= \(\log (p+1)-\log (p+2)]_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+1}{p+2}\right)_p^{\infty}=\log \left(\frac{p+2}{p+1}\right)\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(\frac{e^{-t}-e^{-2 t}}{t}\right) d t=\log \left(\frac{p+2}{p+1}\right)\)

Putting p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t}-e^{-2 t}}{t} d t=\log \left(\frac{2}{1}\right)=\log 2 \text {. }\)

96. Using Laplace transform, evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t} d t\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t} d t=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(\frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t}\right) d t=L\left\{\frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t}\right\} \text { where } p=0\)

We know that \(L\{\cos a t-\cos b t\}=\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{p}{p^2+b^2}\)

∴ \(L\left[\frac{\cos a t-\cos b t^2}{t}\right]=\int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{p}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{p}{p^2+b^2}\right) d p=\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{2 p}{p^2+a^2}-\frac{2 p}{p^2+b^2}\right) d p\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(p^2+a^2\right)-\log \left(p^2+b^2\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{p^2+a^2}{p^2+b^2}\right)\right]_p^{-\infty}=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log \left(\frac{1+a^2 / p^2}{1+b^2 / p^2}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{2}\left[\log 1-\log \left(\frac{1+a^2 / p^2}{1+b^2 / p^2}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2}\left[0-\log \left(\frac{p^2+a^2}{p^2+b^2}\right)\right]=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+b^2}{p^2+a^2}\right)\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left(\frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t}\right) d t=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{p^2+b^2}{p^2+a^2}\right) .\)

Take p=0 Then \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\cos a t-\cos b t}{t} d t=\frac{1}{2} \log \left(\frac{b}{2}\right)^2=\log \left(\frac{b}{a}\right)\)

97. Using Laplace transform, evaluate \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-a t} \sin ^2 t}{t} d t\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-a t} \sin ^2 t}{t} d t=L\left[\frac{\sin ^2 t}{t}\right], \text { where } p=a\)

Now, \(L\left\{\frac{\sin ^2 t}{t}\right\}=L\left\{\frac{1-\cos 2 t}{2 t}\right\}=\frac{1}{2} L\left\{\frac{1-\cos 2 t}{t}\right\}=\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty} L\{1-\cos 2 t\} d p\)

= \(\frac{1}{2} \int_p^{\infty}\left(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{p}{p^2+4}\right) d p=\frac{1}{2}\left[\log p-\frac{1}{2} \log \left(p^2+4\right)\right]_p^{\infty}\)

= \(\frac{1}{4}\left[\log \left(\frac{p^2}{p^2+4}\right)\right]_p^{\infty}=\frac{1}{4}\left[\log \left(\frac{p^2+4}{p^2}\right)\right]\)

⇒ \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} \frac{\sin ^2 t}{t} d t=\frac{1}{4} \log \left(\frac{p^2+4}{p^2}\right)\)

Putting p=a, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-a t} \sin ^2 t}{t} d t=\frac{1}{4} \log \left(\frac{a^4+4}{a^2}\right)\)

98. Define error function.

Solution:

The error function is denoted by erf(t) and is defined } erf(t) = \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^t e^{-x^2} d x\)

99. Prove that \(L[\ erf(\sqrt{t})]=\frac{1}{p \sqrt{p+1}}\) and hence deduce that

1) \(L\{\ erf(2 \sqrt{t})\}=\frac{2}{p \sqrt{p+4}}\)

2) \(L[t \ erf(2 \sqrt{t})]=\frac{3 p+8}{p^2(p+4)^{3 / 2}}\)

Solution:

⇒ \(\ erf(\sqrt{t})=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^{\sqrt{t}} e^{-x^2} d x=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^{\sqrt{t}}\left(1-x^2+\frac{x^4}{2 !}-\frac{x^6}{3 !}+\ldots\right) d x\)

= \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[x-\frac{x^3}{3}+\frac{x^5}{5 \cdot 2 !}-\frac{u^7}{7 \cdot 3 !}+\ldots\right]_0^{\sqrt{t}}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[t^{1 / 2}-\frac{t^{3 / 2}}{3}+\frac{t^{5 / 2}}{5 \cdot 2 !}-\frac{t^{7 / 2}}{7 \cdot 3 !}+\ldots\right]\)

∴ \(L\{\ erf(\sqrt{t})\}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}-\frac{1}{3} L\left\{t^{3 / 2}\right\}+\frac{1}{5 \cdot 2 !} L\left\{t^{5 / 2}\right\}-\frac{1}{7 \cdot 3 !} L\left\{t^{7 / 2}\right\}+\ldots\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)}{p^{3 / 2}}-\frac{1}{3} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{5}{2}\right)}{p^{5 / 2}}+\frac{1}{5 \cdot 2 !} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{7}{2}\right)}{p^{7 / 2}}-\frac{1}{7 \cdot 3 !} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{9}{2}\right)}{p^{9 / 2}}+\ldots\right]\)

= \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}[\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}-\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{5 / 2}}+\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{7 / 2}}\)

–\(\frac{\pi}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{5}{6} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{9 / 2}}+\ldots\)

= \(\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\left[1-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{p}+\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{p^2}-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{5}{6} \cdot \frac{1}{p^3}+\ldots\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\left(\mathfrak{1}+\frac{1}{p}\right)^{-1 / 2}=\frac{1}{p \sqrt{p+1}}\)

Thus \(L\ erf(\sqrt{t})\}=\frac{1}{p \sqrt{p+1}} \text {. }\)

By change of scale property,

L\([\text{erf}(2 \sqrt{t})]=L[\text{erf}(\sqrt{4 t})]=\frac{1}{4} \frac{1}{(p / 4) \sqrt{p / 4+1}}=\frac{2}{p \sqrt{p+4}}\)

∴ \(L[\ t erf(2 \sqrt{t})]=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{2}{p \sqrt{p+4}}\right]=\frac{3 p+8}{p^2(p+4)^{3 / 2}}\)

100. Prove that \(L\left\{e^{3 t} \ erf(\sqrt{t})\right\}=\frac{1}{(p-3) \sqrt{p-2}}\)

Solution:

⇒ \(\ erf(\sqrt{t})=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^{\sqrt{t}} e^{-x^2} d x=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}} \int_0^{\sqrt{t}}\left(1-x^2+\frac{x^4}{2 !}-\frac{x^6}{3 !}+\ldots\right) d x\)

= \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[x-\frac{x^3}{3}+\frac{x^5}{5 \cdot 2 !}-\frac{u^7}{7 \cdot 3 !}+\ldots\right]_0^{\sqrt{t}}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[t^{1 / 2}-\frac{t^{3 / 2}}{3}+\frac{t^{5 / 2}}{5 \cdot 2 !}-\frac{t^{7 / 2}}{7 \cdot 3 !}+\ldots\right]\)

∴ \(L\{\ erf(\sqrt{t})\}=\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[L\left\{t^{1 / 2}\right\}-\frac{1}{3} L\left\{t^{3 / 2}\right\}+\frac{1}{5 \cdot 2 !} L\left\{t^{5 / 2}\right\}-\frac{1}{7 \cdot 3 !} L\left\{t^{7 / 2}\right\}+\ldots\right]\)

= \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[\frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{3}{2}\right)}{p^{3 / 2}}-\frac{1}{3} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{5}{2}\right)}{p^{5 / 2}}+\frac{1}{5 \cdot 2 !} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{7}{2}\right)}{p^{7 / 2}}-\frac{1}{7 \cdot 3 !} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{9}{2}\right)}{p^{9 / 2}}+\ldots\right]\)

= \(\frac{2}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left[\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}-\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{5 / 2}}+\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{7 / 2}}-\frac{\pi}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{5}{6} \cdot \frac{1}{p^{9 / 2}}+\ldots\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\left[1-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{1}{p}+\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{p^2}-\frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{3}{4} \cdot \frac{5}{6} \cdot \frac{1}{p^3}+\ldots\right]=\frac{1}{p^{3 / 2}}\left(1+\frac{1}{p}\right)^{-1 / 2}=\frac{1}{p \sqrt{p+1}}\)

Thus \(L\{\ erf(\sqrt{t})\}=\frac{1}{p \sqrt{p+1}}\)By first shifting theorem, \(L\left\{e^{3 t} \text{erf}(\sqrt{t})\right\}=\frac{1}{(p-3) \sqrt{(p-3)+1}}=\frac{1}{\cdot(p-3) \sqrt{p-2}} \text {. }\)

101. If \(E_i(t)=\int_0^{\infty} \frac{e^{-u}}{u}\), then evaluate \(L\left\{E_i(t)\right\}\).

Solution:

We have \(E_i(t)=\int_t^{\infty} \frac{e^{-u}}{u} d u\)

∴ \(L\left\{E_i(t)\right\}=L\left\{\int_t^{\infty} \frac{e^{-u}}{u} d u\right\}=L\left\{\int_1^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t v}}{v} d v\right\} \text {, putting } u=t v \text { so that } d u=t d v\)

= \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t}\left\{\int_1^{\infty} \frac{e^{-t v}}{v} d v\right\} d t=\int_1^{\infty} \frac{1}{v}\left\{\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} e^{-t v} d t\right\} d v \text {, changing the order of integration }\)

= \(\int_1^{\infty} \frac{1}{v}\left\{\int_0^{\infty} e^{-(p+v) t} d t\right\} d v=\int_1^{\infty} \frac{1}{v}\left[\frac{e^{-(p+v) t}}{-(p+t)}\right]_0^{\infty} d v=\int_1^{\infty} \frac{1}{v} \frac{1}{p+v} d v=\int_1^{\infty} \frac{1}{p}\left(\frac{1}{v}-\frac{1}{p+v}\right) d v\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}[\log v-\log (p+v)]=\frac{1}{p}\left[-\log \left(\frac{p}{v}+1\right)\right]_1^{\infty}=\frac{1}{p} \log (p+1) .\)

102. Define the Bessel function.

Solution:

Bessel function

The Bessel Function of order n is denoted by \(J_n(t)\) and defined as \(J_n(t)=\frac{t^n}{2^n \Gamma(n+1)}\left[1-\frac{t^2}{2(2 n+2)}+\frac{t^4}{2 \cdot 4(2 n+2)(2 n+4)}-\ldots\right]\)

= \(\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^r}{r ! \Gamma(n+r+1)}\left(\frac{t}{2}\right)^{n+2 r}\)

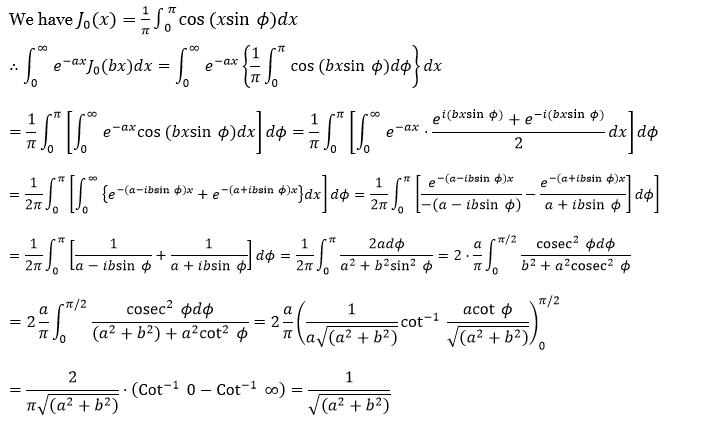

103. Prove that \(L\left[\ J_0(t)\right]=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+p^2}}\)

Solution:

⇒ \(J_n(t)=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1) r}{r ! \Gamma(r+n+1)}\left(\frac{t}{2}\right)^{n+2 r}\)

∴ \(J_0(t)=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^5}{(r !)^2}\left(\frac{t}{2}\right)^{2 r}=1-\frac{t^2}{2^2}+\frac{t^4}{2^2 4^2}-\frac{t^6}{2^2 4^2 6^2}+\ldots\)

∴ \(L\left\{J_0(t)\right\}=L\{1\}-\frac{1}{2^2} \dot{L}\left\{t^2\right\}+\frac{1}{2^2 4^2} L\left\{t^4\right\}-\frac{1}{2^2 4^2 6^2} L\left\{t^6\right\}+\ldots\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{2^2} \frac{2 !}{p^3}+\frac{1}{2^2 4^2} \frac{4 !}{p^5}-\frac{!}{2^2 4^2 6^2} \frac{6 !}{p^7}+\ldots\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}\left[1-\frac{1}{2} \frac{1}{p^2}+\frac{1 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 4}\left(\frac{1}{p^2}\right)^2-\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6}\left(\frac{1}{p^2}\right)^3+\ldots\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}\left(1+\frac{1}{p^2}\right)^{-1 / 2}=\frac{1}{p \sqrt{\left(\frac{1+p^2}{p^2}\right)}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+p^2}}\)

104. Prove that \(L\left[J_0(a t)\right]=\frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+a^2}}\)⋅

Solution:

Using change of scale of property, \(L\left\{J_0(a t)\right\}=\frac{1}{a} f\left(\frac{p}{a}\right)=\frac{1}{a} \frac{1}{\sqrt{1+p^2 / a^2}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{a^2+p^2}} \text {. }\)

105. Prove that \(L\left[t J_0(a t)\right]=\frac{p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^{3 / 2}}\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{t J_0(a t)\right\}=-\frac{d}{d p} L\left\{J_0(a t)\right\}=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[\frac{1}{\sqrt{a^2+p^2}}\right]=\frac{p}{\left(p^2+a^2\right)^{3 / 2}}\)

106. Prove that \(L\left[e^{-a t} J_0(a t)\right]=\frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+2 a p+2 a^2}}\).

Solution:

By using the First Shifting theorem, L\(\left\{e^{-a t} J_0(a t)\right\}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{(p+a)^2+a^2}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+2 a p+2 a^2}}\)

107. Prove that \(\int_0^{\infty} J_0(t) d t=1\).

Solution:

We have \(L\left\{J_0(t)\right\}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+p^2}} \Rightarrow \int_0^{\infty} J_0(t) e^{-p t} d t=\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+p^2}}\)

Putting p=0, we get \(\int_0^{\infty} J_0(t) d t=1 \text {. }\)

108. Prove that \(L\left\{J_1(t)\right\}=1-\frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}\).

Solution:

We know that \(J_0^{\prime}(t)=-J_1(t)\)

From theorem on Laplace Transform of Derivative, we have L\(\left\{F^{\prime}(t)\right\}=p L\{F(t)\}-F(0)\)

∴ \(L\left\{J_1(t)\right\}=L\left\{-J_0{ }^{\prime}(t)\right\}=-L\left\{J_0{ }^{\prime}(t)\right\}=-\left[p L\left\{J_0(t)\right\}-J_0(0)\right]\)

= \(-\left[p \frac{1}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}-1\right]=1-\frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}\)

109. Prove that \(L\left\{t J_1(t)\right\}=\frac{1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^{3 / 2}}\).

Solution:

L\(\left\{t J_1(t)\right\}=-\frac{d}{d p} L\left\{J_1(t)\right\}=-\frac{d}{d p}\left[1-\frac{p}{\sqrt{p^2+1}}\right]=\frac{1}{\left(p^2+1\right)^{3 / 2}}\)

110. Show that \(L\left\{J_0(a \sqrt{t})\right\}=\frac{1}{p} e^{-a^2 / 4 p}\)

Solution:

L\(\left\{J_0(\sqrt{t})\right\}=L\left\{1-\frac{t}{2^2}+\frac{t^2}{2^2 4^2}-\frac{t^3}{2^2 4^2 6^2}+\ldots\right\}\)

= \(L\{1\}-\frac{1}{2^2} L\{t\}+\frac{1}{2^2 4^2} L\left\{t^2\right\}-\frac{1}{2^2 4^2 6^2} L\left\{t^3\right\}+\ldots\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{4}\left(\frac{1}{p^2}\right)+\frac{1}{2^2 4^2} \frac{2 !}{p^3}-\frac{1}{2^2 4^2 6^2} \frac{3 !}{p^4}+\ldots=\frac{1}{p}-\frac{1}{4 p^2}+\frac{1}{32 p^3}-\frac{1}{384 p^4}+\ldots\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}\left[1-\frac{1}{4 p}+\frac{1}{32 p^2}-\frac{1}{384 p^3}+\ldots\right]=\frac{1}{p} e^{-1 / 4 p}\)

Using change of scale property, \(L\left\{J_0(a \sqrt{t})\right\}=\frac{1}{a^2} \times \frac{a^2}{p} e^{-a^2 / 4 p}=\frac{1}{p} e^{-a^2 / 4 p} \text {. }\)

111. Evaluate \(L\left\{t^2 u(t-2)\right\}\)

Solution:

Given

\(L\left\{t^2 u(t-2)\right\}\)The unit step function } u(t-2) is defined by u(t-2)= \(\begin{cases}0, & \text { if } t<2 \\ 1, & \text { if } t>2\end{cases}\)

∴ \(L\{u(t-2)\}=\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} u(t-2) d t=\int_0^2 e^{-p t} u(t-2) d t+\int_2^{\infty} e^{-p t} u(t-2) d t\)

= \(\int_0^2 e^{-p t} 0 d t+\int_2^{\infty} e^{-p t} 1 d t=0+\int_2^{\infty} e^{-p t} d t=\left(\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p}\right)_2^{\infty}=\frac{-1}{p}\left(0-e^{-2 p}\right)=\frac{e^{-2 p}}{p}\)

Hence, \(L\left\{t^2 u(t-2)\right\}=(-1)^2 \frac{d^2}{d p^2}[L\{u(t-2)\}]=\frac{d^2}{d p^2}\left\{\frac{e^{-2 p}}{p}\right\}\)

= \(\frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{p(-2) e^{-2 p}-e^{-2 p}}{p^2}\right\}=(-1) \frac{d}{d p}\left\{\frac{e^{-2 p}(2 p+1)}{p^2}\right\}\)

= \(\frac{(-1)}{p^4}\left[p^2\left\{(-2) e^{-2 p}(2 p+1)+2 e^{-2 p}\right\}-2 p e^{-2 p}(2 p+1)\right]\)

= \(\frac{2 e^{-2 p}}{p^4}\left[p^2(2 p+1-1)+p(2 p+1)\right]=\frac{2 e^{-2 p}}{p^4}\left[2 p^3+p(2 p+1)\right]=\frac{2 e^{-2 p}}{p^3}\left(1+2 p+2 p^2\right)\)

112. Find \(L\left\{e^{t-3} u(t-3)\right\}\).

Solution:

L\(\{u(t-3)\}=\frac{e^{-3 p}}{p} \Rightarrow L\left\{e^{t-3} u(t-3)\right\}=L\left\{e^{-3} e^t u(t-3)\right\}=e^{-3} L\left\{e^t u(t-3)\right\}\)

= \(e^{-3} \frac{e^{-3(p-1)}}{p-1}=\frac{e^{-3} e^{-3 p} e^3}{p-1}=\frac{e^{-3 p}}{p-1}\)

113. If F(t) is a periodic function with period T then show that \(L[F(t)]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-p T}} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t\).

Solution:

L[F(t)] = \(\int_0^{\infty} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t+\int_T^{2 T} e^{-p t} F(t) d t+\cdots \text { up to } \infty \rightarrow \text { (1) }\)

Put t=u+T in the second integral.

Then d t=d u; when t=T, u=0 and t=2 T, u=T.

⇒ \(\int_T^{2 T} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\int_0^T e^{-p(u+T)} F(u+T) d u\)

= \(\int_0^T e^{-p T} \cdot e^{-p u} F(u) d u=e^{-p T} \int_0^T e^{-p u} F(u) d u\)

By changing the dummy variable u to ‘ t’, we get \(\int_T^{2 T} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=e^{-p T} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)

Similarly in the third integral, butting t=u+2 T, we have \(\int_{2 T}^{3 T} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\int_0^T e^{-p(u+2 T)} F(u+2 T) d u\)

= \(\int_0^T e^{-p u} \cdot e^{-2 p T} F(u) d u\)

= \(e^{-2 p T} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t \rightarrow\)(3)

Repeating the same substitution and replacing the integrals by equations (2). (3) and so on, we get \(L[F(t)]=\int_0^T e^{-p} F(t) d t+e^{-p T} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t+e^{-2 p T} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t\)

+ \(e^{-3 p T} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t+\cdots \text { to } \infty\)

= \(\left(1+e^{-p T}+e^{-2 p T}+e^{-3 p T}+\cdots \infty\right) \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\frac{1}{1-e^{-p T}} \int_0^T e^{-p t} \cdot F(t) d t\)

114. Find the Laplace transform of the triangular wave of period ‘ 2a ‘ given by \(F(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{cl}

t, & 0<t<a \\

2 a-t, & a<t<2 a

\end{array}\right.\)

Solution:

In this case, the period is T=2 a.

L\([F(t)]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-p T}} \int_0^T e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 a p}}\left[\int_0^a e^{-p t} F(t) d t+\int_a^{2 a} e^{-p t} F(t) d t\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 a p}}\left[\int_0^a e^{-p t} \cdot t d t+\int_a^{2 a} e^{-p t}(2 a-t) d t\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 a p}}\left[t \cdot\left(\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p}\right)-1\left(\frac{e^{-p t}}{p^2}\right)_0^a+\left\{(2 a-t)\left(\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p^p}\right)-(-1)\left(\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p^2}\right)\right\}_a^{2 a}\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 a p}}\left[\frac{-a e^{-p a}}{p}-\frac{e^{-p a}}{p^2}+\frac{1}{p^2}+\frac{e^{-2 a p}}{p^2}+\frac{a \cdot e^{-a p}}{p}-\frac{e^{-a p}}{p^2}\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 a p}}\left[\frac{1-2 e^{-a p}+e^{-2 a p}}{p^2}\right]=\frac{\left(1-e^{-a p}\right)^2}{p^2\left(1+e^{-a p}\right)\left(1-e^{-a p}\right)}\)

= \(\left[\frac{1-e^{-a p}}{p^2\left(1+e^{-a p}\right)}\right]=\frac{1}{p^2} \cdot \frac{\left(1-e^{-a p}\right) e^{+\frac{a p}{2}}}{\left(1+e^{-a p}\right) e^{+\frac{a p}{2}}}=\frac{1}{p^2} \cdot \frac{e^{a p / 2}-e^{-a p / 2}}{e^{a p / 2}+e^{-a p / 2}}=\frac{1}{p^2} \tanh \left(\frac{a p}{2}\right)\).

115. Find the Laplace transform of the square wave function of the period ‘ a ‘ defined as \(F(t)= \begin{cases}1, & 0<t<a / 2 \\ -1, & a / 2<t<a\end{cases}\)

Solution:

In this case, the period T=a

L\([F(t)]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-a p}} \int_0^a e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\frac{1}{1-e^{-a p}}\left[\int_0^{a / 2} e^{-p t} F(t) d t+\int_{a / 2}^a e^{-p t} F(t) d t\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-a p}}\left[\int_0^{a / 2} e^{-p t} \cdot 1 \cdot d t+\int_{a / 2}^a e^{-p t} \cdot(-1) d t\right]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-a p}}\left[\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p}\right]_0^{a / 2}-\left[\frac{e^{-p t}}{-p}\right]_{a / 2}^a\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-a p}}\left[\frac{e^{-p a / 2}}{-p}+\frac{1}{p}+\frac{e^{-a p}}{p}-\frac{e^{-p a / 2}}{p}\right]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-a p}} \cdot \frac{1-2 e^{-\frac{a p}{2}}+e^{-a p}}{p}=\frac{1}{p}\left[\frac{1+2 e^{-\frac{a p}{2}}+e^{-a p}}{1-e^{-a p}}\right]\)

116. Find the Laplace transform of the output of a full sine wave rectifier given as : \(F(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}

\sin w t, & 0<t<\pi / w \\

0, & t>\pi / w

\end{array}\right.\)

Solution:

The period T = \(\frac{\pi}{w}\)

L\([F(t)]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-p \pi / w}} \int_0^{\pi / w} e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\frac{1}{1-e^{-p \pi / w}} \int_0^{\pi / w} e^{-p t} \cdot E \sin w t \cdot d t\)

= \(\frac{E}{1-e^{-p \pi / w}}\left[\frac{e^{-p t}}{p^2+w^2}(-p \sin w t-w \cos w t)\right]_0^{\pi / w}\)

= \(\frac{E}{\left(1-e^{-p \pi / w}\right)\left(p^2+w^2\right)}\left[e^{-p \pi / w} \cdot w+w\right]=\frac{E w}{\left(1-e^{-p \pi / w}\right)\left(p^2+w^2\right)}\left(1+e^{-p \pi / w}\right)\)

= \(\frac{E w}{\left(p^2+w^2\right)} \cdot\left[\frac{e^{p \pi / 2 w}+e^{-p \pi / 2 w}}{e^{p \pi / 2 w}-e^{-p \pi / 2 w}}\right]=\frac{E w}{p^2+w^2} \cosh (p \pi / 2 w)\)

117. Find the Laplace transform of \(F(t)=e^{-t}, 0<t<2, F(t+2)=F(t)\).

Solution:

In this case, the period T=2

∴ \(L[F(t)]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 p}} \int_0^2 e^{-p t} F(t) d t=\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 p}} \int_0^2 e^{-p t} e^{-t} d t=\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 p}} \int_0^2 e^{-(p+1) t} d t\)

= \(\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 p}}\left[\frac{e^{-(p+1) t}}{-(p+1)}\right]_0^2=\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 p}}\left[\frac{e^{-2(p+1)}}{-(p+1)}+\frac{1}{p+1}\right]=\frac{1}{1-e^{-2 p}}\left[1-\frac{e^{-2(p+1)}}{p+1}\right]\)

118. Find the Laplace transform of the function F(t)=1,0<t<2; F(t)=2,2<t<4; F(t)=3,4<t<6;F(t)=0, t>6.

Solution:

F(t) = \(1[u(t-0)-u(t-2)]+2[u(t-2)-u(t-4)]+3[u[t-4]-u(t-6)]\)

= \(u(t-0)+u(t-2)+u(t-4)-3 u(t-6)\)

L\(\{F(t)\}=L\{u(t-0)\}+L\{u(t-2)\}+L\{u(t-4)\}-3 L\{u(t-6)\}\)

= \(\frac{1}{p}+\frac{e^{-2 p}}{p}+\frac{e^{-4 p}}{p}-\frac{3 e^{-6 p}}{p}\)

119. Find the Laplace Transform of the square-wave function of period 2a defined as \(F(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}

k \text { when } 0<t<a \\

-k \text { when } a<t<2 a

\end{array}\right.\)

Solution:

Since F(t) is a periodic function with period T=2 a