Chapter 3 The Plane

Definition Of A Plane In Geometry With Examples And Proofs

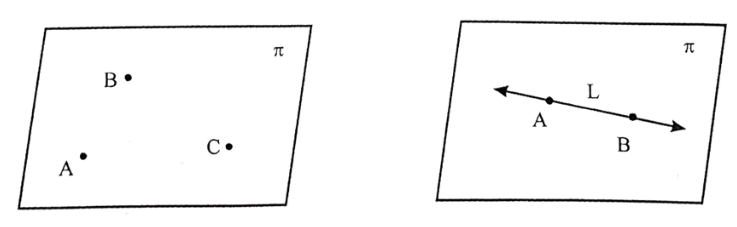

Definition: A Plane is a surface such that if any two points are taken on it, the line joining them lies wholly on the surface.

Theorem.1 Every equation of the first degree in x, y, z represents a plane.

Proof. Let ax + bx + cz + d = 0, a2 + b2 + c2 ≠ 0 …..(1)

be the first-degree equation in x, y, z.

If we have to show that (1) represents the equation to the plane, we prove that every point on the line joining any two points on (1) also lies on the locus (1).

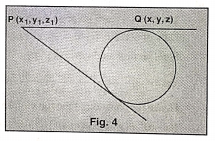

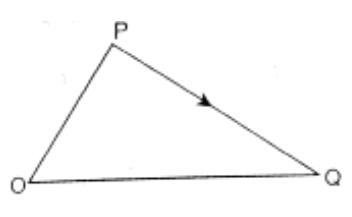

Let p(x, y, z) and Q(x2, y2, z2) be any two points on the locus (1).

Then we have ax1 + bx1 + cz1 + d = 0 …..(2)

and ax2 + by2 + cz2 + d = 0 …..(3)

Let R be any point on the line segment joining the points P and Q. Suppose R divides PQ in the ratio K : 1.

then \(\mathrm{R}=\left(\frac{\mathrm{K} x_2+x_1}{\mathrm{~K}+1}, \frac{\mathrm{K} y_2+y_1}{\mathrm{~K}+1}, \frac{\mathrm{K} z_2+z_1}{\mathrm{~K}+1}\right), \mathrm{K}+1 \neq 0\)

We have to show that R lies on the locus (1) for all values of K(≠ -1).

Substituting the coordinates of R in the LHS of (1), we get

⇒ \(\frac{a\left(\mathrm{~K} x_2+x_1\right)}{\mathrm{K}+1}+\frac{b\left(\mathrm{~K} y_2+y_1\right)}{\mathrm{K}+1}+\frac{c\left(\mathrm{~K} z_2+z_1\right)}{\mathrm{K}+1}+d\)

= a(Kx2 + x1) + b(Ky2 + y1) + c(Kz2 + z1) + d(K + 1)

= K(ax2 + by2 + cz2 + d) + (ax1 + by1 + cz1 + d) = K(0) + = 0 which shows that R lies on the locus (1).

Since R is an arbitrary point on the line joining P and Q, every point on PQ lies on (1)

∴ The equation ax + by + cz + d = 0, a2 + b2 + c2 ≠ 0 always represents a plane.

Chapter 3 The Plane Converse Of The Above Theorem

Theorem.2 The equation to every plane is of the first degree in x, y, z.

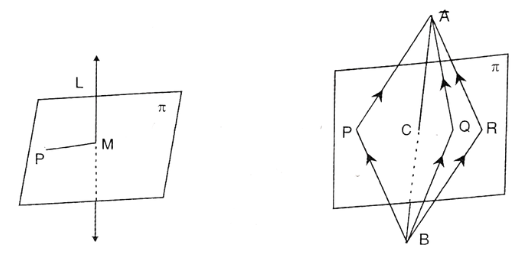

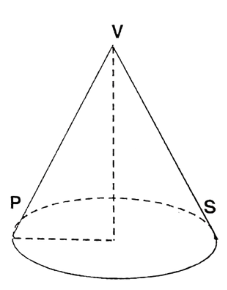

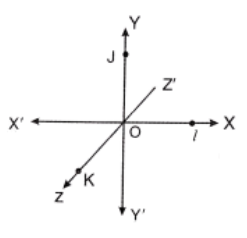

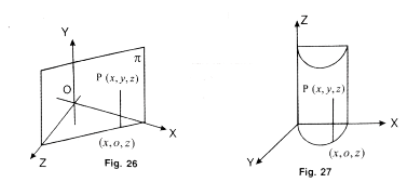

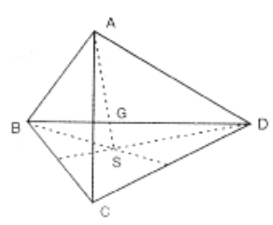

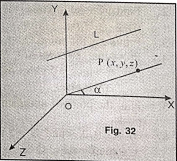

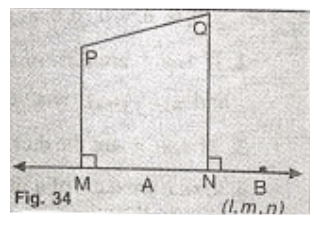

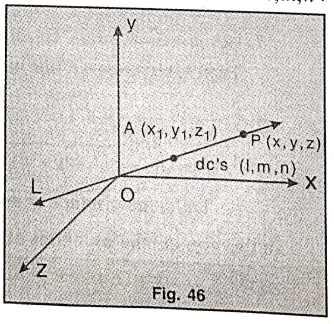

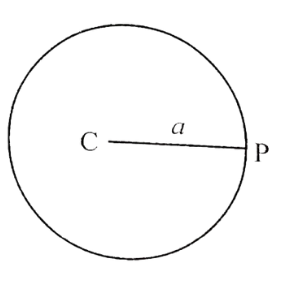

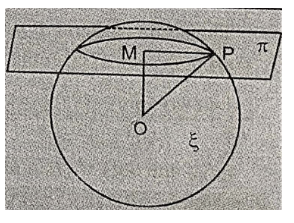

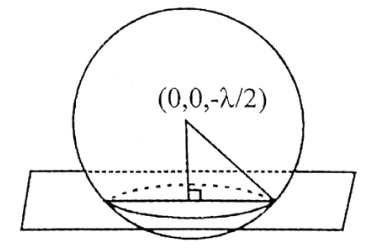

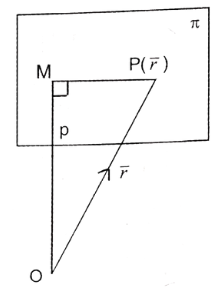

Proof. Let π be the plane and O be the origin.

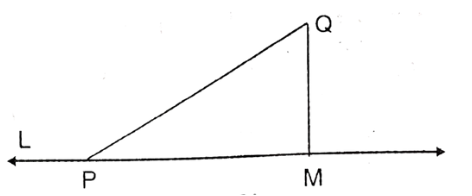

Case(1). Let O ∉ π, and let M be the foot of the perpendicular from O in π.

Let OM = p (>0). Let p(x, y, z) be any point in the plane.

Let [l, m, n] be Dc’s of the perpendicular OM.

p ≠ M. jOIN OP. OM = Projection of OP along OM

⇒ p = l(x-0)+m(y-0)+n(z-0) = lx+my+nz

Case.(2). Let O ∈ π, then p = 0.

p ∈ π <=> lx + my + nz = 0 <=> lx + my + nz = p where p = 0

Since any point P on π satisfies the equation lx + my + nz = p

it represents the equation of the plane.

The equation to π is lx + my + nz = p where p ≥ 0.

Hence the equation to the plane lx + my + nz = p is a first-degree equation in x, y, z.

Note.

1. If O ∈ π, equation to the plane is lx + my nz = 0.

2. lx + my + nz = p is called the normal form of the equation to the plane. Coefficients of x, y, z in the equation are l, m, n, and [l, m,n] are Dc’s of the normal OM to the plane, where p(≥ 0) is the distance of the origin to the plane.

3. An equation to the plane, in general, is taken as ax + by + cz + d = 0.

Theorems Related To Planes With Solved Problems Step-By-Step

Theorem: The Plane Transformation Of The Equation To The Plane Into The Normal Form

Let the equation to the plane be ax + by + cz + d = 0, a2 + b2 + c2 ≠ 0 …..(1)

We can take d ≥ 0 or d ≤ 0.

ax + by + cz + d = 0 <=> ax + by + cz = -d. Dividing by \(\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}\), we get

⇒ \(\frac{-a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}+\frac{-b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}+\frac{-c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}=\frac{d}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\) …..(2)

or \(\frac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} x+\frac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} y+\frac{c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} z=-\frac{d}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\) …..(3)

This ((3) or (2)) is of the form lx + my + nz = p [p ≥ 0]

Where \([l=\pm \frac{a}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}, m=\pm \frac{b}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}, n=\pm \frac{c}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}, p=\mp \frac{d}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}]\)

∴ The normal form of the equation to the plane (1) is

⇒ \(\pm \frac{a x}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}} \pm \frac{b y}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}} \pm \frac{c z}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}=\mp \frac{d}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}(d \leq 0 \text { or } d \geq 0)\)

Note.

1. Direction ratios of a normal to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 are (a, b, c).

i.e., the coefficients of x, y, z in the equation.

2. Distance of the origin from the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 is \(\frac{|d|}{\sqrt{\left(a^2+b^2+c^2\right)}}\)

3. First-degree equation in x, y, z without constant term <=> plane is passing through the origin.

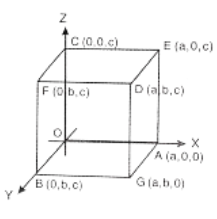

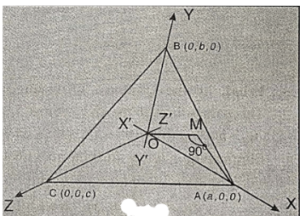

4. abc ≠ 0 and \(\left(\frac{1}{a}\right) x+\left(\frac{1}{b}\right) y+\left(\frac{1}{c}\right) z+(-1)=0\). This equation represents a plane intersecting the x-axis in the point (a, 0, 0), intersecting the y-axis in the point (0, b, 0), and intersecting the z-axis in the point (0, 0, c).

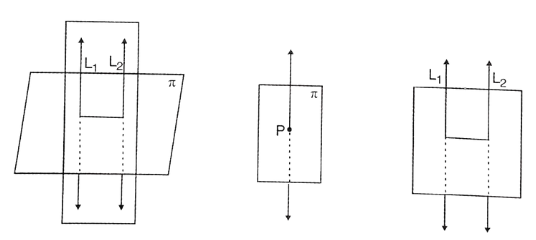

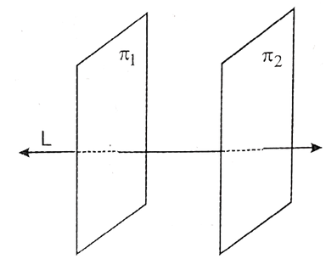

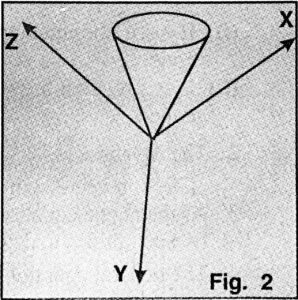

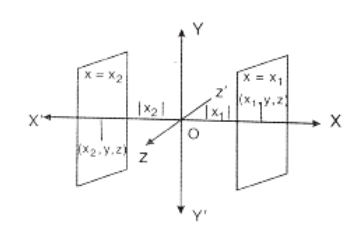

Chapter 3 The Plane (1). Consider the equation lx + my = p (l≠0, m≠0) of a plane (π), d.cs. of a normal to it being l,m,0. Since 0, 0, 1 are dc.s. of the z-axis and l.0+m.0+0.1 = 0, the normal to π is perpendicular to the z-axis i.e., π is parallel to the z-axis.

Hence lx + my = p is the equation to a plane parallel to the z-axis.

Similarly, lx + my = p is the equation to a plane parallel to the y-axis and my + nz = p is the equation to a plane parallel to the x-axis.

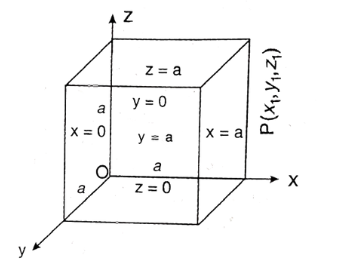

(2) Consider the equation lx = p(l≠0) of a plane (π), d.cs. of a normal to it being l, 0, 0. Since o, 1, 0 are d.cs. of the y-axis i.e., π is parallel to the y-axis. Similarly, π is also parallel to the z-axis. Hence π is a plane parallel to the yz plane (x=0).

Similarly, my = p is a plane parallel to the zx plane (y=0) and nz = p is a plane parallel to the xy plane (z=0).

Orthogonal Projection Of Points And Lines On Planes Examples

Theorem.3 If the equation a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 represents the same plane, then a1:b1:c1:d1 = a2:b2:c2:d2.

Proof. Given equations are a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 …..(1)

a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 …..(2)

∴ (a1, b1, c1), (a2, b2, c2) are d.rs. of normals to the same plane.

Since the normals are either equal (coincident) or parallel,

we have a1:a2 = b1:b2 = c1:c2 = λ(say) (λ≠0) or (a1, b1, c1)=λ(a2, b2, c2)

Let (x1, y1, z1) be any point in the plane represented by (1) and (2).

∴ d1 = -(a1x1 + b1y1 + c1z1)

= -(a1, b1, c1).(x1, y1, z1) = -λ(a2, b2, c2).(x1, y1, z1)

= -λ(a2x1 + b2y1 + c2z1) = -λd2

∴ a1:a2 = b1:b2 = c1:c2 = d1:d2

Chapter 3 Angles Between Two Planes

Definition. Angles between two planes are equal to the angles between their normals.

Angles between the planes a1x + b1y + c1z = d1 , a2x + b2y + c2z = d2

Let the equation to the planes be a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 …..(1)

a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 …..(2)

Dc’s of the normal to (1) =

⇒ \(m_1=\left(\frac{a_1}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)}}, \frac{b_1}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)}}, \frac{c_1}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)}}\right)\) and

Dc’s of the normal to (2) =

⇒ \(m_2=\left(\frac{a_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_2{ }^2+b_2{ }^2+c_2{ }^2\right)}}, \frac{b_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_2{ }^2+b_2{ }^2+c_2{ }^2\right)}}, \frac{c_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_2{ }^2+b_2{ }^2+c_2{ }^2\right)}}\right)\)

Let θ be one of the angles between the planes.

∴ θ = one of the angles between the normals m1, m2

=\(\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)} \sqrt{\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)}}\right)\)

The other angle between the planes is 180° – θ.

Cor.1. Condition of parallelism.

Planes are parallel ⇒ θ = 0° or 180° ⇒ \(\pm 1=\frac{a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)} \sqrt{\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)}}\)

⇒ \(\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)=\left(a_1 a_2+b_1 b_2+c_1 c_2\right)^2\)

⇒ a12b22 + a12c22 + b12a22 + b12c22 + c12a22 + c12b22 – 2a1a2b1b2 – 2b1b2c1c2 – 2c1c2a1a2 = 0

⇒ \(\left(a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1\right)^2+\left(b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1\right)^2+\left(c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1\right)^2=0\)

⇒ \(a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1=b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1=c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1=0 \Rightarrow a_1: a_2=b_1: b_2=c_1: c_2\)

OR: Planes are parallel ⇒ their normals are parallel

⇒ d.rs of normals are proportional ⇒ a1:a2 = b1:b2 = c1:c2.

Cor. 2. Condition of perpendicularity.

Planes are perpendicular ⇒ θ = 90° ⇒ a1a2 + b1b2 + c1c2 = 0.

example. The plane x + 2y – 3z + 4 = 0 is perpendicular to the plane 2x + 5y + 4z + 1 = 0

since (1)(2) + (2)(5) + (-3)(4) = 0

OR: Planes are perpendicular ⇒ their normals are perpendicular

⇒ (a1, b1, c1).(a2, b2, c2) = 0 ⇒ a1a2 + b1b2 + c1:c2 = 0

Note.

1. The equation a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a1x + b1y + c1z + d2 = 0 represent a pair of parallel planes.

2. A plane parallel to ax + by + cz + d = 0 is ax + by + cz + d = k, where k is an unknown real number.

example 1. The equation of the plane through the point (x1, y1, z1) and parallel to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 is ax + by + cz = a1x + b1y + c1z .

example 2. The normals to the plane as x – y + z – 1 = 0, 3x + 2y – z + 2 = 0 are perpendicular since (1)(3) + (-1)(2) + 1(-1) = 0.

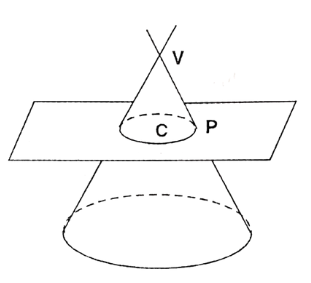

Chapter 3 The Plane Determination Of A Plane Under Given Conditions

Consider the equation ax + by + cz + d = 0 of a plane. Since (a, b, c) ≠ (0, 0, 0), without loss of generally, we can take a≠0.

∴ Equation of the plane is \(x+\frac{b}{a} y+\frac{c}{a} z+\frac{d}{a}=0\)

∴ To know uniquely \(\frac{b}{a}, \frac{c}{a}, \frac{d}{a}\) we require three conditions.

For example, we can find the equation to a plane, if (1) three non-collinear points in the plane are given. (2) if two points in the plane and a plane perpendicular to the required plane (3) if one point in the plane and two planes perpendicular to the required plane are given.

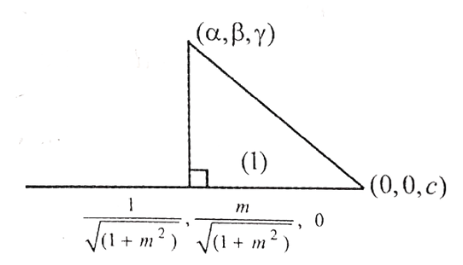

Definition. If a plane π intersects the coordinate axes at (a, 0, 0), (0, b, 0), (0, 0, c) then a, b, c are respectively called the x-intercept, the y-intercept, the z-intercept of the plane π.

If the plane lx + my + nz = p intersects the x-axis at (a, 0, 0) then its x-intercept = a = \(\frac{p}{l}\).

Similarly its y-intercept = b = \(\frac{p}{m}\), its z-intercept = c = \(\frac{p}{n}\)

Note. If abc ≠ 0 and ax + by + cz + d = 0 …..(1) is a plane, then its x-intercept = \(-\frac{d}{a}\), (by putting y = 0, z = 0 in (1))

y-intercept = \(-\frac{d}{b}\), z-intercept = \(-\frac{d}{c}\).

example. The intercepts made by the plane x – 12y – 2z = 9 with the axes are \(\frac{9}{1},-\frac{9}{12},-\frac{9}{2}, \text { i.e., } 9,-\frac{3}{4},-\frac{9}{2}\).

Step-By-Step Solutions For Orthogonal Projection Problems On Planes

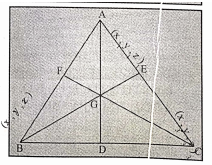

Theorem.4 Equation to the plane making intercepts a, b, c on the coordinate axes is \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1\).

Proof. Let π be the plane making intercepts,

a, b, c on the coordinate axes

Let A = (a, 0, 0), B = (0, b, 0), and C = (0, 0, c).

∴ abc ≠ 0.

Clearly, A, B, C are non-collinear. Let the equation to the plane π in the normal form be

lx + my + nz = p …..(1)

Let M be the foot of the perpendicular

from O to π and let [l, m, n] be the Dc’s of OM. Let OM = p.

p = OM = Projection of OA on OM = al.

Similarly p = bm, and p = cn. ∴ From(1)

equation to the plane π is \(\frac{p}{a} x+\frac{p}{b} y+\frac{p}{c} z=p \Rightarrow \frac{x}{a}+\frac{x}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1\) (∵ p ≠ 0)

Note. Equation to the plane ABC is \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1\). This is called the intercept form of the equation to the plane and this plane does not pass through the origin.

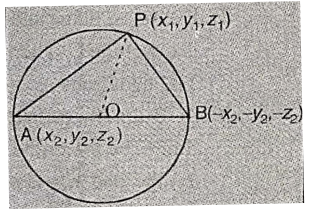

OR: Let A = (a, 0, 0), B = (0, b, 0), C = (0, 0, c). Let \(\mathrm{P}=\bar{r}=(x, y, z)\).

Now A, B, C are non-collinear. \(P \in \overleftrightarrow{A B C}(P \neq A \text { or } P=A)\) (∵ abc ≠ 0)

<=> \(\overline{\mathrm{AP}}, \overline{\mathrm{AB}}, \overline{\mathrm{AC}}\) are coplanar or \(\overline{\mathrm{AP}}(=\overline{0}), \overline{\mathrm{AB}}, \overline{\mathrm{AC}}\) are three vectors.

<=> \(\bar{r}-\bar{a}(\neq \overline{0}), \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}\) are coplanar or \(\bar{r}-\bar{a}(=\overline{0}), \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}\) are three vectors.

<=> [(x-a, y, z),(-a, b, 0), (-a, 0, c)] = 0

<=> \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-a & y & z \\

-a & b & 0 \\

-a & 0 & c

\end{array}\right|=0 \Leftrightarrow(x-a) b c+y a c+z a b=0\)

<=> \(\frac{x}{a}-1+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=0 \)

<=> \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1\).

∴ Equation to \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}} \text { is } \frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1\).

Note. \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1\) is called the intercept form of the equation of the plane and this plane does not pass through the origin.

Properties Of Planes And Their Orthogonal Projections With Examples

Theorem. Equation to the plane determined by three non-collinear points A(x1, y1, z1), B(x2, y2, z2), C(x3, y3, z3) is

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{llll}

x & y & z_1 & 1 \\

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 & 1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2 & 1 \\

x_3 & y_3 & z_3 & 1

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Proof. Let the equation of the required plane be ax + by + cz + d = 0 …..(1)

This passes through the given points if a1x + b1y + c1z + d = 0 …..(2)

a2x + b2y + c2z + d = 0 …..(3) ax3 + by3 + cz3 + d = 0 …..(4)

Eliminating a, b, c, d from the above equations (1), (2), (3), (4), we have

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{llll}

x & y & z & 1 \\

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 & 1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2 & 1 \\

x_3 & y_3 & z_3 & 1

\end{array}\right|=0\) …..(5)

This is the equation to the required plane.

OR :

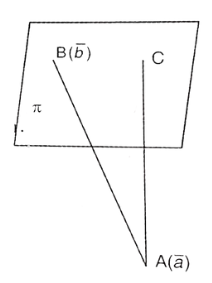

Proof. Let \(\mathrm{A}=\bar{a}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \quad \mathrm{B}=\bar{b}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right), \mathrm{C}=\bar{c}=\left(x_3, y_3, z_3\right)\)

Let \(\bar{r}=(x, y, z) . \quad \bar{r}(\neq \bar{a}) \in \pi, \bar{r}(=\bar{a}) \in \pi\)

<=> \(\bar{r}-\bar{a}, \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}\) are coplanar or \(\bar{r}-\bar{a}(=\overline{0}), \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}\) are three vectors

<=> \( [\bar{r}-\bar{a}, \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}]=0\)

<=> \(\left[\left(x-x_1, y-y_1, z-z_1\right),\left(x_2-x_1, y_2-y_2, z_2-z_1\right),\left(x_3-x_1, y_3-y_1, z_3-z_1\right)\right]=0\)

<=> \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

x_2-x_1 & y_2-y_1 & z_2-z_1 \\

x_3-x_1 & y_3-y_1 & z_3-z_1

\end{array}\right|=0\) …..(1)

<=> \(\left|\begin{array}{cccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 & 0 \\

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 & 1 \\

x_2-x_1 & y_2-y_1 & z_2-z_1 & 0 \\

x_3-x_1 & y_3-y_1 & z_3-z_1 & 0

\end{array}\right|=0\)

<=> \(\left|\begin{array}{cccc}

x & y & z & 1 \\

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 & 1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2 & 1 \\

x_3 & y_3 & z_3 & 1

\end{array}\right|=0 \mid \begin{aligned}

& \mathrm{R}_2+\mathrm{R}_1 \\

& \mathrm{R}_3+\mathrm{R}_1 \\

& \mathrm{R}_4+\mathrm{R}_1

\end{aligned}\)

Note. equation (1) may also be taken as the equation of the required plane.

Note. If the points (x1, y1, z1), (x2, y2, z2), (x3, y3, z3), (x4, y4, z4) are such that

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{llll}

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 & 1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2 & 1 \\

x_3 & y_3 & z_3 & 1 \\

x_4 & y_4 & z_4 & 1

\end{array}\right|=0\), then the points are coplanar.

⇒ If \(\left|\begin{array}{llll}

x_1 & y_1 & z_1 & 1 \\

x_2 & y_2 & z_2 & 1 \\

x_3 & y_3 & z_3 & 1 \\

x_4 & y_4 & z_4 & 1

\end{array}\right| \neq 0\), then the points are non-coplanar.

Applications Of Orthogonal Projection On Planes In Mathematics

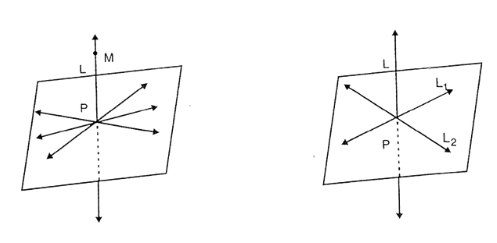

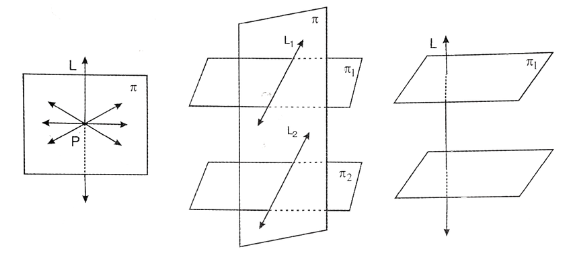

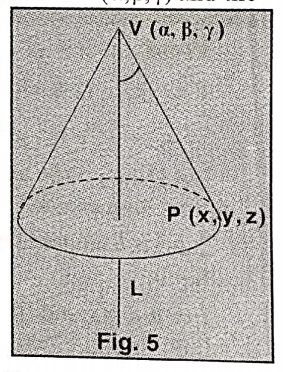

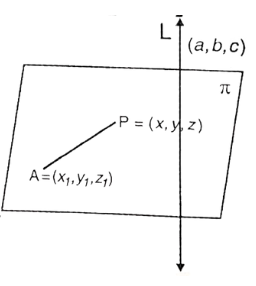

Theorem. Equation to the plane (π) through the point A(x1, y1, z1) and perpendicular to the line (L) with d.rs. (a, b, c) is a(x-x1)+b(y-y1)+c(z-z1) = 0.

Proof: Let p ∈ π and p = (x, y, z). A = (x1, y1, z1)

and d.rs. of L are (a, b, c)

Now d.rs. of AP = (x – x1, y – y1, z – z1).

⇒ \(\overleftrightarrow{A P} \in \pi \Leftrightarrow \overleftrightarrow{A P} \perp L\)

<=> a(x-x1) + b(y-y1) + c(z-z1) = 0

∴ Equation to π is a(x – x1) + b(y – y1) + c(z – z1) = 0.

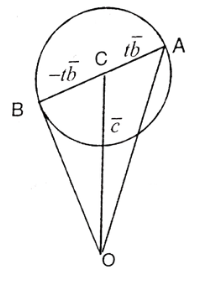

Chapter 3 The Plane Parametric Equation Of A Plane

Theorem. An equation to the plane passing through three non-collinear points A(a), B(b), C(c) is r = (1 – t – s) a + sb + tc, where s, t are any scalars (real numbers)

Proof: \(\bar{r} \in \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}} \Rightarrow \bar{r}-\bar{a}, \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}\) are coplanar;

or \(\bar{r}-\bar{a}(\not 0), \bar{b}-\bar{a}, \bar{c}-\bar{a}\) are three vectors

<=> \(\bar{r}-\bar{a}=s(\bar{b}-\bar{a})+t(\bar{c}-\bar{a})\) where s, t are any scalars

<=> \(\bar{r}=(1-s-t) \bar{a}+s \bar{b}+t \bar{c}\) is the equation of the plane through \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}\).

Note. Let \(\bar{r}=(x, y, z), \bar{a}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \bar{b}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right), \bar{c}=\left(x_3, y_3, z_3\right)\)

Then parametric equation to the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}\) is

(x, y, z) = (1 – s – t)( x1, y1, z1) + s(x2, y2, z2) + t(x3, y3, z3)

i.e. x = x1 + s(x2 – x1) + t(x3 – x1),

y = y1 + s(y2 – y1) + t(y3 – y1)

z = z1 + s(z2 – z1) + t(z3 – z1)

Cor. Points \(\bar{a}, \bar{b}, \bar{c}, \bar{d}\) are coplanar

<=> \(\overline{\bar{d}}=(1-s-t) \bar{a}+s \bar{b}+t \bar{c}\)

<=> \((1-s-t) \bar{a}+s \bar{b}+t \bar{c}+(-1) \bar{d}=0\)

<=> \(\lambda_1 \bar{a}+\lambda_2 \bar{b}+\lambda_3 \bar{c}+\lambda_4 \bar{d}=0\),

λ1 + λ2 + λ3 + λ4= 1 – s – t + s + t – 1 = 0 and (λ1 + λ2 + λ3 + λ4) ≠ (0, 0, 0, 0)

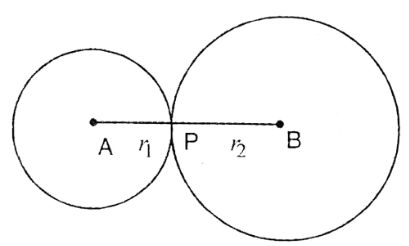

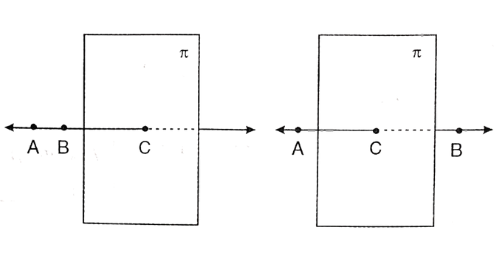

Chapter 3 The Plane Two Sides Of A Plane

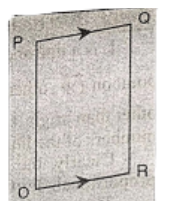

A Plane π divides the space into two half-spaces. Let a line \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) intersect π in C. If A, B are in the same half-space, then (C; A, B) is negative, and A, B lie on the same side of C. If A, B are in different half spaces, then (C; A, B) is positive, and A, B lie on either side of C.

Theorem. If the line through A(x1, y1, z1) and B(x2, y2, z2) intersect the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 in C, then (C; A, B) = -(a1x + b1y + c1z + d):(a2x + b2y + c2z + d).

Proof. Let A = (x1, y1, z1) and B = (x2, y2, z2) and C divide AB in the ratio λ1 : λ2 (λ1 + λ2 ≠ 0).

∴ (C; A, B) = λ1 : λ2 (λ1 + λ2 ≠ 0) and

⇒ \(\mathrm{C}=\left(\frac{\lambda_2 x_1+\lambda_1 x_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, \frac{\lambda_2 y_1+\lambda_1 y_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}, \frac{\lambda_2 z_1+\lambda_1 z_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right)\)

⇒ \(\mathrm{C} \in \pi \Leftrightarrow a\left(\frac{\lambda_2 x_1+\lambda_1 x_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right)+b\left(\frac{\lambda_2 y_1+\lambda_1 y_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right)+c\left(\frac{\lambda_2 z_1+\lambda_1 z_2}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right)+d=0\)

<=> \(\lambda_2\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right)+\lambda_1\left(a x_2+b y_2+c z_2+d\right)=0\)

<=> \(\lambda_1\left(a x_2+b y_2+c z_2+d\right)=-\lambda_2\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right)\)

<=> \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2=-\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right):\left(a x_2+b y_2+c z_2+d\right)\)

<=> \((\mathrm{C} ; \mathrm{A}, \mathrm{B})=-\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right):\left(a x_2+b y_2+c z_2+d\right)\)

OR :

Proof: Let \(\mathrm{A}=\bar{a}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \text { and } \mathrm{B}=\bar{b}=\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\)

Let \(\mathrm{C}=\bar{c}\) divide AB in the ratio λ1 : λ2.

∴ (C; A, B) = λ1 : λ2 (λ1 + λ2 ≠ 0)

Then \(\bar{c}=\frac{\lambda_2 \bar{a}+\lambda_1 \bar{b}}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\)

Let the plane represented by ax + by + cz + d = 0 be \(\bar{r} \cdot \bar{m}=q\) where

⇒ \(\bar{r}=(x, y, z), \bar{m}=(a, b, c) \text { and } q=-d\)

∴ \(\mathrm{C} \in \pi \Leftrightarrow \bar{c} \cdot \bar{m}-q=0\)

<=> \(\left(\frac{\lambda_2 \bar{a}+\lambda_1 \bar{b}}{\lambda_1+\lambda_2}\right) \cdot \bar{m}-q=0\)

<=> \(\lambda_2(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{m})+\lambda_1(\bar{b} \cdot \bar{m})=q \lambda_1+q \lambda_2 \Leftrightarrow \lambda_1(\bar{b} \cdot \bar{m}-q)=-\lambda_2(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{m}-q)\)

<=> \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2=-(\bar{a} \cdot \bar{m}-q):(\bar{b} \cdot \bar{m}-q)\)

<=> \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2=-\left\{\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \cdot(a, b, c)+d\right\}:\left\{\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right) \cdot(a, b, c)+d\right\}\)

<=> \(\lambda_1: \lambda_2=-\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right):\left(a x_2+b y_2+c z_2+d\right)\)

<=> \((\mathrm{C} ; \mathrm{A}, \mathrm{B})=-\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right):\left(a x_2+b y_2+c z_2+d\right)\)

Note 1. A, B lie in the same half-space.

<=> a1x + b1y + c1z + d, a2x + b2y + c2z + d are of the same sign and A, B lie in the different half-spaces.

<=> a1x + b1y + c1z + d, a2x + b2y + c2z + d are of the different signs.

example

1. The points (1, 2, -5), (0, 4, -7) lie in the different half space (on the opposite sides) of the plane x + 2y + 2z – 9 = 0 since 2 + 2(3) + 2(5) – 9 > 0 and 0 + 2(4) + 2(-7) – 9 <0.

2. The points (1, 2, -5),(0, 4, -7) lie in the same half-space (on the same side) of the plane x + 2y + 2z – 9 = 0 since (1) + 2(2) + 2(-5) – 9 < 0 and 0 + 2(4) + 2(-7) – 9 < 0.

3. The points (1, -1, 3) and (3, 3, 3) lie on different sides of the plane x + 2y – 7z + 9 = 0 since 5(1) + 2(-) – 7(3) + 9 = -9 < 0 and 5(3) + 2(3) – 7(3) + 9 = 9 > 0.

Worked Examples Of Orthogonal Projection Onto Planes In Geometry

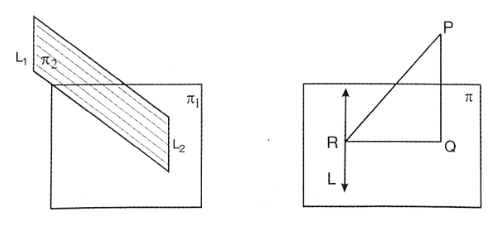

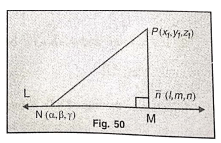

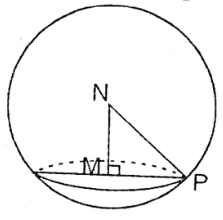

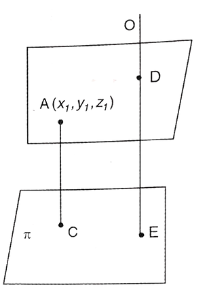

Chapter 3 The Plane Perpendicular Distance Of A Point From A Plane

Theorem. The distance of A(x1, y1, z1) from the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 i.e. length of the perpendicular from the point A(x1, y1, z1) to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 is

⇒ \(\frac{\left|a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right|}{\sqrt{\left(a^2+b^2+c^2\right)}}\).

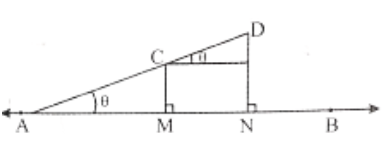

Proof: Let π be the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 …..(1)

Let A = (x1, y1, z1) be the point (A ∉ π) from which the perpendicular drawn to the plane π meets it in C.

Let the normal form of π be lx + my + nz = p …..(2)

the equation to the plane parallel to (2) and passing through the point A be

lx + my + nz = p1 …..(3) where lx1 + my1 + nz1 = p1 …..(4)

Let ODE be perpendicular to (2) and (3) as shown.

⇒ AC = p1 – p

⊥r distance of A to the plane π

= AC = OE – OD = lx1 + my1 + nz1 – p

= \(+\frac{a}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}} x_1+\frac{b}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}} y_1+\frac{c}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}} z_1 \pm \frac{d}{\sqrt{\sum a^2}}\)

i.e., \(\pm \frac{\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right)}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} \text { or } \frac{\left|a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\)

OR : Proof: Let \(\mathrm{A}=\bar{a}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\).

Let π be the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0.

Equation to π can be taken as \(\bar{r} \cdot \bar{m}=q \text { where } \bar{r}=(x, y, z)\).

⇒ \(\bar{m}=(a, b, c) \text { and } q=-d\).

Now, \(|\bar{m}|=\sqrt{\left(a^2+b^2+c^2\right)}\).

Let C be the foot of the perpendicular from A to π.

Let B(≠C) be \(\bar{b}\) in π.

∴ \(\bar{b} \cdot \bar{m}=q\) …..(1)

∴ \(\mathrm{AC}=\frac{|\overline{\mathrm{AB}} \cdot \overline{\mathrm{AC}}|}{|\overline{\mathrm{AC}}|}=\frac{|(\bar{b}-\bar{a}) \cdot \bar{m}|}{|\bar{m}|}=\frac{|\bar{b} \cdot \bar{m}-\bar{a} \cdot \bar{m}|}{|\bar{m}|}=\frac{|\bar{a} \cdot \bar{m}-\bar{b} \cdot \bar{m}|}{|\bar{m}|}=\frac{|\bar{a} \cdot \bar{m}-\bar{q}|}{|\bar{m}|}\)

= \(\frac{\left|\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \cdot(a, b, c)-q\right|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}=\frac{\left|a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\)

example. The distance of the points (2, 3, 4) and (1, 1, 4) from the plane 3x – 6y + 2z + 11 = 0

=\(\left|\frac{3(2)-6(3)+2(4)+11}{\sqrt{(9+36+4)}}\right|=1 \text { and }\left|\frac{3-6+8+11}{\sqrt{9+36+4}}\right|=\frac{16}{7}\)

Chapter 3 The Plane Distance Between Parallel Planes

Theorem. Distance between parallel planes ax + by + cz + d1 = 0, ax + by + cz + d2 = 0 is \(\frac{\left|d_1-d_2\right|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\), d1 < 0, d2 > 0.

Proof. The equations to the planes are

ax + by + cz + d1 = 0 …..(1) ax + by + cz + d2 = 0 …..(2)

the Dc’s of the normal to the planes are

⇒ \(\left(\frac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}, \frac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}, \frac{c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\right)\)

Now p1 and p2 be the perpendicular distances to the planes from the origin

⇒ \(p_1=\frac{-d_1}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}, p_2=\frac{-d_2}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\)

⇒ Distance between the parallel planes = \(\left|p_1-p_2\right|=\frac{\left|d_2-d_1\right|}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\).

Note. Equation to the plane parallel to (1) and (2) and midway between (1) and (2)

(1) When the origin lies on the same side of both (1) and (2) is

i.e., \(a x+b y+c z=\frac{-\left(d_1+d_2\right)}{2}\)

(2) When origin lies in between (1) and (2) is \(ax+by+c z=\frac{\left|d_1-d_2\right|}{2}\)

example. The distance between the planes 2x – y + 3z = 6 and -6x + 3y – 9z = 5

= The distance between the planes 2x – y + 3z = 6 and \(2 x-y+3 z=-\frac{5}{3}\)

=\(\frac{\left|6-\left(-\frac{5}{3}\right)\right|}{\sqrt{(4+1+9)}}=\frac{23}{3 \sqrt{14}}\)

Chapter 3 The Plane Solved Problems

Example. 1. Find the point P equidistant from A(4, -3, 7) and B(2, -1, 1) and lying on y-axis. Hence find the equation to the plane through P and perpendicular to \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\).

Solution:

Given

A(4, -3, 7) and B(2, -1, 1)

Let P = (0, y, 0). Since PA = PB, PA2 = PB2

⇒ (0 – 4)2 + (y + 3)2 + (0 – 7)2 = 4 + (y + 1)2 + 1 ⇒ 4y = -68 ⇒ y = -17

∴ P = (0, -17, 0) and d.rs of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) are 2, -2, 6.

∴ The equation to the plane through P, and perpendicular \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) is

2(x – 0) – 2(y + 17) + 6(z – 0) = 0 i.e., 2x – 2y + 6z – 34 = 0,

i.e., x – y + 3z – 17 = 0

Geometric Interpretation Of Planes And Orthogonal Projections

Example.2. Show that the line joining the points (6, -4, 4), (0, 0, -4) intersects the line joining the points (-1, -2, -3), (1, 2, -5).

Solution.

Given

(6, -4, 4), (0, 0, -4)

And (-1, -2, -3), (1, 2, -5)

Let A = (6, -4, 4), B = (0, 0, 4), C = (-1, -2, -3), D = (1, 2, -5).

∴ \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}=(-6,4,-8) \text { and } \overline{\mathrm{CD}}=(2,4,-2)\)

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{AB}}\) is neither perpendicular not parallel to \(\overline{\mathrm{CD}}\).

∴ If we prove that A, B, C, D are coplanar, then \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) intersects \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\).

Now equation to the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}\) is \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-6 & y+4 & z-4 \\

-6 & 4 & -8 \\

-7 & 2 & -7

\end{array}\right|=0\)

⇒ (-28 + 16)(x – 6) – (42 – 56)(y + 4) + (-12 + 28)(z – 4) = 0

⇒ 6(x – 6) – 7(y + 4) – 8(z – 4) = 0 ⇒ 6x – 7y – 8z – 32 = 0 …..(1)

Substituting D in the L.H.S of (1), we get 6 – 14 + 40 – 32 = 0 = R.H.S.

∴ \(D \in \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}\)

∴ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}} \text { and } \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{CD}}\) intersect.

Example.3. Obtain the equation to the plane containing (0, 4, 3) and the line through the points (-1, -5, -3), (-2, -2, 1). Hence show that (0, 4, 3), (-1, -5, -3), (-2, -2, 1) and (1, 1, -1) are coplanar.

Solution.

Given

(0, 4, 3) (-1, -5, -3), (-2, -2, 1)

Let π be the required plane. Let a, b, c be d.rs. of a normal to it.

Let A = (0, 4, 3), B = (-1, -5, -3), C = (-2, -2, 1)

D.rs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}\) are -1, -9, -6 and d.rs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\) are -2, -6, -2.

Since \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AB}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{AC}}\) are in π,

⇒ \(\left.\begin{array}{r}

-a-9 b-6 c=0 \\

-2 a-6 b-2 c=0

\end{array}\right\} \text {. Solving, } \frac{a}{-18}=\frac{b}{10}=\frac{c}{-12} \text { i.e., } \quad \frac{a}{9}=\frac{b}{-5}=\frac{c}{6}\)

∴ Equation to π is 9(x – 0) – 5(y – 4) + 6(z – 3) = 0 i.e., 9x – 5y + 6z + 2 = 0 …..(1)

Clearly (1, 1, -1) lies on (1). Hence the points are coplanar.

∴ The equation to the plane containing the points is (1).

Example.4. Find the equation of the plane through (4, 4, 0) and perpendicular to the planes x + 2y + 2z = 5 and 3x + 3y + 3z – 8 = 0.

Solution.

Given

(4, 4, 0)

x + 2y + 2z = 5 and 3x + 3y + 3z – 8 = 0

Let π be the required plane. Let a, b, c be d.rs of normal to π.

Since π passes through (4, 4, 0) equation to π is a(x – 4) + b(y – 4) + c(z – 0) = 0

But π is perpendicular to x + 2y + 2z = 5 and 3x + 3y + 2z – 8 = 0

∴ \(\left.\begin{array}{r}

a+2 b+2 c=0 \\

3 a+3 b+2 c=0

\end{array}\right\}\).

∴ \(\frac{a}{-2}=\frac{b}{4}=\frac{c}{-3}\).

∴ Equation to π is -2(x – 4) + 4(y – 4)-3z = 0 [using(1)]

i.e., 2x – 4y + 3z + 8 = 0.

Solved Problems On Equations Of Planes And Orthogonal Projection

Example.5. Find the equation of the plane passing through (1, 0, -2) and perpendicular to the planes 2x + y – 2 = z; x – y – z = 3

Solution.

Given

(1, 0, -2)

2x + y – 2 = z; x – y – z = 3

Let π be the required plane. Let a, b, c be the drs. of the above plane.

The equation of the plane passing through (1, 0, -2) and having a, b, c as drs. is a(x-1) + b(y-0) + c(z+2) = 0 ⇒ a(x-1) + by + c(z+2) = 0 …..(1)

But the π plane is perpendicular to the planes 2x + y – z = 2 and x – y – z = 3.

∴ 2a + b – c = 0 …..(2), a – b – c = o …..(3)

Solving (2) and (3) \(\frac{a}{2}=\frac{b}{-1}=\frac{c}{3}\).

Equation of the π plane is 2(x-1)-y+3(z+2)=0 i.e., 2x – y + 3z + 4 = 0.

Example.6. Find the angles between the planes 2x – 3y – 6z = 6 and 6x + 3y – 2z = 18.

Solution.

Given Planes

2x – 3y – 6z = 6 and 6x + 3y – 2z = 18.

Let θ be one of the angles between the given planes.

∴ \(\theta=\cos ^{-1} \frac{2(6)-3(3)-6(-2)}{\sqrt{(4+9+36)} \sqrt{(36+9+4)}}=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{15}{49}\right)\)

The other angle between the planes is 180° – θ i.e., \(180^{\circ}-\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{15}{49}\right)\)

Example.7. Find the locus of the point whose distance from the origin is three times its distance from the plane 2x – y + 2z = 3.

Solution.

Given

2x – y + 2z = 3

Let O be the origin and P be the point (x1, y1, z1) such that OP is equal to 3 times its distance from the plane 2x – y + 2z = 3

∴ \(\mathrm{OP}^2=9 \cdot \frac{\left(2 x_1-y_1+2 z_1-3\right)^2}{4+1+4}\)

⇒ x12 + y12 + z12 = 4x12 + y12 + 4z12 + 9 – 4x1y1 – 4y1z1 + 8x1z1 – 12x1 + 6y1 – 12z1

⇒ 3x12 + 3z12 – 4x1y1 – 4y1z1 + 8x1z1 – 12x1 + 6y1 – 12z1 + 9 = 0

∴ Locus of P is 3x2 + 3z2 – 4xy – 4yz + 8xy – 12x + 6y – 12z + 9 = 0

Chapter 3 The Plane Systems Of Planes

Consider the equation ax + by + cz + d = 0, (a, b, c) ≠ (0, 0, 0),\(\lambda_1=\frac{b}{a}, \lambda_2=\frac{c}{a}, \lambda_3=\frac{d}{a}\) of a plane.

When three conditions satisfying the equation are given, λ1, λ2, λ3 can be uniquely determined and hence a plane can be uniquely determined.

When two conditions satisfying the equation are given, one of λ1, λ2, λ3 say, λ1 cannot be found uniquely and λ1 is called a parameter. Since λ1 can be assigned any real vaule, an infinite number of planes arise, and these planes are called a system of planes.

When one condition satisfying the equation is given we have two parameters, say, λ1, λ2 giving rise to a system of planes for different values of λ1, λ2.

We give below a few systems of planes involving one or two parameters.

(1) The equation ax + by + cz + λ = 0 represents the system of planes parallel to a given plane ax + by + cz + d = 0, λ being the parameter.

(2) The equation ax + by + cz + λ = 0 represents the system of planes perpendicular to lines with d.rs. a, b, c; λ being the parameter.

(3) The equation a(x – x1)+b(y – y1)+c(z – z1) = 0, (a, b, c) ≠ (0, 0, 0)

i.e., (x – x1) + λ1 (y – y1) + λ2 (z – z1)= 0 where a ≠ 0(say), λ1 = (b/a), λ2= (c/a) represents the system of planes passing through the point (x1, y1, z1); λ1, λ2 being the parameters.

(4) The equation λ1(a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 ) + λ2 (a2x + b2y + c2z + d2) = 0 represents the system of planes through the line of intersection of the planes a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0; λ1, λ2 being parameters and (λ1, λ2) ≠ (0, 0).

The truth of the statement can be seen from the theorem proved in the ensuing article.

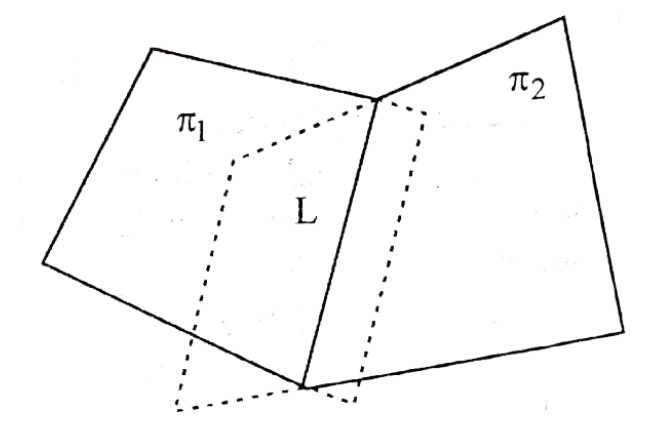

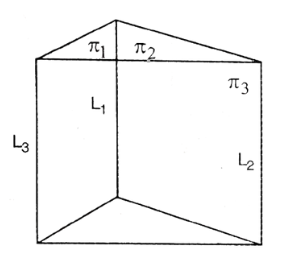

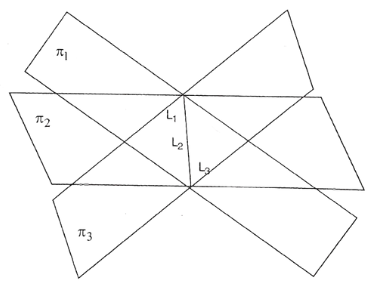

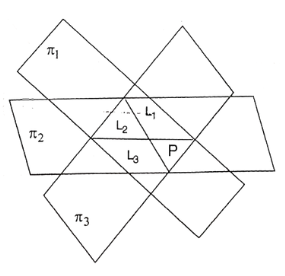

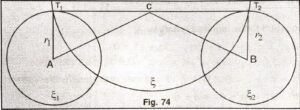

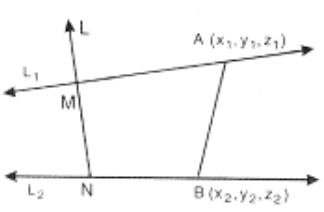

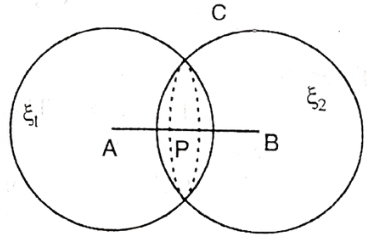

Theorem. π1 ≡ a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, π2≡ a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 represent two intersecting planes.

(A) If (λ1, λ2) ≠ (0, 0), then λ1π1 + λ2π2 = 0 represents a plane passing through the line L of the intersection of π1 and π2.

(B) Any plane passing through the line L of the intersection of π1 and π2 is given by λ1π1 + λ2π2 = 0, (λ1, λ2) ≠ (0, 0)

Proof: (A) Let S ≡ λ1π1 + λ2π2 = 0, (λ1, λ2) ≠ (0, 0)

S is a first-degree equation in x, y, z and hence represents a plane.

Now λ1 = 0 ⇒ S = π2, λ2 = 0 ⇒ S = π1. Let P(x1, y1, z1) ∈ L

∴ a1x1 + b1y1 + c1z1 + d1 = 0 …..(1) a2x1 + b2y1 + c2z1 + d2 = 0 …..(2)

Also from (1) and (2), P ∈ S, when (λ1, λ2) ≠ (0, 0)

∴ S represents a plane through the line L of the intersection of π1 and π2.

If λ1 ≠ 0, λ2 ≠ 0, for different values of λ1, λ2; S represents any plane through the line L of intersection π1 and π2 and different from π1 and π2.

(B) Let P(x1, y1, z1), Q(x2, y2, z2) be different points on L such that x1 ≠ x2 (say).

Let S ≡ αx + βy + γz + δ = 0 be a plane through L and hence

αx1 + βy1 + γz1 + δ = 0 …..(3) αx2 + βy2 + γz2 + δ = 0 …..(4)

Let l, m, n be d.rs. of L, the line of intersection of the planes π1 and π2.

∴ \(\left.\begin{array}{c}

a_1 l+b_1 m+c_1 n=0 \\

a_2 l+b_2 m+c_2 n=0

\end{array}\right\} \frac{l}{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}=\frac{m}{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}=\frac{n}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}\)

Since (b1c2 – b2c1, c1a2 – c2a1, a1b2 – a2b1) ≠ (0, 0, 0) without loss of generality we can take b1c2 – b2c1 ≠ 0.

For λ1, λ2 and (λ1, λ2) ≠ (0,0) there exist equations λ1b1 + λ2b2 = β, λ1c1 + λ2c2 = γ

such that they have a unique solution λ1 and λ2.

∴ αx + βy + γz + δ ≡ αx + (λ1b1 + λ2b2)y (λ1c1 + λ2c2)z + δ

≡ λ1(a1x + b1y + c1z + d1) + λ2(a2x + b2y + c2z + d2) + αx – λ1a1x – λ2a2x – λ1d1 – λ2d2 + δ

≡ λ1(a1x + b1y + c1z + d1) + λ2(a2x + b2y + c2z + d2) + (α – λ1a1– λ2a2) x + (δ – λ1d1 – λ2d2)

≡ λ1(a1x + b1y + c1z + d1) + λ2(a2x + b2y + c2z + d2) + λ3x + λ4 …..(5)

Where λ3 = α – λ1a1– λ2a2, λ4 = δ – λ1d1 – λ2d2

∴ P ∈ L ⇒ P ∈ S ⇒ αx1 + βy1 + γz1 + δ = 0 ⇒ λ3x1 + λ4= 0 …..(6)

using (3) and (5), and Q ∈ L ⇒ Q ∈ S ⇒ λ3x2 + λ4 = 0 …..(7)

using (4) and (5),

∴ (6) – (7) ⇒ λ3(x1 – x2) = 0 ⇒ λ3 = 0 (∵ x1 ≠ x2)

∴ From (6), λ4 = 0.

∴ S ≡ λ1π1 + λ2π2 = 0 is the plane passing through the line of intersection π1 and π2.

Note. Let λ1 ≠ 0 (say). Now equation to the plane (distinct from π1, π2) passing through the line of intersection of planes π1 and π2 can be taken as \(\pi_1+\left(\frac{\lambda_2}{\lambda_1}\right) \pi_2=0\) i.e. π1 + λπ2 = 0 where \(\lambda=\frac{\lambda_2}{\lambda_1}\). This form of equation might be taken while doing problems.

Chapter 3 The Plane Planes Bisecting The Angles Between Two Planes.

Theorem. π1 ≡ a1x + b1y + c1z + d1= 0, π2 ≡ a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 and d1d2 > 0. Equation to the plane bisecting the angle containing the origin between the planes

⇒ \(\pi_1, \pi_2 \text { is } \frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}}=+\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}}\)

and to the plane bisecting the other angle between the planes

⇒ \(\pi_1, \pi_2 \text { is } \frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}}=-\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}}\)

Proof: Equations to π1, π2 are

a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 …..(1) a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 …..(2) and d1 d2>0

we know that if p(x, y, z) is any point on one of the planes bisecting the angle between π1, π2 then the perpendicular distances of P from π1, π2 are equal (in magnitude) so that

⇒ \(\frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}}=\pm \frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}}\) are the equations to the bisecting planes.

∴ The equation to the plane bisecting the angle containing the origin is

⇒ \(\frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}}=+\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}} \text { if } d_1>0, d_2>0\) …..(7)

This plane bisects the angle containing the origin also bisects the vertically opposite angle.

∴ The equation to the plane bisecting the other angle and its vertically opposite angle is

⇒ \(\frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}}=-\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}} \text { if } d_1>0, d_2>0\) …..(8)

Note 1. In bisecting planes (7) and (8), one bisects the acute and the other bisects the obtuse angle between the given planes π1, π2.

The bisecting plane of the acute angle makes with either of the planes π1, π2 an angle less than 45° and the bisecting plane of the obtuse angle makes with either of the planes π1, π2 an angle greater than 45° (of course < 90°). This gives a test for determining which angle (acute or obtuse) each bisecting plane bisects.

2. Even if d1 < 0, d2 < 0, the theorem holds.

But if d1 > 0, d2 < 0 or d1 < 0, d2 > 0, equation to the plane bisecting the angle containing the origin is \(\frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}}=-\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}}\) and the other equation gives the other bisecting plane.

3. l1x + m1y + n1z = q1, l2x + m2y + n2z = q2 are two intersecting planes such that (l1, m1, n1), (l2, m2, n2) are unit points and q1q2 > 0 (q1 , q2 are of the same sign).

∴ The equation to the plane bisecting the angle containing the origin is (l1 – l2)x + (m1 – m2)y + (n1 – n2)z = q1 – q2 and the equation to the plane bisecting the other angle is (l1 + l2)x + (m1 + m2)y + (n1 + n2)z = q1 + q2

Chapter 3 The Plane Solved Problems

Example. 1. Find the equation to the plane through the point (x1, y1, z1) and parallel to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0

Solution.

Given point (x1, y1, z1) and plane ax + by + cz + d = 0

Let ax + by + cz + λ = 0 …..(1)

be the plane parallel to ax + by + cz + d = 0 …..(2)

for all values of λ.

If (1) passes through (x1, y1, z1) then ax1 + by1 + cz1 + λ = 0 i.e., λ = – ax1 – by1 – cz1

∴ Required plane is ax + by + cz – ax1 – by1 – cz1 = 0

i.e., a(x – x1) + b(y – y1) + c(z – z1) = 0

Example. 2. Find the equations of the planes through the intersection of the planes x + 3y + 6 = 0 and 3x – y – 4z = 0 such that the perpendicular distances of each from the origin are unity.

Solution.

Given planes x + 3y + 6 = 0 and 3x – y – 4z = 0

Let the plane passing through the intersection of the planes x + 3y + 6 = 0, 3x – y – 4z = 0 be (x + 3y + 6) + λ(3x – y – 4z) = 0

⇒ (1 + 3λ)x + (3 – λ)y – 4λz + 6 = 0 …..(1)

Perpendicular distance of origin from (1) = 1

⇒ \(\frac{6}{\sqrt{(1+3 \lambda)^2+(3-\lambda)^2+16 \lambda^2}}=1 \Rightarrow 26 \lambda^2=26 \Rightarrow \lambda=\pm 1\)

∴ Required planes are 4x + 2y – 4z + 6 = 0, -2x + 4y + 4z + 6 = 0

i.e., 2x + y – 2z + 3 = 0, x – 2y – 2z – 3 = 0

Example. 3. Find the equation to the plane through the intersection of the planes x + 2y + 3z + 4 = 0 and 4x + 3y + 3z + 1 = 0 and perpendicular to the plane x + y + z + 9 = 0

Solution.

Given planes x + 2y + 3z + 4 = 0 and 4x + 3y + 3z + 1 = 0 and perpendicular to the plane x + y + z + 9 = 0

Let the plane through the intersection of the planes

x + 2y + 3z + 4 = 0, 4x + 3y + 3z + 1 = 0 be (x + 2y + 3z + 4) + λ(4x + 3y + 3z + 1) = 0

⇒ (1 + 4λ)x + (2 + 3λ)y + (3 + 3λ)z + (4 + λ) = 0 …..(1)

If (1) is perpendicular to x + y + z + 9 = 0, then (1 + 4λ).1 + (2 + 3λ).1 + (3 + 3λ).1 = 0

i.e., 10λ = -6 i.e., λ = -3/5.

∴ Required plane is 7x – y – 6z – 17 = 0

Example. 4. Find the equation to the plane through the line of intersection of x – y + 3z + 5 = 0 and 2x + y – 2z + 6 = 0 and passing through (-3, 1,1)

Solution.

Given Planes x – y + 3z + 5 = 0 and 2x + y – 2z + 6 = 0 and passing through (-3, 1,1)

Let the equation to the plane through the intersection of the planes x – y + 3z + 5 = 0, be (x – y + 3z + 5) + λ(2x + y – 2z + 6) = 0 …..(1), for and λ.

Let (1) pass through the point (-3, 1,1).

∴ -3 – 1 + 3 + 5 + λ(-6 + 1 -2 + 6) = 0 i.e., -λ + 4 = 0 i.e., λ = 4

∴ Equation to the required plane is 9x + 3y – 5z + 29 = 0

Example. 5. Find the equation to the plane through (2, -3, ) and is normal to the line joining (3, 4, -1) and (2, -1, 5).

Solution.

Given

(2, -3, ) (3, 4, -1) and (2, -1, 5)

Let the plane through (2, -3, 1) and perpendicular to the join of p(3, 4, -1) and Q(2, -1, 5) be a(x – 2) + b(y + 3) + c(z – 1) = 0.

Since d.rs of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) are (3 – 2, 4 + 1, -1 -5) i.e., (1, 5, -6)

We have \(\frac{a}{1}=\frac{b}{5}=\frac{c}{-6}=\lambda, \text { say }\).

∴ Required plane is λ(x – 2) + 5λ(y + 3) – 6λ(z – 1) = 0

i.e., x – 2 + 5(y + 3) – 6(z – 1) = 0 i.e., x + 5y – 6z = -19

Example. 6. A variable plane passes through a fixed point (a, b, c). It meets the axes of reference in A, B, and C. Show that the locus of the point of intersection of the planes through A, B, C, and parallel to the coordinate planes is ax-1 + by-1 + cz-1 = 1

Solution.

Given

A variable plane passes through a fixed point (a, b, c). It meets the axes of reference in A, B, and C.

Let the variable plane meeting the coordinates axes in A, B,C be \(\frac{x}{\alpha}+\frac{y}{\beta}+\frac{z}{\gamma}=1\) …..(1)

∴ A = (α, 0, 0), B = (0, β, 0), C = (0, 0, γ)

Also (1) passes through the fixed point (a, b, c)

∴ \(\frac{a}{\alpha}+\frac{b}{\beta}+\frac{c}{\gamma}=1\)

But equations to the planes through A, B, C and parallel to the coordinate planes are x = α, y = β, z = γ.

Clearly they intersect at P = (α, β, γ)

∴ Locus of P from (2) is \(\frac{a}{x}+\frac{b}{y}+\frac{c}{z}=1 \text { i.e., } ax^{-1}+b y^{-1}+c z^{-1}=1\)

Example. 7. Find the bisecting plane of the acute angle between the planes 3x – 2y – 6z + 2 = 0, -2x + y – 2z – 2 = 0

Solution.

Equations to the given planes are taken as 3x – 2y – 6z + 2 = 0 …..(1)

2x – y + 2x + 2 = 0 …..(2)

(constant terms are taken as +ve)

∴ Equations to the bisecting planes between the given planes are

⇒ \(\frac{3 x-2 y+6 z+2}{\sqrt{(9+4+36)}}=\pm \frac{2 x-y+2 z+2}{\sqrt{(4+1+4)}}\)

i.e., 5x – y – 4z + 8 = 0 …..(3)

23x – 13y + 32z + 20 = 0 …..(4)

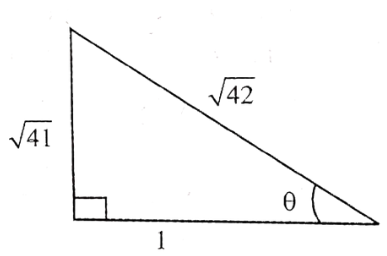

Let θ be the acute angle between (2) and (3)

∴ \(\cos \theta=\left|\frac{10+1-8}{\sqrt{9} \cdot \sqrt{(25+1+16)}}\right|=\frac{1}{(\sqrt{42})}\)

∴ \(\tan \theta=\sqrt{(41)}>1\)

Hence 2θ, the angle between the planes

(1) and (2) are greater than 90° i.e., obtuse.

∴ (3) is the equation to the plane bisecting the obtuse angle between (1) and (2).

∴ (4) is the equation to the plane bisecting the acute angle between (1) and (2).

Note. 5x – y – 4z + 8 = 0 is the plane bisecting the angle containing the origin between (1) and (2).

Chapter 3 The Plane Joint Equation Of A Pair Of Planes

Consider the pair of planes π1, π2 whose respective equations are

l1x + m1y + n1z + d1 = 0 …..(1) l2x + m2y + n2z + d2 = 0 …..(2)

Consider the equation (l1x + m1y + n1z + d1)(l2x + m2y + n2z + d2) = 0 …..(3)

Let P = (x1, y1, z1).

P ∈ π1 ⇒ l1x1 + m1y1 + n1z1 + d1 = θ ⇒ (l1x1 + m1y1 + n1z1 + d1)(l2x1 + m2y1 + n2z1 + d2) = 0

P ∈ π2 ⇒ l2x1 + m2y1 + n2z1 + d2 = θ ⇒ (l1x1 + m1y1 + n1z1 + d1)(l2x1 + m2y1 + n2z1 + d2) = 0

P lies on (3) ⇒ (l1x1 + m1y1 + n1z1 + d1)(l2x1 + m2y1 + n2z1 + d2) = 0

⇒ l1x1 + m1y1 + n1z1 + d1 = 0 or ⇒ l2x1 + m2y1 + n2z1 + d2 = 0 ⇒ P ∈ π1 or ⇒ P ∈ π2

∴ We have P ∈ π1 or P ∈ π2 : P lies on (3)

i.e., an equation is satisfied if and only if a point lies on the one plane or the other plane or both.

∴ (3) represents the joint or combined equation to the plane π1 and π2.

Note 1. a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 are two intersecting planes.

The combined equation to the pair of planes bisecting the angles between them is

⇒ \(\left[\frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)}}-\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)}}\right]\)

⇒ \(\left[\frac{a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1}{\sqrt{\left(a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2\right)}}+\frac{a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2}{\sqrt{\left(a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2\right)}}\right]=0\)

i.e., \(\frac{\left(a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1\right)^2}{a_1^2+b_1^2+c_1^2}-\frac{\left(a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2\right)^2}{a_2^2+b_2^2+c_2^2}=0\)

Theorem. S ≡ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy + 2ux + 2vy + 2wz + d = 0 represents a pair of planes π1, π2.

Then H ≡ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy = 0 represents a pair of planes through the origin and parallel to the planes π1, π2.

Proof. Let the planes π1, π2 represented by S = 0 be respectively l1x + m1y + n1z + d1 = 0, l2x + m2y + n2z + d2 = 0

∴ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy + 2ux + 2vy + 2wz + d

≡ (l1x + m1y + n1z + d1)(l2x + m2y + n2z + d2)

⇒ l1l2 = a,m1m2 = b,n1n2 = c, l1m2 + l2m1 = 2h, m1n2 + m2n1 = 2f, n1l2 + n2l1 = 2g.

Joint equation of the planes passing through the origin and parallel to π1, π2 is

(l1x + m1y + n1z)(l2x + m2y + n2z) = 0

i.e., l1l2x2 + m1m2y2 + n1n2z2 + (l1m2 + l2m1)xy + (m1n2 + m2n1)yz + (n1l2 + n2l1)zx = 0

i.e., ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy = 0 i.e., H = 0.

Definition. If H ≡ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy = 0 and D = \(\left|\begin{array}{lll}

a & h & g \\

h & b & f \\

g & f & c

\end{array}\right|\), then D is called the determinant of H.

Theorem. H ≡ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy = 0 represents the equation of a pair of planes or a plane if D = 0, f2 ≥ bc, g2 ≥ac, h2 ≥ ab.

Proof. H = 0 represents the equation to a pair of planes or a plane ⇒ H can be expressed as a product of two linear factors in x, y, z.

Let the factors be l1x + m1y + n1z + d1, l2x + m2y + n2z + d2

where (l1, m1, n1) ≠ (0, 0, 0)

∴ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy ≡ (l1x + m1y + n1z + d1)(l2x + m2y + n2z + d2)

⇒ l1l2 = a,m1m2 = b,n1n2 = c, l1m2 + l2m1 = 2h, m1n2 + m2n1 = 2f, n1l2 + n2l1 = 2g.

l1d2 + l2d1 = 0, m1d2 + m2d1 = 0, n1d2 + n2d1 = 0, d1d2 = 0

Now d1d2 = 0 ⇒ d1 = 0 or d2 = 0.

d2 = 0 ⇒ l2d1 = 0, m2d1 = 0, n2d1 = 0

⇒ d1 = 0 (∵ at least one of l2, m2, n2 is not equal to zero)

Similarly d1 = 0 ⇒ d2 = 0. ∴ d1 = d2 = 0

We know that \(\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

l_1 & l_2 & 0 \\

m_1 & m_2 & 0 \\

n_1 & n_2 & 0

\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

l_2 & m_2 & n_2 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right]\)

= \(\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

2 l_1 l_2 & l_1 m_2+l_2 m_1 & l_1 n_2+l_2 n_1 \\

l_2 m_1+l_1 m_2 & 2 m_1 m_2 & m_1 n_2+m_2 n_1 \\

n_1 l_2+l_1 n_2 & n_1 m_2+n_2 m_1 & 2 n_1 n_2

\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

2 a & 2 h & 2 g \\

2 h & 2 b & 2 f \\

2 g & 2 f & 2 c

\end{array}\right]\)

∴ \(\operatorname{det}\left\{\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

l_1 & l_2 & 0 \\

m_1 & m_2 & 0 \\

n_1 & n_2 & 0

\end{array}\right]\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

l_2 & m_2 & n_2 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right]\right\}=\operatorname{det}\left[\begin{array}{ccc}

2 a & 2 h & 2 g \\

2 h & 2 b & 2 f \\

2 g & 2 f & 2 c

\end{array}\right]\)

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

l_1 & l_2 & 0 \\

m_1 & m_2 & 0 \\

n_1 & n_2 & 0

\end{array}\right|\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

l_1 & m_2 & n_2 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

0 & 0 & 0

\end{array}\right|=8\left|\begin{array}{lll}

a & h & g \\

h & b & f \\

g & f & e

\end{array}\right| \Rightarrow 0 \times 0=8 \mathrm{D} \Rightarrow \mathrm{D}=0\).

Also, 4f2 – 4bc = (m1n2 + m2n1)2 – 4m1n2m2n1 = (m1n2 – m2n1)2 ≥ 0 ⇒ f2 ≥ bc.

Similarly, we can prove that g2 ≥ ac, h2 ≥ ab.

We give below two theorems, for which proofs may be supplied by the readers if needed.

1. H = 0 represents a pair of planes if (1) D = 0 and (2) at least one of h2 – ab, f2 – bc, g2 – ac is + ve and the remaining two are non-negative.

2. H = 0 represents a plane if D = 0, h2 – ab, f2 – bc, g2 – ac. In this case, H takes the form (a1x + b1y + c1z)2.

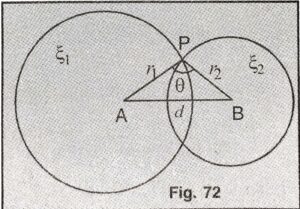

Theorem. If θ(≤ π/2) is the angle between the pair of planes H = 0, then \(\cos \theta=\left|\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt{\left\{(a+b+c)^2+4\left(f^2+g^2+h^2-a b-b c-c a\right)\right\}}}\right|\)

Proof. Let the pair of planes represented by H = 0 be

l1x + m1y + n1z = 0, l2x + m2y + n2z = 0.

∴ ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy ≡ (l1x + m1y + n1z)(l2x + m2y + n2z)

⇒ l1l2 = a, m1m2 = b, n1n2 = c

l1m2 + l2m1 – 2h, m1n2 + m2n1 = 2f, n1l2 + n2l1 = 2g

Since θ(≤ (π/2)) is the angle between the planes,

⇒ \(\cos \theta=\mid \frac{l_1 l_2+m_1}{\sqrt{\left(l_1^2+m_1^2+n_1^2\right)}}\frac{m_2+n_1 n_2}{\sqrt{\left(l_2^2+m_2^2+n_2^2\right)}}|\)

=\(\left|\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt{\left\{\left(a^2+b^2+c^2+4 h^2-2 a b+4 f^2-2 b c+4 g^2-2 a c\right)\right\}}}\right|\)

=\(\left|\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt{\left\{(a+b+c)^2+4\left(f^2+g^2+h^2-b c-c a-a b\right)\right\}}}\right|\)

Cor. 1. Planes are perpendicular <=> θ = 90°

<=> cosθ = 0 <=> a + b + c = 0

<=> Coefficient of x2 + Coefficient of y2 + Coefficient of z2 = 0

2. Planes are identical (coincident) <=> θ = 0°

<=> \(\cos \theta=1 \Leftrightarrow\left|\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt{\left\{(a+b+c)^2+4\left(f^2+g^2+h^2-a b-b c-c a\right)\right\}}}\right|=1\)

<=> (a + b + c)2 = (a + b + c)2 + 4(f2 +g2 + h2 – ab – bc – ca)

<=> f2 + g2 + h2 – bc – ca – ab = 0 <=> (f2 – bc) + (g2 – ac) + (h2 – ab) = 0

<=> f2 = bc, g2 = ac, h2 = ab (∵ f2 ≥ bc, g2 ≥ ac, h2 ≥ ab)

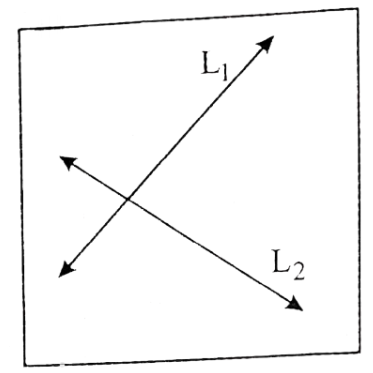

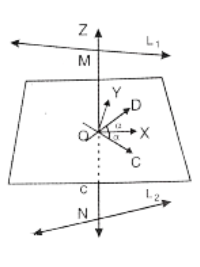

Note. 1. l1x + m1y + n1z = 0, l2x + m2y + n2z = 0 are two planes intersecting in a line with d.rs., l, m, n.

⇒ l1l + m1m + n1n = 0, l2l + m2m + n2n = 0 ⇒ \(\frac{l}{m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1}=\frac{m}{n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1}=\frac{n}{l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1}\)

⇒ \(\frac{l}{\left[\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1\right)^2-4 m_1 n_2 n_1 m_2\right]}=\frac{m}{\sqrt{\left[\left(n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1\right)^2-4 n_1 l_2 n_2 l_1\right]}}=\frac{n}{\sqrt{\left[\left(l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1\right)^2-4 l_1 m_2 l_2 m_1\right]}}\)

⇒\(\frac{l}{\sqrt{\left(4 f^2-4 b c\right)}}=\frac{m}{\left(\sqrt{\left.4 g^2-4 a c\right)}\right.}=\frac{n}{\sqrt{\left(4 h^2-4 a b\right)}}\frac{l}{\overline{\left(f^2-b c\right)}}=\frac{m}{\left(\sqrt{\left.g^2-a c\right)}\right.}=\frac{n}{\sqrt{\left(h^2-a b\right)}}\)

⇒ d.rs. of the common line are \(\sqrt{\left(f^2-b c\right)}, \sqrt{\left(g^2-a c\right)}, \sqrt{\left(h^2-a b\right)}\)

2. If θ(≤ π/2) is the angle between the pair of intersecting planes given by ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy + 2ux + 2vy + 2wz + d = 0, then

⇒ \(\cos \theta=\left|\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt{\left\{(a+b+c)^2+4\left(f^2+g^2+h^2-a b-b c-c a\right)\right\}}}\right|\).

d.rs. of the line of intersection are \(\sqrt{\left(f^2-b c\right)}, \sqrt{\left(g^2-a c\right)}, \sqrt{\left(h^2-a b\right)}\)

Chapter 3 The Plane Solved Problems

Example. 1. Prove that the equation 2x2 – 6y2 – 12z2 + 18yz + 2zx + xy = 0 represents a pair of planes, and find the angle between them.

Solution.

Let the given equation be ax2 + by2 + cz2 + 2fyz + 2gzx + 2hxy = 0 …..(1)

comparing the given equation to (1), a =2, b = -6, c = -12, f = 9, g = 1, h = 1/2

∴ \(\mathrm{D}=\left|\begin{array}{lll}

a & h & g \\

h & b & f \\

g & f & c

\end{array}\right|=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

2 & 1 / 2 & 1 \\

1 / 2 & -6 & 9 \\

1 & 9 & -12

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(2(72-81)-\frac{1}{2}(-6-9)+1\left(\frac{9}{2}+6\right)=-18+\frac{15}{2}+\frac{21}{2}=0\)

f2 = 81, bc = 72 ⇒ f2 > bc, ac = -24 ⇒ g2 > ac, h2 = 1/4, ab = -12 ⇒ h2 > ab.

∴ The given equation represents a pair of planes through the origin.

Let θ be the acute angle between the planes.

∴ \(\cos \theta=\left|\frac{a+b+c}{\sqrt{\left[(a+b+c)^2+4\left(f^2+g^2+h^2-a b-b c-c a\right)\right]}}\right|\)

OR : 2x2 – 6y2 – 12z2 + 18yz + 2zx + xy = 0

⇒ 2x2 + x(y + 2z) – (6y2 + 12z2 – 18yz) = 0

⇒ \(x=\frac{-(y+2 z) \pm \sqrt{\left[(y+2 z)^2+8\left(6 y^2+12 z^2-18 y z\right)\right]}}{4}\)

⇒ \(4 x=-(y+2 z) \pm \sqrt{\left(49 y^2-140 y z+100 z^2\right)} \Rightarrow 4 x=-y-2 z \pm(7 y-10 z)\)

⇒ 4x – 6y + 12z = 0, 4x + 8y – 8z = 0 ⇒ 2x – 3y + 6z = 0, x + 2y – 2z = 0

∴ The given equation represents a pair of planes through the origin.

⇒ \(\cos \theta=\frac{2(1)-3(2)+6(-2)}{\sqrt{(4+9+36)} \cdot \sqrt{(1+4+4)}}=\frac{+16}{21}\) ∴ \(\theta=\cos ^{-1}\left(\frac{16}{21}\right)\)

Example. 2. If a2 + b2 + c2 > 2ab + 2bc + 2ca, show that the equation ax2 + by2 + cz2 -(a + b – c)xy – (b + c – a)yz – (c + a – b)zx = 0 represents a pair of planes. Also show that the line of intersection of the planes makes equal angles with the coordinate axes.

Solution.

Given

a2 + b2 + c2 > 2ab + 2bc + 2ca,

Let H ≡ ax2 + by2 + cz2 -(a + b – c)xy – (b + c – a)yz – (c + a – b)zx = 0 ……(1)

∴ Determinant of H = D

=\(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

a & \frac{-(a+b-c)}{2} & \frac{-(c+a-b)}{2} \\

\frac{-(a+b-c)}{2} & b & \frac{-(b+c-a)}{2} \\

\frac{-(c+a-b)}{2} & \frac{-(b+c-a)}{2} & c

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(-\frac{1}{8}\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

2 a & (a+b-c) & (c+a-b) \\

(a+b-c) & -2 b & (b+c-a) \\

(c+a-b) & (b+c-a) & -2 c

\end{array}\right| R_1=R_1+R_2+R_3\).

= \(-\frac{1}{8}\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

0 & 0 & 0 \\

a+b-c & -2 b & b+c-a \\

c+a-b & b+c-a & -2 c

\end{array}\right|=0\)

[f2 > bc be condition]:

⇒ \(\left(\frac{b+c-a}{2}\right)^2-b c=\frac{a^2+b^2+c^2-(2 a b+2 b c+2 c a)}{4}>0 \text { (by hyp.) }\)

Similarly [g2 > ac, h2 ≥ ab conditions] \(\left(\frac{c+a-b}{2}\right)^2-a c>0,\left(\frac{a+b-c}{2}\right)^2-a b>0\)

∴ (1) represents a pair of intersecting planes.

For the common line \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) of intersection of the planes, d.rs. are

⇒ \(\sqrt{\left[\left(\frac{b+c-a}{2}\right)^2-b c\right]}, \sqrt{\left[\left(\frac{c+a-b}{2}\right)^2-c a\right]}, \sqrt{\left[\left(\frac{a+b-c}{2}\right)^2-a b\right]}\)

i.e. \(\frac{\sum a^2-2 a b}{4}, \frac{\sum a^2-2 a b}{4}, \frac{\sum a^2-a b}{4}\)

But d.cs. of \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OX}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OY}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OZ}} \text { are } 1,0,0 ; 0,1,0 ; 0,0,1\).

Let \(\theta=\left(\begin{array}{ll}

\overrightarrow{P Q} & \overrightarrow{O X}

\end{array}\right)\)

∴ \(\cos \theta=\frac{1.1+1.0+1.0}{\sqrt{3} \sqrt{1}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \text { i.e. } \theta=\cos ^{-1} \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\)

Similarly we can observe that \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PO}} \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OY}}=\operatorname{Cos}^{-1}(1 / \sqrt{3}),(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}} \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OZ}})=(1 / \sqrt{3})\)

∴ The common line \(\overleftrightarrow{P Q}\) makes equal with the axes.

Example.3. Show that the equation x2 + 4y2 + 9z2– 12yz – 6zx + 4xy + 5x + 10y – 15z + 6 = 0 represents a pair of parallel planes and find the distance between them.

Solution.

Given

x2 + 4y2 + 9z2 – 12yz – 6zx + 4xy = (x + 2y – 3z)2

∴ x2 + 4y2 + 9z2 – 12yz – 6zx + 4xy + 5x + 10y – 15z + 6

≡ (x + 2y – 3z + k)(x + 2y – 3z – l) where

k + l = 5, 2k + 2l = 10, – 3k – 3l = -15, kl = 6 i.e., k = 3, l = 2

∴ The given equation represents the planes

x + 2y – 3z + 3 = 0, x + 2y – 3z + 2 = 0 which are parallel.

∴ Distance between the parallel planes =\(\frac{|3-2|}{\sqrt{(1+4+9)}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{(14)}}\)