Vector Differentiation- 3 Exercise 3 Solved Problems

1. Define a vector function.

Vector function: Let S⊆ R . If to each t ∈ S there corresponds a unique vector f(t) then the corresponding f is called a vector function with scalar variable t of domain S.

2. Define the limit of a vector function.

Limit: Let f be a vector function over the domain S and an as be a limit point of S. A vector L is said to be the limit of at an if to each given ε>0,∃δ>0∋t ∈ S, 0<|t-a| δ ⇒|f(t)-L|<ε It is denoted by\(\underset{t \rightarrow a}{L t}\)f(t) = L.

3. Define the continuity of a vector function.

- Continuous at a point: let f be a vector function with domain S and a ∈ S. Then f is said to be continuous at if\(\underset{t \rightarrow a}{L t}\)f(t)=f(a)

- Continuity on a set: let f be a vector function with domain S. Then f is said to be continuous on S if f is continuous at a for all a ∈ S.

4. Define the derivative of a vector function.

Derivative: Let f be a vector function with domain S and a ∈ Then f is said to be differentiable at an if \(\underset{t \rightarrow a}{L t}\)\(\frac{f(t)-f(a)}{t-a}\)exits. At the limit is called the derivative of f at a. It is denoted by f'(a) or \(\left(\frac{d f}{d t}\right)_{t=a}\)

Calculus Vector Differentiation Exercise Solutions

5. If f, g are two differentiable vector functions at t then prove that f + g is differentiable at t and\(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f}+\mathbf{g}\}\)=\(=\frac{d f}{d t}+\frac{d g}{d t}\)

Solution:

Given

f, g are two differentiable vector functions at t

⇒ \(\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{(\mathbf{f}+\mathbf{g})(t+h)-(\mathbf{f}+\mathbf{g})(t)}{h}=\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t+h)+\mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)-\mathbf{g}(t)}{h}\)

= \(\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)}{h}+\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{g}(t)}{h}=\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}+\frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{f}+\mathbf{g}\)are differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f}+\mathbf{g}\}=\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}+\frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\)

6. If f and g are two differentiable vector functions at t then prove that

- f • g is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{g}\}\)=\(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \cdot \mathbf{g}+\mathbf{f} \cdot \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\)

- f x g is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}\}\)=\(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times \mathbf{g}+\mathbf{f} \times \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\)

Solution:

1. \(\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{(\mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{g})(t+h)-(\mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{g})(t)}{h}=\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{1}(t+h) \cdot \mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t) \cdot \mathbf{g}(t)}{h}\)

= \(\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t \cdot+h) \cdot \mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t+h) \cdot \mathbf{g}(t)+\mathbf{f}(t+h) \cdot \mathbf{g}(t)-\mathbf{f}(t) \cdot \mathbf{g}(t)}{h}\)

= \(\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t}\left\{\mathbf{f}(t+h) \cdot \frac{[\mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{g}(t)]}{h}+\frac{[\mathbf{f}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)]}{h} \cdot \mathbf{g}(t)\right\}\)

= \(\left[{ }_{h \rightarrow 0}^{L t} \mathbf{f}(t+h)\right] \cdot\left[{ }_{h \rightarrow 0}^{L t} \frac{\mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{g}(t)}{h}\right]+\left[{ }_{h \rightarrow 0}^{L t} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)}{h}\right] \cdot \mathbf{g}(t)\)

= \(\mathbf{f} \cdot \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}+\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \cdot \mathbf{g}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{g}\) is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f} \cdot \mathbf{g}\}=\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \cdot \mathbf{g}+\mathbf{f} \cdot \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\)

2. \(\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g})(t+h)-(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g})(t)}{h}=\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t+h) \times \mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t) \times \mathbf{g}(t)}{h}\)

= \(\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t+h) \times \mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t+h) \times \mathbf{g}(t)+\mathbf{f}(t+h) \times \mathbf{g}(t)-\mathbf{f}(t) \times \mathbf{g}(t)}{h .}\)

= \(\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0}\left\{\mathbf{f}(t+h) \times \frac{[\mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{g}(t)]}{h}+\frac{[\mathbf{f}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)]}{h} \times \mathbf{g}(t)\right\}\)

= \([\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \mathbf{f}(t+h)] \times\left[\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{g}(t+h)-\mathbf{g}(t)}{h}\right]+\left[\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\mathbf{f}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)}{h}\right] \times \mathbf{g}(t)\)

= \(\mathbf{f} \times \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}+\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times \mathbf{g}\) .

∴ \(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}\) is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}\}=\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times \mathbf{g}+\mathbf{f} \times \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\)

Ordinary Derivatives Of Vector Functions Explained

7. If f, g, h are three differentiable vector functions at t then prove that

1. f×(g×h) is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f} \times(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h})\}\)=\(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h})+\mathbf{f} \times\left(\frac{d \boldsymbol{g}}{d t} \times \mathbf{h}\right)+\mathbf{f} \times\left(\mathbf{g} \times \frac{d \mathbf{h}}{d t}\right)\)

2. (f×g)×h is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\{(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}) \times \mathbf{h}\}\)=\(\left(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times \mathbf{g}\right) \times \mathbf{h}+\left(\mathbf{f} \times \frac{d \boldsymbol{g}}{d t}\right) \times \mathbf{h}+(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}) \times \frac{d \mathbf{h}}{d t}\)

Solution:

1. g,h is differentiable at t ⇒ g × h is differentiable at t

f,g × h are differentiable at t ⇒ f×(g × h) is differentiable at t

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d t}\{\mathbf{f} \times(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h})\}\)

= \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h}), \mathbf{f} \times \frac{d}{d t}(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h})\)

= \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h})+\mathbf{f} \times\left(\frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t} \times \mathbf{h}+\mathbf{g} \times \frac{d \mathbf{h}}{d t}\right)\)

= \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times(\mathbf{g} \times \mathbf{h})+\mathbf{f} \times\left(\frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t} \times \mathbf{h}\right)+\mathbf{f} \times\left(\mathbf{g} \times \frac{d \mathbf{h}}{d t}\right)\)

2. f, g is differentiable at t ⇒ (f×g) is differentiable at t

f×g,h are differentiable at t ⇒ (f×g) ×h is differentiable at t

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d t}\{(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}) \times \mathbf{h}\}=\left(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times \mathbf{g}+\mathbf{f} \times \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\right) \times \mathbf{h}+(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}) \times \frac{d \mathbf{h}}{d t}\)

= \(\left(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t} \times \mathbf{g}\right) \times \mathbf{h}+\left(\mathbf{f} \times \frac{d \mathbf{g}}{d t}\right) \times \mathbf{h}+(\mathbf{f} \times \mathbf{g}) \times \frac{d \mathbf{h}}{d t}\)

8. If f is a differentiable vector function at t and φ is a differentiable scalar function at t then prove that φ f is differentiable at t and\(\frac{d}{d t}\{\varphi \boldsymbol{f}\}\)=\(\varphi \frac{d f}{d t}+\frac{d \varphi}{d t} \mathbf{f}\)

Solution:

Given

f is a differentiable vector function at t and φ is a differentiable scalar function at t

⇒ \(\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{(\varphi \mathbf{f})(t+h)-(\varphi t)(t)}{h}=\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{\varphi(t+h) \mathbf{f}(t+h)-\varphi(t) \mathbf{f}(t)}{h}\)

= \(\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0} \frac{\varphi(t+h) \mathbf{f}(t+h)-\varphi(t+h) \mathbf{f}(t)+\varphi(t+h) \mathbf{f}(t)-\varphi(t) \mathbf{f}(t)}{h}\)

= \(\text{Lt}_{h \rightarrow 0}\left\{\varphi(t+h) \frac{[\mathbf{f}(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)]}{h}+\frac{[\varphi(t+h)-\varphi(t)]}{h}(t)\right\}\)

= \(\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \varphi(t+h) \underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{f(t+h)-\mathbf{f}(t)}{h}+\underset{h \rightarrow 0}{L t} \frac{\varphi(t+h)-\varphi(t)}{h} \mathbf{f}(t)=\varphi(t) \frac{d \mathbf{t}}{d t}+\frac{d \varphi}{d t} \mathbf{f}\)

∴ φ is differentiable at t and \(\frac{d}{d t}\){φf}= φ \(\frac{d t}{dt}+\frac{d \varphi}{d t}\) f

Vector Differentiation Practice Problems With Solutions

9. Prove that a vector function f is constant if f \(\frac{d f}{d t}\)=0

Solution:

Suppose f is constant then \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\)=0

Conversely suppose that \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\)=0 .Let f= f1i+f2j+f3k

⇒ \(\frac{d f_1}{d t} \mathbf{i}+\frac{d f_2}{d t} \mathbf{j}+\frac{d f_3}{d t} \mathbf{k}\)=0

⇒ \(\frac{d f_1}{d t}\)=0, \(\frac{d f_2}{d t}\)=0,\(\frac{d f_3}{d t}\)=0

⇒ f1,f2,f3 are constants ⇒ f is a constant vector function.

10. Prove that a vector function f is o fconstant magnitude if f.\(\frac{d f}{d t}\)=0

Solution:

Suppose f is constant magnitude. Then f2=|f|2= a constant.

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}\){f2}=0 ⇒ 2f. \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\) =0 ⇒ f. \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\)

Conversely suppose that f. \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\) =0⇒ 2f. \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\) =0 ⇒ \(\frac{d}{d t}\){f2}=0

∴ f2 is constant ⇒|f|2= constant ⇒ f is of constant length.

11. Prove that a vector function I has constant direction if f x \(\frac{d f}{d t}\)=0

Solution:

Let f (t)=f (t)F where f (t) =| f (t)| and F (t) is a vector function with unit magnitude, for every t in the domain of f.

∴ \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\) = \(\frac{d}{d t}\){fF} =f\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}+\frac{d f}{d t}\) F

f× \(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\)=f F ×(f\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}+\frac{d f}{d t}\) F)= f2( F ×\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\)) +f\(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\)

(F×F) = f(F×\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\))

Suppose f has a constant direction.

Then F is constant ⇒ \(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\))=0

⇒ F× \(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\)=0 ⇒ f×\(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\)= f2( F ×\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\)) =0

Conversely suppose that f×\(\frac{d \mathbf{f}}{d t}\) = 0. Then f2( F ×\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\)) =0⇒ F ×\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\)=0

F is of unit length ⇒ F.\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\) = 0

F ×\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\)=0 ⇒ F.\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\) = 0 ⇒\(\frac{d \mathbf{F}}{d t}\) = 0 ⇒F is constant ⇒ f have constant direction.

12. If r = e-ti + log(t2+ l)J-tan t k then find \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}\),\(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\), \(\left|\frac{d t}{d t}\right|\), and \(\left|\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right|\) at =0

Solution:

Given

r = e-ti + log(t2+ l)J-tan t k

r = \(e^{-t} \mathbf{i}+\log \left(t^2+1\right) \mathbf{J}-\tan t \mathbf{k} \Rightarrow \frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-e^{-t} \mathbf{i}+\frac{2 t}{t^2+1} \mathbf{J}-\sec ^2 t \mathbf{k} \)

⇒ \(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=e^{-t} \mathbf{I}+\frac{\left(t^2+1\right) 2-2 t \cdot 2 t}{\left(t^2+1\right)^2} \mathbf{J}-2 \sec ^2 t \tan t \mathbf{k}\)

At t = 0, \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-\mathbf{I}-\mathbf{k}, \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=\mathbf{I}+2 \mathbf{J},\left|\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}\right|=\sqrt{1+1}=\sqrt{2},\left|\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right|=\sqrt{1+4}=\sqrt{5}\)

13. If r = t2 i- tj + (2t+ 1) k, find the values of \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}\),\(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\), \(\left|\frac{d r}{d t}\right|\), and \(\left|\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right|\) at =0

Solution:

Given

r = t2 i- tj + (2t+ 1) k

r = \(t^2 \mathbf{I}-t \mathbf{j}+(2 t-1) \mathbf{k} \Rightarrow \frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=2 t \mathbf{I}-\mathbf{J}+2 \mathbf{k}, \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d \mathbf{t}^2}=2 \mathbf{r} . \)

At t = 0, \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-\mathbf{J}+2 \mathbf{k}, \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=2 \mathbf{i},\left|\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}\right|=\sqrt{1+4}=\sqrt{5},\left|\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right|=2\)

14. If r = e-ti + + log(t2+ l)J-tan t k find\(\left(\frac{d r}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 r}{d t^2}\right)\) at t=0

Solution:

Given

r = e-ti + + log(t2+ l)J-tan t k

r = \(e^{-t} \mathbf{i}+\log \left(t^2+1\right) \mathbf{j}-\tan t \mathbf{k} \Rightarrow \frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-e^{-t} \mathbf{i}+\frac{2 t}{t^2+1} \mathbf{j}-\sec ^2 t \mathbf{k}\)

and \(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=e^{-t} \mathbf{i}+\frac{\left(t^2+1\right) 2-2 t \cdot 2 t}{\left(t^2+1\right)^2} \mathbf{j}-2 \sec ^2 t \tan t \mathbf{k}\)

At t=0, \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-\mathbf{i}-\mathbf{k}, \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}\)

⇒ \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=\left|\begin{array}{rrr}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

-1 & 0 & -1 \\

1 & 2 & 0

\end{array}\right|\)= \(\mathbf{i}(0+2)-\mathbf{j}(0+1)+\mathbf{k}(-2-0)=2 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}-2 \mathbf{k}\)

Vector Differentiation Practice Problems With Solutions

15. If r=et ( c cos 2t +d sin 2t) where c and d are constant vectors then show that \(\frac{d^2 r}{d t^2}-2 \frac{d r}{d t}+5 r\)=0

Solution:

Given that \(\mathbf{r}=e^t(\mathbf{c} \cos 2 t+\mathbf{d} \sin 2 t)\)

⇒ \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=e^t(-2 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+2 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t)+e^t(\mathbf{c} \cos 2 t+\mathbf{d} \sin 2 t)\)

= \(e^t(-2 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+2 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t+\mathbf{c} \cos 2 t+\mathbf{d} \sin 2 t)\)

⇒ \(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=e^t(-4 \mathbf{c} \cos 2 t-4 \mathbf{d} \sin 2 t-2 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+2 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t)\)

+ \(e^t(-2 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+2 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t+\mathbf{c} \cos 2 t+\mathbf{d} \sin 2 t)\)

= \(e^t(-3 c \cos 2 t-3 \mathbf{d} \sin 2 t-4 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+4 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t)\)

⇒ \(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}-2 \frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}+5 \mathbf{r}=e^t(-3 \mathbf{c} \cos 2 t-3 \mathbf{d} \sin 2 t-4 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+4 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t)\)

-2 \(e^t(-2 \mathrm{e} \sin 2 t+2 \mathrm{~d} \cos 2 t+\mathrm{c} \cos 2 t+\mathrm{d} \sin 2 t)+5 e^t(\mathrm{c} \cos 2 t+\mathrm{d} \sin 2 t)\)

= \(e^t(-3 \mathbf{c} \cos 2 t-3 \mathbf{d} \sin 2 t-4 \mathbf{c} \sin 2 t+4 \mathbf{d} \cos 2 t+4 \mathbf{c} \sin 2t\)

-4 \(\mathbf{d} \cos 2 t-2 c \cos 2 t-2 \mathbf{d} \sin 2 t+5 \mathbf{c o s} 2 t+5 \mathbf{d} \sin 2 t)=\mathbf{0} \text {. }\)

16. If A= t i-t2j+(2t=1) k and B = (2t-3)i+j-tk, find

- (A×B)’

- (|A+B|)’ at t=1.

Solution:

1. \(\mathbf{A} \times \mathbf{B}=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

t^2 & -t & 2 t+1 \\

2 t-3 & 1 & -t

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(t^2-2 t-1\right)-\mathbf{j}\left(-t^3-4 t^2+4 t+3\right)+\mathbf{k}\left(t^2+2 t^2-3 t\right)\)

= \(\left(t^2-2 t-1\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(t^3+4 t^2-4 t-3\right) \mathbf{j}+\left(3 t^2-3 t\right) \mathbf{k}\)

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}(\mathbf{A} \times \mathbf{B})=(2 t-2) \mathbf{i}+\left(3 t^2+8 t-4\right) \mathbf{j}+(6 t-3) \mathbf{k}=7 \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k}\) at t=1 .

2. A+B = \(\left[t^2 \mathbf{i}-t \mathbf{j}+(2 t+1) \mathbf{k}\right]+[(2 t-3) \mathbf{i}+\mathbf{j}-t \mathbf{k}]\)

= \(\left(t^2+2 t-3\right) \mathbf{i}+(1-t) \mathbf{j}+(t+1) \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(|\mathbf{A}+\mathrm{B}|=\sqrt{\left(t^2+2 t-3\right)^2+(1-t)^2+(t+1)^2}\)

= \(\sqrt{t^4+4 t^2+9+4 t^3-6 t^2-12 t+2+2 t^2}\)

= \(\sqrt{t^4+4 t^3-12 t+11}\)

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d t}(|\mathbf{A}+\mathrm{B}|)=\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{t^4+4 t^3-12 t+11}} \times 4 t^3+12 t^2-12=\frac{4+12-12}{2 \sqrt{1+4-12+11}}=\frac{2}{2}\)

=1 at t=1 .

17. If A= 5t2i+tj-t k and B = sin ti- cost j then find

(1) \(\frac{d}{d t}\) (A.B)

(2) \(\frac{d}{d t}\) (AB)

(3) \(\frac{d}{d t}\) (A.A)

Solution:

(1) A.B = 5t2 sint-t cos t

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}\) ( A.B) 5t2 cos t +10 t sin t+ t sin t -cos t =5t2 cos t + 11 t sin t -cos t

(2) \(\mathbf{A} \times \mathbf{B}\)

= \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

5 t^2 & t & -t^3 \\

\sin t & -\cos t & 0

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(0-t^3 \cos t\right)-\mathbf{j}\left(0+t^3 \sin t\right)+\mathbf{k}\left(-5 t^2 \cos t-t \sin t\right)\)

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}(\mathbf{A} \times \mathbf{B})=\left(t^3 \sin t-3 t^2 \cos t\right) \mathbf{i}-\left(t^3 \cos t+3 t^2 \sin t\right) \mathbf{J}\)

+ \(\left(5 t^2 \sin t-10 t \cos t-t \cos t-\sin t\right) \mathbf{k}\)

(3) \(\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{A}=\left(5 t^2\right)^2+(t)^2+\left(-t^3\right)^2=25 t^4+t^2+t^6=t^6+25 t^4+t^2\)

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}(\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{A})=\frac{d}{d t}\left(t^6+25 t^4+t^2\right)=6 t^5+100 t^3+2 t \text {. }\)

18. If r= a cos t i+ a sin t j+ at tan θ k then find \(\left|\frac{d r}{d t} \times \frac{d^2}{d t^2}\right|\) and \(\left[\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2} \frac{d^3 \mathbf{r}}{d t^3}\right]\)

Solution: r- a cos t i+ a sin t j+ at tan θ k

r = \(a \cos t \mathbf{i}+a \sin t \mathbf{j}+a t \tan \theta \mathbf{k}\)

∴ \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-a \sin t \mathbf{i}+a \cos t \mathbf{j}+a \tan \theta \mathbf{k}\), \(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=-a \cos t \mathbf{i}-a \sin t \mathbf{j}\), \(\frac{d^3 \mathbf{r}}{d t^3}=a \sin t \mathbf{i}-a \cos t \mathbf{j}\)

∴ \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\)

= \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

-a \sin t & a \cos t & a \tan \theta \\

-a \cos t & -a \sin t & 0

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(0+a^2 \sin t \tan \theta\right)-\mathbf{j}\left(0+a^2 \cos t \tan \theta\right)+\mathbf{k}\left(a^2 \sin ^2 t+a^2 \cos ^2 t\right)\)

= \(a^2 \sin t \tan \theta \mathbf{i}-a^2 \cos t \tan \theta \mathbf{j}+a^2 \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\left|\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right|\)

= \(\sqrt{a^4 \sin ^2 t \tan ^2 \theta+a^4 \cos ^2 t \tan ^2 \theta+a^4}=a^2 \sqrt{\tan ^2 \theta+1}=a^2 \sec \theta\)

⇒ \({\left[\begin{array}{lll}

\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} & \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2} & \frac{d^3 \mathbf{r}}{d t^3}

\end{array}\right]}\)

= \({\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

-a \sin t & a \cos t & a \tan \theta \\

-a \cos t & -a \sin t & 0 \\

a \sin t & -a \cos t & 0

\end{array}\right|}\)

= \(a \tan \theta\left(a^2 \cos ^2 t+a^2 \sin ^2 t\right)=a^3 \tan \theta\)

19. If r= a cos t i+ a sin t j+ at tan θ k , find \(\left(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right)\) at t=0.

Solution: r= a cos t i+ a sin t j+ at tan θ k

r = \(a \cos t \mathbf{I}+a \sin t \mathbf{j}+a t \tan \theta \mathbf{k}\)

∴ \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t}=-a \sin t \mathbf{i}+a \cos t \mathbf{j}+a \tan \theta \mathbf{k}\), \(\frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}=-a \cos t \mathbf{i}-a \sin t \mathbf{j}\), \(\frac{d^3 \mathbf{r}}{d t^3}=a \sin t \mathbf{i}-a \cos t \mathbf{j}\)

∴ \(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\)

= \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

-a \sin t & a \cos t & a \tan \theta \\

-a \cos t & -a \sin t & 0

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{I}\left(0+a^2 \sin t \tan \theta\right)-\mathbf{J}\left(0+a^2 \cos t \tan \theta\right)+\mathbf{k}\left(a^2 \sin ^2 t+a^2 \cos ^2 t\right)\)

= \(a^2 \sin t \tan \theta \mathbf{i}-a^2 \cos t \tan \theta \mathbf{j}+a^2 \mathbf{k}\)

∴ \(\left(\frac{d \mathbf{r}}{d t} \times \frac{d^2 \mathbf{r}}{d t^2}\right)_{t=0}=-a^2 \tan \theta \mathbf{J}+a^2 \mathbf{k}\)

Step-By-Step Guide To Ordinary Vector Derivatives In Calculus

20. If A= sint i+ cos t j+tk, B= cos t i-sin t j-3k and C 2i+3j-k then find \(\frac{d}{d t}[\mathbf{A} \times(\mathbf{B} \times \mathbf{C})]\) at t =0

Solution: B× C\(=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}1 & \mathbf{k} & \mathbf{k} \\

\cos t & -\sin t & -3 \\2 & 3 & -1\end{array}\right|\)=i(sin t+9)-j(-cost+6) + k (3 cos t+2 sin t)

A x B x C = \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

\sin t & \cos t & t \\

\sin t+9 & \cos t-6 & 3 \cos t+2 \sin t

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(3 \cos ^2 t+2 \cos t \sin t-t \cos t+6 t\right)-\mathbf{j}\left(3 \sin t \cos t+2 \sin ^2 t-t \sin t-9 t\right)\)

+ \(\mathbf{k}(\sin t \cos t-6 \sin t-\sin t \cos t-9 \cos t)\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(3 \cos ^2 t+2 \cos t \sin t-t \cos t+6 t\right)-\mathbf{j}\left(3 \sin t \cos t+2 \sin ^2-t \sin t-9 t\right)\)

+ \(\mathbf{k}(-6 \sin t-9 \cos t)\)

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}[\mathbf{A} \times(\mathbf{B} \times \mathbf{C})]=\mathbf{i}\left(-6 \cos t \sin t+2 \cos ^2 t-2 \sin ^2 t+t \sin t-\cos t+6\right)\)

– \(\mathbf{j}\left(3 \cos ^2 t-3 \sin ^2 t+4 \sin t \cos t-t \cos t-\sin t-9\right)+\mathbf{k}(-6 \cos t+9 \sin t)\)

∴ \(\frac{d}{d t}[\mathbf{A} \times(\mathbf{B} \times \mathbf{C})]=7 \mathbf{t}=0 \mathbf{i}-6 \mathbf{k} \text {. }\)

21. If r is a vector function such that |r| = r then show that

(1) [r r’ r”]’=[r r’ r”’]

(2) [r×(r’×r”)]’= (r ×(r’×r”’)+ r×(r’×r”’).

Solution: (1) [r r’ r”]= [r’ r’ r”] + [r r” r”]+[r r’ r”’]=[r r’ r”’]

(2) [r×(r’×r”)]’=[r×(r’×r”)]’+[r×(r”×r”)]+[r×(r’×r”’)]

=r’×(r’×r”)+r×(r’×r”’)

22. Define the partial derivative of a vector function.

Solution:

Partial derivative: Let f = f (p, q, t) be a vector function of scalar variables that exists, then the limit is called the ”partial derivative” of f with respect to t. It is denoted by \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial f}\) . Similarly we can define \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial p}\),\(\frac{\partial f}{\partial q}\).

23. If f=cos xyi+(3xy-2x2)j-(3x+2y) k then find \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial x^2}\),\(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial x \partial y}\),\(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial y^2}\).

Solution:

f = \(\cos x y \mathbf{i}+\left(3 x y-2 x^2\right) \mathbf{j}-(3 x+2 y) \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x}=-y \sin x y \mathbf{i}+(3 y-4 x) \mathbf{j}-3 \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{d y}=-x \sin x y \mathbf{i}+3 x \mathbf{j}-2 \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial x^2}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x}\right)=-y^2 \cos x y \mathbf{i}-4 \mathbf{j}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial x \partial y}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial y}\right)\)

= \(-(x y \sin x y+\sin x y) \mathbf{i}+3 \mathbf{j}\)

∴ \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial y^2}=\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial y}\right)=-x^2 \cos x y \mathbf{i}\)

24.If f=(2x2y-x4)i+(exy-y sin x)j+(x2 cos y) k, find \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial x^2}\) and \(\frac{\partial^2 \mathbf{f}}{\partial x \partial y}\)

Solution:

Given

f=(2x2y-x4)i+(exy-y sin x)j+(x2 cos y) k

f = \(\left(2 x^2 y-x^4\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(e^{x y}-y \sin x\right) \mathbf{j}+\left(x^2 \cos y\right) \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}=\left(4 x y-4 x^3\right) \mathbf{I}+\left(y e^{x y}-y \cos x\right) \mathbf{j}+(2 x \cos y) \mathbf{k}\)

and \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \doteq 2 x^2 \mathbf{I}+\left(x e^{x y}-\sin x\right) \mathbf{j}-x^2 \sin y \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2}=\left(4 y-12 x^2\right) \mathbf{I}+\left(y^2 e^{x y}+y \sin x\right) \mathbf{j}+2 \cos y \mathbf{k}\)

and \(\frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x \partial y}=4 x \mathbf{I}+\left(x y e^{x y}+e^{x y}-\cos x\right) \mathbf{j}-2 x \sin y \mathbf{k} .\)

25. If f= a cos nt+b sin nt then prove that \(\frac{\partial^2 r}{\partial t^2}\)+n2 r =0 where a,b,n are constants .

Solution:

Given r = \(a \cos n t+b \sin n t\). Then \(\frac{\partial r}{\partial t}=-a n \sin n t+b n \cos n t\)

∴ \(\frac{\partial^2 r}{\partial t^2}=-a n^2 \cos n t-b n^2 \sin n t=-n^2(a \cos n t+b \sin n t)=-n^2 r \Rightarrow \frac{\partial^2 r}{\partial t^2}+n^2 r=0 \text {. }\)

26. If f=2x2i-3yzj+xz2k and φ=2z-x3y then find

(1) f. \(\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)\)

(2) \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x} \cdot\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{\jmath} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)\) and

(3) \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial z} \times\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)\) at (1,-1,1) .

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x}=4 x \mathbf{i}+z^2 \mathbf{k}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial z}=-3 y \mathbf{j}+2 x z \mathbf{k} . \text { At }(1,-1,1), \frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x}=4 \mathbf{i}+\mathbf{k}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial z}=3 \mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}=-3 x^2 y, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}=-x^3, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=2\)

At (1,-1,1), \(\mathbf{f}=2 x^2 \mathbf{i}-3 y z \mathbf{j}+x z^2 \mathbf{k}=2 \mathbf{i}+3 \mathbf{j}+\mathbf{k}\) and \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=\mathbf{i}\left(-3 x^2 y\right)+\mathbf{j}\left(-x^3\right)+\mathbf{k}(2)=3 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k}\)

1. \(\mathbf{f} \cdot\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)=(2 \mathbf{i}+3 \mathbf{j}+\mathbf{k}) \cdot(3 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k})=6-3+2=5\)

2. \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial x} \cdot\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)=(4 \mathbf{i}+\mathbf{k}) \cdot(3 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k})=12+2=14\)

3. \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{f}}{\partial z} \times\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)=(3 \mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k}) \times(3 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k})\)

= \(\left|\begin{array}{rrr}\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\ 0 & 3 & \mathbf{2} \\ 3 & -1 & 2\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{i}(6+2)-\mathbf{j}(0-6)+\mathbf{k}(0-9)=8 \mathbf{i}+6 \mathbf{j}-9 \mathbf{k}\).

Ordinary Derivatives Of Vector Functions Step-By-Step Solutions

27. If r=xi+yj+zk and a is a constant vector prove that

(1) \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial}{\partial y}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{k}\)=a

(2) \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial}{\partial y}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{I}+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{k}\)=-2a

Solution:

Let \(\mathbf{a}=a_1 \mathbf{i}+a_2 \mathbf{j}+a_3 \mathbf{k}\)

Given \(\mathbf{r}=x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}\)

Now \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x}=\mathbf{i}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial y}=\mathbf{j}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial z}=\mathbf{k}\).

1. \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial}{\partial y}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{k}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{a} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x}\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(\mathbf{a} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial y}\right) \mathbf{j}+\left(\mathbf{a} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial z}\right) \mathbf{k}\)

= \((\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{i}) \mathbf{i}+(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{j}) \mathbf{j}+(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{k}) \mathbf{k}=\mathbf{a}\)

2. \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{k}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x}\right) \times \mathbf{i}+\left(\mathbf{a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial y}\right) \times \mathbf{j}+\left(\mathbf{a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial z}\right) \times \mathbf{k}\)

= \((\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{i}) \times \mathbf{i}+(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{j}) \times \mathbf{j}+(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{k}) \times \mathbf{k}\)

= \((\mathbf{i} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{i}-(\mathbf{i} \cdot \mathbf{i}) \mathbf{a}+(\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{j}-(\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{j}) \mathbf{a}+(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{k}-(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{k}) \mathbf{a}\)

= \({[(\mathbf{i} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{i}+(\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{j}+(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{a}]-3 \mathbf{a}=\mathbf{a}-3 \mathbf{a}=-2 \mathbf{a} }\)

28. If f=yzi+zxj+xyk, prove that \(\mathbf{i} \times \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \times \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \times \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\)=0.

Solution:

f = \(y z \mathbf{i}+z x \mathbf{j}+x y \mathbf{k} \Rightarrow \frac{\partial f}{\partial \dot{x}}=z \mathbf{j}+y \mathbf{k}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}=z \mathbf{i}+x \mathbf{k}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}=y \mathbf{i}+x \mathbf{j}\)

⇒ \(\mathbf{i} \times \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \times \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \times \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}=\mathbf{i} \times(z \mathbf{j}+y \mathbf{k})+\mathbf{j} \times(z \mathbf{i}+x \mathbf{k})+\mathbf{k} \times(y \mathbf{i}+x \mathbf{j})\)

= \(z \mathbf{i}-y \mathbf{j}-z \mathbf{k}+x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}-x \mathbf{i}=\mathbf{0}\)

29. If φ=2xz4-x2y then find the value of \(\left|\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x} \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y} \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial k} \mathbf{k}\right|\) at (2,-2,-1).

Solution:

⇒ \(\phi=2 x z^4-x^2 y \Rightarrow \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}=2 z^4-2 x y, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}=-x^2, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z}=8 x z^3\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x} \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y} \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z} \mathbf{k}=\left(2 z^4-2 x y\right) \mathbf{i}-x^2 \mathbf{j}+8 x z^3 \mathbf{k}=(2+8) \mathbf{i}-4 \mathbf{j}-16 \mathbf{k}=10 \mathbf{i}-4 \mathbf{j}-16 \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\left|\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y} \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z} \mathbf{k}\right|=\sqrt{100+16+256}=\sqrt{372} .\)

30. If φ =x2yz+4xz2 and A=2i-j-2k , find A \(\left[\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right]\) at(2,-2,-1).

Solution:

⇒ \(\phi=2 x z^4-x^2 y \Rightarrow \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}=2 z^4-2 x y, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}=-x^2, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z}=8 x z^3\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x} \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y} \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z} \mathbf{k}=\left(2 z^4-2 x y\right) \mathbf{i}-x^2 \mathbf{j}+8 x z^3 \mathbf{k}=(2+8) \mathbf{i}-4 \mathbf{j}-16 \mathbf{k}=10 \mathbf{i}-4 \mathbf{j}-16 \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\left|\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y} \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z} \mathbf{k}\right|=\sqrt{100+16+256}=\sqrt{372}\) .

31. Define a scalar point function.

Solution:

Scalar point function: Let S be a domain in space. If to each point P ∈ S there corresponds a unique scalar (real number) φ (P) then the correspondence cp is called a “scalar point function” over the domain S.

32. Define a vector point function.

Solution:

Vector point function: Let S be a domain in space. If to each point P e S there corresponds a unique vector F (P) then the correspondence F is called a “vector point function “ over the domain S.

Vector Function Differentiation In Calculus For Beginners

33. Define distance function.

Solution:

Distance function: Let O be the origin in space. For each point P (x, y, z) in space if we define r (P) = OP = \(\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}\) then r is a scalar point function. It is called the “Distance function”.

34. Define the position vector point function

Solution:

Position vector point function: Let O be the origin in space. For each point P (x, y, z) in space if we define r (P)- \(\overrightarrow{O P}\) = xi+yj + zk, then r is a vector point function, r is called ”position vector point function”.

35. Define the directional derivative of a scalar point function.

Solution:

Directional derivative of scalar point function: Let φ be a scalar point function defined on a neighborhood D of a point P. Let L be a ray from P in the direction of the unit vector e. Let Q ∈ L ∩ D and Q≠ P. If \(\stackrel{L t}{Q \rightarrow P}\)\(\frac{\varphi(Q)-\varphi(P)}{Q P}\)exists then the limit is called the “Directional derivative“ of φ at P in the direction of e. It is denoted by \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial e}\) or \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\) when s = QP.

36. Define the directional derivative of a vector point function.

Solution:

Directional derivative of a vector point function: Let F be a vector point function defined on a neighborhood D of a point P. Let L be a ray from P in the direction of the unit vector e. Let Q ∈ L∩D and Q≠P If \(\) exist then the limit is called the “Directional derivative” of F at P in the direction of e. It is denoted by\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial e}\) when s = 0

37. If r is the position vector point function and e is a unit vector then prove that \(\frac{\partial r}{\partial e}\)=e

Solution:

Let P be a point and Q be a point in the ray from P in the direction of e such that Q≠P.

Let \(\mathbf{a}=a_1 \mathbf{i}+a_2 \mathbf{j}+a_3 \mathbf{k}\)

Given \(\mathbf{r}=x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}\)

Now \(\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x}=\mathbf{i}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial y}=\mathbf{j}, \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial z}=\mathbf{k}\).

1. \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial}{\partial y}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{r}) \mathbf{k}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{a} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x}\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(\mathbf{a} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial y}\right) \mathbf{j}+\left(\mathbf{a} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial z}\right) \mathbf{k}\)

= \((\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{i}) \mathbf{i}+(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{j}) \mathbf{j}+(\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{k}) \mathbf{k}=\mathbf{a}\)

2. \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{i}+\frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{j}+\frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{r}) \times \mathbf{k}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial x}\right) \times \mathbf{i}+\left(\mathbf{a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial y}\right) \times \mathbf{j}+\left(\mathbf{a} \times \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial z}\right) \times \mathbf{k}=(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{i}) \times \mathbf{i}+(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{j}) \times \mathbf{j}+(\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{k}) \times \mathbf{k}\)

= \((\mathbf{i} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{i}-(\mathbf{i} \cdot \mathbf{i}) \mathbf{a}+(\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{j}-(\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{j}) \mathbf{a}+(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{k}-(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{k}) \mathbf{a}\)

= \({[(\mathbf{i} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{i}+(\mathbf{j} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{j}+(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{a}) \mathbf{a}]-3 \mathbf{a}=\mathbf{a}-3 \mathbf{a}=-2 \mathbf{a} }\)

38. If r is the distance point function and e is a unit vector then prove that\(\frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial e}\) = r.e/ r.

Solution:

r= \(|\boldsymbol{r}| \Rightarrow r^2=\mathbf{r}^2 \Rightarrow \frac{\partial}{\partial \bullet}\left(r^2\right)=\frac{\partial}{\partial \bullet}\left(\mathbf{r}^2\right) \Rightarrow 2 r \frac{\partial r}{\partial \bullet}\)

= \(2 \mathbf{r} \cdot \frac{\partial \mathbf{r}}{\partial \bullet} \Rightarrow r \frac{\partial r}{\partial \bullet}=\mathbf{r} \cdot \bullet\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial r}{\partial \bullet}=\frac{\mathbf{r} \cdot \bullet}{r}\)

Understanding Vector Differentiation Exercises In Calculus

39. Define the gradient of a scalar point function.

Solution:

Gradient s If φ is a scalar point function having directional derivatives in the i,j,k then \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\)is called gradient of φ. It is denoted by grad φ or ∇φ.

40. If f and g are two scalar point functions then prove that

(1) grad (f±g)=grad f ±grad g

(2) grad (fg) =(grad f)g+ f (grad g)

(3) grad \(\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)\)=\(\frac{1}{g^2}\)[g (grad f)-f(grad g)](grad g)

Solution:

(1) \(\text{grad}(f+g)=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(f+g)+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(f+g)+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(f+g)\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial g}{\partial x}\right)+\mathbf{j}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial g}{\partial y}\right)+\mathbf{k}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}+\frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\right)\)

= \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\right)+\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\right)\)=\(\text{grad} f+\text{grad} g.\)

Similarly we can prove that \(\text{grad}(f-g)=\text{grad} f-\text{grad} g\).

(2) grad(f g) = \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(f g)+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(f g)+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(f g)\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x} g+f \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}\right)+\mathbf{j}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial y} g+f \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}\right)+\mathbf{k}\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} g+f \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\right)\)

= \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} g+\mathbf{i} f \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} g+\mathbf{j} f \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z} \mathbf{g}+\mathbf{k} f \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\right) g+f\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\right)=(g r a d f) g+f(\text{grad} g)\)

(3) \(\text{grad}\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)\)

= \(\mathbf{I} \frac{\left(g \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}-f \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}\right)}{g^2}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\left(g \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}-f \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}\right)}{g^2}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial z} g+f \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\right)}{g^2}\)

= \(\frac{1}{g^2}\left[g\left(\mathbf{I} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\right)-f\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}\right)\right]\)

= \(\frac{1}{g^2}[g(g r a d f)-f(g r a d g)]\)

41. If φ is a scalar point function and c is a scalar then prove that grad (c φ) = c (grad φ).

Solution:

grad\((c \varphi)=\mathbf{I} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(c \varphi)+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(c \varphi)+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(c \varphi)\)

= \(\mathbf{I} c \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} c \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} c \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\)

= \(c\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)=c(\text{grad} \varphi)\)

42. Prove that a scalar point function φ is constant if grad φ = 0.

Solution:

Suppose \(\varphi\) is constant. Then \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}=0, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}=0, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=0\)

∴ \(\text{grad} \varphi=1 \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathrm{J} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=0\)

Conversely, suppose that grad \(\varphi=0\).

Then \(I \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+J \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=0\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}=0, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}=0, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=0 \Rightarrow \varphi\) is constant.

43. If φ + x3-y3+x2 z then find grad φ at (1, 1,-2).

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}=3 x^2+2 x z, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}=-3 y^2, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=x^2\)

grad \(\varphi=\mathbf{1} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=\left(3 x^2+2 x z\right) \mathbf{1}-3 y^2 \mathbf{J}+x^2 \mathbf{k}\)

At (1,1,-2), \(\text{grad} \varphi=-\mathbf{I}-3 \mathbf{J}+\mathbf{k}\) .

44. Find grad f at the point (1, 1,- 2) where f= x3+y3+3xyz.

Solution:

f = \(x^3+y^3+3 x y z \Rightarrow \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}=3 x^2+3 y z, \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}=3 y^2+3 x z, \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}=3 x y\)

∴ grad f = \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}=\left(3 x^2+3 y z\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(3 y^2+3 x z\right) \mathbf{j}+3 x y \mathbf{k}\)

At (1,1,-2), \(\text{grad} f=(3-6) \mathbf{i}+(3-6) \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k}=-3 \mathbf{i}-3 \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k}\).

45. If φ= x3 +y3 + z3+ 3xyz then find grad φ at (1, 2, 3).

Solution:

Given

φ= x3 +y3 + z3+ 3xyz

⇒ \(\phi=x^3+y^3+z^3+3 x y z \Rightarrow \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}=3 x^2+3 y z, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}=3 y^2+3 x z, \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z}=3 z^2+3 x y\)

∴ grad \(\phi\)

= \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \phi}{\partial z}=\left(3 x^2+3 y z\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(3 y^2+3 x z\right) \mathbf{j}+\left(3 z^2+3 x y\right) \mathbf{k}\)

At(1,2,3), \(\text{grad} \phi=(3+18) \mathbf{i}+(12+9) \mathbf{j}+(27+6) \mathbf{k}=21 \mathbf{i}+21 \mathbf{j}+33 \mathbf{k}\) .

r = \(x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}\)

Then r= \(|\mathbf{r}|=\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2} \Rightarrow r^2=x^2+y^2+z^2\)

2 r \(\frac{\partial r}{\partial x}=2 x, 2 r \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}=2 y, 2 r \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=2 z \Rightarrow \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}=\frac{x}{r}, \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}=\frac{y}{r}, \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=\frac{z}{r}\)

⇒ \(\nabla r=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=\mathbf{i} \frac{x}{r}+\mathbf{j} \frac{y}{r}+\mathbf{k} \frac{z}{r}=\frac{x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}}{r}=\frac{\mathbf{r}}{r}\)

46. Show that ∇r\(=\frac{r}{r}\)

Solution:

r = \(x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}\)

Then r = \(|\mathbf{r}|=\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2} \Rightarrow r^2=x^2+y^2+z^2\)

2 r \(\frac{\partial r}{\partial x}=2 x, 2 r \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}=2 y, 2 r \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}\)=2 z

⇒ \(\frac{\partial r}{\partial x}=\frac{x}{r}, \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}=\frac{y}{r}, \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=\frac{z}{r}\)

∴ \(\nabla r=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=\mathbf{i} \frac{x}{r}+\mathbf{j} \frac{y}{r}+\mathbf{k} \frac{z}{r}=\frac{x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}}{r}=\frac{\mathbf{r}}{r}\)

47. Show that ∇\(\left(\frac{1}{r}\right)\)=\(\frac{-r}{r^3}\)

Solution:

⇒ \(\nabla\left(\frac{1}{r}\right)=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left\{\frac{1}{r}\right\}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left\{\frac{1}{r}\right\}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left\{\frac{1}{r}\right\}\)

= \(\mathbf{i}\left\{-\frac{1}{r^2}\right\} \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j}\left\{-\frac{1}{r^2}\right\} \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k}\left\{-\frac{1}{r^2}\right\} \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}\)

= \(-\frac{1}{r^2}\left[\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}\right]=-\frac{1}{r^2}\left[\mathbf{i} \frac{x}{r}+\mathbf{j} \frac{y}{r}+\mathbf{k} \frac{z}{r}\right]\)

= \(-\frac{1}{r^3}[x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k}]=-\frac{\mathbf{r}}{r^3}\)

48. show that ∇f(r) =f’ (r) \(=\frac{r}{r}\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\nabla f(r)=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\{f(r)\}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\{f(r)\}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\{f(r)\}=\mathbf{i} f^{\prime}(r) \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} f^{\prime}(r) \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} f^{\prime}(r) \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}\)

= \(f^{\prime}(r)\left[\mathbf{i} \frac{x}{r}+\mathbf{j} \frac{y}{r}+\mathbf{k} \frac{z}{r}\right]=f^{\prime}(r) \frac{\mathbf{r}}{r}\)

49. Show that ∇(log|r|)\(=\frac{r}{r^2}\)

Solution:

⇒ \(\nabla \log |r|=\mathbf{I} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\{\log |r|\}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\{\log |r|\}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\{\log |r|\}\)

= \(\mathbf{I} \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{1}{r} \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=\mathbf{I} \frac{1}{r} \frac{x}{r}+\mathbf{J} \frac{1}{r} \frac{y}{r}+\mathbf{k} \frac{1}{r} \frac{z}{r}=\frac{\mathbf{r}}{r^2}\)

50. If x+y+z,b=x2+y2+z2, c= xy+yz+zx then show that =0

Solution:

Given

If x+y+z,b=x2+y2+z2, c= xy+yz+zx

⇒ \(\nabla a=\left(\mathbf{1} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}+\mathbf{1} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\right)(x+y+z)\)

= \(\mathbf{I} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(x+y+z)+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x+y+z)+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(x+y+z)=\mathbf{1}+\mathbf{j}+\mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\nabla b=\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\right)\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)=2 x \mathbf{i}+2 y \mathbf{J}+2 z \mathbf{k}\)

⇒ \(\nabla c=\left(\mathbf{1} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}+\mathbf{J} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\right)(x y+y z+z x)=(y+z) \mathbf{I}+(x+z) \mathbf{\jmath}+(y+x) \mathbf{k}\)

51. Show that gradrm=m m-2r.

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(r^m\right)=m r^{m-1} \frac{\partial r}{\partial x}=m r^{m-1} \frac{x}{r}=m r^{m-2} x\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(r^m\right)=m r^{m-1} \frac{\partial r}{\partial y}=m r^{m-1} \frac{y}{r}=m r^{m-2} y\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(r^m\right)=m r^{m-1} \frac{\partial r}{\partial z}=m r^{m-1} \frac{z}{r}=m r^{m-2} z\)

grad \(r^m=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(r^m\right)+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(r^m\right)+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(r^m\right)=m r^{m-2} x \mathbf{i}+m r^{m-\dot{2}} y \mathbf{j}+m r^{m-2} z \mathbf{k}\)

= \(m r^{m-2}(x \mathbf{i}+y \mathbf{j}+z \mathbf{k})=m r^{m-2} \mathbf{r} \text {. }\)

52. Show that grad (r.a)=a

Solution:

Let a=a1i+a2j+a3k= , r= xi+yj=zk, r.a=a1x+a2y+a3z

grad(r.a) =∇(r.a)= \(=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(\mathbf{r} \cdot \mathbf{a})+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(\mathbf{r} \cdot \mathbf{a})+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(\mathbf{r} \cdot \mathbf{a})\)

= i a1+j a2+k a3=a.

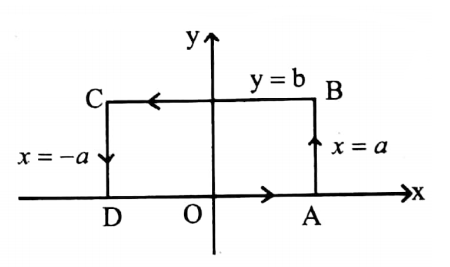

53. Define the level surface of a scalar point function.

Leval surface: Let φ be a scalar point function defined over the domain S and P ∈ S. The set of all points Q ∈ S such thatφ (Q)= φ (P) is called a “Level surface” of (p through P. If c is a constant then the set of all points Q (x,y, z) ∈ S such that φ (Q)- c is called a “Level surface” at the level c. It is denoted by φ(x,y,z) = c.

54. Prove that the directional derivative of a scalar point function φ at a point P in the direction of the unit e vector is (grad φ). e.

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial e}\)=\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\) =\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\)

+ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}\)\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\)

+ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\)\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\)

= \(\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right) \cdot\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial x}{\partial s}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial y}{\partial s}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial z}{\partial s}\right)\)

= (grad φ).e.

55. Find the directional derivative of φ =x2yz + 4x2z at the point (1, -2,- 1) in the direction of 2i − j −2k

Solution:

If e is the unit vector in the direction of 2i-j-2k then

e= \(=\frac{2 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}-2 \mathbf{k}}{|2 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}-2 \mathbf{k}|}=\frac{2 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}-2 \mathbf{k}}{3}\)

=\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}\)=2xyz+4z2, \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}\)=x2z,\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\)=x2y+8xz

grad φ =\(i \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+j \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\)(2xyz+4z2)i+(x2z)j+(x2y+8xz)k

The directional derivative of in the direction of e is (grad φ) e

⇒ \(=\frac{2\left(2 x y z+4 z^2\right)-x^2 z-2\left(x^2 y+8 x z\right)}{3}\)

At (1,-2,-1) , directional derivative \(=\frac{2(4+4)-(-1)-2(-2-8)}{3}\)=\(\frac{37}{3}\)

56. Find the directional derivative of φ=xyz at (1, 1, 1) in the direction of the vector i+j+kSolution:

grad φ \(=1 \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+k \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\) =yzi+xzj+xyz

It is the vector in the direction of I+J+K, then e \(=\frac{1+j+k}{\sqrt{1+1+1}}\)=\(\frac{1+j+k}{\sqrt{3}}\)

Directional derivative =(grad φ). e (yzi+xzj+xyk).(i+j+k)/\(\sqrt{3}\)

(yz+zx+xy)/\(\sqrt{3}\)

Directional derivative at (1,1,1) is (1+1+1)/\(\sqrt{3}\)=\(\sqrt{3}\).

57. Find the directional derivative of φ= xy + yz + zx at the point (1, 2, 0) in the direction i+2j+2k.

Solution:

If e is the unit vector in the direction of i+2j+2k, then

e \(=\frac{\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k}}{\sqrt{1+4+4}}\)=\(\frac{\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}+2 \mathbf{k}}{3}\)

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}\)=y+z,\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}\)=x+z,\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}\)=y+x.

grad φ =\(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\)=(y+z)i+(z+x)j+(x+y)k

The directional derivative of in the direction of e is

(grad φ) . e\(=\frac{(y+z)+2(x+z)+2(y+x)}{3}\)

At directional (1,2,0) derivative \(=\frac{(2+0)+2(1+0)+2(2+1)}{3}\)=\(\frac{10}{3}\).

58. Find the directional derivative of φ =xy+yz+zx at A in the direction of \(\overrightarrow{A B}\) where A=(1,2,-1) , B=(-1,2,3).

Solution:

f = xy+yz+zx

grad f = \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}=(y+z) \mathbf{i}+(z+x) \mathbf{j}+(x+y) \mathbf{k}\)

A B =(-1-1) \(\mathbf{i}+(2-2) \mathbf{j}+(3+1) \mathbf{k}=-2 \mathbf{i}+4 \mathbf{k}\)

If is the unit vector in the direction of -2 i+4 k then \(\frac{-2 i+4 k}{\sqrt{4+16}}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{5}}(-1+2 k)\)

∴ The directional derivative =\(\mathbf{e} \cdot \text{grad} f\)

= \((1 / \sqrt{5})(-\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{k}) \cdot[(y+z) \mathbf{i}+(z+x) \mathbf{j}+(x+y) \mathbf{k}]=(1 / \sqrt{5})[-y-z+2 x+2 y]\)

= \((1 / \sqrt{5})[2 x+y-z]=1 / \sqrt{5}(2+2+1)\) at (1,2,-1)=\((5 / \sqrt{5})=\sqrt{5}\) at (1,2,-1)

59. Find the directional derivative of f=x2-y2 + 2z2 at the point P(1, 2, 3) in the direction of the line \(\overrightarrow{P Q}\)where Q = (5, 0, 4).

Solution:

Given that \(\overrightarrow{OP}\) =i+2j+3k,\(\overrightarrow{OQ}\) = 5i+4k.

∴ \(\overrightarrow{PQ}\)=\(\overrightarrow{OQ}\)–\(\overrightarrow{OP}\) = 4i-2j+k.

Unit vector in the direction of \(\overrightarrow{PQ}\) is

e = \(\frac{\overrightarrow{P Q}}{|\overrightarrow{P Q}|}\) = \(\frac{4 i-2 j+k}{\sqrt{16+4+1}}\) = \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{21}}(4 i-2 j+k)\)

∇ f \(=i \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+i \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+k \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\)=12x+j(-2y)+k(4z)

Directional derivative =e.∇f

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{21}}(4 i-2 j+k) \cdot(2 x i-2 y j+4 z k)\)

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{21}}(8 x+4 y+4 z)\)

60. Find the directional derivative of φ = xy +yz2 +x2 along the tangent to the curve x = t,y = t2,z = t3 at (1, 1, 1)

Solution:

The position vector of any point on the given curve is r=xi+yj+zk

⇒ r= ti+t2j+t3k

⇒ \(\frac{d r}{d t}\)= i+2tj+3t2k

Unit vector along the tangent is e \(=\frac{\mathbf{i}+2 t \mathbf{j}+3 t^2 \mathbf{k}}{\sqrt{1+4 t^2+9 t^4}}\)=\(\frac{\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k}}{\sqrt{14}}\) at (1,1,1)

Directional derivative along e is ∇φ \(\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)\).e

=[i(y2+2x)+j(2xy+z2) +k (2yz)].e

=(3i+3j+2k). \(\frac{(\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k})}{\sqrt{14}}\)

=\(=\frac{3+6+6}{\sqrt{14}}\)

=\(\frac{15}{\sqrt{14}}\) at(1,1,1).

61. Find the directional derivative of the function xy2+yz2+ zx2 along the tangent to the curve x =t,y = t2, z = t3at the point (1, 1, 1).

Solution:

The position vector of any point on the given curve is r=xi+yj+zk

⇒ r=ti+t2j+t3k

⇒ \(\frac{d r}{d t}\) = i+2tj+3t2k

Unit vector along the tangent is e \(=\frac{\mathbf{i}+2 t \mathbf{j}+3 t^2 \mathbf{k}}{\sqrt{1+4 t^2+9 t^4}}\)=\(\frac{\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k}}{\sqrt{14}}\) at(1,1,1)

Let φ =xy2+yz2+zx2

The directional derivative of φ along e is ∇ φ .e \(=\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right)\).e

=[i(y2+2zx)+j(2xy+z2)+k (2yz+x2)].e

= (3i+3j+3k).\(\frac{(\mathbf{i}+2 \mathbf{j}+3 \mathbf{k})}{\sqrt{14}}\)

= \(\frac{3+6+9}{\sqrt{14}}\)

∴ \(\frac{18}{\sqrt{14}}\) at (1,1,1).

62. Prove that g grad φ is a normal vector to the level surface φ (x,y, z) = c where c is constant.

Solution:

Let p(x,y,z) be a point on the level surface and T be the unit tangent vector at P The position vector of P is r= xi+yj+zk

∴\(\frac{\partial r}{\partial s}=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial x}{\partial s}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial y}{\partial s}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial z}{\partial s}\)

φ (x,y,z) = c ⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\)=0

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x} \frac{\partial x}{\partial s}+\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial s}+\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z} \frac{\partial z}{\partial z}\)=0

\(\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}\right) \cdot\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial x}{\partial s}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial y}{\partial s}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial z}{\partial s}\right)\)=0

⇒ (grad φ). \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\)=0

⇒ (grad φ). T =0 ⇒ grad φ is perpendicular to T

⇒ grad φ is a normal vector to the level surface φ(x,y,z)=c.

63. If φ is a scalar point function then prove that\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\) direction of grad φ.

Solution:

The directional derivative of φ at a point P in the direction of a unit vector e is

\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\) =(grad φ ) .e =\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial N}\)N.e where N is the normal vector to the surface. at P.

∴ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\)=\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial N}\) |N| |e| cos (N,e) = \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial N}\) cos (N,e)

\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\) has maximum ⇔ cos (N,e) = 1 ⇔ N=e.

∴ The directional derivative has maximum value along the normal to the surface.

∴ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial s}\) has maximum value in the direction of grad φ

Maximum value of the directional derivative=\(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial \mathbf{N}}\)=|grad φ|

64 Find the maximum value of the directional derivative of φ = 2x2-y-z4 at (2,1,-1)

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}=4 x, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}=-1, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=-4 z^3\)

grad \(\varphi=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=4 x \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}-4 z^3 \mathbf{k}\)

At (2,-1,1), \(\text{grad} \varphi=8 \mathbf{i}-\mathbf{j}-4 \mathbf{k}\)

Maximum value of the directional derivative of \(\varphi\) at (2,-1,1) is \(|\text{grad} \varphi|=\sqrt{64+1+16}=\sqrt{81}=9\)

65. Find the greatest value of the directional derivative of the function f=£y£ at (2, 1,-1).

Solution:

grad f=2xyzi+xzj+3xyzk= -4i-4j+12k at (2,-1,1)

∴ Greatest value directional derivative of f = |∇f| =\(\sqrt{16+16+44}\)=\( \sqrt{11}\).

66. Find the maximum value of the directional derivative and the direction of the directional derivative when it is maximum, of φ =xy+ 2yz + 3xz at the point (1, 1, 1).

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}=y+3 z, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}=x+2 z, \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=2 y+3 x\)

grad \(\varphi=\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial z}=(y+3 z) \mathbf{i}+(x+2 z) \mathbf{j}+(3 x+2 y) \mathbf{k}\)

At(1,1,1), \(\text{grad} \varphi=4 \mathbf{i}+3 \mathbf{j}+5 \mathbf{k}\)

Maximum value of the directional derivative of \(\varphi\) at (1,1,1) is \(|\text{grad} \varphi|\)

= \(\sqrt{16+9+25}=5 \sqrt{2}\)

A directional derivative is maximum in the direction of the unit normal vector N.

N = \(\frac{\text{grad} \varphi}{|\text{grad} \varphi|}=\frac{4 \mathbf{i}+3 \mathbf{j}+5 \mathbf{k}}{5 \sqrt{2}}\)

67. Define the angle between two surfaces.

Solution:

The angle between surfaces: Let P be a point of intersection (common point) to the level surfaces f(x, y, z) = 0,g (x, y, z) = 0. The angle between the normals to the surfaces f(x,y, z) = 0, g (x,y, z) = 0 at P is called the “Angle between the surfaces” at P.

68. Find the angle between the surfaces of the spheres x2+y2 + z2 = 29, x2 +y2 + z2 + 4x- 6y- 8z- 47 = 0 at the point (4,- 3, 2).

Solution: Let f=x2+y2 + z2 − 29, g=x2 +y2 + z2 + 4x- 6y- 8z- 47

grad f = \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}=2 x \mathbf{i}+2 y \mathbf{j}+2 z \mathbf{k}\)

grad g = \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial g}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial g}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial g}{\partial z}=(2 x+4) \mathbf{i}+(2 y-6) \mathbf{j}+(23-8) \mathbf{k}\)

At (4,-3,2), \(\text{gradf}=8 \mathbf{i}-6 \mathbf{j}+4 \mathbf{k}=\mathbf{a}\) (say), \(\text{grad} g=12 \mathbf{i}-12 \mathbf{j}-4 \mathbf{k}=\mathbf{b}\) (say).

Now \(\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b}\) are normal vectors to the surfaces at (4,-3,2)

∴ Angle between the surfaces at (4,-3,2) is equal to \((\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b})\).

⇒ \(\cos (\mathbf{a}, \dot{b})=\frac{\mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{b}}{|\mathbf{a}||\mathbf{b}|}=\frac{(8 \mathbf{i}-6 \mathbf{j}+4 \mathbf{k}) \cdot(12 \mathbf{I}-12 \mathbf{j}-4 \mathbf{k})}{\sqrt{64+36+16} \sqrt{144+144+16}}\)

= \(\frac{96+72-16}{\sqrt{166} \sqrt{304}}=\frac{152}{\sqrt{116 \times 304}}=\sqrt{\frac{19}{29}}\)

∴ \((\mathbf{a}, \mathbf{b})=\text{Cos}^{-1}\left(\sqrt{\frac{19}{29}}\right)\)

69. Find the angle between the surfaces x2+y2+z2=9 and =x2+y2−z=3

Solution:

Let f=x2+y2+z2-9 and g=x2+y2+z2-3

∇f = \(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}\)=2xi+2yj+2zk. At( 2,-1,2), ∇f=4I-2J+4K

The normal to the surface x+y+z= 9 at (2,-1,2), is 4i-2j+4k

= \(2xi+2yj-k At (2,-1,2), g=4i-2j-kx\)

The normal to the surface z= x2+y2-z at (2,-1,2) is 4i-2j+4k

If θ is the angle between the surfaces at (2,-1,2) then

cos θ \(=\frac{(4 \mathbf{i}-2 \mathbf{j}+4 \mathbf{k}) \cdot(4 \mathbf{i}-2 \mathbf{j}-\mathbf{k})}{|4 \mathbf{i}-2 \mathbf{j}+4 \mathbf{k}||4 \mathbf{i}-2 \mathbf{j}-\mathbf{k}|}\)

= \(\frac{16+4-4}{\sqrt{16+4+16} \sqrt{16+4+1}}\)

= \(\frac{16}{6 \sqrt{21}}\)=\(\frac{8}{3 \sqrt{21}}\)

∴ Angle between the surfaces = Cos-1\((8 / 3 \sqrt{21)}\)