The use of numbers was existed for many centuries and we are familiar with the types of numbers – integers, rational numbers, real numbers, and complex numbers together with certain operations, such as addition and multiplication, defined on them.

The addition is basically just such a rule that people learn, enabling them to associate, with two numbers in a given order, some number as the answer. Multiplication is also such a rule, but a different rule.

But with the use of arbitrary quantities a,b,c,…, for numbers the subject, Algebra which is the generalization of Arithmetic, came into being. For many years mathematicians concentrated on improving the methods to use numbers, and not on the structure of the number system.

In the nineteenth century, mathematicians came to know that the methods to use numbers are not limited to only sets of numbers but also to other types of sets. A set with a method of combination of the elements of it is called an algebraic structure and we can have many algebraic structures.

The study of algebraic structures which have been subjected to axiomatic development in terms of Abstract Algebra. In what follows we study Group Theory i.e. the study of the algebraic structure. Group, which is rightly termed the basis of Abstract Algebra.

In Group Theory the basic ingredients are sets, relations, and mappings. It is expected that the student is very much familiar with them. However, we introduce and discuss some of the aspects connected with them which will be useful to us in our future study.

Binary Operations Equality Of Sets A And B

A ⊆ B And B ⊆ A ⇔ A = B

Binary Operations Union And Intersection Of Sets A1, A2, . . . , An

A1 ∪ A2 ∪ A3 . . . ∪ An = S ni =1 Ai and A1 ∩ A2 ∩ A3 . . . ∩ An = Tni =1 Ai

Binary Operations f Is A Relation From A Set A TO A Set B

⇔ f ⊆ A × B. ⇔ f ⊆ {(a, b) : a ∈ A, b ∈ B}

We write (a, b) ∈ f as afb and we say that a is f related to b.

Sometimes we write ∼ for f. In such a case we write a ∼ b.

If A = B, then we say that f is a relation in A.

If f ⊆ A × B, we write f−1 = {(b, a)/(a, b) ∈ f} ⊆ B × A and f−1 is called

inverse relation of f and it is from B to A.

The domain of f is equal to the range of f−1 and the range of f is equal to the domain of f−1. Further (f−1)-1= f.

f is a relation in A ⇔ f ⊆ A × A ⇔ f{(a, b)/a, b ∈ A} ⊆ A ∈ A.

Binary Operations Types Of Relations

f is a relation in a set A.

(1) If ∀x ∈ A, (x, x) ∈ f then f is said to be reflexive in A.

(2) If ∀(x, y) ∈ f ⇒ (y, x) ∈ f, then f is said to be symmetric in A.

(3) If (x, y) ∈ f and (y, z) ∈ f ⇒ (x, z) ∈ f, then f is said to be transitive in A.

(4) If f is reflexive, symmetric and transitive, then f is said to be an equivalence relation.

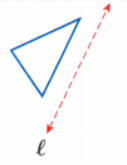

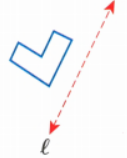

Example: 1. In the set of triangles in a plane, the relation of similarity is an equivalence relation.

2. A = {1, 2, 3} the relation f = {(1, 1), (2, 2), (3, 3)} is an equivalence relation in A.

Partition of a set

A partition of a set S is a set of non-empty subsets Si, with i in some index set ∆, such that:

(1). s = ∪i ∈∆si and

(2) si ∩ sj = φ for i 6= j.

That is, a partition of a set S is a collection of disjoint subsets of S whose union is the whole set S.

Binary Operations Partition Of A Set

f is an equivalence relation in a non-empty set S and a is an element of S.

The subset of elements which are f related to a constitutes an equivalence class of a.

The equivalence class of a is denoted by a¯ or [a] or {a}. Thus a¯ = {x ∈ S afx} and a¯ ⊆ S.

Further

(1) a ∈ a¯,

(2) b ∈ a¯ ⇒ ¯b = ¯a.

For, b ∈ a¯ ⇒ afb and x is any element of ¯b ⇒ bfx.

Now a fb, bfx ⇒ afx ⇒ x ∈ a¯ ⇒ ¯b ⊆ a¯

Again y is any element of a¯ ⇒ afy.

Since f symmetric a f b ⇒ bfa.

Now bfa, afy ⇒ bfy ⇒ y ∈ ¯b ⇒ a¯ ⊆ ¯b and hence ¯b = ¯a using (1).

(3) a¯ = ¯b ⇒ afb

For a¯ = ¯b ⇒ a ∈ ¯b ⇒ bfa ⇒ afb.

(4) afb˙ ⇒ a¯ = ¯b

For x ∈ a, afb¯ ⇒ afx, bfa ⇒ bfa, afx ⇒ bfx ⇒ x ∈ ¯b ⇒ a¯ ⊆ ¯b . . …

Again y is any element of ¯b ⇒ bfy.

Now a fb ⇒ afy ⇒ y ∈ a¯ ⇒ ¯b ⊆ a¯ and hence a¯ = ¯b using (2).

Theorem 1. If f is an equivalence relation in a non-empty set S and a, b are two arbitrary elements of S, then

(1) a¯ = ¯b or a¯ ∩ ¯b = φ

(2) a¯ ∪ ¯b ∪ c¯ ∪ .. = S

Proof.

Given

If f is an equivalence relation in a non-empty set S and a, b are two arbitrary elements of S,

(1) If a¯ ∩ ¯b = φ, there is nothing to prove. Let a¯ ∩ ¯b = φ.

Then there exists some element x such that x ∈ a¯ and x ∈ ¯b.

∴ afx and bfx ⇒ afx and xfb ⇒ af : b ⇒ a¯ = ¯b

Hence we must have either a¯ = ¯b if a¯ ∩ ¯b 6= φ or a¯ 6= ¯b if a¯ ∩ ¯b = φ.

(2) Let c be any element of S.

If afc, then a¯ = ¯c, and if bfc then ¯b = ¯c.

If a¯ 6= ¯c or ¯b 6= ¯c, then a¯ ∩ ¯b ∩ c¯ = φ.

∴ Every element of S must belong to some equivalence class of S

i.e. all the elements of S must belong to the disjoint equivalence classes of S

i.e. a¯ ∪ ¯b ∪ c¯ ∪ . . . = S.

Note. If f is an equivalence relation defined in a non-empty set S, the set of equivalence classes related to f is a partition of S.

That is, two equivalence classes related to f are

(1) either identical or disjoint and

(2) the union of all the disjoint equivalence classes of f is the set S.

Theorem 2. For any given partition of a set S, there exists an equivalence relation f in S such that the set of equivalence classes related to f is the given partition.

Proof. Let P = {Sa, Sb, Sc, . . . ..} be any partition of S.

Let p, q ∈ S.

Let us define a relation f in S by pfq if there is a Si in the partition such that p, q ∈ Si.

(1) Since S = S a ∪ S b ∪ S c ∪ . . . . . . , ∀x˙ ∈ S, there exists Si ∈ P such that x ∈ Si.

Hence x, x ∈ Si ⇒ xfx.

∴ f is reflexive in S.

(2) If xfy, then there exists Si ∈ P such that x, y ∈ Si.

But x, y ∈ Si ⇒ y, x ∈ Si ⇒ yfx. Hence xfy ⇒ yfx.

∴ f is symmetric in S.

(3) Let xfy and yfz then by the definition of f, there exist subsets Sj and Sk (not necessarily distinct) of S such that x, y ∈ Sj and y, z ∈ Sk.

Since y ∈ Sj and also y ∈ Sk, we have Sj ∩ Sk 6= φ.

But Sj, Sk belong to the partition of S.

∴ Sj ∩ Sk 6= φ ⇒ Sj = Sk

Then x, z ∈ Sj and hence xfz.

Hence f is transitive in S.

∴ f is an equivalence relation in S.

Binary Operations Functions Or Mappings

Definition. A, B are non-empty sets. If f ⊆ A × B such that the following conditions are true, then f is called a function from A, to B.

(1) ∀x ∈ A∃y ∈ B

such that (x, y) ∈ f.

(2) (x, y), (x, z) ∈ f ⇒ y = z.

If f is a function from A to B then we say that f is a mapping from A to B and we write f: A → B.

Domain of f is A and range of f is f(A) and f(A) ⊆ B.

Alternatively, if f is a relation that associates every element of A to an element of B, and if x = y ⇒ f(x) = f(y) for x, y ∈ A, then f is a function from A to B.

In this context, we say that the function is well-defined.

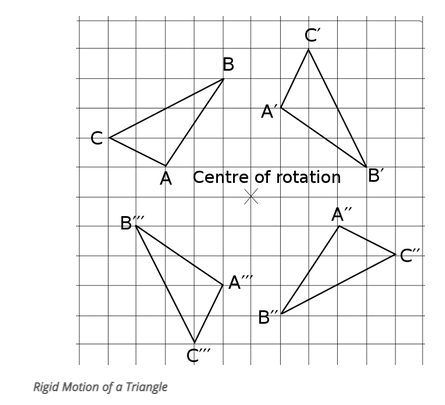

Transformation. If f: A → A then the function f is called an operator or transformation on A.

Equality of Functions. If f : A → B and g : A → B and if f(x) = g(x) for every x ∈ A then f = g. If ∃x ∈ A such that f(x) 6= g(x) then we say that f ≠ g.

Binary Operations 1.8 Types Of Functions Or Mappings

(1) If f; A → B is such that there is at least one element in B which is not the f image of any element in A, then we say that f is a mapping from A into B

i.e. f maps A into B.

(2) If f : A → B is such that f(A) = B, then we say that f is a mapping from A into B · f is also called a surjection or a surjective mapping.

If ∃ some element b ∈ B such that f(a) 6= b for some a ∈ A, then f is not onto.

(3) If f : A → B is such that for x, y ∈ A, f(x) = f(y) ⇒ x = y, then f is said to be a one-one or one-to-one function or an injection or an injective mapping. We write f as 1 − 1.

If x, y ∈ A and x 6= y ⇒ f(x) 6= f(y), then f is 1 − 1.

This is equivalent to the above condition.

If f(x) = f(y) does not imply x = y then we say that f is not 1 − 1.

(4) If f : A → B is 1 − 1 and onto, then f is called a bijection.

In other words we say that f is a 1 − 1 function from A onto B. Here f is called a one-one correspondence between A and B.

If A, B are finite and if f : A → B is a bijection then the number of elements in A, B are equal.

(5) If f : A → B is such that every element of A is mapped into one and only one element of B, then f is called a constant function. Here f (A) is a singleton set.

(6) If f : A → A is such that f(x) = x for every x ∈ A, then f is called the identity function on A. It is denoted by I A or simply I. I is always 1 − 1 and onto.

(7) If f : A → B is a bijection then f − 1 : B → A is unique and is also a bijection. If f : A → B, is one-one and onto, then f − 1 : B → A where f − 1 = {(b, a)/(a, b) ∈ f) is called the inverse mapping of f.

Here f(a) = b ⇔ f − 1(b) = a.

Only bijections possess inverse mappings.

Binary Operations Product Or Composite Of Mappings And Some Of Their Properties

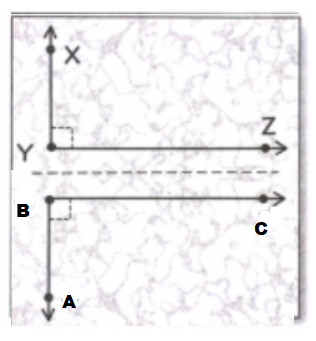

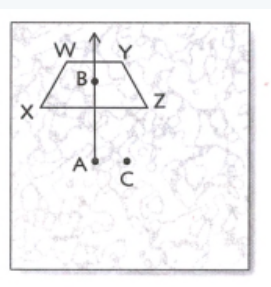

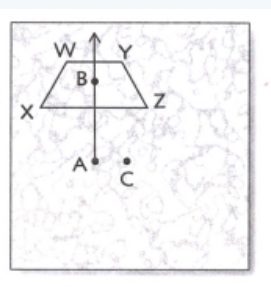

1. Let f : A → B and g : B → C.

Then the composite function of f and g, denoted by gof is a mapping from A to C.

i.e. gof : A → C such that (g ◦ f)(x) = g[f(x)], ∀x ∈ A.

Here fog cannot be defined. Even if it is possible to define fog and gof, then we may have fog 6= gof. Thus composition of mappings is not commutative:

2. If f : A → B and g : B → C are one-one, then gof : A → C is one-one.

If f, g are onto, then gof is onto.

If f, g are functions such that gof, is one-one, then f is one-one.

If f, g are functions such that gof is onto, then g is onto.

3. If f: A → B is a bijection, thenf−1: B → A. Also f−1of = I A and fof−1=IB.

In particular, if f: A → A is a bijection, then f−1 : A → A.

Also of = f◦ f−1 = I.

4. If f : A → B then I Bof = f and foI A = f.

In particular, if f: A → A then Iof = foI = f.

5. If f : A → B and g : B → C are bijections, then gof : A → C is also a bijection. If f, g are functions such that gof is a bijection then f is one-one and g is onto. In particular, if f, and g are bijections on A, then gof is also a bijection on A. Also (g ◦ f)−1 is a bijection and (g ◦ f)− 1 = f−1og−1

6. If f : A → B, g : B → C and h : C → D, then (h ◦ g) of = ho( gof ) i.e. composition of mappings is associative.

Definition. f : A → A is a function. fn: A → A where n ∈ Z is defined as follows.

- If n = 0, f 0 = I the identity mapping on A.

- If n = 1, f 1 = f

- If n ≥ 2 and n ∈ N, fn = f◦fn − 1 = fn − 1 of .

- If n is a negative integer and f is a bijection then fn = f−1� −n.

7. f2 = f ◦ f, f3 = f ◦ f 2 = fofof . . . . . . fn = fo f−1= fofof ….. to n times where n ∈ N.

8. If n is a negative integer and n = −m so that m is a positive integer, then fn = f−m = � f−1� m = f−1o f−1o f−1o . . . . . . to m times

= ( fofof . . . . . . to m times ) −1 = (fm)−1

9. If f : A → A is a bijection, then fn : A → A for n ∈ Z is also a bijection.

10. If m, n ∈ Z then fmofn = fm +n = fn +m = fnofm.

Binary Operations Binary Operations

Let R be the set of real numbers and addition (+), multiplication (x), and subtraction (−) be the operations in R. For every pair of numbers a, b ∈ R, we have unique elements a + b, a × b, a − b ∈ R.

Thus we can look upon addition, multiplication, and subtraction as three mappings of R × R into R, which for each element (a, b) of R × R determine the elements a + b, a × b, a − b respectively of R, Also one can define many mappings from R× R into R.

All these mappings are examples of binary operations on R. The idea of binary operation is not limited only to the sets of numbers. For example, the operations of union (∪), intersection (∩), and difference (−) are binary operations in P(A), the power set of A.

Binary operation

Definition. Let S be a non-empty set. If f : S × S → S is a mapping, then f. is called binary operation or binary composition in S (or on S ).

Thus

1. If a relation in S is such that every pair (distinct or equal) of elements of S taken in definite order is associated with a unique element of S then it is called a binary operation is S. Otherwise the relation is not a binary operation in S and the relation is simply an operation in S.

2. (a, b˙ ) ∈ S × S, ∃ a unique image f(a, b) ∈ S.

We observe that addition (+), multiplication (× or :), and subtraction (−) are binary operations in R and division (÷) is not a binary operation in R.

( ∵ division by 0 is not defined.)

Symbolism. It is customary to denote the binary operation in S by o (read as a circle) or (read as star) or . or + and to take a, b, c ∈ S as arbitrary elements a, b, c of S.

1. For a ∈ S, b ∈ S ⇒ a + b ∈ S ⇒ + is a binary operation in S. Also + is called addition, + is called usual addition if S ⊆ C and a + b is called the sum of a and b. Addition (+) is to be understood depending upon the set over which the operation is to be taken.

2. For a ∈ S, b ∈ S ⇒ a · b ∈ S ⇒. is a binary operation in S. Also . is called multiplication, . is called usual multiplication if S ⊆ C and a.b is called product of a, b. Multiplication (.) is to be understood depending upon the set over which the operation is to be taken.

3. For a ∈ S, b ∈ S ⇒ aob ∈ S ⇒ o is a binary operation in S.

4. For a ∈ S, b ∈ S ⇒ a ∗b ∈ S ⇒ ∗ is a binary operation in S.

This is called closure law.

Sometimes we write products a · b or a ∗b of a and b as ab.

If a, b ∈ S such that aob /∈ S then o is not a binary operation in S. In this case we say that S is not closed under; o.

+ is a binary operation in the set of natural numbers N as (a, b) ∈ N ⇒ a + b ∈ N.

• is not a binary operation in N as (a, b) ∈ N does not imply a − b ∈ N.

o is a binary operation in S. The image elements under the mapping o are in S. If a and b are elements of a subset H of S, it may or may not happen that ab ∈ H.

But if ab ∈ H for arbitrary elements a, b ∈ H the subset H is said to be closed under the operation o.It may be observed that if o is a binary operation in S, it is implied that S is closed under the operation o :

o is a binary operation in S. If a, b ∈ S and a 6= b, we know that (a, b) 6= (b, a), and hence, in general, it is not necessary that the images in S of (a, b) and (b,a) under the binary operation o must be equal. In other words, if o is a binary composition in S it is not necessary that a, b ∈ S must hold aob = boa.

+ is a binary operation in R. If a, b, c ∈ R, then a + b ∈ R, b + c ∈ R, (a + b) + c ∈ R and a + (b + c) ∈ R. We observe that (a + b) + c = a + (b + c).

Again – is a binary operation in R. If a, b, c ∈ R as above we observe that (a − b) − c ∈ R and a − (b − c) ∈ R. But (a − b) − c 6= a − (b − c).

Definition. o is a binary operation in a set S. If for a, b ∈ S, aob = boa, then o is said to be commutative in S. This is called commutative law. Otherwise, o

is said to be not-commutative, in S.

Definition. o is a binary operation in a set S. If for a, b, c ∈ S, (aob)oc = ao(boc) then o is said to be associative in S.

This is called associative law. Otherwise, o is said to be not associative in S.

Note. If o is associative in S, then we write (aob)oc = ao(boc) = aoboc e.g. is a commutative binary operation on N ⇒ a ∗ (b ∗ c) = (b ∗ c) ∗ a = (c ∗ b) ∗ a

Definition. o, ∗ are binary operations in a set S.

If a, b, c ∈ S,

(1) ao(b ∗ c) = (a ◦ b) ∗ (a ◦ c),

(2) (b ∗ c)oa = (b ◦ a) ∗ (c ◦ a),

then o is said to be distributive w.r.t. the operation *.

(1) is called the left distributive law and

(2) is called the right distributive law.

(1) and (2) are called distributive laws.

It is customary in mathematics to omit the words and only if from a definition. Definitions are always understood to be if and only if statements. Theorems are not always if and only if statements and no such convention is ever used for theorems.

Note. To prove that a binary operation in S obeys (follows) a law (commutative law, associative law, etc., ) we must prove that elements of every ordered pair obey the law i.e., the law must be proved by taking arbitrary elements.

But to prove that a binary operation in S does not obey a particular law, it is sufficient if we give a counter-example. This method of proving the result is called the proof by counter-example.

Example: 1. Set of Natural numbers N

(1) +,. are binary’operations in N, since for a, b ∈ N ⇒ a + b ∈ N and ab ∈ N. In other words, N is said to be closed w.r.t. the operation + and.

(2) +,. are commutative in N since for a, b ∈ N, a + b = b + a and ab = ba.

(3) +, are associative in N since for a, b, c ∈ N. (a + b) + c = a + (b + c) and a(bc) = (ab)c.

(4) – is distributive w.r.t. the operation + in N since for a, b, c ∈ N. a · (b + c) = a · b + a · c and (b + c) · a = b · a + c.a.

(5) The operations subtraction (−) and division (÷) are not binary operations in N for 3, 5 ∈ N does not imply 3 − 5 ∈ N and 3/5∈ N.

(6) Operations +, −, · are binary operations on R but ÷ is not. However, ÷ is a binary operation on R ∗ = R − {0}.

(7) On Z+, ∀a, b ∈ Z+if ∗ is defined as a ∗ b = ab or a ∗ b = |a − b|, then ∗ is a binary operation.

(8)In N, o is a binary operation defined as aob = L. C. M. for every a, b ∈ N. Then 7o5 = 35 and 16o20 = 80.

Example: 2. A is the set of even integers.

(1) +,. are binary operations in A since for a, b ∈ A, a + b ∈ A and ab ∈ A.

(2) +,. are commutative in A since for a, b ∈ A, a + b = b + a and ab = ba.

(3) +, . . . are associative in A since for a, b, c ∈ A,(a + b) + c = a + (b + c) and a(bc) = (ab)c.

(4) is distributive w.r.t. the operation + in A since for a, b, c ∈ A, a.(b + c) = a · b + a · c and (b + c) · a = b · a + c · a.

Example: 3. A is the set of odd integers.

(1) – is a binary operation in A. Also: is associative and commutative in A.

(2) + is not a binary operation in A since 3, 5 ∈ A does not imply 3 + 5 = 8 ∈ A.

Example: 4. S is the set of all m × n matrices such that each element of any matrix is a complex number.

The addition of matrices, denoted by +, is a binary operation in S. Also +)is commutative and associative in S.

Example: 5. S is the set of all vectors.

(1) Addition of vectors, denoted by + is a binary operation in S. Also + is commutative and associative in s.

(2) Dot product of vectors, denoted ., is not a binary operation in S since for a,¯ ¯b ∈ S, a¯ · ¯b /∈ S.

(3) Cross product of vectors denoted by × is a binary operation in S since for a,¯ ¯b ∈ S, a¯ × ¯b = ¯c ∈ S.

Example: 6. In N the operation o defined by aob = aab+b is not a binary operation.

Example: 7. ’ o ’ is a composition in R such that aob = a + 3b for a, b ∈ R.

(1) Since a, b ∈ R, a + 3b is a real number and hence a + 3b ∈ R i.e. aob ∈ R. Therefore o is a binary operation in R.

(2) a ◦ b = a + 3b and boa = b + 3a Since abb 6= boa for a, b ∈ R, 0o ’ is not commutative in R.

(3) (a ◦ b)oc = (aob) + 3c = (a + 3b) + 3c and ao(boc) = a + 3(boc) = a + 3(b + c) = a + 3b + 9c.

Since (aob)oc 6= ao(boc) for a, b, c ∈ R, o is not associative in R.

Example: 8. On Q define ∗ such that a ∗ b = ab + 1 for every a, b ∈ Q.

(1) Since ab +1 ∈ Q for every a, b ∈ Q then ∗ is a binary operation.

(2) Since a ∗ b = ab + 1 = ba + 1 = b ∗ a, then ∗ is commutative.

(3) ∀a, b, c ∈ Q, (a ∗ b) ∗ c = (ab + 1) ∗ c = (ab + 1)c + 1 = abc + c + 1and a ∗ (b ∗ c) = a ∗ (bc + 1) = a(bc + 1) + 1 = abc + a + 1

⇒ (a ∗ b) ∗ c 6= a ∗ (b ∗ c) ⇒ ∗ is not associative in Q.

Example: 9. On R − {−1} define o such that aob = \(\frac{a}{b+1} \)for every a, b ∈ R − {−1}.

(1) Since \(\frac{a}{b+1} \)∈ R − {−1} for every a, b ∈ R − {−1}, then o is a binaryoperation.

(2) Since aob = \(\frac{a}{b+1} \)and boa = \(\frac{b}{a+1} \)then aob ≠ boa and hence o is not commutative.

(3) ∀a, b, c ∈ R − {−1}, (aob)oc = \(\frac{a}{b+1} \)oc = =\(\frac{\frac{a}{b+1}}{c+1}\)and ao(boc) = ao \(\frac{b}{a+1} \)

⇒ 0 is not associative R − {−1}.

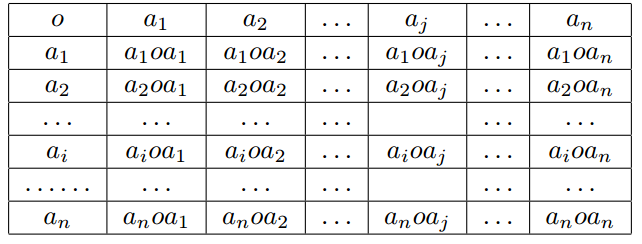

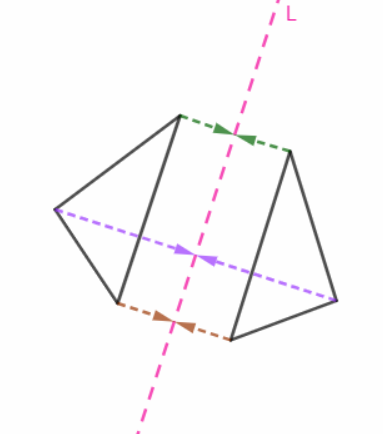

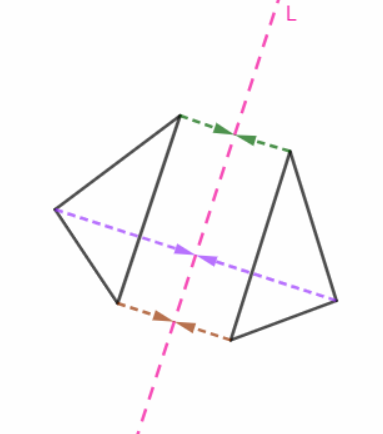

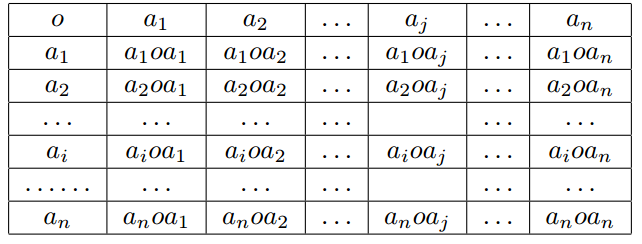

Composition table for an operation on finite sets (Cayley’s composition table) Sometimes an operation o on a finite set can conveniently be specified by a table called the composition table. The construction of the table is explained below.

Let S = {a1, a2, . . . ai, aj, . . . an} be a finite set with n elements. Let a table with (n + 1) rows and (n + 1) columns be taken. Let the squares in the first row be filled in with a, a1, a2, . . . an, and the squares in the first column be filled in with a, a1, a2, . . . an. Let ai(1 ≤ i ≤ n) and aj(1 ≤ j ≤ n) be any two elements of S.

Let the product aioaj. obtained by operating ai with aj be placed in the square which is at the intersection of the row headed by ai and the column headed by aj. Thus the following table be got.

From the composition table, we can infer the following laws.

(1) Closure law. If all the products formed in the table are the elements of s, the ’ o ’ is said to be a binary operation in S, and S is said to be closed under the composition ’ o ’.

Otherwise, o is not a binary operation in S and the set S is not closed under the operation o.

(2) Commutative law. If the elements in every row are identical with the corresponding elements in the corresponding column, then the composition o is said to be commutative in S. Otherwise, the binary operation o is not commutative in S.

(3) Associative law. Also, we can know from the table whether the binary operation follows associative law or not.

Note: The diagonal through a 1oa 1 and anoan is called the leading diagonal in the table. If the elements in the table are symmetric about the leading diagonal, then we infer that o is commutative in S.

Binary Operations Identity Element.

Definition. Let o be a binary operation on a non-empty set S. If there exists an element e ∈ S such that aoe = a = eoa ∀a ∈ A, then e is called Identity of S w.r.t. the operation o. If e is an identity of S w.r.t. o, then it can be proved to be unique.

Example: 1 In Z, 0 is the identity w.r.t. ’ + ’ since a + 0 = a = 0 + a, ∀a ∈ Z. But in N, 0 is not the idntity w.r.t. + since 0 ∈/ N and 1 is the identity w.r.t. ’ ’ as a · 1 = a = 1 · a∀a ∈ N.

Example: 2 In R, 0 is the identity w.r.t. + since a + 0 = a = 0 + a, ∀a ∈ R. In R, 1 is the identity w.r.t. ’!’ since a · 1 = a = 1 · a, ∀a ∈ R.

Note: Operations (−), (÷) are not binary operations in N. But +, −, · are binary operations in R and ÷ is a binary operation in R ∗ (non-zero real number set). Also o is the identity in R w.r.t. +, 1 is the identity in R (w.r.t. ’ · ’ where as ’ − ’ and 0 ÷ 0 ’ do not have identity element in R.)

Invertible element. Definition.

Let e be the identity element in S w.r.t. the binary operation o. An element a ∈ S is said to be invertible w.r.t. o, if there is an element b in S such that aob = e = boa and b is called inverse of a. If o is associative in S, then inverse of a is unique in S and is denoted by a− 1 or sometimes as 1/a if the operation is · and by −a if the operation is +.

Note

1. a ◦ a− 1 = a− 1oa = e and e− 1oe = eoe− 1 = e. Also a− 1− 1 = a.

2. In R, −a is the inverse w.r.t. ’ + ’ and 1/a(a 6= 0) is the inverse w.r.t. ’.’of a. For : a + (−a) = 0 = (−a) + a and a · a1 = 1 = a1 · a(a 6= 0)

3. −a is not the inverse of a in N w.r.t. + and a− 1 is not the inverse of a in N w.r.t. •.

Also a− 1 is the inverse of a in R. w.r.t. ’ ’ ’ and −a is the inverse of a. w.r.t. ’+.’ in R.

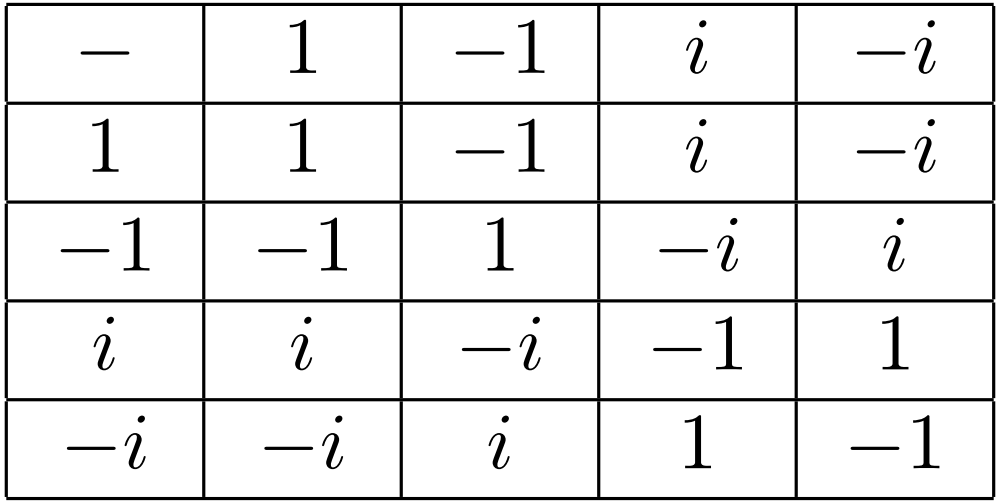

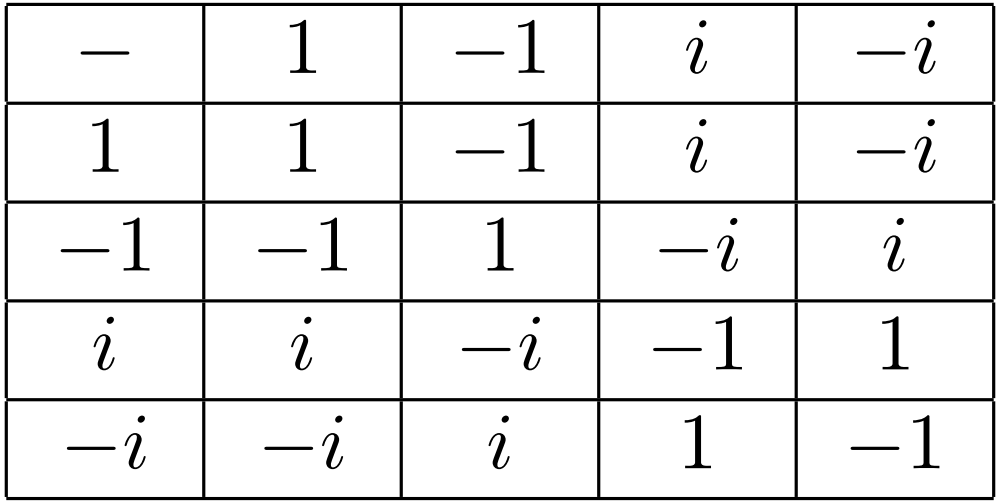

Example: 1. S = {1, −1, i, −i} and usual multiplication is the operation in S.

Then we have the following composition table. We can clearly see that is a binary operation in N following commutative law and associative law.

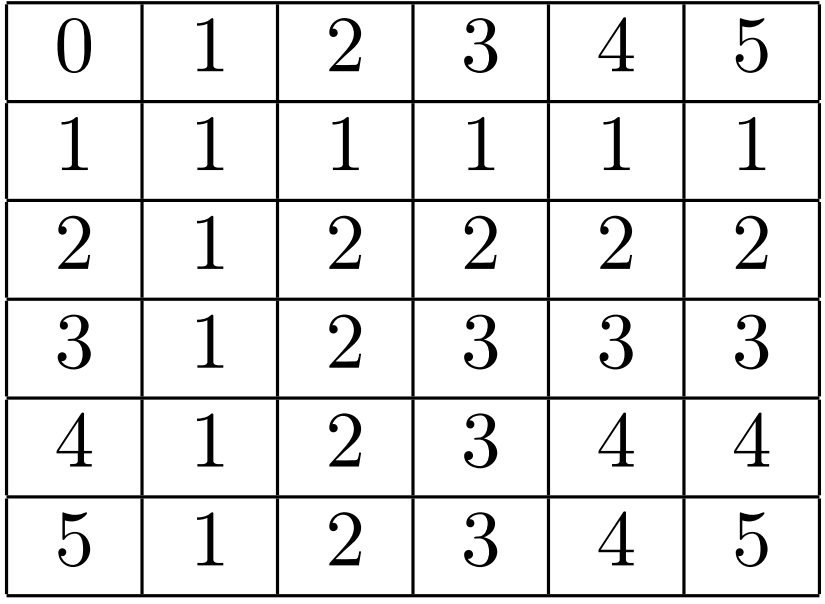

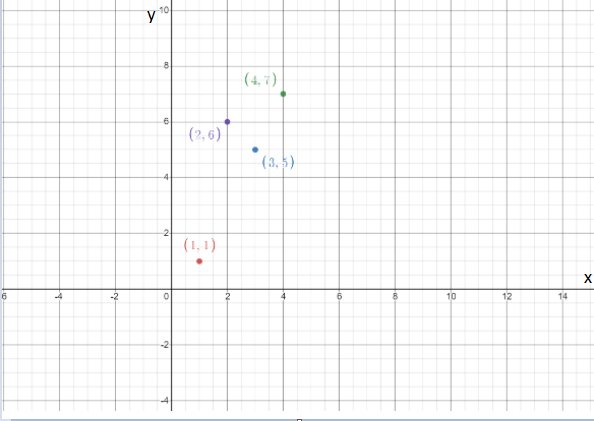

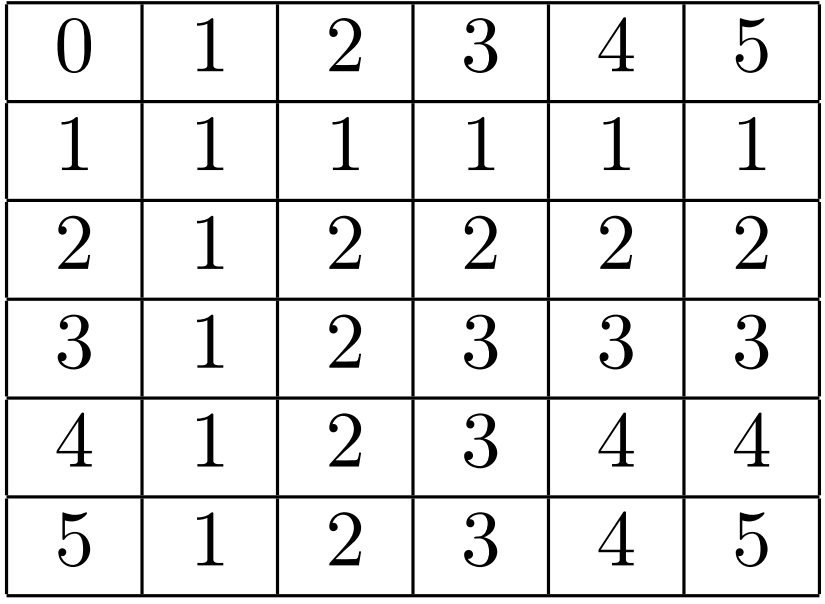

Example: 2. Consider the binary operation on the set {1, 2, 3, 4, 5} defined by aob = min{a, b}. Composition table is :

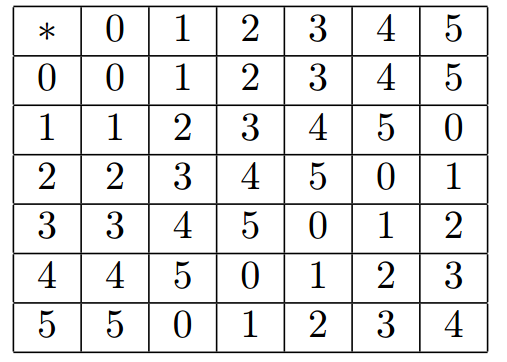

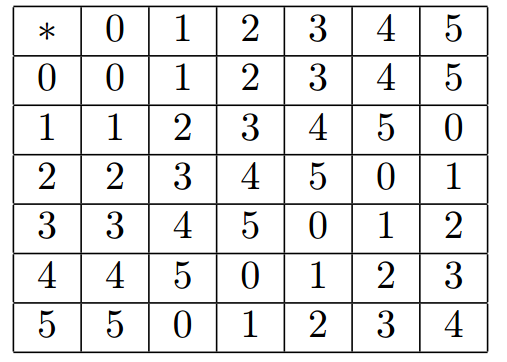

Example: 3. Define a binary operation ∗ on the set A = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5} as a ∗ b = � a + b, −if6a, +if ab <+ b6 ≥ 6 .0 is the identity w.r.t. ∗ and each element (a 6= 0) of the set is invertible with 6 − a being the inverse of a.

For: Composition table is :

(1) ∗ is binary since every entry belongs to A.

(2) Every row is same as the corresponding column ⇒ ∗ is commutative.

(3) Since every element of the first row = every corresponding element of the top row, the identity element exists and it is 0 .

since 0 ∗ 0 = 0, 0 ∗ 1 = 1, . . . ., 0 ∗ 5 = 5 and 0 ∗ 0, 1 ∗ 0 := 1, 2 ∗ 0 =2, . . . . . . . . . , 5 ∗ 0 = 5.

(4) Since 1 ∗ 5 = 0 = 5 ∗ 1, 1− 1 = 5 and 5− 1 = 1;

Since 2 ∗ 4 = 0 = 4 ∗ 2, 2− 1 = 4 and 4− 1 = 2;

Since 3 ∗ 3 = 0, 3− 1 = 3. Also 0− 1 = 0.

Solved Problems

Example: 1. (1) Show that the operation o given by aob = ab. is a binary operation. on the set of natural numbers N. Is this operation associative and commutative in N?

(2) a ∗ b = smaller of a and b (O.U.A12)

Solution. (1) N is the set of natural numbers and o is the operation defined in N such that aob = ab for a, b ∈ N. When a, b ∈ N, ab = a × a × . . . b times is also a natural number and hence ab ∈ N.

∴ o is binary operation in N. Let a, b, c ∈ N.

∴ (aob)oc = (aob)c = abc = abc and ao(boc) = aobc = abc

∴ (aob)oc 6= ao(boc) and o is not associative in N.

Since ab 6= ba i.e. ’ o0 is not commutative in N.

(2) a, b, c ∈ Z +. Now a ∗ b = smaller of a and b.

Suppose a < b. Then a ∗ b = a, and b ∗ a = a

⇒ a ∗ b = b ∗ a ⇒ ∗ is commutative.

Now suppose (a ∗ b) ∗ c = a ∗ c = a and

a ∗ (b ∗ c) = a ∗ b = a ⇒ (a ∗ b) ∗ c = a ∗ (b ∗ c)

⇒ ∗ is associative.

Example: 2. Let S be a non-empty set and o be an operation on S defined by aob = a for a, b ∈ S. Determine whether o is commutative and associative in S.

Solution. Since aob = a for a, b ∈ S and boa = b for a, b ∈ S, aob 6= boa.

∴ o is not commutative in S. Since (aob)oc = aoc = a

ao(boc) = aob = a for a, b, c ∈ S

∴ o is associative in S.

Example: 3. o is an operation defined on Z such that aob = a + b − ab for a, b ∈ Z. Is the operation, o a binary operation in Z ? If so, is it associative and commutative in Z?

Solution.

Given

o is an operation defined on Z such that aob = a + b − ab for a, b ∈ Z. Is the operation, o a binary operation in Z

If a, b ∈ Z we have a + b ∈ Z, ab ∈ Z

a + b − ab ∈ Z.

∴ aob = a + b − ab ∈ Z

∴ o is a binary operation in Z.

Since aob = a + b − ab = b + a − ba = boa, ’ o ’ is commutative in Z.

Now. (aob)ac = (aab) + c − (aob)c

= a + b − ab + c − (a + b − ab)c

= a + b − ab + c − ac − bc + abc and ao(boc) = a + (boc) − a(boc)

= a + b + c − bc − a(b + c − bc)

= a + b + c − bc − ab − ac + abc

= a + b − ab + c − ac − bc + abc

∴ (aabˆ )oc = ao(boc) and hence o is associative in Z.

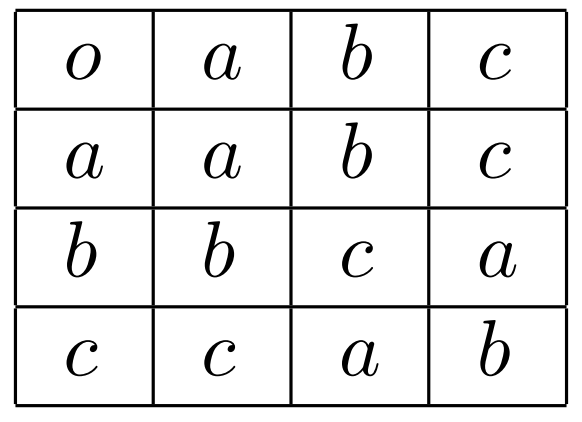

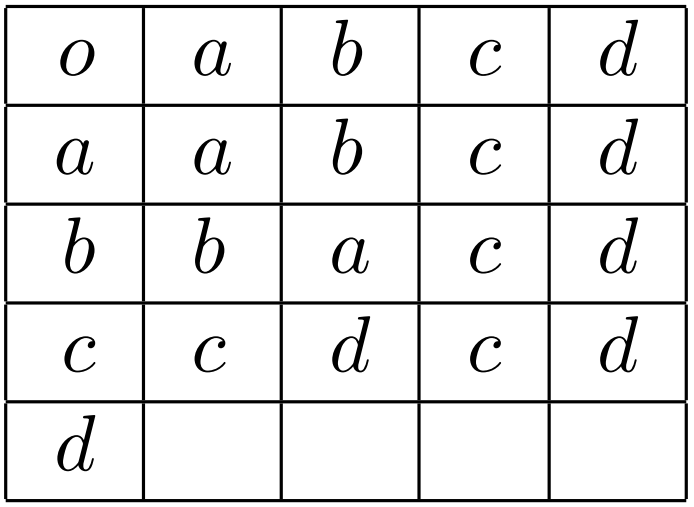

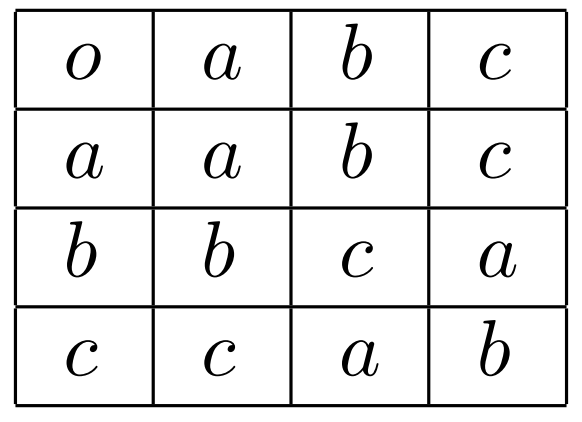

Example: 4. S = {a, b, c} and o is an operation on S for which the following composition table is formed. Is the operation o a binary operation in S ? Is the operation o in S commutative and associative?

Solution. All the products formed are the elements of S.

∴ o is a binary operation in S and hence S is closed under the operation o.

Since the elements in every row are identical with corresponding elements in the corresponding column, o is commutative in S.

Since (aob)oc = boc = a = aoa = ao(boc), (boa) oc = boc = bo(aoc) etc., o is associative in S.

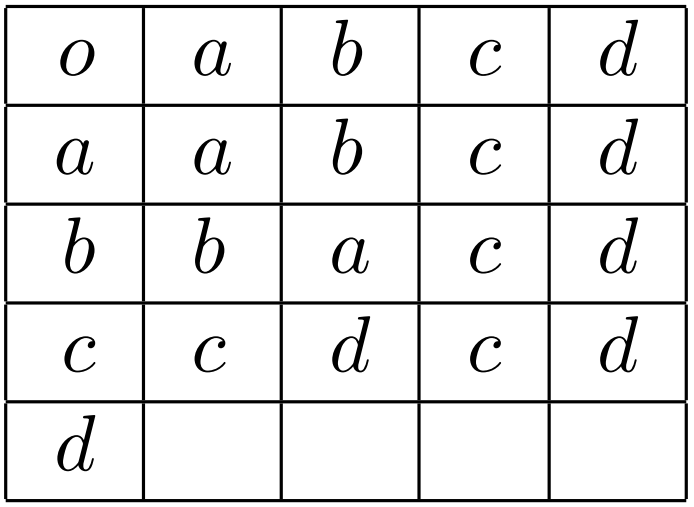

Example: 5. Fill in the blanks in the following composition table so that o is associative in S˙ = {a, b, c, d}

Solution.

Using associative law and by trial and error :

Since do(aoa) = doa and (doa)oa = do(aoa) = doa, doa must be equal to d only.

Since do(boa) = dob and (dob)oa = do(boa), dob must be equal to d only.

Since do(coa) = doc and (doc)oa = do(coa), doc must be equal to a only.

Since do(doa) = dod and do(doa) = (dod)oa, dod must be equal to a.

Thus d, d, a, a are respectively the four products.

Example: 6. Let P (S) be the power set of a non-empty set S. Let ’ ∩ ’ be an operation in P( S). Prove that associative law and commutative law are true for the operation ∩ in P(S) :

Solution.

Given

Let P (S) be the power set of a non-empty set S. Let ’ ∩ ’ be an operation in P( S).

P (S) = Set of all possible subsets of S.

Let A, B, C ∈ P(S). Since A ⊆ S, B ⊆ S ⇒ A ∩ B ⊆ S ⇒ A ∩ B ∈ P(S)

Also B ∩ A ⊆ S ⇒ B ∩ A ∈ P(S).

∴ ∩ is a binary operation in P(S).

Also A ∩ B = B ∩ A.

∴ ∩ is commutative in P(S).

Again A ∩ B, B ∩ C, (A ∩ B) ∩ C, and A ∩ (B ∩ C) are subsets of S.

∴ (A ∩ B) ∩ C, A ∩ (B ∩ C) ∈ P(S).

Since (A ∩ B) ∩ C = A ∩ (B ∩ C), ∩ is associative in P(S).

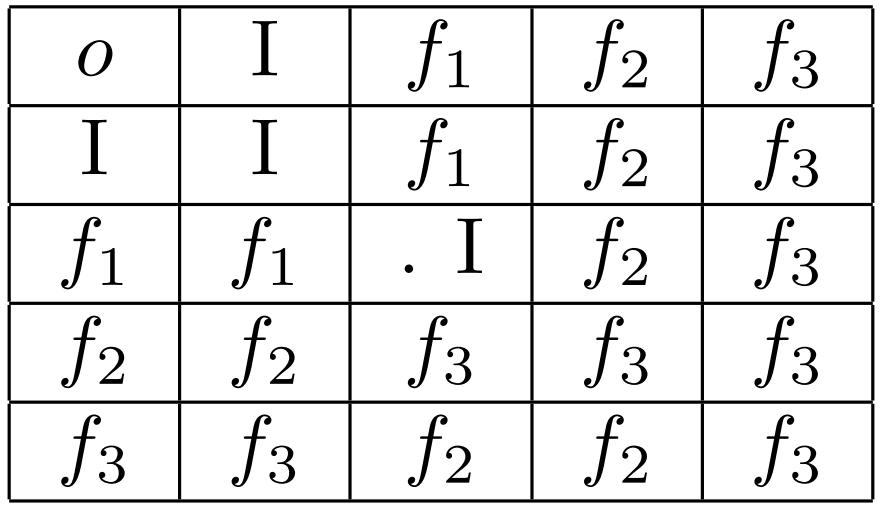

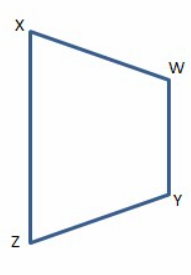

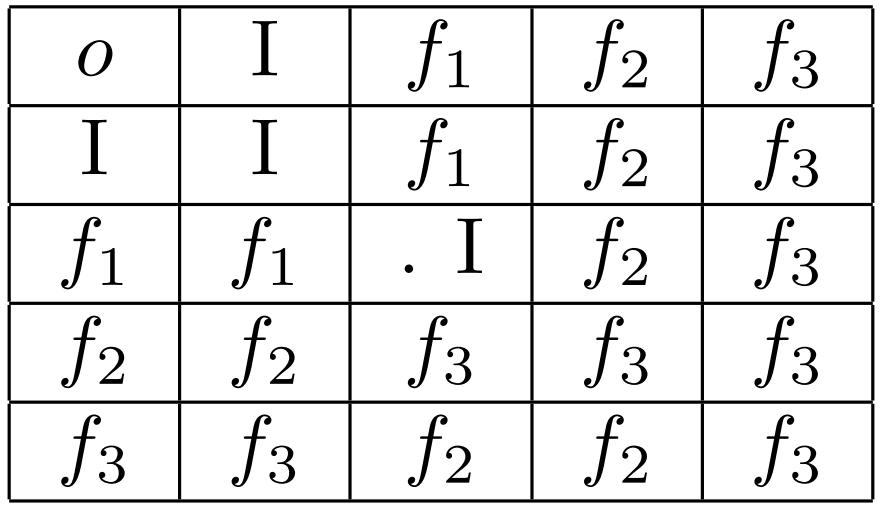

Example: 7. A = {a, b}. Consider the set S of all mappings from A → A. Is the composition of mappings denoted by o is a binary composition in S.

Solution.

Given

A = {a, b}. Consider the set S of all mappings from A → A.

Total number of possible mappings from A → A is 4.

Let them be I : A → A = {(a, a), (b, b)}

f1 : A → A = {(a, b), (b, a)}

f2 : A → A = {(a, a), (b, a)}

f3 : A → A = {(a, a), (b, b)}

∴ S = {I, f1, f2, f3}. Let the composition of mappings be denoted by o.

Composition table is :

Clearly (1) o is a binary operation in S,

(2) o is not commutative in S and

(3) o is not associative in S. sin a(f2of3) of 16= f2o (f3of1)