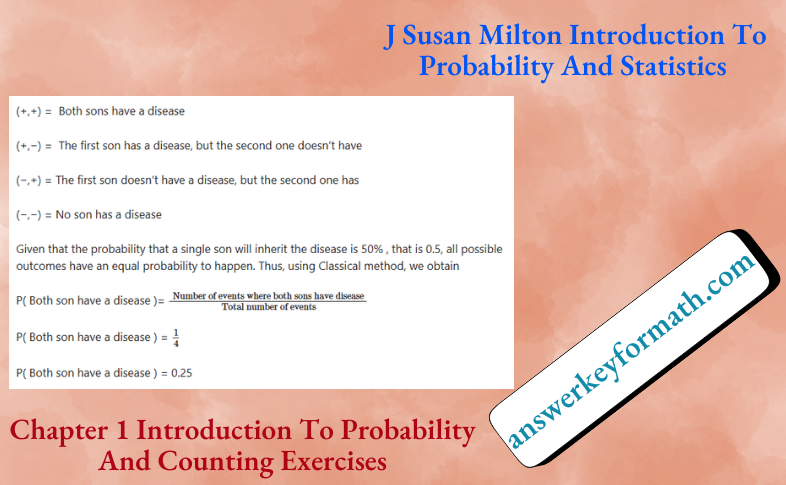

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Probability And Counting Exercises

- Chapter 2 Some Probability Laws Exercises

- Chapter 3 Discrete Distributions Exercises

- Chapter 4 Continuous Distributions Exercises

- Chapter 5 Joint Distributions Exercises

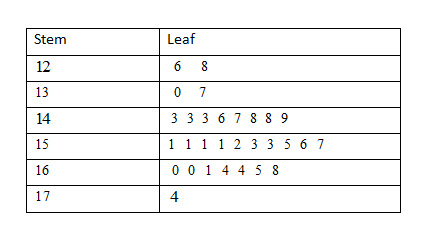

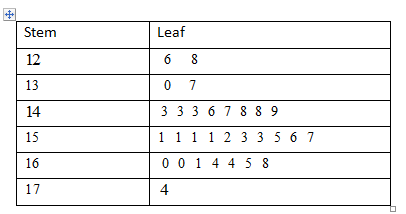

Introduction To Probability And Statistics Chapter 8 Exercises Solutions Page 263 Exercise 1 Problem 1

Given problem statement, when programming from a terminal, one random variable response time was recorded in seconds.

These data are tabled also a table was given.

Next draw the stem and leaf diagram and assume the normality is reasonable or not

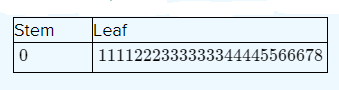

Stem and leaf plot response time N = 30

Leaf unit = 0.010

Therefore, the step plot shows the data is equally distributed on both sides. So, the assumptions of normality appear reasonable.

Read and Learn More J Susan Milton Introduction To Probability And Statistics Solutions

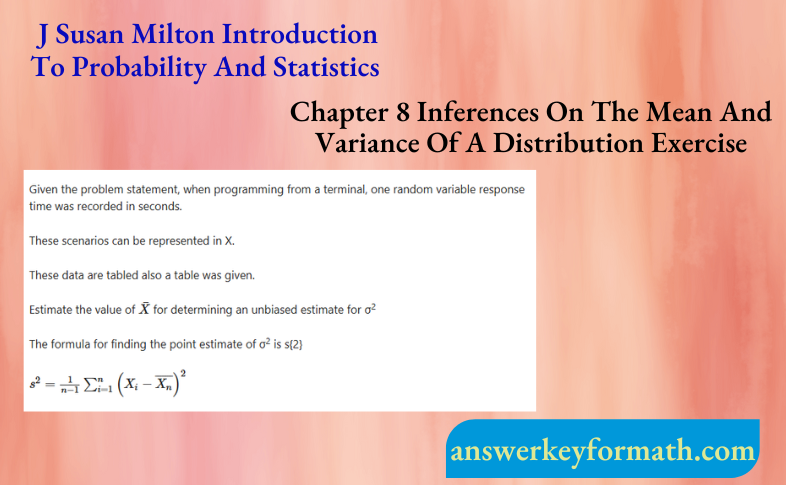

Given: When programming from a terminal, one random variable response time was recorded in seconds.

These scenarios can be represented in X.

n = 30

Determine the \(\bar{X}\) value

\(\overline{X_n}=\frac{\sum X_i}{n}\)

\(\bar{X}\)n = \(\left(\begin{array}{l}

1.48+1.26+1.52+1.56+1.48+1.46+1.30+1.28+ \\

1.43+1.43+1.55+1.57+1.51+1.53+1.68+1.37+ \\

1.47+1.61+1.49+1.43+1.64+1.51+1.60+1.65+ \\

1.60+1.64+1.51+1.51+1.53+1.74

\end{array} 30\right.\)

Therefore, an unbiased point estimate for σ2 is 0.0129

From previous problem the point estimate of σ2 is s2 was obtained and using this value to find a 95 confidence interval for σ2

First determine the value of α

α = 1 − confidence level

Given :

From previous problem the point estimate of σ2 is s2 = 0.0129

Find the value of α is

α = 1 − 95

α = 0.05

n = 30

Find a 95 confidence interval for σ2

Formula is , L1 ≤ σ2 L2

\(\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{\frac{\alpha}{2}}^2} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{1-\frac{\alpha}{2}}^2}\)

Using chi-square distribution table to find a probability value with corresponds to degrees of freedom.

Probability value0.025 that corresponds to 29 degrees of freedom is 45.7

Probability value 0.0975 that corresponds to 29 degrees of freedom is 16

Determine the confidence interval for σ2

\(\frac{(30-1)(0.0129)}{45.7} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{(30-1)(0.0129)}{16.0}\) \(\frac{0.3741}{45.7} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{0.3741}{16.0}\)

0.00082 ≤ σ2 0.0234

Hence, 95 confidence interval for σ2 is (0.0082,0.0234)

Therefore,95 confidence interval for σ2 is (0.0082,0.0234)

From previous problem the point estimate for σ2

Was obtained and using this value to find a 95 confidence interval for σ

First determine the value of α

α = 1 − confidence level

Given :

From previous problem the point estimate for σ2 is 0.0129

Find the value of α is α = 1−95

α = 0.05

n = 30

Find a 95 confidence interval for σ formula is

\(\sqrt{L_1} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{L_2}\)\(\sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{\frac{\alpha}{2}}^2}} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{1-\frac{\alpha}{2}}^2}}\)

Using chi-square distribution table to find a probability value with corresponds to degrees of freedom.

Probability value0.95 that corresponds to 29 ,degrees of freedom is 45.7

Probability value 0.025 that corresponds to 29 degrees of freedom is 16

Determine the confidence interval for σ

\(\sqrt{\frac{(30-1)(0.0129)}{45.7}} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{\frac{(30-1)(0.0129)}{16.0}}\)

\(\sqrt{0.0082} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{0.0234}\)

0.091 0.091 ≤ σ ≤0.153

Hence, 95 confidence interval for σ is (0.091,0.153)

Therefore, 95 confidence interval for σ is (0.091,0.153)

Given problem statement, highway engineers have found a sign at night and it depends on its surround luminance.

These scenarios can be represented in X.

These surround luminance data are tabled also a table was given.

Estimate the value of X

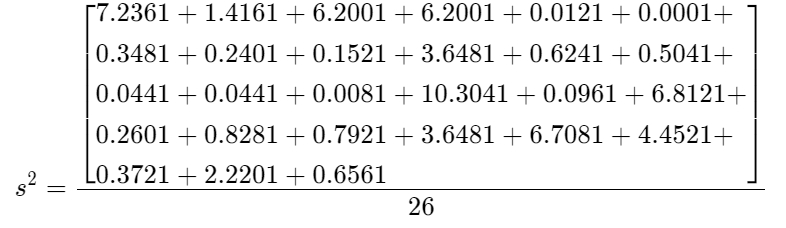

For determine an unbiased estimate for σ2

Formula for find the point estimate of σ2 is s2

s2 \(=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

Given : Highway engineers have found a sign at night and it depends on its surround luminance.

These scenario can be represented in X.

n = 30

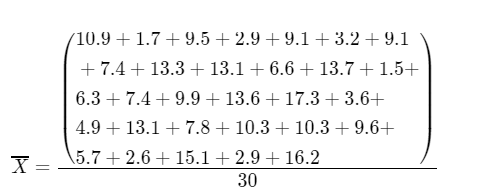

Determine the \(\bar{X}\) value

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{258.6}{30}\)

\(\bar{X}\) = 8.62

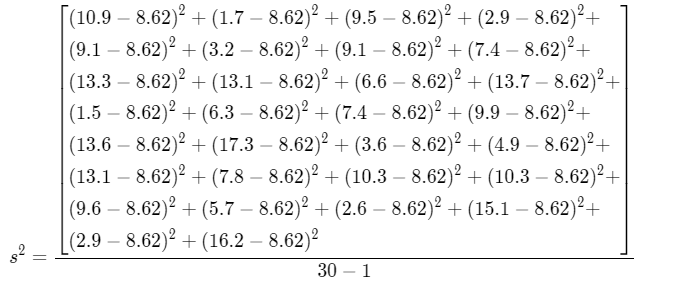

The point estimate for σ2 is

\(s^2=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

s2 = \(

\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

s2 = \(\frac{592.428}{29}\)

s2 = 20.428

Therefore, an unbiased point estimate for σ2 is, 20.428

From the previous problem the point estimate for σ2

was obtained and using this value to find a 90 confidence interval for σ.

First determine the value of α, α = 1− confidence level

Given :

From previous probelm the point estimate for σ2 is

20.428

Find the value of α is

α = 1 − 90

α = 0.10

n = 30

Find a 90 confidence interval for σ2

Formula is

L1 ≤ σ2 ≤ L2

\(\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{\frac{a}{2}}^2} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{1-\frac{a}{2}}^2}\)

Using chi-square distribution table to find a probability value with corresponds to degrees of freedom.

Probability value 0.05 that corresponds to 29 degrees of freedom is 42.557

Probability value 0.95 that corresponds to 29 degrees of freedom is 17.7084

Determine the confidence interval for σ2

\(\frac{(30-1)(20.428)}{42.557} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{(30-1)(20.428)}{17.7084}\)

\(\frac{5924.12}{42.557} \leq \sigma^2 \leq \frac{5924.12}{17.7084}\)

13.9204 ≤ σ2 ≤ 33.4537

Hence, 90 confidence interval for σ2 is (13.9204,33.4537)

Determine the confidence interval for σ

\(\sqrt{L_1} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{L_2}\) \(\sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{\frac{a}{2}}^2}} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{1-\frac{\alpha}{2}}^2}}\)\(\sqrt{13.9204} \leq \sigma \leq \sqrt{33.4537}\)

3.731 ≤ σ2 ≤ 5.784

Hence, 90 confidence interval for σ is (3.731,5.784)

Therefore, 90 confidence interval for σ is (3.731,5.784)

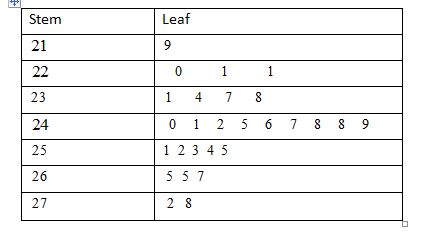

Given problem statement, Two voltage technique is used to analyze the crystals. Using electron microprobe to measure both quantitative and qualitative measurements.

These data are tabled also a table was given.

Next draw the stem and leaf diagram and assume the normality is reasonable or not.

Given :

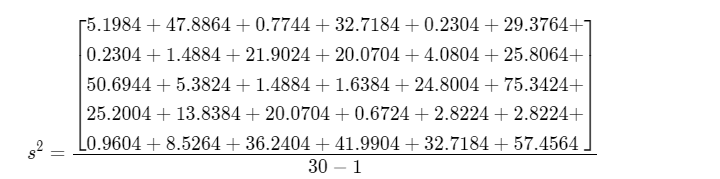

Stem and leaf plot measurement N = 27

The values have been multiplied by 100

Therefore, the step plot shows the data is equally distributed on both sides. So, the assumptions of normality appear reasonable.

Given problem statement, two voltage technique is used to analyze the crystals.

Using electron microprobe to measure both quantitative and qualitative measurements. These scenarios can be represented in X.

These data are tabled also a table was given.

Estimate the value of \(\bar{X}\) for determine an unbiased estimate for σ2

Formula for find the point estimate for σ2 is

\(s^2=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

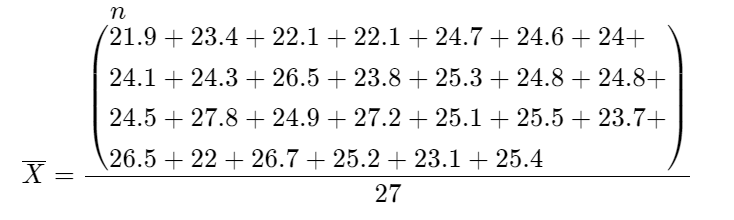

Given: Two voltage technique is used to analyze the crystals. Using electron microprobe to measure both quantiative and qualiitiative measurements.

These scenario can be represented in X.

n = 27

Determine the \(\bar{X}\) value

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{\sum X_i}{n}\)

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{663.9}{27}\)

\(\bar{X}\) = 24.59

The point estimate for σ2 is

\(s^2=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

s2 = \(\frac{63.8267}{26}\)

s2 = 2.455

Therefore, an unbiased point estimate for σ2 is, 2.455

Given problem statement, find the one-sided confidence interval for the upper bound.

Also, an interval in the form of [0,L].

Finally prove that the upper bound confidence interval

L = \(\frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\)

Given:

Find an interval in the form of P[σ2 ≤ L] = 1 − α

That means Confidence level = 1 − α

Form the diagram, the evidence is

Determine the confidence interval for σ2

P \(\left(\chi_{1-\alpha}^2 \leq \frac{(n-1) s^2}{\sigma^2}\right)\) = 1 − α

P \(\left(\sigma^2 \leq \frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\right)\) = 1 − α

Hence \(=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\)

Therefore, the confidence interval for upper bound is \(=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\) and its proved.

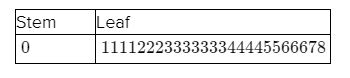

Given problem statement, Robotic technology was explained.

The Robots are used to apply adhesive to a specified location.

These location data are tabled also a table was given.

Next draw the stem and leaf diagram and assume the normality is reasonable or not.

Given :

Stem and leaf plot measurement N = 25

The values have been multiplied by 1000

Therefore, the step plot shows the data is equally distributed on both sides. So, the assumptions of normality appear reasonable.

Given problem statement, Robotic technology was explained.

The Robots are used to apply adhesive to a specified location. These scenarios can be represented in X.

These location data are tabled also a table was given.

Estimate the value of \(\bar{X}\) For determine an unbiased estimate for σ2

Formula for find the point estimate for σ2 is

\(s^2=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

Given : Robotic technology was explained.

The Robots are used to apply adhesive to a specified location.

These scenarios can be represented in X

n = 27

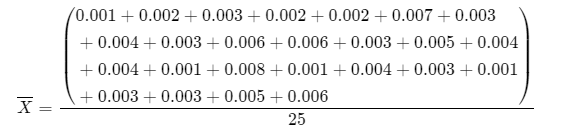

Determine the \(\bar{X}\) value

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{\sum X_i}{n}\)

\(\bar{X}\) =\(\frac{0.09}{25}\)

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.0036

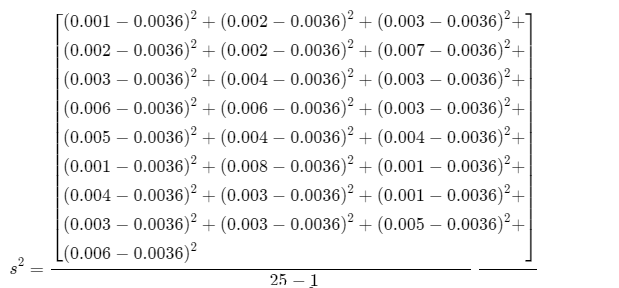

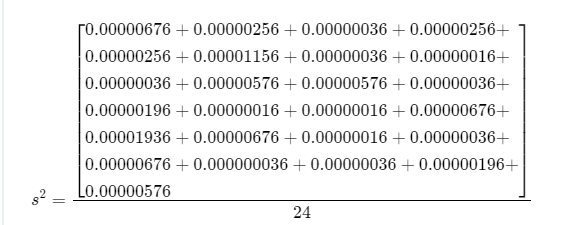

The point estimate for σ2 is

\(\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

s2 = \(\frac{0.00009}{24}\)

s2 = 0.00000375

Therefore, an unbiased point estimate for σ2 is, 0.00000375

Initially understand the theorems and using the theorem to prove that mean and variance values such as E[S2 ]= σ2 and Var S2

= \(\frac{2 \sigma^4}{(n-1)}\)

Show that X be a random variable. The mean and variance is

E[S2 ]= σ2

Var S2 = \(\frac{2 \sigma^4}{(n-1)}\)

From S2 is an unbiased estimator for σ2. Hence? E[S2] = σ2

From using of formula \(\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\sigma^2} \sim \chi_{(n-1)}\)

The variance of the chi squared distribution is n 2(n−1)

Now

Var [ \(\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\sigma^2}\)] = 2(n – 1)

\(\frac{(n-1)^2}{\sigma^4}\)Var S2 = 2(n – 1)

Var S2 = 2(n – 1)\(\frac{\sigma^4}{(n-1)^2}\)

Var s2 =\(\frac{2 \sigma^4}{(n-1)}\)

Therefore, X be a random variable then the mean and variance E[S2 ]= σ2,Var S2 \(\frac{2 \sigma^4}{(n-1)}\) and its proved.

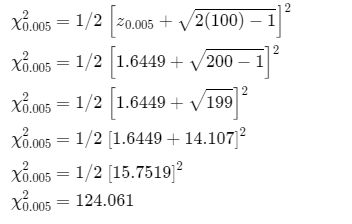

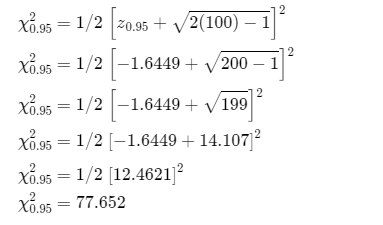

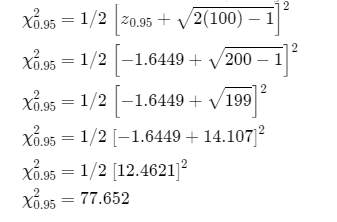

Given Samples: χ0.005 and χ0.95

Formula for find chi squared points: \(\chi_r{ }^2=1 / 2\left[z_r+\sqrt{2 \gamma-1}\right]^2\)

Using above formula to determine the approximate points of the given samples.

Given : χ0.005 and χ0.95

Formula for approximate the chi squared points \(\chi_r{ }^2=1 / 2\left[z_r+\sqrt{2 \gamma-1}\right]^2\)

r is significance level and γ is the degrees of freedom

Approximate the points for χ0.005

Approximate the points for χ0.95

Therefore, approximated points of χ0.005 and χ0.95 is 124.061 and 77.652

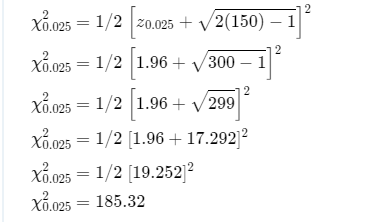

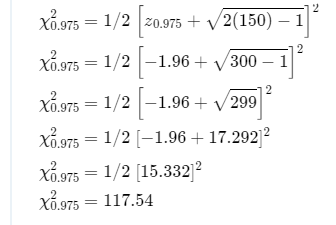

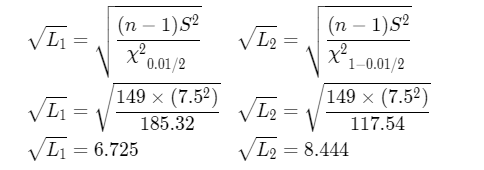

Given: Standard deviation value is s = 7.5 and sample size is n = 150

Using above values to find the confidence interval on deviation.

Formula for find the confidence interval for deviation

\(\sqrt{L_1}=\sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{\alpha / 2}^2}}\sqrt{L_2}=\sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha / 2}^2}}\)Given: Standard deviation and sample sizes are included below

s = 7.5

n = 150

Formula for find interval

\(\sqrt{L_1}=\sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{\alpha / 2}^2}} \sqrt{L_2}=\sqrt{\frac{(n-1) S^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha / 2}^2}}\)

Determine the interval for χ0.025

Determine the interval for χ0.025

Confidence interval is

Hence, 95 % confidence interval on the standard deviation is (6.725,8.444)

Therefore,95 % the confidence interval on the standard deviation is(6.725,8.444)

Given: Standard deviation value is s = 0.01 and sample size is n = 100

Using above values to find the confidence interval for deviation One sided confidence interval

\(L=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\)

Given : Standard deviation and sample size is

s = 0.01

n = 100

Formula for find interval

\(L=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\)

Chi squared points can be approximated by the formula

\(\chi_{1-r}^2=1 / 2\left[z_{1-r}+\sqrt{2 \gamma-1}\right]^2\)

Approximate the points for χ0.95

Determine the confidence interval

\(L=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{\chi_{1-\alpha}^2}\)\(\sqrt{L}=\sqrt{\frac{99 \times(0.01)^2}{77.652}}\)

= 0.0113

Hence, 95 % confidence interval on the standard deviation is (0,0.0113)

Therefore, 95 % confidence interval on the standard deviation is (0,0.0113)

Given: t.05 (γ = 8)

In T Distribution table, the cumulative probability values are given.

If find a critical value, look up the confidence interval in the bottom row of the table.

From T distribution table the row locates 8 and the column of P[Tr ≤ t] locate 0.95 which corresponds to the critical value is 1.8595

Hence, the value of t.05 (γ = 8) is 1.8595

Therefore, the value of t.05(γ = 8) is 1.8595

J. Susan Milton Chapter 8 Inferences On Mean And Variance Answers Page 266 Exercise 9 Problem 17

Given: t.95 (γ = 8)

In T Distribution table, the cumulative probability values are given.

If find a critical value, look up the confidence interval in the bottom row of the table.

From T distribution table the row locates 8 and the column of P[Tr ≤ t] locate 0.95 which corresponds to the critical value is −1.8595

Therefore, the value of t.95 (γ = 8) is−1.8595

Given: t 0.975 (γ = 12)

In T Distribution table, the cumulative probability values are given.

If find a critical value, look up the confidence interval in the bottom row of the table.

From T distribution table the row locates 12 and the column of P[Tr ≤ t] locate 0.975 which corresponds to the critical value is −2.1788

Hence, the value of t.975 (γ = 12) is −2.1788

Therefore, the value of t 975 (γ = 12) is −2.1788

Solutions To Inferences On Mean And Variance Exercises Chapter 8 Susan Milton Page 265 Exercise 10 Problem 19

In this given question, t value is .05.

In this given question, γ value is 50

Have to find a probability for given t value with given γ value.

Point degree of freedom and search for a given t value.

Given t value = .05.

γ = 50.

By using the t table, t⋅05 (γ = 50) = 1.6759

Hence, the probability of given t value ⋅05 with degree of freedom γ = 50 is 1.6759.

In this given question, t value is .025.

In this given question, y value is 75.

Have to find a probability for given t value with given γ value.

Point degree of freedom and search for a given t value.

Given t

value t = .025

γ = 75

By using the t table, t = .025

(γ = 75) = 1.9921

Hence, the probability of given t value .025 with degree of freedom γ = 75 is 1.9921

Chapter 8 Inferences on Mean and Variance examples and answers Susan Milton Page 265 Exercise 10 Problem 21

In this given question, t value is 0.1.

In this given question, γ value is 200.

Have to find a probability for given t value with given γ value.

Point degree of freedom and search for a given t value.

Given

t value = 0.1

γ = 200

By using the t table

t 0⋅1 (γ = 200) = 1.2858

Hence, the probability of given t value 0.1 with degree of freedom γ = 200 is 1.2858

In this question, the given data is \(\sum_{i=1}^{20} x_i\) = 25.792 and

\(\sum_{i=1}^{20} x_i^2\) = 33. 261596

Have to find \(\bar{X}\) , s2 , s

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{\sum x_i}{n}\)

s2 = \(\frac{1}{n-1}\left(\sum x_i^2-n(\bar{X})^2\right)\)

s = \(\sqrt{s^2}\)

Given

\(\sum_1^{15} x_i\) = 0.07

\(\sum_1^{15} x_i^2\) = 0.0489

n = 15

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{\sum x_i}{n}\)

\(\bar{X}\) = \(\frac{0.07}{15}\)

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.00467

\(\frac{1}{n-1}\left(\sum x_i^2-n(\bar{X})^2\right)\)

= \(\frac{1}{15-1}\left(0 \cdot 0489-15(0 \cdot 00467)^2\right)\)

= \(\frac{1}{14}(0 \cdot 0489-0 \cdot 000327)\)

= \(\frac{0.048573}{14}\)

= 0.0034695

s = \(\sqrt{s^2}\) = \(\sqrt{0.0034695}\)

s = 0.0589

Hence, the Value of \(\bar{X}\),s 2, s are 0⋅00467, 0⋅0034695,0⋅0589 respectively.

To find 95 % confidence interval 100(1 − α)

\(\bar{X} \pm t_{\frac{\alpha}{2}, \frac{n-1 s}{\sqrt{n}}}\) = 0.00467 \(\pm t_{0.05, \frac{15-10.0589}{\sqrt{5}}}\)

= 0⋅00467 ± 1.7693 × 0.0152

= 0.00467 ± 0.0269

= (0⋅00467 − 0.0269, 0.00467 + 0.0269)

= (−0.02223, 0.03157)

Hence,95 % confidence interval on the mean outside diameter of the pipes is(−0.02223,0.03157)

The makers of this pipe claim that the mean outside diameter is 1.29, so an average overestimate is 0.05.

The average overestimates the distance by 0.05 which is not reasonable.

Because the overestimates do not lie within 90 confidence interval.

Hence, the confident interval does not lead to suspect this responded.

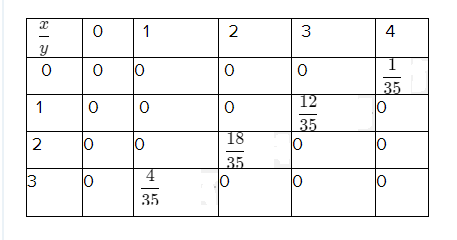

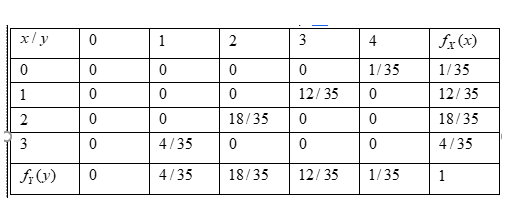

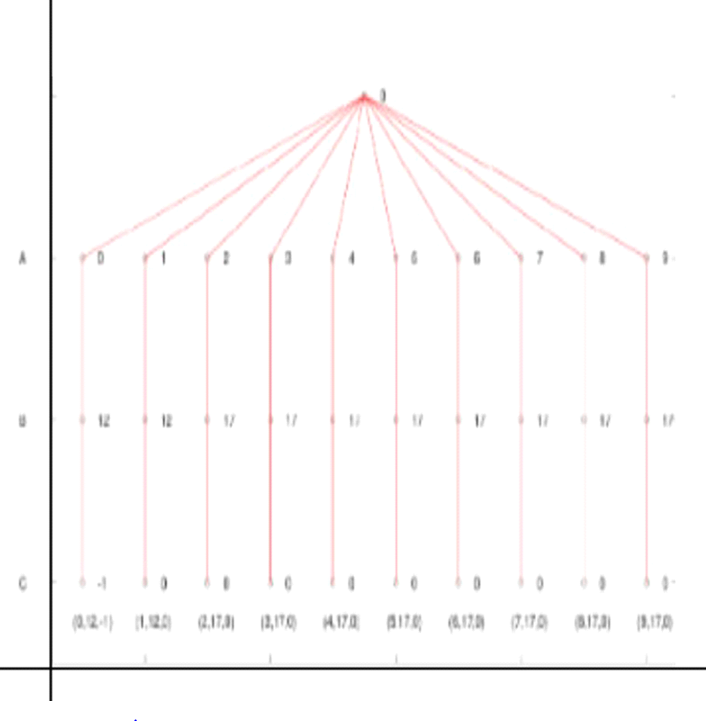

Introduction To Probability And Statistics Chapter 5 Exercises Solutions Page 169 Exercise 1 Problem 1

In Given problem, is a hypergeometric distribution.

Hypergeometric distribution: A random variable X has a hypergeometric distribution with parameters N,n and r if its density is given by

f(x) = \(\frac{\left(\begin{array}{l}

r \\

x

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}

N-r \\

n-x

\end{array}\right)}{\left(\begin{array}{l}

N \\

n

\end{array}\right)}\)

Max [0,n−(N−r)] ≤ x ≤ min(n,r)

Given table

Find the probability for hypergeometric function

Using given statement to get a required probability such as, N = 7,r = 3

P(X = x) = \(\frac{\left(\begin{array}{l}

r \\

x

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}

N-r \\

n-x

\end{array}\right)}{\left(\begin{array}{l}

N \\

n

\end{array}\right)}\)

Putx = 0 in above equation

P(X = x) = \(\frac{\left(\begin{array}{l}

3 \\

0

\end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{l}

7-3 \\

4-0

\end{array}\right)}{\left(\begin{array}{l}

7 \\

4

\end{array}\right)}\)

P(X = x) = \(\frac{1}{35}\)

Therefore, the probability for a hypergeometric function value is \(\frac{1}{35}\) and the table values are verified.

Read and Learn More J Susan Milton Introduction To Probability And Statistics Solutions

Hence, the marginal density was obtained and the variable Y is the Continuous Random Variable.

Therefore, the marginal density was obtained and the variable Y is the Continuous Random Variable.

J. Susan Milton Joint Distributions Chapter 5 Answers Page 169 Exercise 1 Problem 3

If two random variables are independent then it satisfies the following conditions,

1. P(x/y) = P(x)

2. P(x ∩ y) = P(x) ∗ P(y)

Also, the joint distribution of a function is fxy (x,y) = fx (x) fy(y)

Two random variables are independent, if the value of one variable does not change the probability value of another variable.

Therefore, If two random variables for independent then satisfies a condition 1. P(x∣y) = P(x) , 2. P(x∩y) = P(x)∗ P(y)

Given problem, fxy(x,y) = 1/n2

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition,\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\) = 1

The values of X and Y between

x = 1,2,3 ,…., n

y = 1,2,3, …., n

Given: fxy(x,y) = 1/n2

Find joint density function

\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)=\sum_{x=1}^n \sum_{y=1}^n \frac{1}{n^2}\)\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{1}{n^2} \sum_{x=1}^n \sum_{y=1}^n 1\)

\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{n}{n^2} \sum_{y=1}^n 1\)

\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{n}{n^2}(n)\)

\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\) = 1

Hence, a given function is discrete joint density function and the condition is satisfied.

Therefore, the function is a discrete joint density function and the condition x \(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\) = 1 is satisfied.

Solutions To Joint Distributions Exercises Chapter 5 Susan Milton Page 169 Exercise 2 Problem 5

Given problem, fxy(x,y) = 1/n2

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition,\(\sum_x \sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\)= 1

The values of X and Y between

x = 1,2,3, …., n

y = 1,2,3, …., n

Given: fxy(x,y)=1/n2

Find joint density function

Using given function to get a marginal density

Find the marginal density of X

\(f_X(x)=\sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\)\(f_X(x)=\sum_1^n \frac{1}{n^2}\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{1}{n^2} \sum^n 1\)

\(f_X(x)=\sum_1^n \frac{1}{n^2}\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{1}{n^2} \sum_1^n 1\)

Determine the marginal density of Y

\(f_Y(y)=\sum_1^n \frac{1}{n^2}\)

\(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n^2} \sum_1^n 1\)

\(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n^2}(n)\)

\(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n}\)

Therefore, the marginal densities of a given function both X and Y is \(\frac{1}{n}\)

If two random variables are independent then it satisfies the following conditions,

1. P(x∣y) = P(x)

2. P(x ∩ y) = P(x) ∗ P(y)

Also, the joint distribution of a function is

fxy(x,y) = fx(x) fy(y)

Two random variables are independent, if the value of one variable does not change the probability value of another variable.

Given problem,{{f}{XY}}(x,y) = 1/n2

The marginal densities of a given function both X

and Y is \(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n}\).

Hence, the values are independent.

Therefore, the given function marginal densities of both X and Y is \(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n}\) and independent.

Chapter 5 Joint Distributions Examples And Answers Susan Milton Page 169 Exercise 3 Problem 7

Given problem ,fxy(x,y) = 2/n(n+1)

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition \(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n}\).

The values of X and Y between

x = 1,2,3,….,n

y = 1,2,3,….,n

Given: fxy (x,y) = 2/n(n + 1)

Find joint density function

\(\sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n f_{X Y}(x, y)=\sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n \frac{2}{n(n+1)}\)\(\sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{2}{n(n+1)} \sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n \)

Sum of first n integers is given by \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2}\)

\(\sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{2}{n(n+1)} \times \frac{n(n+1)}{2}\)

\(\sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n f_{X Y}(x, y)\) = 1

Hence, a given function is discrete joint density function and the condition is satisfied.

Therefore, the function is a discrete joint density function and the condition \(\sum_{y=1}^n \sum_{x=1}^n f_{X Y}(x, y)\)= 1 is satisfied.

Given problem, fxy (x,y) = 2/n(n + 1)

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition \(f_Y(y)=\frac{1}{n}\).

The values of X and Y between

x = 1,2,3,….,n

y = 1,2,3,….,n

Using given function to get a marginal density

Find the marginal density of X,

\(f_X(x)=\sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\)\(f_X(x)=\sum_{y=1}^n \frac{2}{n(n+1)}\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{n(n+1)} \sum_{y=1}^n 1\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{n(n+1)}(n)\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{(n+1)}\)

Determine the marginal density of Y

\(f_X(x)=\sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\)\(f_X(x)=\sum_{y=1}^n \frac{2}{n(n+1)}\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{n(n+1)} \sum_{y=1}^n 1\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{n(n+1)}(n)\)

\(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{(n+1)}\)

Therefore, the marginal densities of a given function both X and Y \(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{(n+1)}\)

If two random variables are independent then it satisfies the following conditions,

1. P(x∣y) = P(x)

2. P(x∩y) = P(x) ∗ P(y)

Also, the joint distribution of a function is

fxy(x,y) = fx(x) fy(y)

Two random variables are independent, if the value of one variable does not change the probability value of another variable.

Given problem, fxy (x,y) = 2/n(n + 1)

The marginal densities of a given function both X and Y is \(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{(n+1)}\)

Hence, the values are independent.

Therefore, the given function marginal densities of both X and Y is \(f_X(x)=\frac{2}{(n+1)}\) and its independent.

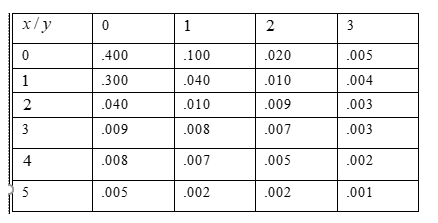

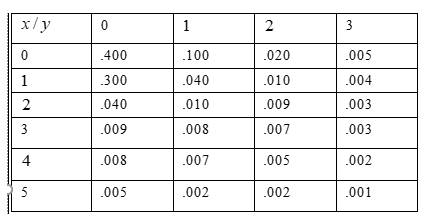

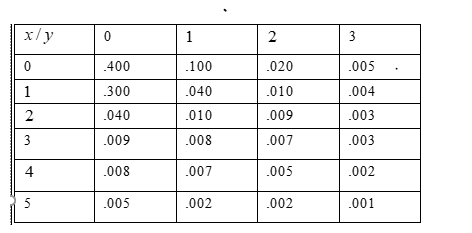

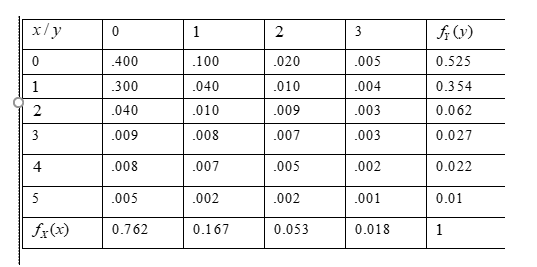

Probability And Statistics J. Susan Milton Chapter 5 Solved Step-By-Step Page 170 Exercise 4 Problem 10

In Given table,X represents the number of syntax errors and Y represents the number of errors in logic.

Problem statement: Determine the probability for selected program have neither of these errors.

Given table

In above table,X represents the number of syntax errors and Y represents the number of errors in logic.

Find the probability

Using given statement to get a required probability such as, p(x = 0,y = 0)

Hence, the value of p(x = 0,y = 0) is 0.4

Hence, the probability that selected program have neither these types of errors as 0.4

Therefore, the probability that selected program have neither these types of errors as 0.4

In Given table,X represents the number of syntax errors and Y represents the number of errors in logic.

Problem statement: Determine the probability for selected program at least one syntax error and at most one error in logic.

Given table,In above table,X represents the number of syntax errors and Y

Find the probability

Using given statement to get a required probability such as,

P[X ≥ 1 and Y ≤ 1]

P[X ≥ 1and Y ≤ 1]

[P(X = 1,Y = 0) + P(X = 2,Y = 0) + P(X = 3,Y = 0)

+ P(X = 4,Y = 0) + P(X = 5,Y = 0) + P(X = 1,Y = 1)

+ P(X = 1,Y = 2) + P(X = 1,Y = 3) + P(X = 1,Y = 4)

+ P(X = 1,Y = 5)]

P[X ≥ 1and Y ≤ 1] = 0.300 + 0.040 + 0.009 + 0.008 + 0.005 + 0.040 + 0.010+ 0.008 + 0.007 + 0.002

P[X ≥ 1and Y ≤ 1] = 0.429

Hence, the probability for selected at least one syntax error and at most one error in logic is 0.429

Therefore, the probability for selected at least one syntax error and at most one error in logic is 0.429

Using given table values for determine the marginal density of the function.

If two random variables with joint density fXY then the marginal density for X denoted as fx given by

\(f_X(x)=\sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\)

The mariginal density for y denoted as

\(f_Y(y)=\sum_y f_{X Y}(x, y)\)

Given table

In above table, X represents the number of syntax errors and y represents the number of errors in logic.

Using Given table, sum all values for determine a marginal density

Hence, the marginal density was obtained

Therefore, the marginal density for both values are obtained in above table.

On previous example to get a function is, fxy(x,y)= \(\frac{1.72}{x}\)

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition

\(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d x d y=1\)

The values of $X$ and $Y$ between 27 ≤ y ≤ x ≤ 33

Given: \(f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{1.72}{x}\)

Use continuous joint density function to find the value of P[X ≤ 30 and Y ≤ 28]

P[X ≤ 30 and Y≤ 28]= \(\int_{27}^{30} \int_{27}^{28} f_{X Y}(x, y) d x d y\)

\(=\int_{27}^{30} \int_{27}^{28} \frac{1.72}{x} d x d y\)

Integrate depends on y and apply the limit values in given function

\( = 1.72 \int_{27}^{30} \frac{1}{x}[y]_{27}^{28} d x\)

\( = 1.72 \int_{27}^{30} \frac{1}{x} d x\)

Integrate depends on x and apply the limit values in given function

P[X ≤ 30 and Y≤28] = 1.72× \([\ln x]_{27}^{30}\)

P[X ≤ 30 and Y≤28] = 1.72(3.4012 − 3.2958)

P[X ≤ 30 and Y≤28] = 0.1813

Therefore, using previous example to find a function as fxy (x,y)= \(\frac{1.72x}{x}\) and the value of P[X ≤ 30 and Y ≤ 28] is 0.1813.

On previous example to get a function is,f xy(x,y) = \(\frac{c}{x}\)

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition \(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d x d y\) = 1

The values of X and Y between 27 ≤ y ≤ x ≤ 33

Given: fxy (x,y) = \(\frac{c}{x}\)

Use continuous joint density function to find the value of c

\(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d y d x\) = 1

\(\int_{27}^{33} \int_{27}^x \frac{c}{x} d y d x\)= 1

Integrate depends on y and apply the limit values in given function

\(\int_{27}^{33}\left(\frac{c}{x} y\right)_{27}^x d x\) = 1

\(\int_{27}^{33}\left(c-\frac{c}{x}(27)\right) d x\) = 1

Integrate depends on x and apply the limit values in given function

\(\int_{27}^{33} c d x-27 \int_{27}^{33} \frac{c}{x} d x\)= 1

6c − 27c (ln(33)−3ln(3)) = 1

6c − 5.4181c = 1

c = \(\frac{1}{0.5819}\)

c = 1.72

Therefore, using previous example to find a function as f XY(x,y) = \(\frac{1.72}{x}\)with 27 ≤ y ≤ x ≤ 33 and the value of c is 1.72

Online Help For J. Susan Milton Joint Distributions Chapter 5 Exercises Page 170 Exercise 6 Problem 15

On previous example to get a function is \(f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{1.72}{x}\)

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition, \(f_X(x)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d y\) 27 ≤ y ≤ x ≤ 33

Given: \(f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{1.72}{x}\)

Using given function to get a marginal density

Find the marginal density of X

\(f_X(x)=\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d y\) \(f_X(x)=\int_{27}^{28} \frac{1.72}{x} d y\)

Integrate depends on Y and apply the limit values in given function

\(f_X(x)=1.72\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)[y]_{27}^{28}\)

\(f_X(x)=1.72\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)[28-27]\)

\(f_X(x)=1.72\left(\frac{1}{x}\right)\)

Therefore, Therefore, the marginal density for X and the value of P[X≤28] is \(f_{X Y}(x, y)=\frac{1.72}{x}\)

Given problem, fxy (x,y) = c(4x + 2y + 1)

If determine a function has to be joint density function satisfies the below condition

\(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d x d y\) = 1

The values of X and Y between

0 ≤ x ≤ 40

0 ≤ y ≤ 2

Given: fxy (x,y) = c(4x + 2y + 1)

Use continuous joint density function to find the value of c

\(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} f_{X Y}(x, y) d x d y\) = 1

\(\int_0^{40} \int_0^2 c(4 x+2 y+1) d x d y\) = 1

Integrate depends on y and apply the limit values in given function

\(c \int_0^{40}\left(4 x y+2 \frac{y^2}{2}+y\right)_0^2 d x\) = 1

\(c \int_0^{40}\left(4 x(2)+(2)^2+2\right) d x=\) 1

Integrate depends on x and apply the limit values in given function,

\(c \int_0^{40}(8 x+6) d x\)= 1

\(c\left(\frac{8 x^2}{2}+6 x\right)_0^{40}\)= 1

\(c\left(\frac{8(40)^2}{2}+6(40)\right)\)= 1

6640c = 1

c = \(\frac{1}{6640}\)

Therefore, the given function fXY (x,y)=c(4x+2y+1) and the value of c is \(\frac{1}{6640}\)= 1

Step-By-Step Guide To Joint Distributions Exercises Chapter 5 Milton Page 170 Exercise 7 Problem 17

To solve this, we need to integrate the PDF where X and Y defined as follow.

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1)

20 < x ≤ 0,1 ≤ y ≤ 2

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) = 1 \(\int_1^2 \int_{20}^{40} \frac{1}{6640}(4 x+2 y+1) d x d y\)

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) = \(\frac{1}{6640} \int_1^2\left(\frac{4 x^2}{2}+2 y x+x\right) \int_{20}^{40} d y\)

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) = \(\frac{1}{6640} \int_1^2(40 y+2420) d y\)

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) = \(\frac{1}{6640} \int_1^2(40 y+2420) d y\)

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) = \(=\frac{1}{6640}(2480)\)

P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) = \(\frac{38}{83}\)

The probability of temperature is P(x > 20,y ≥ 1) =\(\frac{38}{83}\)

Note that the integral of a valid joint density is equal to 1.

To verify joint density for a two-dimensional random variable.

f xy (x,y) = \([\frac{1}{x}\),o < y < x < 1

That the integral of a valid joint density is equal to 1.

1= \(1\iint_R f_{X, Y}(x, y), o<y<x<1\)

= \(\int_0^1 \int_0^x \frac{1}{x} d y d x\)

= \(\left.\int_0^1\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)\right|_0 ^x d x\)

= \(\left.(x)\right|_0 ^1\)

1 = 1

It is a joint density variable.

Exercise Solutions For Chapter 5 Susan Milton Joint Distributions Page 171 Exercise 8 Problem 19

We can get the probability by integrating it into the following regions.

To find P(X ≤ 0.5 and Y ≤ 0.25)

We can get the probability by integrating it on the following regions

0 < y ≤ 0.25

0.25≤ x < 0.5

Thus, we get that

P(X ≤ 0.5 and Y ≤ 0.25) = \(\int_{0.25}^{0.5} \int_0^{0.25} \frac{1}{x} d y d x\)

P(X ≤ 0.5 and Y ≤ 0.25) = \(\left.\int_{0.25}^{0.5}\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)\right|_0 ^{0.25} d x\)

P(X ≤ 0.5 and Y ≤ 0.25) = \(\left.0.25[\ln (x)]\right|_0 ^{0.25}\)

P(X ≤ 0.5 and Y ≤ 0.25) = 0.25 [(ln(0.5)] − [ln(0.25)]

P(X ≤ 0.5 and Y ≤ 0.25) = 0.1733

Hence, we have found the answer for P(X ≤ 0.5and Y ≤ 0.25) = 0.1733

The marginal density distribution of a subset of a collection of random variables is the probability distribution.

To find the marginal densities for X and Y.

\(f_{X, Y}(x, y) = \frac{x^2 y^2}{16}, 0 \leq x, y \leq 2\)

To calculate the marginal density for X, by definition, we have to calculate the integral

\(\left.f_X(x)=\int \mathbb{r} f_{(} X, Y\right)(x, y) d y\)

By plugging in the values where y is defined and the expression for joint density function, we obtain.

\(f_X(x)=\int_0^2 \frac{x^3 y^3}{16} d y=\frac{x^3}{64}(16-0)=\frac{x^3}{4}\), 0 ≤ x ≤ 2

To calculate the marginal density for Y, by definition, we have to calculate the integral

\(\left.f_Y(y)=\int \mathbb{r} f_{(} X, Y\right)(x, y) d x\)

By plugging in the values where y is defined and the expression for joint density function, we obtain.

\(f_X(x)=\int_0^2 \frac{x^3 y^3}{16} d y\)

\(=\frac{x^3}{64}(16-0)\)

\(=\frac{x^3}{4}\), 0 ≤ x ≤ 2

\(\frac{x^3}{4}\) 0 ≤ x ≤ 2

\(\frac{x^3}{4}\) 0 ≤ x ≤ 2

⇒ \(f_Y(y)=\frac{y^3}{4}, 0 \leq y \leq 2\)

The marginal density distribution of a subset of a collection of a random variables is the probability distribution.

To explain if X and Y are independent?

To check if X and Y are independent, we can simply check whether or not the following equation is fulfilled.

fx,y(x,y) = fx(x) fy(y)

By substituting the calculated expression , we obtain

\(f_{X, Y}(x, y)=\frac{x^3 y^3}{16}=\frac{x^3}{4} \frac{y^3}{4}=f_X(x) f_Y(y)\)

Hence X and Y are indeed independent.

Hence X and Y are indeed independent.

Page 171 Exercise 9 Problem 22

The marginal density distribution of a subset of a collection of random variables is the probability distribution.

To find P(X ≤ 1)

To find the probability P(X≤1), by definition, we have to calculate integral

P(X≤1) \(=\int_{-\infty}^1 f_X(x) d x\)

By substituting the given expression for the marginal density function and the values where x is defined, we proceed to calculate

P(X ≤ 1) \(\left.=\int_0^{\frac{x 3}{4}} d x=\frac{1}{16}-(1-0)=\frac{(}{1}\right)(16)\)

Therefore, the joint density for (X,Y) is given by \(\frac{1}{6}\)

fx,y(x,y) = c, 20 < x < y < 40 The integral of the PDF should always be equal to l, where x and y is defined.

Thus we get

\(=\iint_R f_{X, Y}(x, y) d x d y\)

\(=\int_{20}^{40} \int_{20}^y c d x d y\)

\(=c \int_{20}^{40}(y-20) d y\)

= c (200)

= c\(\frac{1}{200}\)

The value of c is c\(\frac{1}{200}\)

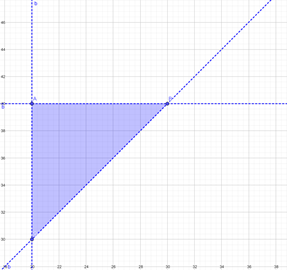

Page 171 Exercise 10 Problem 24

The integral of the PDF should always be equal to l, where x and y are defined, then integrating the PDF.

To find the probability that the carrier will pay at least $25 per barrel and the refinery will pay at most $30 per barrel for the oil.

We can express the problem

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30)

By integrating the PDF, we get that

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30\(=\int_{30}^{40} \int_{25}^y \frac{1}{200} d x d y\)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30) = \(\frac{1}{200} \int_{30}^{40}(y-25) d y\)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30)= \(\left.\frac{1}{200}\left(\frac{y^2}{2}-25 y\right)\right|_{30} ^{40}\)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30)= \(\left.\frac{1}{200}\left(\frac{y^2}{2}-25 y\right)\right|_{30} ^{40}\)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30)= \(\frac{1}{200}\)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30)= \(\frac{1}{2}\)

P(X ≥ 25 and Y ≥ 30) = \(\frac{1}{2}\)

The integral of the PDF should always be equal to l, where x and y are defined, then integrating the PDF.

To find the probability that the price paid by the refinery exceeds that of the carrier by at least $10 per barrel.

We can express the problem

P(Y > X + 10)

Now if we graph the domain, we get

Where

Point A = (20,40)

Point B = (30,40)

Point C = (20,30)

CB = y − 10

By integrating the PDF

P(Y>X+10)= \(\int_{30}^{40} \int_{25}^y \frac{1}{200} d x d y\)

\(=\frac{1}{200} \int_{30}^{40}(y-10-20) d y\)

\(=\frac{1}{200} \int_{30}^{40}(y-30) d y\)

\(=\left.\frac{1}{200}\left(\frac{y^2}{2}-30 y\right)\right|_{30} ^{40}\)

= \(\frac{50}{200}\)

= 0.25

The probablity is P(Y > X + 10) = 0.25

From Continuous Joint density we get that the three properties and identify a function as a density (X1,X2,X3,….. .Xn) f X1, X2, X3 ,. ….. Xn(x1,x2,x3, ….. .x1 )≥0]−∞<Xi< ∞

For all Xi where i is from 1 to n

\(\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \cdots \cdots \int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\) f X1, X2, X3 ,…… X1 (x1 ,x2,x3,……x1 ) dx1 dx2 dx3……..

P[a ≤ X1 ≤ b,c ≤ X ≤ d,e ≤ X3 ≤ f,…..,g ≤ X1 ≤ h

\(\int_a^b \int_c^d \int_e^f \cdots \cdots \int_g^h\) f X1, X2, X3 ,…… X(x1,x2,x3,……xn) dx1dx2 dx3 ………..;. Where a, b, c, …., h are real

Hence, a, b, c, …., h is called the joint density for (X1 ,X2,X3,…..,Xn)

Introduction To Probability And Statistics Chapter 7 Exercises Solutions Page 221 Exercise 1 Problem 1

Given problem, X1,X2,X3 ,…..,X20

In the given information, the population mean μ and variance σ were given.

Using the given values to find the sample mean and variance value.

Given: The population mean(μ)is 8 and the variance (σ)is 5.

Determine the mean of \((\bar{X})\)

The sample mean \((\bar{X})\) is an unbiased estimator of the population mean(μ)

The mean \((\bar{X})\) of the sample m X1,X2,X3 ,…..,X20 is the population mean.

Hence, the sample mean value is \((\bar{X})\) = 8

Determine the variance of \((\bar{X})\)

var \((\bar{X})\) = \(\frac{\sigma^2}{n}\)

Substitute n = 20 and σ2 = 5 in previous term

Var \((\bar{X})\) = \(\frac{5}{20}\)= 0.25

Therefore, the mean and variance of \((\bar{X})\) is Mean: 8 Variance: 0.25

Read and Learn More J Susan Milton Introduction To Probability And Statistics Solutions

Therefore, an unbiased estimator for the given parameter λs is X. X is the unbiased estimator of λs

Given problem statement, X is the number of paint defects in a square yard section of car body painted by robot.

A random sample from Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Poisson distribution: P(X = x) = \(\frac{e^{-\lambda}(\lambda)^x}{x !}\)

Given : The random variable X is the number of paint defects in a square yard section of car body painted by robot.

Also X is the Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Find the unbiased estimate for λs

Hence, the sample mean is the unbiased estimator of the population mean.

Then the estimator is

\(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\) ,\(\widehat{\lambda s}=\bar{X}\)

Therefore, an unbiased estimator for λs \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\) ,\(\widehat{\lambda s}=\bar{X}\)

J. Susan Milton Estimation Chapter 7 Descriptive Distributions Answers Page 221 Exercise 3 Problem 4

Given problem statement,X is the number of paint defects in a square yard section of car body painted by robot.

A random sample from Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square yard.

Given: The random variable X is the number of paint defects in a square yard section of car body painted by robot.

Also X is the Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Find the unbiased estimate for λs

Hence, the sample mean is the unbiased estimator of the population mean. Then the estimator is

\(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\), \(\widehat{\lambda s}=\bar{X}\)

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square yard is

ΣiXi = 8 + 0 + 2 + 5 + 3 + 7 + 0 + 1 + 9 + 10 + 12 + 6 = 63

λ8 = \(\frac{63}{12}\)

λ8 = 5.25

Therefore, the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square yard is, 5.25

Given problem statement,X is the number of paint defects in a square yard section of car body painted by robot.

A random sample from Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square foot.

Initally,Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square yard is

ΣiXi = 8 + 0 + 2 + 5 + 3 + 7 + 0 + 1 + 9 + 10 + 12 + 6 = 63

λ8 = \(\frac{63}{12}\)

λ8 = 5.25

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square foot is

One yard = Three feet

Hence, unbiased estimate

5.25 × 3 = 15.75

Therefore, the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square foot is 15.75

Solutions To Estimation And Descriptive Distributions Exercises Chapter 7 Milton Page 221 Exercise 4 Problem 6

Given problem statement,X is the number of requests for the system received per hour.

A random sample from Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Poisson distribution: P(X = x) = \(\frac{e^{-\lambda}(\lambda)^x}{x !}\)

Given : The random variable X is the number of requests for the system received per hour.

Also X is the Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Find the unbiased estimate for λs

Hence, the sample mean is the unbiased estimator of the population mean.

Then the estimator is \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\), \(\widehat{\lambda s}=\bar{X}\)

Given problem statement,X is the number of requests for the system received per hour.

A random sample from Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of request received per hour.

Given : The random variable X is the number of requests for the system received per hour.

Also X is the Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Find the unbiased estimate for λs

Hence, the sample mean is the unbiased estimator of the population mean. Then the estimator is

\(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\) , \(\widehat{\lambda s}=\bar{X}\)

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of requests received per hour is

ΣiXi = 25 + 30 + 10 + 20 + 24 + 23 + 20 + 15 + 4 = 171

λ8 = \(\frac{171}{9}\)

λ8 = 19

Therefore, the unbiased estimate for the average number of flaws per square yard is 19.

Chapter 7 Estimation And Distributions Examples And Answers Susan Milton Page 221 Exercise 4 Problem 8

Given problem statement,X is the number of requests for the system received per hour.

A random sample from Poisson distribution with parameter λs.

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of request received per quarter hour.

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of requests received per hour is

ΣiXi = 25 + 30 + 10 + 20 + 24 + 23 + 20 + 15 + 4 = 171

λ8 = \(\frac{171}{9}\)

λ8 = 19

Determine the unbiased estimate for the average number of requests received per quarter hour is

1hour = 60minutes

45 Minutes = \(\frac{45}{60}\) hour

Hence, unbiased estimate is

19 × \(\frac{45}{60}\)

= 14.25

Therefore, the unbiased estimate for the average number of requests received per quarter hour is,14.25

Given problem statement,X is the distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location.

A random sample from binomial distribution with interval (0,b).

Determine the unbiased estimator for the average distance.

Given: The random samples X defines the distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location.

Also X follows the binomial distribution with interval(0,b).

Hence, the sample mean value is the unbiased estimator for the population mean.

Find the unbiased estimator for the average distance \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\)

Therefore, the unbiased estimator for the average distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location is \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\)

Probability And Statistics J. Susan Milton Chapter 7 Solved Step-By-Step Page 222 Exercise 5 Problem 10

Given problem statement is the distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location.

A random sample from binomial distribution with interval (0,b).

Next determine the estimate for p at approximately.

Given: The random samples X defines the distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location..

Also X follows the binomial distribution with interval (0,b).

Hence, the sample mean value is the unbiased estimator for the population mean.

Find the unbiased estimator for the average distance \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\)

Determine the variance for X is s2

s2 \(=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

s2 = \(\frac{1}{10 – 1}\) ((10−9.7)2+(8−9.7)2+(7−9.7)2 + (9−9.7)2 + (11−9.7)2 + (10−9.7)2 + (12−9.7)2 +(9−9.7)2 + (8−9.7)2 +(13−9.7)2)

s2 =\(\frac{0.09+2.89+7.29+0.49+1.69+0.09+5.29+0.49+2.89+10.89}{9}\)

s2 = \(\frac{32.1}{9}\)

s2 = 3.567

Therefore, an estimate for p based on the given data it is approximately 3.567.

Given problem statement,X is the distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location.

A random sample from binomial distribution with interval (0,b).

Next determine the estimate for b.

Given: The random samples X defines the distance in inches from the anchored end of rod to the crack location..

Also X follows the binomial distribution with interval(0,b).

Hence, the sample mean value is the unbiased estimator for the population mean.

Find the unbiased estimator for the average distance \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{X}\)

Equating \(\bar{X}\) and E(x)

\(\frac{b}{2}\) = 9.7

b = 9.7 × 2

b = 19.4

Therefore, an estimate for b based on the given data is 19.4.

Online Help For J. Susan Milton Estimation Chapter 7 Exercises Page 222 Exercise 6 Problem 12

Given problem statement, showS is not unbiased estimator for σ.

Assume that E(S)=σ and using the contradiction method to show that S is not unbiased estimator for σ.

Given: Hence, the sample variance value is the unbiased estimator for the population variance.

Show that S is not unbiased estimator

E(S)= σ2

Assume,E(S) = σ

Based on theorem 3.3.2

V(X) = E(X2) −(E(X))2

Hence

V(S)=E(S2) − (E(S))2

V(S) = σ2 − σ2

V(S) = 0

Therefore,S is not unbiased estimator for σ because the variance value is zero.

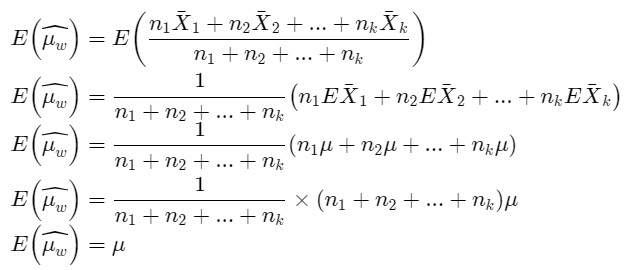

Given problem statement, k independent random samples and it generates unbiased estimators for the mean value.

Just show that the arithmetic average is an unbiased for μ.

So proof \(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\mu\)

Given: show that arithmetic average of the estimator is unbiased for μ.

Prove that \(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\mu\)

Mean value of the estimator is, E[Xi] = μ

\(E\left(\frac{X_1+X_2+\ldots+X_k}{k}\right)=E\left[\frac{1}{k}\left(\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k\right)\right]\)\(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\frac{1}{k} E\left[\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k\right]\)

\(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\frac{E\left[\bar{X}_1\right]+E\left[\bar{X}_2\right]+\ldots+E\left[\bar{X}_k\right]}{k}\)

\(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\frac{\mu+\mu+\ldots \mu}{k}\)

\(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\frac{k \mu}{k}\)

\(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\mu\)

Therefore, the arithmetic average of the estimator \(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\mu\) is an unbiased forμ and its proved.

Step-By-Step Guide To Estimation Exercises Chapter 7 Milton Page 222 Exercise 7 Problem 14

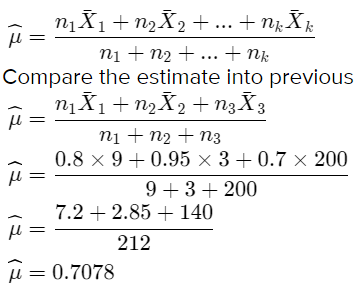

iGiven problem:

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.8, n1 = 9

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.95, n2 = 3

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.7, n3 = 200

Using previous value, for determine the averaging of three values to get the unbiased estimator for μ.

On previous lesson, the arithmetic average of the estimator is unbiased for μ.

\(E\left(\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{k}\right)=\mu\)

Given:

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.8, n1 = 9

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.95, n2 = 3

\(\bar{X}\) = 0.7, n3 = 200

Determine average of three values

\(\widehat{\mu}=\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\ldots+\bar{X}_k}{-k}\)

⇒ \(\widehat{\mu}=\frac{\bar{X}_1+\bar{X}_2+\bar{X}_3}{3}\)

⇒ \(\widehat{\mu}=\frac{0.8+0.95+0.7}{3}\)

⇒ \(\widehat{\mu}=\frac{2.45}{3}\)

⇒ \(\widehat{\mu}\) = 0.8167

Therefore, Averaging the three values to get the estimate for μ is 0.8167.

Given problem: \(=\frac{n_1 X_1+n_2 X_2+\ldots+n_k X_k}{n_1+n_2+\ldots+n_k}\)

Just show that given is an un biased for μ .so proof, E(\(\widehat{\mu_w}\)) = μ

Given: \(=\frac{n_1 X_1+n_2 X_2+\ldots+n_k X_k}{n_1+n_2+\ldots+n_k}\)

Then prove , E(\(\widehat{\mu_w}\)) = μ

Therefore, given \(\widehat{\mu_w}\) Is ann unbiased estimator for μ and its proved

Exercise Solutions For Chapter 7 Susan Milton Estimation And Distributions Page 222 Exercise 7 Problem 16

Previous problem: \(\widehat{\mu_w}\) = \(=\frac{n_1 X_1+n_2 X_2+\ldots+n_k X_k}{n_1+n_2+\ldots+n_k}\)

Using previous problem data and next deterine the estimate for based on the previous problem.

Given: \(=\frac{n_1 X_1+n_2 X_2+\ldots+n_k X_k}{n_1+n_2+\ldots+n_k}\)

Therefore compared to the previous problem then the weighted average mean is less than mean.

Given problem statement,X defines the number of heads obtained when a coin is tossed four times.

Determine the expected value E[X] and variance Var[X] for the variable X.

Given: The random variable X defines the number of heads obtained when a coin is tossed four times.

Also X follows the binomial distribution with parameters

n = 4

p = \(\frac{1}{2}\)

Determine the expected value

E[X] = np

E[X]= 4 × \(\frac{1}{2}\)

E[X] = 2

Find the variance

Var[X] = np(1 − p)

Var[X] = 4 × \(\frac{1}{2}\) (1−\(\frac{1}{2}\))

Var[X]= 4 ×\(\frac{1}{2}\) × \(\frac{1}{2}\)

Var[X] = 1

Therefore, the expected value and variance for the variable X is Expected Value: E[X] = 2, Variance: Var[X] = 1

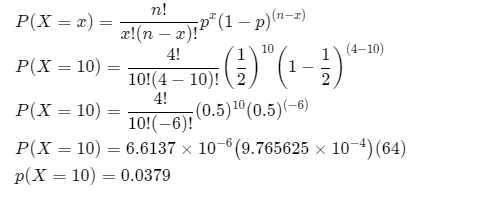

Page 223 Exercise 8 Problem 18

Given problem statement,X defines the number of heads obtained when a coin is tossed.

The number of heads obtained at 10 times. That means X = 10 and binomial distribution with parameters

n = 4

p = \(\frac{1}{2}\)

Given: The random variableX defines the number of heads obtained when a coin is tossed four times.

Also X follows the binomial distribution with parameters,

n = 4

p = \(\frac{1}{2}\)

When heads obtained at ten times.

That means X = 10 and apply all values in the binomial distribution formula

Therefore, the probability for obtain the number of heads at 10 times, 0.0379.

Given problem statement,X defines the number of heads obtained when a coin is tossed.

Determine the expected value E[X] and variance Var[X]

for based on 10 observations of the variable X.

Given: The random variable defines the number of heads obtained when a coin tossed.

That means [X = 10] and binomial distribution with parameters

n = 4

p = \(\frac{1}{2}\)

The mean and variance was given

E[X] = 2

Var[X] = 1

Then determine the mean and variance for ten observations.

Mean is summation of all observations divided by number of observations.

The means value is 2.

Variance is sum of squares of each observation subtracted by the mean.

Hence, the variance value is 1

Therefore, based on 10 observations the expected value and variance for the variable X is Expected Value: E[X] = 2 Variance: Var[X] = 1

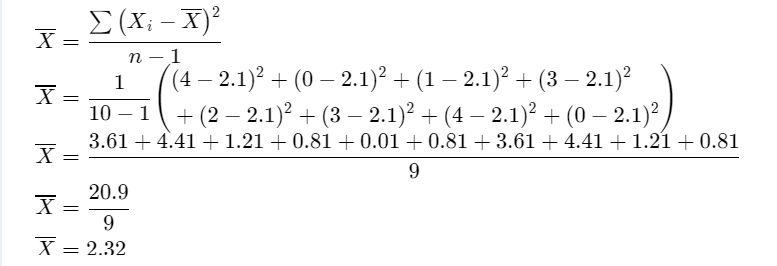

Page 223 Exercise 8 Problem 20

Given problem statement, X defines the number of heads obtained when a coin is tossed.

The variance Var[X] of the variable X is an unbiased estimate for s2.

Next determine the variance of the value \(\bar{X}\)

\(\bar{X}=\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n-1}\)

Given: The random variable defines the number of heads obtained when a coin tossed.

Apply n = 10 for the observations

The unbiased estimate for the variance of X is s2.

Then the \(\bar{X}\)

Given: The Random Samples are X1,X2,X3 ,…..,Xn with mean and variance.

Using mean μ and the variance σ2

Value for prove that the below function

\(\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n}=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{n}\)

Given: The Random Samples are X1,X2,X3 ,…..,Xn with mean μ and variance σ2.

Prove that \(\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n}=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{n}\) and E(s2 ) = σ2

Consider LHS

Therefore, the Random Samples X1,X2,X3 ,…..,Xn with mean μ Value and variance σ2 Value for \(\frac{\sum\left(X_i-\bar{X}\right)^2}{n}=\frac{(n-1) s^2}{n}\) and its proved

Page 223 Exercise 10 Problem 22

Given: The Random Sample X1,X2,X3 ,…..,Xm with size m and parameter n.

Using method of moments technique to Determine the first moment of the given sample.

Given: The Random Sample X1,X2,X3 ,…..,Xm with size m and parameter n.

Also, it follows the Binomial Distribution X1,X2,X3 ,…..,Xm

Use method of moments to find the estimator for p,

M1 = \(\frac{\sum_i X_i}{m}=\bar{X}\)

Find the first moment of the sample, E(X) = np

\(n \hat{p}=\bar{X}\) \(\hat{p}=\frac{\bar{X}}{n}\)

Therefore, using Method of Moments technique for find the estimator of p is \(\hat{p}=\frac{\bar{X}}{n}\) and its proved.

Introduction To Probability And Statistics Chapter 6 Exercises Solutions Page 192 Exercise 1 Problem 1

In this case a statistical study is appropriate.

The population of interest is consisted of the wind speed per day.

An engineer can measure the speed over some period of time and then determine various statistics of that sample including

1. Mean

2. Minimal

3. Maximal value

4. Sample deviance etc..

The draw necessary conclusions about the population based on observing the given sample.

Thus, In this case, a statistical study is appropriate because of various statistics of that sample including Mean, Minimal, maximal value, sample deviance, etc. Hence, the maximum wind speed per day at all sites can be designed.

Read and Learn More J Susan Milton Introduction To Probability And Statistics Solutions

In this case study:

A statistical study is appropriate. Because the population of interest is consisted of two groups of cuttings:

1. A control group

2. A test group

Various static test can be used for this kind of problem to determine whether or not there is a statistical significant between group or in this case whether or not indoleacetic acid really is effective.

Thus, the botanist thinks that indoleacetic acid is effective in stimulating the formation of roots in cutting from the lemon tree.

Solutions To Descriptive Distributions Exercises Chapter 6 Susan Milton Page 192 Exercise 3 Problem 3

In this case study:

A statistical study is not appropriate.

Because the sample might be too small to correctly approximate the average time and cost required to complete the job.

Thus, an architectural firm is to sublet a contract for a wiring project.

Chapter 6 Descriptive Distributions Examples And Answers Susan Milton Page 192 Exercise 4 Problem 4

In this case study:

A statistical study is not appropriate. Because the length of the sessions does not tell us anything about the occupancy of the terminal.

Thus, A statistical study is not appropriate in a computer system that has a number of remote terminals attached to it. Because the length of the sessions does not tell us anything about the occupancy of the terminal.

In this case study:

A statistical study is appropriate.

Because the population of interest is consisted of the affected workers. We can also draw a random sample out of those 50000 workers, because the original population might be too large to study in its entirety.

Sampling the people from population would help us draw necessary conclusion about the population.

Thus, the statistical study is appropriate. Because the population of interest consists of the affected workers. prior to changing from the traditional is appropriate and also drew a random sample out of those 50,000 workers, because the original population might be too large to study entirety.

Probability And Statistics J. Susan Milton Chapter 6 solved Step-By-Step Page 192 Exercise 6 Problem 6

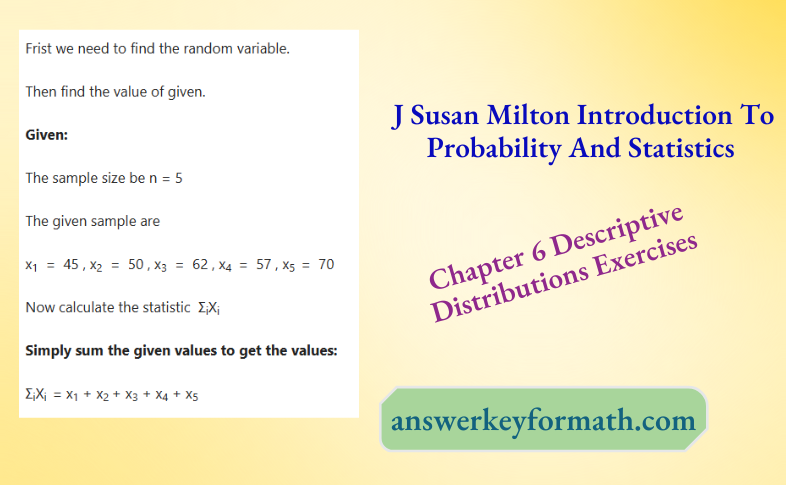

Frist we need to find the random variable.

Then identify with know or unknown mean.

Given:

Random variable = X1

Particular level = 24 hours period.

Now , Let X1 be the random variable for the particular level for the first 24-hour period.

The random variable is normally distributed with unknown mean μ and also unknown variance is σ, so that we get X1 ≈ N(μ,σ2)

Thus, the distribution of this random variable is X1 ≈ N(μ,σ2).

Now apply the value in the equation:

ΣiXi = 45 + 50 + 62 + 57 + 70

ΣiXi = 284

The sample size be n = 5

The given sample are

x1 = 45 , x2 = 50 , x3 = 62 , x4 = 57 , x5 = 70

Now calculate the statistic ΣiXi/n

Simply sum the given values to get the values:

ΣiX2i = x21 + x22 + x23 + x24 + x25

Now apply the value in the equation

ΣiX2i = 452 + 502 + 622 + 572 + 702

ΣiX2i = 16518

The sample size be n = 5

The given sample are

x1 = 45 , x2 = 50 , x3 = 62 , x4 = 57 , x5 = 70

Now calculate the statistic ΣiX2i

Simply sum the given values to get the values:

\(\Sigma_i \frac{X_i}{n}=\frac{x_1+x_2+x_3+x_4+x_5}{n}\)

Now apply the value in the equation

\(\Sigma_i \frac{X_i}{n}=\frac{45+50+62+57+70}{5}\)

⇒ \(\Sigma_i \frac{X_i}{n}\) = 56. 8

Now we going to calculate the statistic maxi {Xi},so that we to find the biggest value from the given sample.

By looking the values, we can easily identify them maxi {Xi}= x5 = 70.

Now we going to calculate the statistic mini {Xi}, so that we to find the biggest value from the given sample.

By looking the values, we can easily identify them mini {Xi} = x1 = 45.

Thus, the random variable value is ΣiXi = 284

ΣiXi = 16518

\(\Sigma_i \frac{X_i}{n}\) = 56.8

Maxi {Xi}= x5 = 70.

Mini {Xi} = x1 = 45.

Frist we need to find the random variable.

Then find the value of given.

The sample size be n = 5

The given sample are

x1 = 45 , x2 = 50 , x3 = 62 , x4 = 57 , x5 = 70

The random variables X5and \(\frac{X_5-\mu}{\sigma}\) are not a statistic.

Since this random variable we can’t determine its numerical value from a random sample.

Thus, this random variable we can’t determine its numerical value from a random sample.

Page 193 Exercise 7 Problem 9

Given:

The number is = 02,03,04,05,06,07

First, we need to find the length of the categories.

To construct a Stem and leaf diagram, we have to use the initial two digits as stems, in this case 02,03,04,05,06,07

The third digit will be representation a leaf.

By applying the logic to the given sample, so we get that easily construct the given stem and leaf diagram:

02 ∣ 0

03 ∣ 079909

04 ∣ 407549262

05 ∣ 75012268431

06 ∣ 1612120

07 ∣ 0

Thus, the construct Stem and leaf diagram. By applying the logic to the given sample, so we get that easily construct the given stem and leaf diagram:

02 ∣ 0

03 ∣ 079909

04 ∣ 407549262

05 ∣ 75012268431

06 ∣ 1612120

07 ∣ 0

Online Help For J. Susan Milton Descriptive Distributions Chapter 6 Exercises Page 193 Exercise 7 Problem 10

By turning the stem and leaf diagram to the side , we can very clearly see that the diagram has a notorious bell shape, thus confirming the persons suspicious of it being normally distributed.

Hence we should not be surprised if we hear someone claim such thing.

First we need to find the biggest value.

Then we are going to find the smallest value.

Given:

First half unit = \(\frac{1}{1000}\)

Other Half unit= .0005

To break the given data into six category , first we have to find the length of the interval convering the data.

The biggest value from the sample which is 0.070

The smallest value from the sample which is 0.020

0.070 − 0.050 = 0.020

To find the length of the categories for that we going to divide the length of the whole interval by the number of categories.

Now, Split data into 6 categories and we calculate the length of 0.02 units.

To divide those number and round it up to the nearest number that has the same number of decimals as the original data.

\(\frac{0.02}{6}\) = 0.00333333

The data has three decimals, so we going to round the calculated number to 0.010.

Hence the length of each category.

The lower boundary for the first category is obtained by subtracting 0.0005 from the lowest value of the sample which is 0.02.

0.02 − 0.0005 = 0.0195

Hence the lower boundary for the first category is 0.0195.

To find the remaining categories, we have to successively add the length of each category starting from the lowest boundary, which is 16.25.

0.0195 + 0.010 = 0.0295 ⇒ [0.0195,0.0295⟩

0.0295 + 0.010 = 0.0395 ⇒ [0.0295,0.0395⟩

0.0395 + 0.010 = 0.0495 ⇒ [0.0395,0.0495⟩

0.0495 + 0.010 = 0.0595 ⇒ [0.0495,0.0595⟩

0.0595 + 0.010 = 0.0695 ⇒ [0.0595,0.0695⟩

0.0695 + 0.010 = 0.0795 ⇒ [0.0695,0.0795⟩

Thus, the method outlined in this section breaks these data into six categories and also add the length of each category starting from the lowest boundary, which is 16.25

0.0195 + 0.010 = 0.0295 ⇒ [0.0195,0.0295⟩

0.0295 + 0.010 = 0.0395 ⇒ [0.0295,0.0395⟩

0.0395 + 0.010 = 0.0495 ⇒ [0.0395,0.0495⟩

0.0495 + 0.010 = 0.0595 ⇒ [0.0495,0.0595⟩

0.0595 + 0.010 = 0.0695 ⇒ [0.0595,0.0695⟩

0.0695 + 0.010 = 0.0795 ⇒ [0.0695,0.0795⟩

Step-By-Step Guide To Descriptive Distributions Exercises Chapter 6 Milton Page 193 Exercise 8 Problem 12

Since the stem and leaf diagram is slightly skewed to the left instead of having a normal bell shape it can be suggested that the data comes from a family of X2 distribution.

Thus, the stem and leaf diagram is slightly skewed to the left instead of having a normal bell shape.

Given:

The number is = 5,6,7,8,9,10

First, we need to find the length of the categories and then find the value.

Now

To construct Stem and leaf diagram, we have to use initial digits as “stems”, in this case 5,6,7,8,9,10

The second digits will be representation a leaf.

By applying the logic to the given sample, so we get that easily construct the given stem and leaf diagram:

5 ∣ 3

6 ∣ 12728257

7 ∣ 6467816399117494

8 ∣ 8728710275241

9 ∣ 056127563

10 ∣ 0

Thus, the construct for the Stem and leaf diagram is given below:

5 ∣ 3

6 ∣ 12728257

7 ∣ 6467816399117494

8 ∣ 8728710275241

9 ∣ 056127563

10 ∣ 0

To construct Stem and leaf diagram, we have to use initial digits as “stems”, in this case, 5,6,7,8,9,10

The second digit will be a representation a leaf.

By applying the logic to the given sample, so we get easily construct the given stem and leaf diagram:

5 ∣ 3

6 ∣ 12728257

7 ∣ 6467816399117494

8 ∣ 8728710275241

9 ∣ 056127563

10 ∣ 0

By turning this stem and leaf diagram to the side, we can very clearly see that the diagram has a notorious bell shape, thus confirming the assumption of it being normally distributed.

Thus, the assumption X is normally distributed. The given stem and leaf diagram is

5 ∣ 3

6 ∣ 12728257

7 ∣ 6467816399117494

8 ∣ 8728710275241

9 ∣ 056127563

10 ∣ 0

Exercise Solutions For Chapter 6 Susan Milton Descriptive Distributions Page 194 Exercise 10 Problem 15

Given:

The number is = 0,1,2,3,4,5

First, we need to find the length of the categories and then find the value.

Now

To construct Stem and leaf diagram, we have to use initial digits as “stems”, in this case 0,1,2,3,4,5

The second digits will be representation a leaf.

By applying the logic to the given sample, so we get that easily construct the given stem and leaf diagram:

0 ∣ 578

1 ∣ 19358620972988457

2 ∣ 06443483575730231

3 ∣ 6281007541

4 ∣ 05

5 ∣ 0

Thus, the construct for Stem and leaf diagram is given below:

0 ∣ 578

1 ∣ 19358620972988457

2 ∣ 06443483575730231

3 ∣ 6281007541

4 ∣ 05

5 ∣ 0

Given:

The assumption that X is not normally distributed.

There might be a slight reason that X is not normally distributed as by turning the stem and leaf diagram to the sight.

We can see that it does not exactly resemble perfect symmetrical bell shape like a normal distribution, but rather slightly skewed to the left.

Thus, we can be suspicious about the data not being normally distributed.

Thus, the assumption that X mis not normally distributed.

0 ∣ 578

1 ∣ 19358620972988457

2 ∣ 06443483575730231

3 ∣ 6281007541

4 ∣ 05

5 ∣ 0

Page 194 Exercise 10 Problem 17

First we need to find the biggest value.

Then we going to find the smallest value.

To break the given data into seven category , first we have to find the length of the interval covering the data.

The biggest value from the sample which is 5.0

The smallest value from the sample which is0.5

5.0 − 0.5 = 4.5

Whole interval by the number of categories.

Now

Split data into 7 categories and we calculate the length of 4.5 units.

To divide those number and round it up to the nearest number that has the same number of decimals as the original data.

\(\frac{4.5}{7}\) = 0.642857

The data has one decimals, so we going to round the calculated number to0.6.

Hence the length of each category.

The lower boundary for the first category is obtained by subtracting0.7

0.5−0.05 = 0.45

Hence the lower boundary for the first category is0.45.

To finding the remaining categories, we have to successively add the length of each category starting from the lowest boundary, which is n 0.45.

0.45 + 0.7 = 1.15 ⇒ [0.45,1.15⟩

1.15 + 0.7 = 1.85 ⇒ [1.15,1.85⟩

1.85+0.7 = 2.55 ⇒ [1.85,2.55⟩

2.55 + 0.7 = 3.25 ⇒ [2.55,3.25⟩

3.25 + 0.7 = 3.95 ⇒ [3.25,3.95⟩

3.95 + 0.7 = 4.65 ⇒ [3.95,4.65⟩

4.65 + 0.7 = 5.35 ⇒ [4.65,5.35⟩

Given:

Let one variable be X

A random sample of 50 mosses yields under observation

First, we need to find the frequency table.

Then we going to find the histogram of data.

The frequency table constructed by observing and counting how many of the values from the sample are located inside of each of those six categories.

The table is:

The relative frequency histogram data

Thus, the looking the shape of the histogram, we can clearly see that it resembles the bell shapes, but is slightly skewed to the left, it is just like the stem and leaf.

Diagram we calculated easier. Hence having characteristics is not normal density.

The table is given below:

Given:

The 25th, 50th,75th, and 100th percentiles for X

First, we need to find the point X value.

Then we going to find the binomial value.

The first quartile of a random variable X is a point p 0.25

Such that P(X < p 0.25) ≤ 0.25

P(X ≤ p0.25) ≥ 0.25

Then we can write as: P(X < p0.25) ≤ 0.25 and the first quartile of a random variable is P(X ≤ p0.25) ≥ 0.25

Thus, the first quartile of a random variable X is P(X ≤ p0.25) ≥ 0.25.

Page 195 Exercise 11 Problem 20

Given:

n = 20

p = 0.5

First we need to find the point X value .

Then we going to find the binomial value.

If X is binomial variable with n = 20 and p = 0.5, then its first quartile is obtained by using the definition, and table from appendix or a mathematical software such as R.

The first percentile of this distribution is p0.25 = 8

P(X < 8) = P(X ≤ 7) = 0.132 ≤ 0.25

P(X ≤ 8) = 0.2517 ≥ 0.25

Thus, the first quartile of a random variable p0.25 = 8.

Given: \(\int_0^p e^{-x} d x\) = 0.25

First we need to find the point X value.

Then we going to find the binomial value

To calculate exponential random variables with β = 1,

We have to solve the given equation:

\(\int_0^p e^{-x} d x\) = 0.25

Let integrate the given equation:

\(\int_0^p e^{-x} d x\)= \(\left.\left(-e^{-x}\right)\right|_0 ^p\)

\(\int_0^p e^{-x} d x\)= \(-\left(e^{-p}-e^0\right)\)

Where e0= 1

\(\int_0^p e^{-x} d x\) = \(-\left(e^{-p}-1\right)\)

\(\int_0^p e^{-x} d x\)= \(1-e^{-p}\) ……………………….. (1)

To solve equation(1) so that we get

1 − e − p = 0.25

⇔ 0.75 = e − p

⇔ ln 0.75 = −p

⇔p = −ln 0.75 ≈ 0.2877

Thus, the pointp value is ⇔ p0.25 = −ln0.75.

Page 195 Exercise 12 Problem 22

Given:

(Deciles.) The 10th,20th,30th,40th,50th,60th,70th,80th,90th,and100th

First, we need to find the point 40th deciles X value.

Then we going to find the binomial value.

The 4th decile of a random variable X is a point p0.4

Such that P(X < p0.4) ≤ 0.4

P (X ≤ p0.4 ) ≥ 0.4

Then can write the fourth decile of the random variable as P(X ≤ p0.4) ≥ 0.4

Thus, the 4th decile of random variable of a random variable X is P(X ≤ p0.4) ≥ 0.4.

Given: λ = 20

First we need to find the point X value

Then we going to find the Poisson value.

If X is Poisson random variable with λ = 20, then its first 6th decile is obtained by using the definition, and table from appendix or a mathematical software such as R.

The first percentile of this distribution is p 0.6= 11

P(X<11) = P(X ≤ 10) = 0.5830 ≤ 0.6

P(X ≤ 11) = 0.6968 ≥ 0.6

Thus, the 6th decile X value is p0.6 = 11.

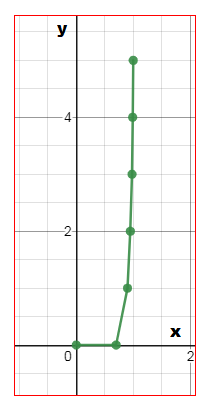

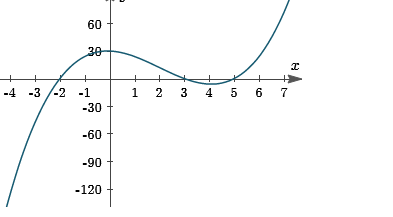

First we need to find the point X value .

Then diagram the relative cumulative frequency.

The relative cumulative frequency ogive from the data :

By using projection method , approximate the first quartile for X by drawing the horizontal line at he height of 25 then add a perpendicular line.

That passes through the previously obtained point on the relative cumulative frequency ogive to read the approximate value for it.

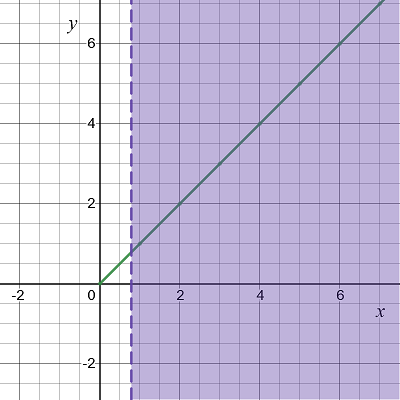

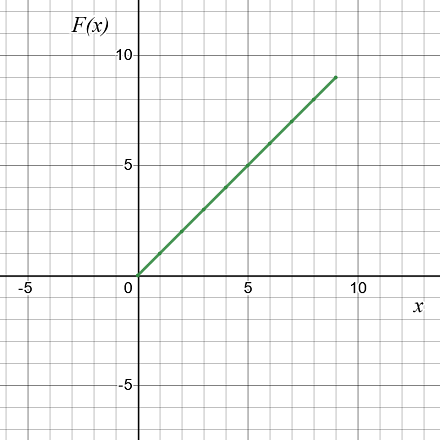

The related graph is:

Thus, the approximate first quartile X value is p0.25 = 0.0 415.

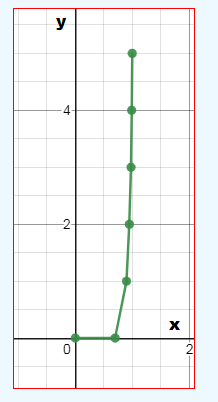

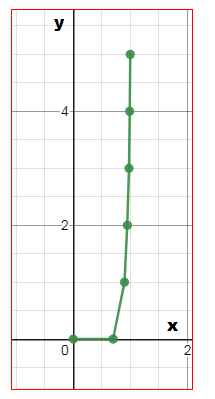

First we need to find the point X value .

Then diagram the relative cumulative frequency.

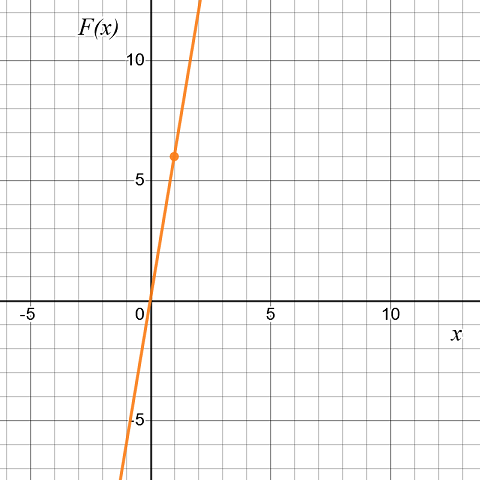

The relative cumulative frequency ogive from the data :

By using projection method , approximate the first quartile for X by drawing the horizontal line at he height of 40 (it means 40%)then add a perpendicular line.

That passes through the previously obtained point on the relative cumulative frequency ogive to read the approximate value for it.

The related graph is:

Thus, the approximate fourth decile X value is p0.4 = 7.7.

Introduction To Probability And Statistics Chapter 4 Exercises Solutions Page 127 Exercise 1 Problem 1

Given:

The function f(x) = kx where 2 ≤ x ≤ 4

To find – The value of k

Method: The method here used is probability and continuous random variable.

The function f(x) = kx.

For, 2 ≤ x ≤ 4 variable.

Assume x = 3.

f(3) = 3k

Consider f(3) = 1 for the function f(x).

1 = 3k

k = \(\frac{1}{3}\)

Hence, it is verified that the value of k is k = \(\frac{1}{3}\)

Read and Learn More J Susan Milton Introduction To Probability And Statistics Solutions

Given:

The function f(x) = kx

Where 2 ≤ x ≤ 4.

To find:

Find the value of probabilities of P(2.5 ≤ X ≤ 3).

Method: The method here used is probability and continuous random variable.

The function f(x) = kx where 2 ≤ x ≤ 4

Substitute x = 3

f(3) = 3k

The function of P[2.5≤X≤3]

Here, there is no function that occurs between the X = 2.5 and X = 3 X.

Hence, it is verified that the function f(x) is not possible for the values P(2.5 ≤ X ≤ 3).

J. Susan Milton Chapter 4 Continuous Distributions Answers Page 127 Exercise 1 Problem 4

Given:

The function f(x) = kx

where 2 ≤ x ≤ 4.

To find – Find the probability of P(2.5 < X ≤ 3)

Method: The method here used is probability and continuous random variable.

The function f(x) = kx

For P (2.5 < X ≤ 3)

The equation is, f(x) = 3k

Assume k = 2

The function

f(x) = 3 × 2

f(x) = 6

Hence, it is verified that the function f(x) at P(2.5 < X ≤ 3) is f(x) = 6

Given:

The function f(x) = \(\left(\frac{1}{10}\right) e^{\frac{-x}{10}}\)

To find – The function is a continuous random variable

Method : The method used is a probalility and continuous random variable

The given function f(x) =\(\left(\frac{1}{10}\right) e^{\frac{-x}{q p}}\)

Substitute 1 or x

f(1) \( = \frac{1}{10} e^{\frac{-x}{10}}\)

f(1) = 0.0904

Hence, it is verified that the density of the function is f(1) = 0.0904

Solutions To Continuous Distributions Exercises Chapter 4 Susan Milton Page 128 Exercise 2 Problem 6

Given:

The function f(x)= \(\frac{1}{10} e^{\frac{-x}{10}}\)

To find – Find the density at 7 minutes

Method: The method used here are probability and continuous random variable.

The given function

f(x) = \(\frac{1}{10} e^{\frac{-x}{10}}\)

For the density of 7 minutes

f(7) = \(\frac{1}{10} e^{\frac{-7}{10}}\)

f(7) = 0.0496

Hence, it is verified that the density of the function at 7 minutes is f(7) = 0.0496

Given:

The function f(x) = \(\frac{1}{10} e^{\frac{-x}{10}}\)

To find – The probability of density of call last between 1 to 2 minutes.

Method: The method used here is probability and continuous random variable.

The given function is.

f(x) = \(\)

For the call last one minute

f(1) = \(e^{\frac{-1}{10}}\)

f(1) = 0.0904

For the call lasts two minutes

f(2) = 0.1 × \(e^{\frac{-2}{10}}\)

f(2) = 0.0607

The probaability of the call lasts one minuteto two minutes, the density of the function gradually increases to show the calls gain more and more density by increasing the call time.

Hence, it is verified that the call lasts from one to two minutes then the density of the call is also increasing.

Given:

The graph of bird moving in θ.

To find – The angle of the bird moving

Method: The method used in this problem is probability, continuous random variable, and graphical method.

Let the function f for the interval [0,2Π].

f(θ)\(=\int_0^{2 \Pi} \theta\)

Reduce the equation.

f(θ) = 2Π − 0

f(θ) = 2Π

Hence, it is verified that the density of the function f with the interval [0,2Π] is f(θ) = 2Π

Chapter 4 Continuous Distributions Examples And Answers Susan Milton Page 128 Exercise 3 Problem 9

Given:

The graph of moving bird denoted in θ.

To find – Sketch the graph of the moving bird in uniform motion with interval [0,2Π].

Method: The method used in this problem is probability, continuous random variable, and graphical method.

The function of the moving bird in uniform distribution interval [0,2Π].

Let \(=\int_0^{2 \Pi} \theta\)

Reduce the equation.

f(θ) = Π + Π

f(θ) = 2Π

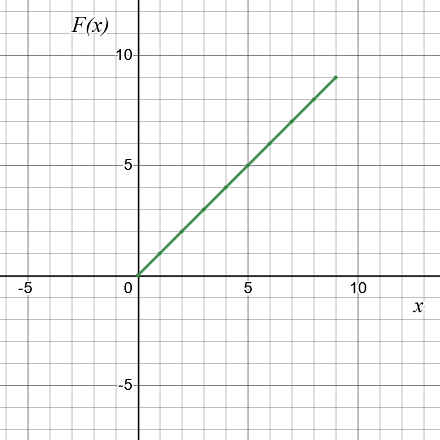

The graph of the moving bird.

Hence, it is verified that the graph of a uniform distribution over the interval.

Given:

The function f of moving bird in the angle θ.

To find – Sketch the graph of the function fin the interval [0,2Π].

Method: The method used in this problem is a probability, continuous random variable, and graphical method

Graph the function f and shade the orient within \(\frac{\Pi}{4}\)radians of home.

The graphs shows, the bird flying in the direction of \(\frac{\Pi}{4}\) radians from home in the straight direction from home.

Hence, it is verified that the

Given:

The function f mof the interval [0,2Π].

To find – Find the probability of the function f with the orient within the

\(\frac{\Pi}{4}\) radians of home.

Method: The method used in this problem is a probability, continuous random variable, and graphical method.

The function for orient within the \(\frac{\Pi}{4}\) radians of the home .

f(θ)\( =\int_0^{2 \Pi} \theta+\frac{\Pi}{4}\)

Reduce the equation.

f(θ) = \(2 \Pi+\frac{\Pi}{4}\)

f(θ) = \(\frac{9 \Pi}{4}\)

Hence, it is verified that the possibilities of the moving bird within the

\(\frac{\Pi}{4}\) radians of home is \(=\frac{9 \Pi}{4}\)