Legendre Polynomials Exercise 4

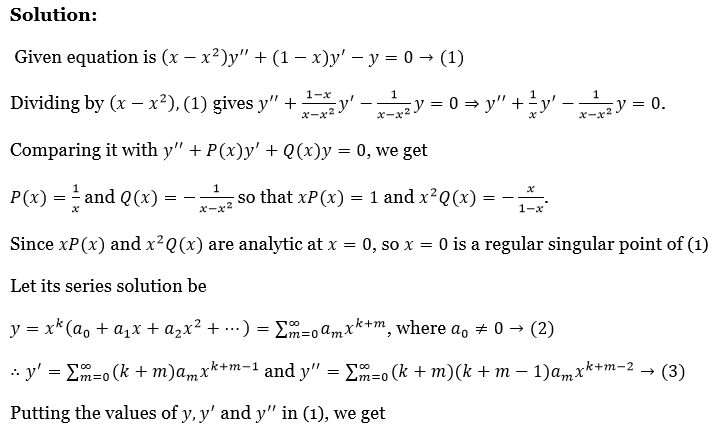

1. Define Legendre’s differential equation.

Solution:

The differential equation of the form \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}-2 x \frac{d y}{d x}+n(n+1) y=0\) is called Legendre’s differential equation (or Legendre’s equation), where n is a constant.

2. Show that 1) \(y=a_0\left[x^n-\frac{n(n+1)}{2(2 n-1)} x^{n-2}+\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} x^{n-4}+\cdots\right]\)

2) \(y=a_0\left[x^{-n-1}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2(2 n+3)} x^{-n-2}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)(n+3)(n+4)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n+3)(2 n+5)} x^{-n-5}+\ldots\right]\)are solutions of

Legendre’s equation \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}-2 x \frac{d y}{d x}+n(n+1) y=0\)

Solution:

The Legendre’s equation is \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}-2 x \frac{d y}{d x}+n(n+1) y=0 \rightarrow(1)\) it is can be solved in series of descending power of x.

Let us assume, y = \(y=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r x^{k-r}\) be solution of (1)

Now \(\frac{d y}{d x}=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r(k-r) x^{k-r+1} \text { and } \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r(k-r)(k-r-1) x^{k-r-2}\)

Substituting these in (1), we have

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) \sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r(k-r)(k-r-1) x^{k-r-2}-2 x \sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r(k-r) k^{k-r-1}+n(n+1) \sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r x^{k-r}=0\)

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r\left[(k-r)(k-r-1) x^{k-r-2}+\{n(n+1)-(k-r)(k-r-1)-2(k-r)\} x^{k-r}\right]=0\)

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r\left[(k-r)(k-r-i) x^{k-r-2}+\{n(n+1)-(k-r)(k-r+1)\} x^{k-r}\right\}=0\)

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r\left[(k-r)(k-r-1) x^{k-r-2}+\left\{n^2-(k-r)^2+n-(k-r)\right\} x^{k-r}\right]=0\)

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r\left[(k-r)(k-r-1) x^{k-r-2}+(n-k+r)(n+k-r+1) x^{k-r}\right]=0 \rightarrow(2)\)

Now (2) being an identity, we can equal to zero the coefficient of power of x.

∴ The equation to zero the coefficient of the highest power of x, i.e. of xk, we have

⇒\(a_0(n-k)(n+k+1)=0\)

Now \(a_0 \neq 0\) as it is the coefficient of the first term with which we start to write the series.

∴ \(k=n \text { or } k=-(n+1) \rightarrow(3)\)

Equation to zero the coefficient of the next lower power of x i.e. \(x^{k-1}\), we have

⇒\(a_1(n-k+1)(n+k)=0\)

∴ a1 = 0, since neither (n-k+1) nor (n+k) is zero by virtue of (3)

Again equation to zero is the coefficient of the general term i.e. \(x^{k-r}\), we have

⇒ \(a_{r-2}(k-r+2)(k-r+1)+(n-k+r)(n+k-r+1) a_r=0\)

∴ \(a_r=-\frac{(k-r+2)(k-r+1)}{(n=k+r)(n+k-r+1)} a_{r-2} \rightarrow \text { (4) }\)

Putting r = 3, a3 = \(-\frac{(k-1)(k-2)}{(n-k+3)(n+k-2)} a_1=0\) since a1 = 0

∴ We have a1 = a3 = a5 = .. = 0 (each).

Case 1: supporting K = n

Then from (4), we have ar = \(-\frac{(n-r+2)(n-r+1)}{r(2 n-r+1)} a_{r-2} \rightarrow \text { (5) }\)

Putting r = 2,4….. in (5) we get \(a_2=-\frac{n(n-1)}{2(2 n-1)} a_0\)

\(a_4=-\frac{(n-2)(n-3)}{4(2 n-3)} a_2=\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} a_0 \text { etc }\)∴ \(y=a_0 x^n+a_n x^{n-2}+a_4 x^{n-4}+\cdots\)

⇒ \(y=a_0\left[x^n-\frac{n(n+1)}{2(2 n-1)} x^{n-2}+\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} x^{n-4}+\cdots\right] \rightarrow(6)\)

Which is one solution for Legndre’s equation

Legendre Polynomials Solved Examples Step-By-Step

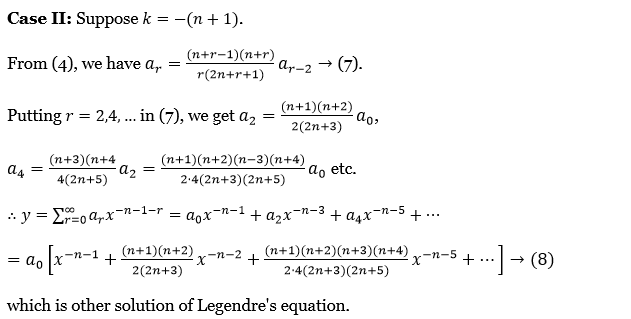

Case 2: Support k = -(n+1)

From (4) we have \(a_r=\frac{(n+r-1)(n+r)}{r(2 n+r+1)} a_{r-2} \rightarrow(7)\)

Putting r = 2,4 …. in (7), we get \(a_2=\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2(2 n+3)} a_0 \text {, }\)

⇒ \(a_4=\frac{(n+3)(n+4}{4(2 n+5)} a_2=\frac{(n+1)(n+2)(n-3)(n+4)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n+3)(2 n+5)} a_0 \text { etc. }\)

∴ \(y=\sum_{r=0}^{\infty} a_r x^{-n-1-r}=a_0 x^{-n-1}+a_2 x^{-n-3}+a_4 x^{-n-5}+\cdots\)

⇒ \(a_0\left[x^{-n-1}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2(2 n+3)} x^{-n-2}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)(n+3)(n+4)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n+3)(2 n+5)} x^{-n-5}+\cdots\right] \rightarrow \text { (8) }\)

Which is another solution of Legendre’s equation.

Solved Exercise Problems On Legendre Polynomials

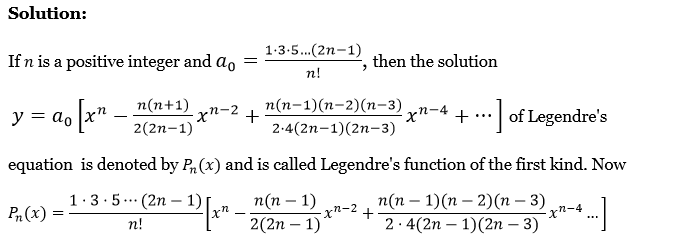

3. Define Legendre’s function of the first kind.

Solution:

If n is a positive integer and \(a_0=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \ldots(2 n-1)}{n!}\), then the solution

⇒ \(y=a_0\left[x^n-\frac{n(n+1)}{2(2 n-1)} x^{n-2}+\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} x^{n-4}+\cdots\right]\) of Legendre’s equation is denoted by pn(x) and is called Legendre’s function of the first kind. Now

⇒ \(P_n(x)=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdots(2 n-1)}{n!}\left[x^n-\frac{n(n-1)}{2(2 n-1)} x^{n-2}+\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} x^{n-4} \cdots\right]\)

Applications Of Legendre Polynomials With Worked Examples

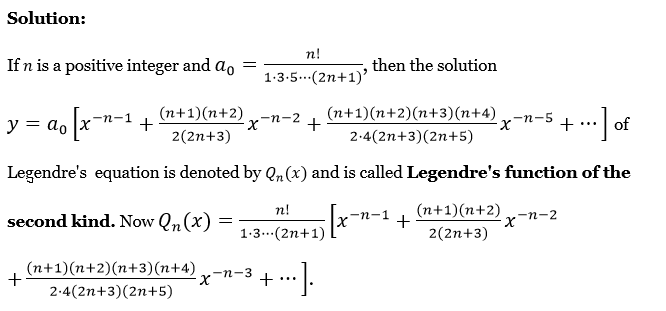

4. Define Legendre’s function of the second kind.

Solution:

Legendre’s function of the second kind

If n is a positive integer and \(a_0=\frac{n!}{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdots(2 n+1)}\), then the solution

⇒ \(y=a_0\left[x^{-n-1}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2(2 n+3)} x^{-n-2}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)(n+3)(n+4)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n+3)(2 n+5)} x^{-n-5}+\cdots\right] \text { of }\)

Legendre’s equation is denoted by Qn(x) and is called Legendre’s function of the second kind.

Now, \(Q_n(x)=\frac{n!}{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n+1)}[x^{-n-1}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)}{2(2 n+3)} x^{-n-2}+\frac{(n+1)(n+2)(n+3)(n+4)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n+3)(2 n+5)} x^{-n-3}+\cdots\)

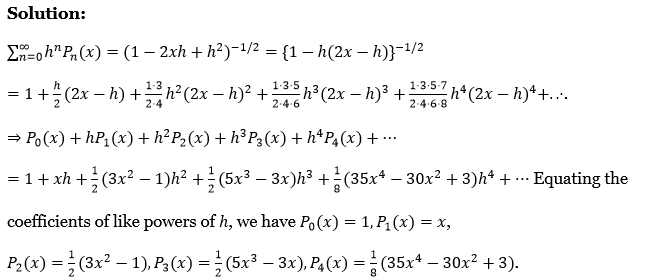

5. Show that \(P_0(x)=1, P_1(x)=x, P_2(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(3 x^2-1\right), P_3(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(5 x^3-3 x\right)\)

\(P_4(x)=\frac{1}{8}\left(35 x^4-30 x^2+3\right)\)

Solution:

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)=\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\{1-h(2 x-h)\}^{-1 / 2}\)

⇒ \(1+\frac{h}{2}(2 x-h)+\frac{1 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 4} h^2(2 x-h)^2+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6} h^3(2 x-h)^3+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \cdot 7}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6 \cdot 8} h^4(2 x-h)^4+….\)

⇒ \(P_0(x)+h P_1(x)+h^2 P_2(x)+h^3 P_3(x)+h^4 P_4(x)+\cdots\)

⇒ \(1+x h+\frac{1}{2}\left(3 x^2-1\right) h^2+\frac{1}{2}\left(5 x^3-3 x\right) h^3+\frac{1}{8}\left(35 x^4-30 x^2+3\right) h^4+\cdots\)

Equating the coefficient of like powers of h, we have P0(x) = 1, P1(x) = x,

⇒ \(P_2(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(3 x^2-1\right), P_3(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(5 x^3-3 x\right), P_4(x)=\frac{1}{8}\left(35 x^4-30 x^2+3\right)\)

Legendre polynomials orthogonality property with examples

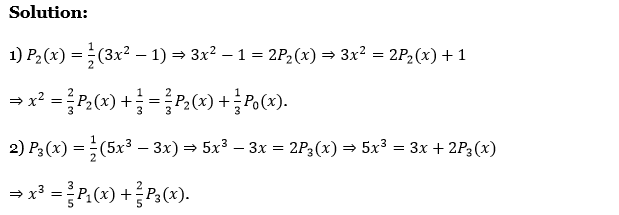

6. Prove that, for all x 1) \(x^2=\frac{1}{3} P_0(x)+\frac{2}{3} P_2(x)\) 2) \(x^3=\frac{3}{5} P_1(x)+\frac{2}{5} P_2(x)\).

Solution:

1. \(P_2(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(3 x^2-1\right) \Rightarrow 3 x^2-1=2 P_2(x) \Rightarrow 3 x^2=2 P_2(x)+1\)

⇒ \(x^2=\frac{2}{3} P_2(x)+\frac{1}{3}=\frac{2}{3} P_2(x)+\frac{1}{3} P_0(x)\)

2. \(P_3(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(5 x^3-3 x\right) \Rightarrow 5 x^3-3 x=2 P_3(x) \Rightarrow 5 x^3=3 x+2 P_3(x)\)

⇒ \(x^3=\frac{3}{5} P_1(x)+\frac{2}{5} P_3(x)\)

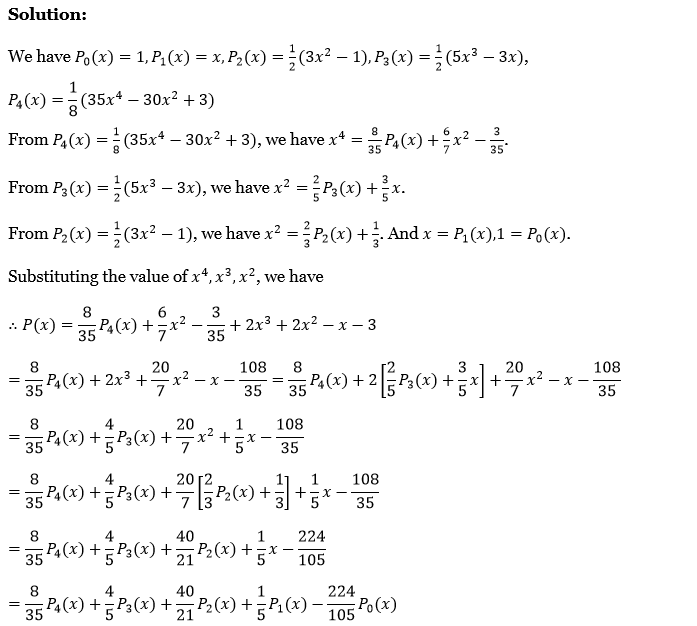

7. Express \(P(x)=x^4+2 x^3+2 x^2-x-3\) in terms of Legendre’s polynomials.

Solution:

We have, \(P_0(x)=1, P_1(x)=x, P_2(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(3 x^2-1\right), P_3(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(5 x^3-3 x\right)\)

⇒ \(P_4(x)=\frac{1}{8}\left(35 x^4-30 x^2+3\right)\)

From \(P_4(x)=\frac{1}{8}\left(35 x^4-30 x^2+3\right), \text { we have } x^4=\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+\frac{6}{7} x^2-\frac{3}{35}\)

From \(P_3(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(5 x^3-3 x\right) \text {, we have } x^2=\frac{2}{5} P_3(x)+\frac{3}{5} x\)

From \(P_2(x)=\frac{1}{2}\left(3 x^2-1\right) \text {, we have } x^2=\frac{2}{3} P_2(x)+\frac{1}{3} \text {. And } x=P_1(x), 1=P_0(x) \text {. }\)

Substituting the value of \(x^4, x^3, x^2\), we have

∴ \(P(x)=\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+\frac{6}{7} x^2-\frac{3}{35}+2 x^3+2 x^2-x-3\)

⇒ \(\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+2 x^3+\frac{20}{7} x^2-x-\frac{108}{35}=\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+2\left[\frac{2}{5} P_3(x)+\frac{3}{5} x\right]+\frac{20}{7} x^2-x-\frac{108}{35}\)

⇒ \(\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+\frac{4}{5} P_3(x)+\frac{20}{7} x^2+\frac{1}{5} x-\frac{108}{35}\)

⇒ \(\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+\frac{4}{5} P_3(x)+\frac{20}{7}\left[\frac{2}{3} P_2(x)+\frac{1}{3}\right]+\frac{1}{5} x-\frac{108}{35}\)

⇒ \(\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+\frac{4}{5} P_3(x)+\frac{40}{21} P_2(x)+\frac{1}{5} x-\frac{224}{105}\)

⇒ \(=\frac{8}{35} P_4(x)+\frac{4}{5} P_3(x)+\frac{40}{21} P_2(x)+\frac{1}{5} P_1(x)-\frac{224}{105} P_0(x)\)

Step-By-Step Solutions For Legendre Polynomial Exercises

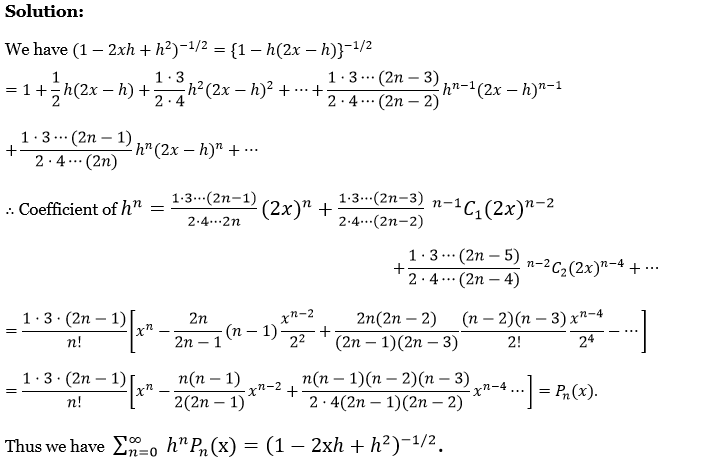

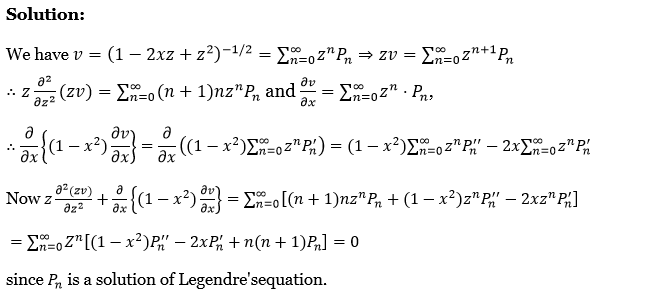

8. Prove that \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)\).

Solution:

We have \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\{1-h(2 x-h)\}^{-1 / 2}\)

⇒ \(1+\frac{1}{2} h(2 x-h)+\frac{1 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 4} h^2(2 x-h)^2+\cdots+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n-3)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdots(2 n-2)} h^{n-1}(2 x-h)^{n-1}+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n-1)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdots(2 n)} h^n(2 x-h)^n+\cdots\)

∴ Coefficient of \(h^n=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n-1)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdots 2 n}(2 x)^n+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n-3)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdots(2 n-2)}{ }^{n-1} C_1(2 x)^{n-2}\)

⇒ \(+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n-5)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdots(2 n-4)}{ }^{n-2} C_2(2 x)^{n-4}+\cdots\)

⇒ \(\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot(2 n-1)}{n!}\left[x^n-\frac{2 n}{2 n-1}(n-1) \frac{x^{n-2}}{2^2}+\frac{2 n(2 n-2)}{(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} \frac{(n-2)(n-3)}{2!} \frac{x^{n-4}}{2^4}-\cdots\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot(2 n-1)}{n!}\left[x^n-\frac{n(n-1)}{2(2 n-1)} x^{n-2}+\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4(2 n-1)(2 n-2)} x^{n-4} \cdots\right]=P_n(x)\)

Thus we have \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(\mathrm{x})=\left(1-2 \mathrm{x} h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}\)

Examples Of Generating Functions For Legendre Polynomials

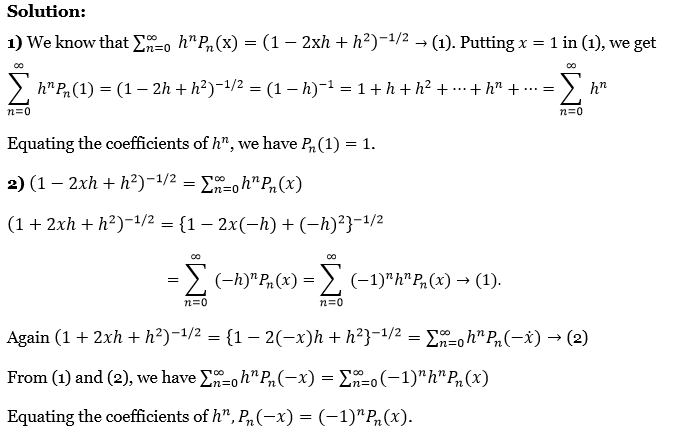

9. Show that 1) \(P_n(1)=1\) 2) \(P_n(-x)=(-1)^n P_n(x)\) and hence deduce that \(P_n(-1)=(-1)^n\).

Solution:

1. We know that \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(\mathrm{x})=\left(1-2 \mathrm{x} h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2} \rightarrow(1)\)

Putting x = 1 in (1), we get

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(1)=\left(1-2 h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=(1-h)^{-1}=1+h+h^2+\cdots+h^n+\cdots=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n\)

Equation the coefficient of hn, we have Pn(1) = 1

2. \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)\)

⇒ \(\left(1+2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\left\{1-2 x(-h)+(-h)^2\right\}^{-1 / 2}\)

⇒ \(=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(-h)^n P_n(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(-1)^n h^n P_n(x) \rightarrow(1)\)

Again \(\left(1+2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\left\{1-2(-x) h+h^2\right\}^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(-{x}) \rightarrow(2)\)

From (1) and (2), we have \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(-x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(-1)^n h^n P_n(x)\)

Equating the coefficient of \(h^n, P_n(-x)=(-1)^n P_n(x)\)

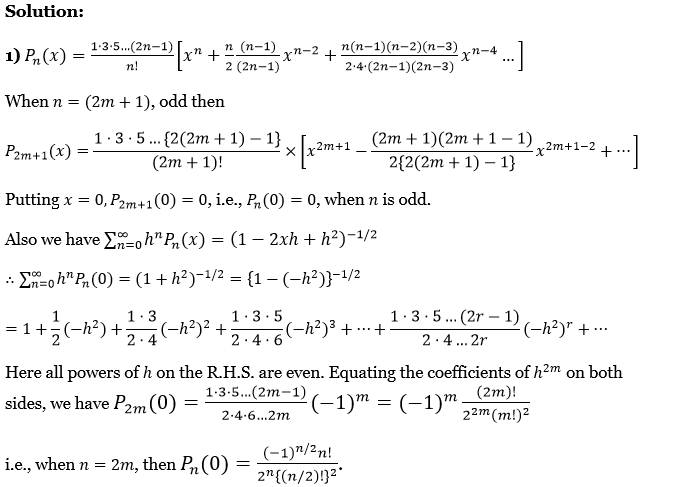

10. Prove that \(P_n(0)=0\), for n odd and \(P_n(0)=\frac{(-1)^{n / 2} n !}{2^n\{(n / 2) !\}^2}\), for n even.

Solution:

1. \(P_n(x)=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \ldots(2 n-1)}{n!}\left[x^n+\frac{n}{2} \frac{(n-1)}{(2 n-1)} x^{n-2}+\frac{n(n-1)(n-2)(n-3)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot(2 n-1)(2 n-3)} x^{n-4} \ldots\right]\)

When n = (2m+1), odd then

⇒ \(P_{2 m+1}(x)=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \ldots\{2(2 m+1)-1\}}{(2 m+1)!} \times\left[x^{2 m+1}-\frac{(2 m+1)(2 m+1-1)}{2\{2(2 m+1)-1\}} x^{2 m+1-2}+\cdots\right]\)

Putting \(x=0, P_{2 m+1}(0)=0 \text {, i.e., } P_n(0)=0\), when n is odd.

Also, we have \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)=\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}\)

∴ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(0)=\left(1+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\left\{1-\left(-h^2\right)\right\}^{-1 / 2}\)

⇒ \(1+\frac{1}{2}\left(-h^2\right)+\frac{1 \cdot 3}{2 \cdot 4}\left(-h^2\right)^2+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6}\left(-h^2\right)^3+\cdots+\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \ldots(2 r-1)}{2 \cdot 4 \ldots 2 r}\left(-h^2\right)^r+\cdots\)

Here all powers of h on the R.H.S. are even. Equating the coefficients of h2m on both sides, we have

⇒ \(P_{2 m}(0)=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdot 5 \ldots(2 m-1)}{2 \cdot 4 \cdot 6 \ldots . .2 m}(-1)^m=(-1)^m \frac{(2 m)!}{2^{2 m}(m!)^2}\)

i.e., when n = 2m, then \(\)

⇒ \(P_n(0)=\frac{(-1)^{n / 2} n!}{2^n\{(n / 2)!\}^2}\)

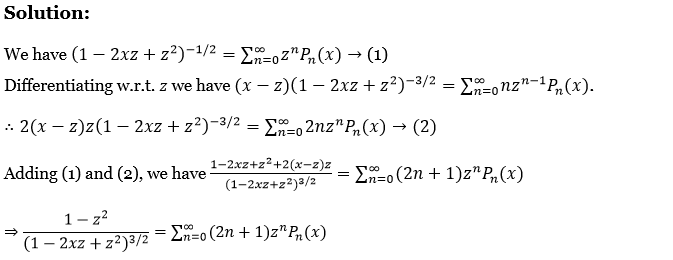

11. Prove that \(\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}\) is a solution of the equation of \(z \frac{\partial^2(z v)}{\partial z^2}+\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\right\}=0\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\frac{1+z}{z \sqrt{\left\{\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)\right\}}}-\frac{1}{z}=\frac{1}{z}\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}+\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}-\frac{1}{z}\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{z} \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)-\frac{1}{z}=\frac{1}{z}\left[P_0(x)+\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)\right]+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^{\prime \prime} P_n(x)-\frac{1}{z}\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{z}+\frac{1}{z} \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)-\frac{1}{z} \text { since } P_0(x)=1\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} z^{n-1} P_n(x)+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_{n+1}(x)+\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\left[P_{n+1}(x)+P_n(x)\right] z^n\)

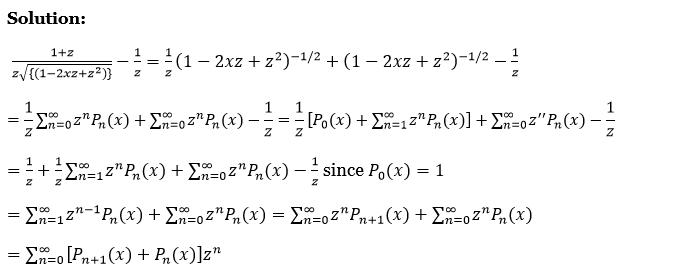

12. Prove that \(\frac{1+z}{z \sqrt{\left.\left\{1-2 x z+z^2\right)\right\}}}-\frac{1}{z}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\left[P_n(x)+P_{n+1}(x)\right] z^n\).

Solution:

We have \(\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x) \rightarrow(1)\)

Differentiating w.r.t. z we have \((x-z)\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-3 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n z^{n-1} P_n(x)\)

∴ \(2(x-z) z\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-3 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} 2 n z^n P_n(x) \rightarrow(2)\)

Adding (1) and (2), we have \(\frac{1-2 x z+z^2+2(x-z) z}{\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{3 / 2}}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(2 n+1) z^n P_n(x)\)

⇒ \(\frac{1-z^2}{\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{3 / 2}}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(2 n+1) z^n P_n(x)\)

13. Show that \(\frac{1-z^2}{\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{3 / 2}}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(2 n+1) z^n P_n(x)\).

Solution:

We have v = \(\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n \Rightarrow z v=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^{n+1} P_n\)

∴ \(z \frac{\partial^2}{\partial z^2}(z v)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}(n+1) n z^n P_n \text { and } \frac{\partial v}{\partial x}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n \cdot P_n\)

∴ \(\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\right\}=\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(\left(1-x^2\right) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n^{\prime}\right)=\left(1-x^2\right) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n^{\prime \prime}-2 x \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n^{\prime}\)

Now \(z \frac{\partial^2(z v)}{\partial z^2}+\frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{\partial v}{\partial x}\right\}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty}\left[(n+1) n z^n P_n+\left(1-x^2\right) z^n P_n^{\prime \prime}-2 x z^n P_n^{\prime}\right]\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} Z^n\left[\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime \prime}-2 x P_n^{\prime}+n(n+1) P_n\right]=0\)

since Pn is a solution of Legendre’s equation

Worked Problems On Legendre Polynomial Recursion Relations

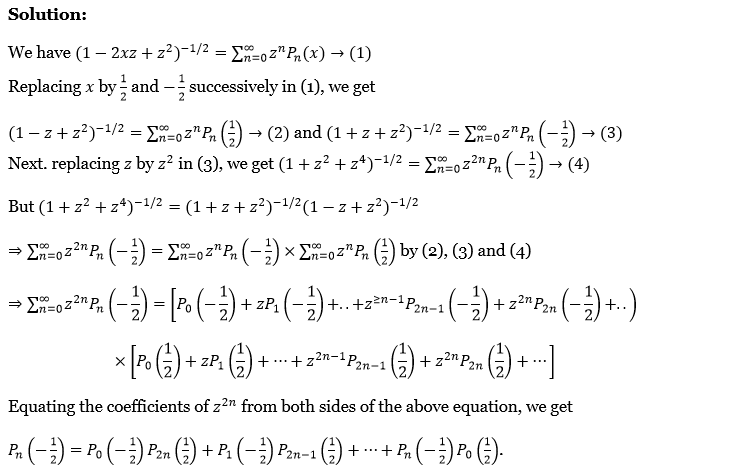

14. Prove that \(P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=P_0\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) P_{2 n}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+P_1\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) P_{2 n-1}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+\ldots+P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) P_0\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\).

Solution:

We have \(\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x) \rightarrow(1)\)

Replacing x by \(\frac{1}{2} \text { and }-\frac{1}{2}\) successively in (1), we get

⇒ \(\left(1-z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n\left(\frac{1}{2}\right) \rightarrow \text { (2) and }\left(1+z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) \rightarrow \text { (3) }\)

Next replacing z by z2 in (3), we get \(\left(1+z^2+z^4\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^{2 n} P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) \rightarrow(4)\)

But \(\left(1+z^2+z^4\right)^{-1 / 2}=\left(1+z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}\left(1-z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2}\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^{2 n} P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) \times \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n\left(\frac{1}{2}\right) \text { by (2), (3) and (4) }\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^{2 n} P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=\left[P_0\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)+z P_1\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)+. .+z^{\geq n-1} P_{2 n-1}\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)+z^{2 n} P_{2 n}\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)+. .\right)\)

⇒ \(\times\left[P_0\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+z P_1\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+\cdots+z^{2 n-1} P_{2 n-1}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+z^{2 n} P_{2 n}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+\cdots\right]\)

Equating the coefficients of z2n from both sides of the above equation, we get

⇒ \(P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)=P_0\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) P_{2 n}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+P_1\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) P_{2 n-1}\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)+\cdots+P_n\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) P_0\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)\)

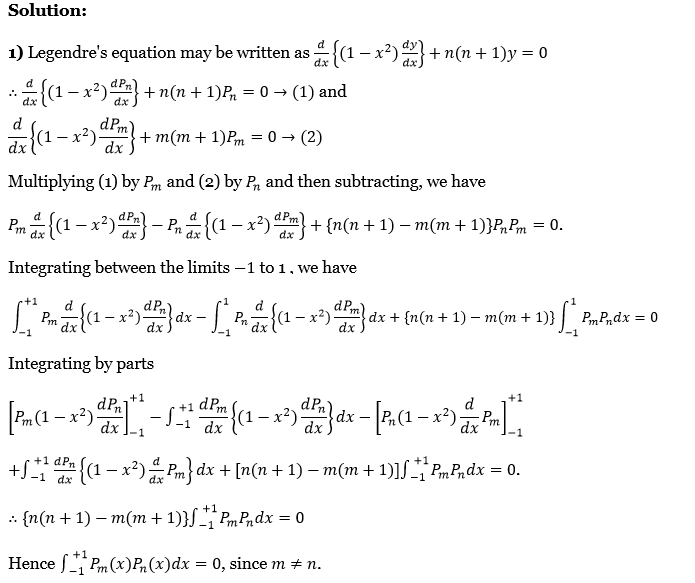

15. Prove that 1) \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_{m t}(x) P_n(x) d x=0 \text { if } m \neq n\) 2) \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left[P_n(x)\right]^2 d x=\frac{2}{2 n+1}\).

Solution:

1. Legendre’s equation may be written as \(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d y}{d x}\right\}+n(n+1) y=0\)

∴ \(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_n}{d x}\right\}+n(n+1) P_n=0 \rightarrow(1)\) and

\(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_m}{d x}\right\}+m(m+1) P_m=0 \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)Multiplying (1) by Pm and (2) by Pn and then subtracting, we have

⇒ \(P_m \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_n}{d x}\right\}-P_n \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_m}{d x}\right\}+\{n(n+1)-m(m+1)\} P_n P_m=0\)

Integrating between the limits -1 to 1, we have

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_m \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_n}{d x}\right\} d x-\int_{-1}^1 P_n \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_m}{d x}\right\} d x+\{n(n+1)-m(m+1)\} \int_{-1}^1 P_m P_n d x=0\)

Integrating by parts

⇒ \(\left[P_m\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_n}{d x}\right]_{-1}^{+1}-\int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{d P_m}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d P_n}{d x}\right\} d x-\left[P_n\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d}{d x} P_m\right]_{-1}^{+1}\)

⇒ \(+\int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{d P_n}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d}{d x} P_m\right\} d x+[n(n+1)-m(m+1)] \int_{-1}^{+1} P_m P_n d x=0\)

∴ \(\{n(n+1)-m(m+1)\} \int_{-1}^{+1} P_m P_n d x=0\)

Hence \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_m(x) P_n(x) d x=0\) since m ≠ n

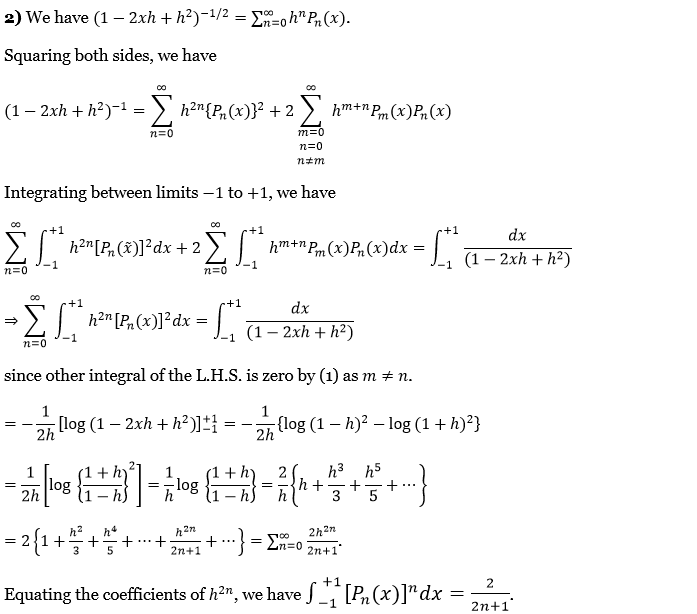

2. we have \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)\)

Squaring both sides we have

⇒ \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^{2 n}\left\{P_n(x)\right\}^2+2 \sum_{{m=0 \\ n=0 \\ n \neq m}}^{\infty} h^{m+n} P_m(x) P_n(x)\)

Integrating between limits -1 to +1, we have

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{-1}^{+1} h^{2 n}\left[P_n(\tilde{x})\right]^2 d x+2 \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{-1}^{+1} h^{m+n} P_m(x) P_n(x) d x=\int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{d x}{\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)}\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_{-1}^{+1} h^{2 n}\left[P_n(x)\right]^2 d x=\int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{d x}{\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)}\)

Since the other integral of the L.H.S. is zero by (1) as m ≠ n

⇒ \(-\frac{1}{2 h}\left[\log \left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)\right]_{-1}^{+1}=-\frac{1}{2 h}\left\{\log (1-h)^2-\log (1+h)^2\right\}\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2 h}\left[\log \left\{\frac{1+h}{1-h}\right\}^2\right]=\frac{1}{h} \log \left\{\frac{1+h}{1-h}\right\}=\frac{2}{h}\left\{h+\frac{h^3}{3}+\frac{h^5}{5}+\cdots\right\}\)

⇒ \(2\left\{1+\frac{h^2}{3}+\frac{h^4}{5}+\cdots+\frac{h^{2 n}}{2 n+1}+\cdots\right\}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{2 h^{2 n}}{2 n+1} .\)

Equating the coefficients of h2n, we have \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left[P_n(x)\right]^n d x=\frac{2}{2 n+1}\)

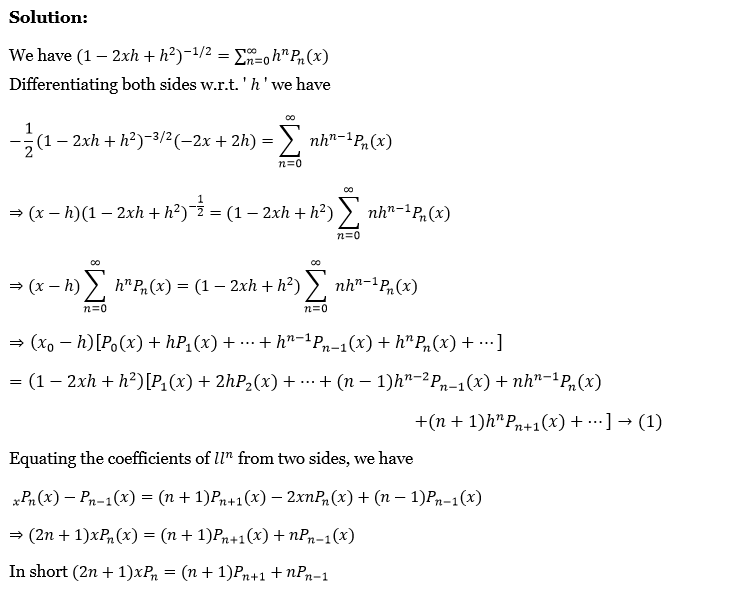

16. Prove that \((2 n+1) x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1} \text {. }\).

Solution:

We have \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)\)

Differentiating both sides w.r.t ‘h’ we have

⇒ \(-\frac{1}{2}\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-3 / 2}(-2 x+2 h)=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n h^{n-1} P_n(x)\)

⇒ \((x-h)\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-\frac{1}{2}}=\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n h^{n-1} P_n(x)\)

⇒ \((x-h) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x)=\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n h^{n-1} P_n(x)\)

⇒ \(\left(x_0-h\right)\left[P_0(x)+h P_1(x)+\cdots+h^{n-1} P_{n-1}(x)+h^n P_n(x)+\cdots\right]\)

⇒ \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)\left[P_1(x)+2 h P_2(x)+\cdots+(n-1) h^{n-2} P_{n-1}(x)+n h^{n-1} P_n(x)\right.\)

⇒ \(\left.+(n+1) h^n P_{n+1}(x)+\cdots\right] \rightarrow(1)\)

Equating the coefficient of lln from two sides, we have

⇒ \({ }_x P_n(x)-P_{n-1}(x)=(n+1) P_{n+1}(x)-2 x n P_n(x)+(n-1) P_{n-1}(x)\)

⇒ \((2 n+1) x P_n(x)=(n+1) P_{n+1}(x)+n P_{n-1}(x)\)

In short \((2 n+1) x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}\)

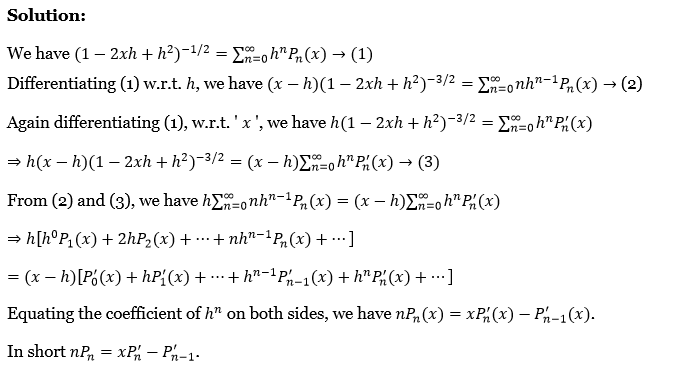

17. Prove that \(n P_n=x P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\).

Solution:

We have \(\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-1 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n(x) \rightarrow(1)\)

Differentiating (1) w.r.t. h, we have \((x-h)\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-3 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n h^{n-1} P_n(x) \rightarrow(2)\)

Again differentiating (1), we have \(h\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-3 / 2}=\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n^{\prime}(x)\)

⇒ \(h(x-h)\left(1-2 x h+h^2\right)^{-3 / 2}=(x-h) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n^{\prime}(x) \rightarrow(3)\)

From (2) and (3), we have \(h \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} n h^{n-1} P_n(x)=(x-h) \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} h^n P_n^{\prime}(x)\)

⇒ \(h\left[h^0 P_1(x)+2 h P_2(x)+\cdots+n h^{n-1} P_n(x)+\cdots\right]\)

⇒ \((x-h)\left[P_0^{\prime}(x)+h P_1^{\prime}(x)+\cdots+h^{n-1} P_{n-1}^{\prime}(x)+h^n P_n^{\prime}(x)+\cdots\right]\)

Equating the coefficient of hn on both sides, we have \(n P_n(x)=x P_n^{\prime}(x)-P_{n-1}^{\prime}(x)\)

In short \(n P_n=x P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

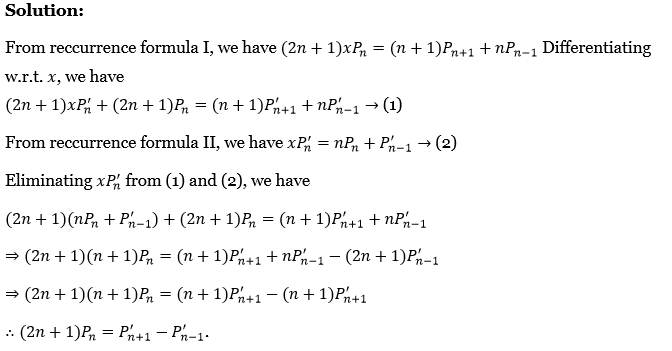

18. Prove that \((2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\).

Solution:

From recurrence formula 1, we have \((2 n+1) x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}\) Differentiating w.r.t we have

⇒ \((2 n+1) x P_n^{\prime}+(2 n+1) P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}^{\prime}+n P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow(1)\)

From recurrence formula 2, we have\(x P_n^{\prime}=n P_n+P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)

Eliminating xP’n From (1) and (2), we have

⇒ \((2 n+1)\left(n P_n+P_{n-1}^{\prime}\right)+(2 n+1) P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}^{\prime}+n P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

⇒ \((2 n+1)(n+1) P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}^{\prime}+n P_{n-1}^{\prime}-(2 n+1) P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

⇒ \((2 n+1)(n+1) P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}^{\prime}-(n+1) P_{n+1}^{\prime}\)

∴ \((2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

19. Prove that \((n+1) P_n=\left(P_{n+1}^{\prime}-x P_n^{\prime}\right)\).

Solution:

Writing Recurrence formula | and || we have,

⇒ \(n P_n=x P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow(1) \text { and }(2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)

Subtracting (1) from (2) we have \((n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-x P_n^{\prime}\)

20. Prove that \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=n\left(P_{n-1}-x P_n\right)\).

Solution:

Replacing n by (n-1) in recurrence formula IV, we have

⇒ \(n P_{n-1}=P_n^{\prime}-x P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow(1)\)

Writing II recurrence formula, we have \(n P_n=x P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow(2)\)

Multiplying by x and then subtracting from (1), we have

⇒ \(n\left(P_{n-1}-x P_n\right)=\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime} \Rightarrow\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=n\left(P_{n-1}-x P_n\right)\)

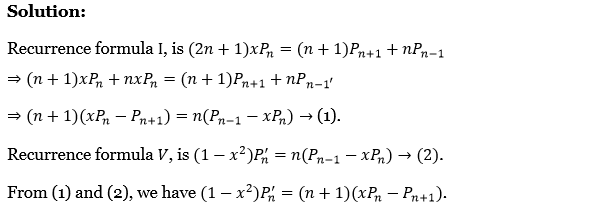

21. Prove that \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=(n+1)\left(x P_n-P_{n+1}\right)\).

Solution:

Recurrence formula 1, is \((2 n+1) x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}\)

⇒ \((n+1) x P_n+n x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1^{\prime}}\)

⇒ \((n+1)\left(x P_n-P_{n+1}\right)=n\left(P_{n-1}-x P_n\right) \rightarrow(1)\)

Recurrence formula V is \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=n\left(P_{n-1}-x P_n\right) \rightarrow(2)\)

From (1) and (2), we have \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=(n+1)\left(x P_n-P_{n+1}\right)\)

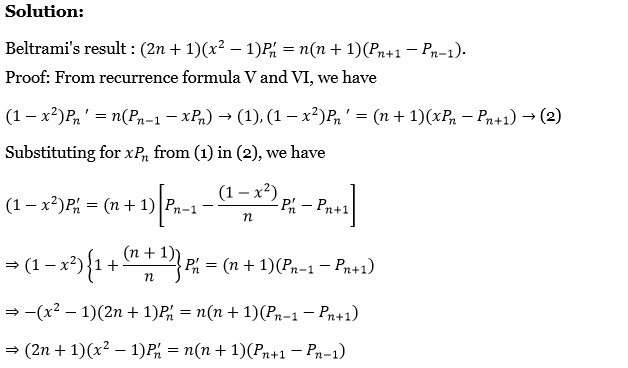

22. Prove Beltrami’s result. i.e., \((2 n+1)\left(x^2-1\right) P_n^{\prime}=n(n+1)\left(P_{n+1}-P_{n-1}\right)\).

Solution:

Beltrami’s result: \((2 n+1)\left(x^2-1\right) P_n^{\prime}=n(n+1)\left(P_{n+1}-P_{n-1}\right)\)

Proof: From recurrence formulas 5 and 6, we have

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=n\left(P_{n-1}-x P_n\right) \rightarrow(1),\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=(n+1)\left(x P_n-P_{n+1}\right) \rightarrow(2)\)

Substituting for xPn from (1) in (2), we have

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=(n+1)\left[P_{n-1}-\frac{\left(1-x^2\right)}{n} P_n^{\prime}-P_{n+1}\right]\)

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right)\left\{1+\frac{(n+1)}{n}\right\} P_n^{\prime}=(n+1)\left(P_{n-1}-P_{n+1}\right)\)

⇒ \(-\left(x^2-1\right)(2 n+1) P_n^{\prime}=n(n+1)\left(P_{n-1}-P_{n+1}\right)\)

⇒ \((2 n+1)\left(x^2-1\right) P_n^{\prime}=n(n+1)\left(P_{n+1}-P_{n-1}\right)\)

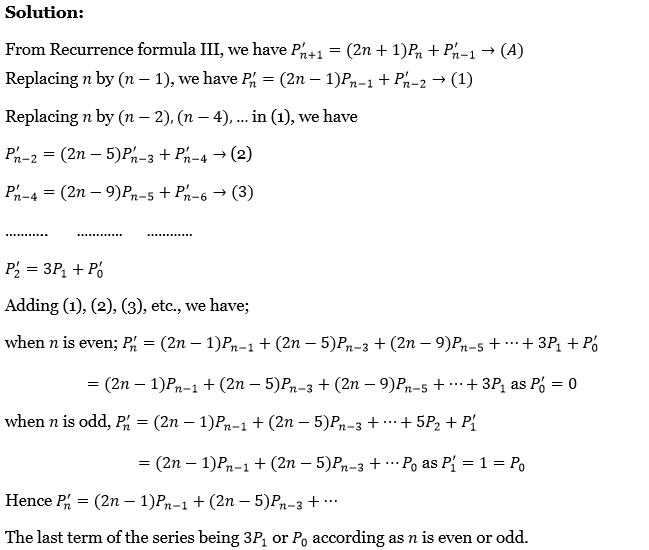

23. Prove that \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+(2 n-9) P_{n-5}+\ldots\), the last term of the series being \(3 P_1 \text { or } P_0\) according as n is even or odd.

Solution:

From Recurrence formula 3, we have \(P_{n+1}^{\prime}=(2 n+1) P_n+P_{n-1}^{\prime} \rightarrow(A)\)

Replacing n by (n-1) we have \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+P_{n-2}^{\prime} \rightarrow(1)\)

Replacing n by (n-1) (n-4),…….. in (1), we have

⇒ \(P_{n-2}^{\prime}=(2 n-5) P_{n-3}^{\prime}+P_{n-4}^{\prime} \rightarrow(2)\)

⇒ \(P_{n-4}^{\prime}=(2 n-9) P_{n-5}+P_{n-6}^{\prime} \rightarrow(3)\)

……… ……… …….

⇒ \(P_2^{\prime}=3 P_1+P_0^{\prime}\)

Adding (1),(2),(3), etc., we have;

when n is even; \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+(2 n-9) P_{n-5}+\cdots+3 P_1+P_0^{\prime}\)

⇒ \((2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+(2 n-9) P_{n-5}+\cdots+3 P_1 \text { as } P_0^{\prime}=0\)

When n is odd, \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+\cdots+5 P_2+P_1^{\prime}\)

⇒ \((2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+\cdots P_0 \text { as } P_1^{\prime}=1=P_0\)

Hence \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+\cdots\)

The last term of the series 3P1 or P0 according to n is even or odd.

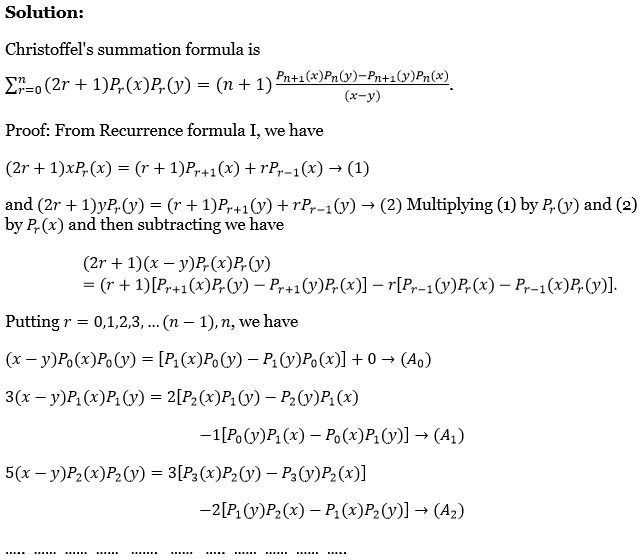

24. Prove Christoffel’s summation formula :

\(\sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x) P_r(y)=(n+1) \frac{P_{n+1}(x) P_n(y)-P_{n+1}(y) P_n(x)}{(x-y)} .\)

Solution:

Christoffel’s summation formula is

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x) P_r(y)=(n+1) \frac{P_{n+1}(x) P_n(y)-P_{n+1}(y) P_n(x)}{(x-y)}\)

Proof: From Recurrence formula 1, we have

⇒ \((2 r+1) x P_r(x)=(r+1) P_{r+1}(x)+r P_{r-1}(x) \rightarrow(1)\)

and \((2 r+1) y P_r(y)=(r+1) P_{r+1}(y)+r P_{r-1}(y) \rightarrow(2)\) Multiplying (1) by Pr(y) and (2) by Pr(x) and then subtracting we have

⇒ \((2 r+1)(x-y) P_r(x) P_r(y)\) = \((r+1)\left[P_{r+1}(x) P_r(y)-P_{r+1}(y) P_r(x)\right]-r\left[P_{r-1}(y) P_r(x)-P_{r-1}(x) P_r(y)\right]\)

Putting r = 0,1,2,3, ….. (n-1), n, we have

⇒ \((x-y) P_0(x) P_0(y)=\left[P_1(x) P_0(y)-P_1(y) P_0(x)\right]+0 \rightarrow\left(A_0\right)\)

⇒ \(3(x-y) P_1(x) P_1(y)=2\left[P_2(x) P_1(y)-P_2(y) P_1(x)\right.\)

⇒ \(-1\left[P_0(y) P_1(x)-P_0(x) P_1(y)\right] \rightarrow\left(A_1\right)\)

⇒ \(5(x-y) P_2(x) P_2(y)=3\left[P_3(x) P_2(y)-P_3(y) P_2(x)\right]\)

⇒ \(-2\left[P_1(y) P_2(x)-P_1(x) P_2(y)\right] \rightarrow\left(A_2\right)\)

………… …………… …………..

….. ……. …… …… …….. ……. …….. …… ……

⇒ \((2 n-1)(x-y) P_{n-1}(x) P_{n-1}(y)=n\left[P_n(x) P_{n-1}(y)-P_n(y) P_{n-1}(x)\right]\)

⇒ \(-(n-1)\left[P_{n-2}(y) P_{n-1}(x)-P_{n-2}(x) P_{n-1}(y)\right] \rightarrow\left(A_{n-1}\right)\)

⇒ \((2 n+1)(x-y) P_n(x) P_n(y)=(n+1)\left[P_{n+1}(x) P_n(y)-P_{n+1}(y) P_n^r(x)\right]\)

⇒ \(-n\left[P_{n-1}(y) P_n(x)-P_{n-1}(x) P_n(y)\right] \rightarrow\left(A_n\right)\)

Adding \(\left(A_0\right),\left(A_1\right),\left(A_2\right) \ldots\left(A_{n-1}\right) \text { and }\left(A_n\right)\) we have

⇒ \((x-y) \sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x) P_r(y)=(n+1)\left[P_{n+1}(x) P_n(y)-P_{n+1}(y) P_{n^0}(x)\right]\)

Hence \(\sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x) P_r(y)=(n+1) \frac{P_{n+1}(x) P_n(y)-P_{n+1}(y) P_n(x)}{(x-y)}\)

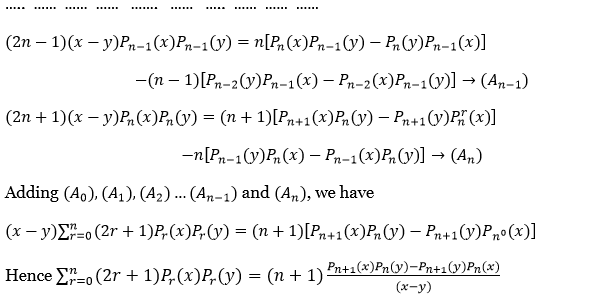

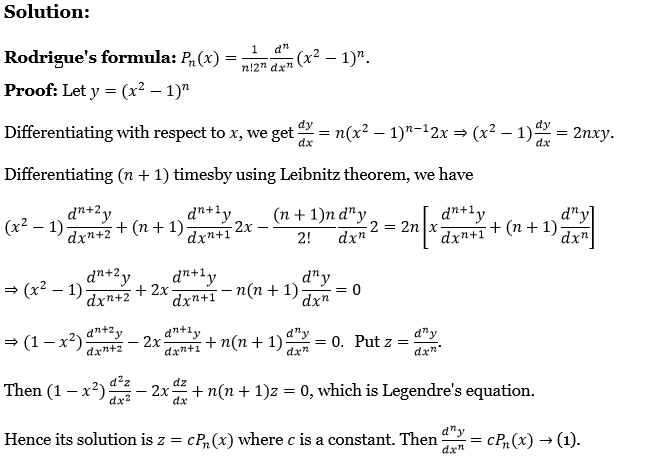

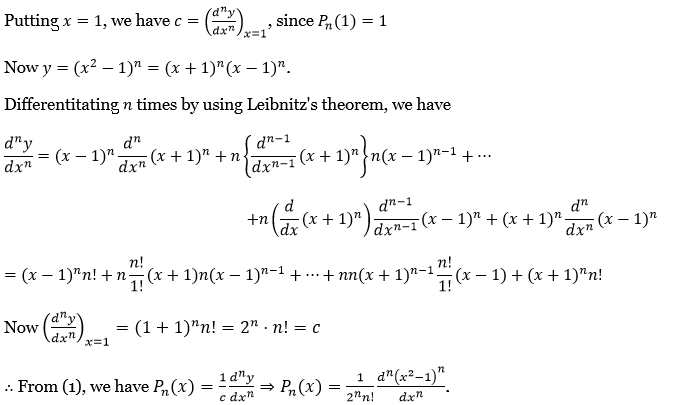

25. Prove Rodrigue’s formula : \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{n ! 2^n} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\)

Solution:

Rodrigue”s formula: \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{n!2^n} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\)

Proof: Let y = \(\left(x^2-1\right)^n\)

Differentiating with respect to x, we get \(\frac{d y}{d x}=n\left(x^2-1\right)^{n-1} 2 x \Rightarrow\left(x^2-1\right) \frac{d y}{d x}=2 n x y\)

Differentiating (n+10 times by using the Leibnitz theorem, we have

⇒ \(\left(x^2-1\right) \frac{d^{n+2} y}{d x^{n+2}}+(n+1) \frac{d^{n+1} y}{d x^{n+1}} 2 x-\frac{(n+1) n}{2!} \frac{d^n y}{d x^n} 2=2 n\left[x \frac{d^{n+1} y}{d x^{n+1}}+(n+1) \frac{d^n y}{d x^n}\right]\)

⇒ \(\left(x^2-1\right) \frac{d^{n+2} y}{d x^{n+2}}+2 x \frac{d^{n+1} y}{d x^{n+1}}-n(n+1) \frac{d^n y}{d x^n}=0\)

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^{n+2} y}{d x^{n+2}}-2 x \frac{d^{n+1} y}{d x^{n+1}}+n(n+1) \frac{d^n y}{d x^n}=0\)

Put z= \(\frac{d^n y}{d x^n}\)

Then \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^2 z}{x^2}-2 x \frac{d z}{2}+n(n+1) z=0\) which is Legendre’s equation.

Hence its solution is z = cPn(x) where c is a constant. Then \(\frac{d^n y}{d x^n}=c P_n(x) \rightarrow(1)\)

Putting x = 1, we have c = \(\left(\frac{d^n y}{d x^n}\right)_{x=1}\), since \(P_n(1)=1\)

Now \(y=\left(x^2-1\right)^n=(x+1)^n(x-1)^n\)

Differentiating n times by using Leibnitz’s theorem, we have

⇒ \(\frac{d^n y}{d x^n}=(x-1)^n \frac{d^n}{d x^n}(x+1)^n+n\left\{\frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}(x+1)^n\right\} n(x-1)^{n-1}+\cdots\)

⇒ \(+n\left(\frac{d}{d x}(x+1)^n\right) \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}(x-1)^n+(x+1)^n \frac{d^n}{d x^n}(x-1)^n\)

⇒ \((x-1)^n n!+n \frac{n!}{1!}(x+1) n(x-1)^{n-1}+\cdots+n n(x+1)^{n-1} \frac{n!}{1!}(x-1)+(x+1)^n n!\)

Now \(\left(\frac{d^n y}{d x^n}\right)_{x=1}=(1+1)^n n!=2^n \cdot n!=c\)

∴ From (1), we have \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{c} \frac{d^n y}{d x^n} \Rightarrow P_n(x)=\frac{1}{2^n n!} \frac{d^n\left(x^2-1\right)^n}{d x^n}\)

26. Prove that \(P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-2}^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}\).

Solution: \(\text { Recurrence formula III, is }(2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

⇒ \(\text { Replacing } n \text { by n-1} \text {, we get }(2 n-1) P_n=P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-2}^{\prime} \text {. }\)

27. Prove that \(x P_9^{\prime}=P_8^{\prime}-2 P_9\).

Solution: \(\text { Recurrence formula II is } n P_n^{\prime}=x P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

⇒ \(\text { Putting } n=9 \text {, we get } 9 P_9=x P_9^{\prime}-P_8^{\prime} \Rightarrow x P_9^{\prime}=9 P_9+P_8^{\prime} \text {. }\)

28. Prove that \(\frac{P_{n+1}-P_{n-1}}{2 n+1}=\int P_n d x+c\).

Solution: From the recurrence formula |||, we have

⇒ \((2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime} \Rightarrow \frac{\left(P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\right)}{2 n+1}=P_n\)

⇒ \(\text { Integrating, } \frac{P_{n+1}-P_{n-1}}{2 n+1}=\int P_n d x+c\)

29. Show that \(11\left(x^2-1\right) P_5^{\prime}=30\left(P_6-P_4\right)\).

Solution: Beltrami,s result is \((2 n+1)\left(x^2-1\right) P_n^{\prime}=n(n+1)\left(P_{n+1}-P_{n-1}\right)\)

⇒ \(\text { Putting } n=5 \text {, we get } 11\left(x^2-1\right) P_5^{\prime}=30\left(P_6-P_4\right)\)

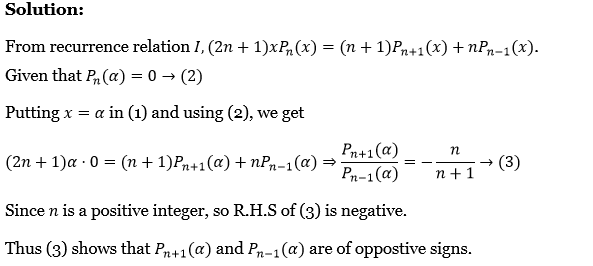

30. If \(P_n(x)\) is a Legendre polynomial of degree n and α is such that \(P_n(\alpha)=0\), then show that \(P_{n-1}(\alpha) \text { and } P_{n+1}(\alpha)\) are of opposite signs.

Solution:

From recurrence relation \(I,(2 n+1) x P_n(x)=(n+1) P_{n+1}(x)+n P_{n-1}(x)\)

Given that \(P_n(\alpha)=0 \rightarrow(2)\)

Putting x = a in (1) and using (2), we get

⇒ \((2 n+1) \alpha \cdot 0=(n+1) P_{n+1}(\alpha)+n P_{n-1}(\alpha) \Rightarrow \frac{P_{n+1}(\alpha)}{P_{n-1}(\alpha)}=-\frac{n}{n+1} \rightarrow \text { (3) }\)

Since n is a positive integer, the R.H.S of (3) is negative.

Thus (3) shows that Pn+1(α) and Pn-1(α) are of opposite signs.

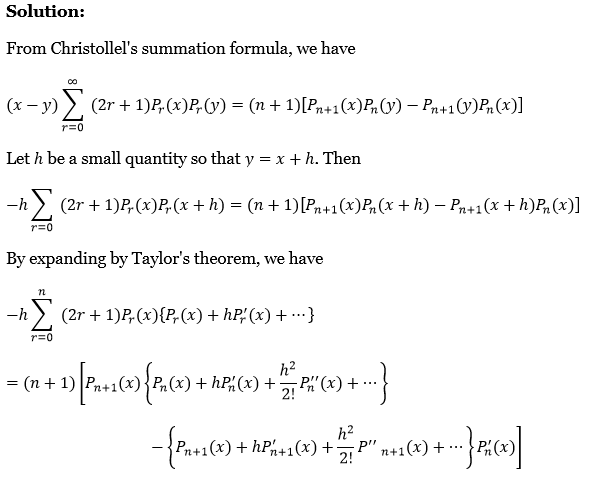

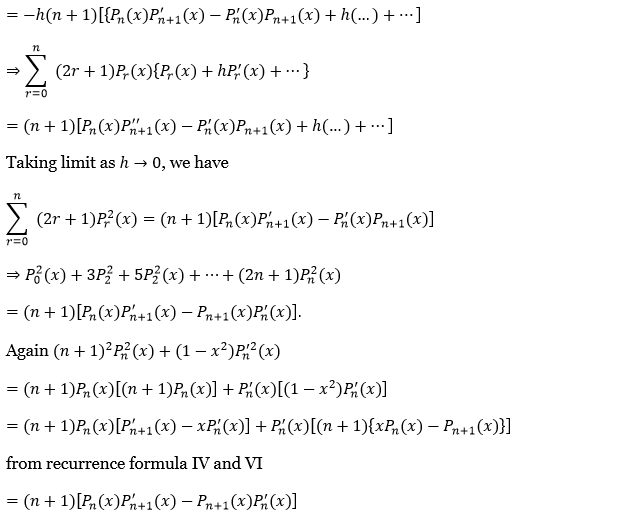

31. Prove that \(P_0^2(x)+3 P_1^2(x)+5 P_2^2(x)+\ldots+(2 n+1) P_n^2(x)\)

⇒ \(=(n+1)\left[P_n(x) P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_{n+1}(x) P_n^{\prime}(x)\right]=(n+1)^2 P_n^2(x)+\left(1-x^2\right)\left\{P_n^{\prime}(x)\right\}^2\)

Solution:

From Christollel’s summation formula, we have

⇒ \((x-y) \sum_{r=0}^{\infty}(2 r+1) P_r(x) P_r(y)=(n+1)\left[P_{n+1}(x) P_n(y)-P_{n+1}(y) P_n(x)\right]\)

Let h be a small quantity so that y = x+h. Then

⇒ \(-h \sum_{r=0}(2 r+1) P_r(x) P_r(x+h)=(n+1)\left[P_{n+1}(x) P_n(x+h)-P_{n+1}(x+h) P_n(x)\right]\)

By expanding by Taylor’s there, we have

⇒ \(-h \sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x)\left\{P_r(x)+h P_r^{\prime}(x)+\cdots\right\}\)

⇒ \((n+1)\left[P_{n+1}(x)\left\{P_n(x)+h P_n^{\prime}(x)+\frac{h^2}{2!} P_n^{\prime \prime}(x)+\cdots\right\}\right.\)

⇒ \(\left.-\left\{P_{n+1}(x)+h P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)+\frac{h^2}{2!} P^{\prime \prime}{ }_{n+1}(x)+\cdots\right\} P_n^{\prime}(x)\right]\)

⇒ \(-h(n+1)\left[\left\{P_n(x) P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_n^{\prime}(x) P_{n+1}(x)+h(\ldots)+\cdots\right]\right.\)

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x)\left\{P_r(x)+h P_r^{\prime}(x)+\cdots\right\}\)

⇒ \((n+1)\left[P_n(x) P_{n+1}^{\prime \prime}(x)-P_n^{\prime}(x) P_{n+1}(x)+h(\ldots)+\cdots\right]\)

Taking the limit as h → 0, we have

⇒ \(\sum_{r=0}^n(2 r+1) P_r^2(x)=(n+1)\left[P_n(x) P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_n^{\prime}(x) P_{n+1}(x)\right]\)

⇒ \(P_0^2(x)+3 P_2^2+5 P_2^2(x)+\cdots+(2 n+1) P_n^2(x)\)

⇒ \((n+1)\left[P_n(x) P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_{n+1}(x) P_n^{\prime}(x)\right]\)

Again \((n+1)^2 P_n^2(x)+\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime 2}(x)\)

⇒ \((n+1) P_n(x)\left[(n+1) P_n(x)\right]+P_n^{\prime}(x)\left[\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}(x)\right]\)

⇒ \((n+1) P_n(x)\left[P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-x P_n^{\prime}(x)\right]+P_n^{\prime}(x)\left[(n+1)\left\{x P_n(x)-P_{n+1}(x)\right\}\right]\)

from recurrence formulas 4 and 6

⇒ \((n+1)\left[P_n(x) P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_{n+1}(x) P_n^{\prime}(x)\right]\)

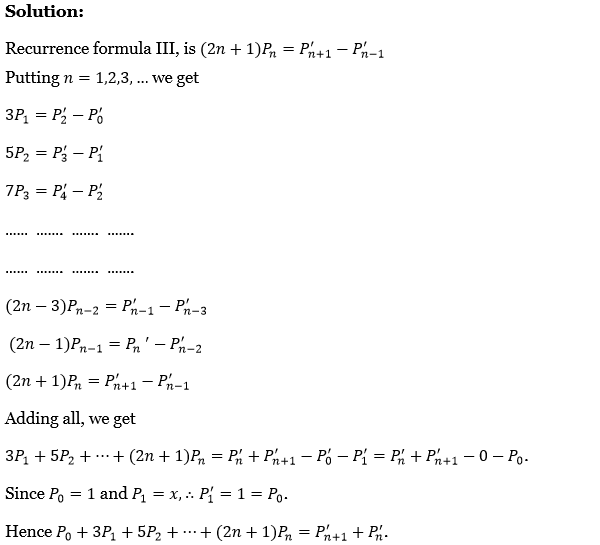

32. Prove that \(P_{n+1}^{\prime}+P_n^{\prime}=P_0+3 P_1+5 P_2+\ldots+(2 n+1) P_n=\sum_{r=1}^n(2 r+1) P_r(x)\).

Solution:

Recurrence formula 3, is \((2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

Putting n = 1,2,3,…. we get

⇒ \(3 P_1=P_2^{\prime}-P_0^{\prime}\)

⇒ \(5 P_2=P_3^{\prime}-P_1^{\prime}\)

⇒ \(7 P_3=P_4^{\prime}-P_2^{\prime}\)

…….. …….. ……. …….

…….. …….. ……. …….

⇒ \((2 n-3) P_{n-2}=P_{n-1}^{\prime}-P_{n-3}^{\prime}\)

⇒ \((2 n-1) P_{n-1}=P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-2}^{\prime}\)

⇒ \((2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}\)

Adding all we get

⇒ \(3 P_1+5 P_2+\cdots+(2 n+1) P_n=P_n^{\prime}+P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_0^{\prime}-P_1^{\prime}=P_n^{\prime}+P_{n+1}^{\prime}-0-P_0 .\)

Since \(P_0=1 \text { and } P_1=x, \)

∴ \(P_1^{\prime}=1=P_0\)

Hence \(P_0+3 P_1+5 P_2+\cdots+(2 n+1) P_n=P_{n+1}^{\prime}+P_n^{\prime}\)

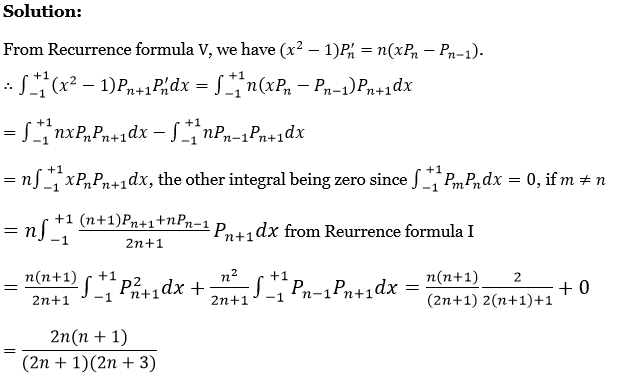

33. Prove that \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(x^2-1\right) P_{n+1} P_n^{\prime} d x=\frac{2 n(n+1)}{(2 n+1)(2 n+3)}\).

Solution:

From Recurrence formula V, we have \(\left(x^2-1\right) P_n^{\prime}=n\left(x P_n-P_{n-1}\right)\)

∴ \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(x^2-1\right) P_{n+1} P_n^{\prime} d x=\int_{-1}^{+1} n\left(x P_n-P_{n-1}\right) P_{n+1} d x\)

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^{+1} n x P_n P_{n+1} d x-\int_{-1}^{+1} n P_{n-1} P_{n+1} d x\)

⇒ \(n \int_{-1}^{+1} x P_n P_{n+1} d x\), the other integral being zero since \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_m P_n d x=0 \text {, if } m \neq n\)

⇒ \(n \int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}}{2 n+1} P_{n+1} d x\) from Recurrence formula 1

⇒ \(\frac{n(n+1)}{2 n+1} \int_{-1}^{+1} P_{n+1}^2 d x+\frac{n^2}{2 n+1} \int_{-1}^{+1} P_{n-1} P_{n+1} d x=\frac{n(n+1)}{(2 n+1)} \frac{2}{2(n+1)+1}+0\)

⇒ \(\frac{2 n(n+1)}{(2 n+1)(2 n+3)}\)

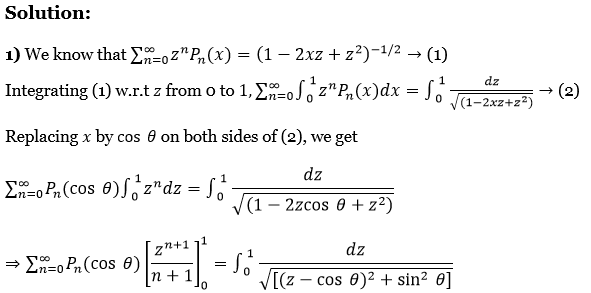

34. Proved that 1) \(1+\frac{1}{2} P_1(\cos \theta)+\frac{1}{3} P_2(\cos \theta)+\ldots=\log \left[\frac{1+\sin (\theta / 2)}{\sin (\theta / 2)}\right]\)

2) \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{P_n(\cos \theta)}{n+1}=\log \{1+\ cosec(\theta / 2)\}\)

Solution:

We know that \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} z^n P_n(x)=\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)^{-1 / 2} \rightarrow(1)\)

Integrating (1) w.r.t. z from 0 to 1, \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \int_0^1 z^n P_n(x) d x=\int_0^1 \frac{d z}{\sqrt{\left(1-2 x z+z^2\right)}} \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)

Replacing x by cos θ on both sides of (2), we get

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} P_n(\cos \theta) \int_0^1 z^n d z=\int_0^1 \frac{d z}{\sqrt{\left(1-2 z \cos \theta+z^2\right)}}\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} P_n(\cos \theta)\left[\frac{z^{n+1}}{n+1}\right]_0^1=\int_0^1 \frac{d z}{\sqrt{\left[(z-\cos \theta)^2+\sin ^2 \theta\right]}}\)

⇒ \(\left.\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{P_n(\cos \theta)}{n+1}=\left[\log \left\{(z-\cos \theta)+\sqrt{\left[(z-\cos \theta)^2+\sin ^2 \theta\right.}\right]\right\}\right]\)

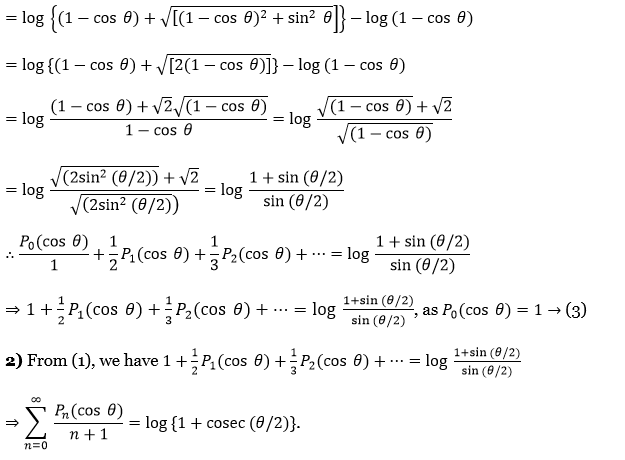

⇒ \(\left.=\log \left\{(1-\cos \theta)+\sqrt{\left[(1-\cos \theta)^2+\sin ^2 \theta\right.}\right]\right\}-\log (1-\cos \theta)\)

⇒ \(\log \left\{(1-\cos \theta)+\sqrt{\left[(1-\cos \theta)^2+\sin ^2 \theta\right]}\right\}-\log (1-\cos \theta)\)

⇒ \(\log \{(1-\cos \theta)+\sqrt{[2(1-\cos \theta)]}\}-\log (1-\cos \theta)\)

⇒ \(\log \frac{(1-\cos \theta)+\sqrt{2} \sqrt{(1-\cos \theta)}}{1-\cos \theta}=\log \frac{\sqrt{(1-\cos \theta)}+\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{(1-\cos \theta)}}\)

⇒ \(\log \frac{\sqrt{\left(2 \sin ^2(\theta / 2)\right)}+\sqrt{2}}{\left.\sqrt{\left(2 \sin ^2(\theta / 2)\right.}\right)}=\log \frac{1+\sin (\theta / 2)}{\sin (\theta / 2)}\)

∴\(\frac{P_0(\cos \theta)}{1}+\frac{1}{2} P_1(\cos \theta)+\frac{1}{3} P_2(\cos \theta)+\cdots=\log \frac{1+\sin (\theta / 2)}{\sin (\theta / 2)}\)

⇒ \(1+\frac{1}{2} P_1(\cos \theta)+\frac{1}{3} P_2(\cos \theta)+\cdots=\log \frac{1+\sin (\theta / 2)}{\sin (\theta / 2)} \text {, as } P_0(\cos \theta)=1 \rightarrow(3)\)

2. From (1), we have \(1+\frac{1}{2} P_1(\cos \theta)+\frac{1}{3} P_2(\cos \theta)+\cdots=\log \frac{1+\sin (\theta / 2)}{\sin (\theta / 2)}\)

⇒ \(\sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{P_n(\cos \theta)}{n+1}=\log \{1+{cosec}(\theta / 2)\}\)

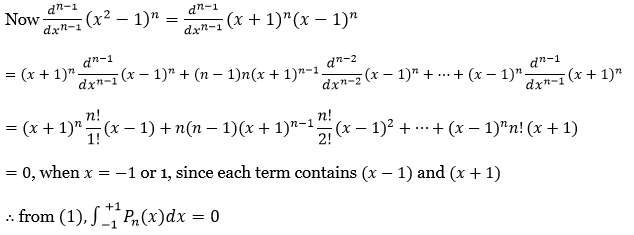

35. Prove that 1) \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_n(x) d x=0, n \neq 0 \text { and }\) 2) \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_0(x) d x=2\).

Solution:

From Rodrigue’s formula, we have \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{2^n n !} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\)

∴ \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_n(x) d x=\frac{1}{2^n n !} \int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x=\frac{1}{2^n n !}\left\{\frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right\}_{-1}^{+1} \rightarrow (1)\)

Now \(\frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n=\frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}(x+1)^n(x-1)^n\)

⇒ \((x+1)^n \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}(x-1)^n+(n-1) n(x+1)^{n-1} \frac{d^{n-2}}{d x^{n-2}}(x-1)^n+\cdots+(x-1)^n \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}(x+1)^n\)

⇒ \((x+1)^n \frac{n!}{1!}(x-1)+n(n-1)(x+1)^{n-1} \frac{n!}{2!}(x-1)^2+\cdots+(x-1)^n n!(x+1)\)

= 0, where x = -1 or 1, since each term contains (x-1) and (x+1)

∴ from (1), \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_n(x) d x=0\)

2) We know that \(P_0(x)=1\).

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_0(x) d x=\int_{-1}^{+1} d x=\{x\}_{-1}^{+1}=2\)

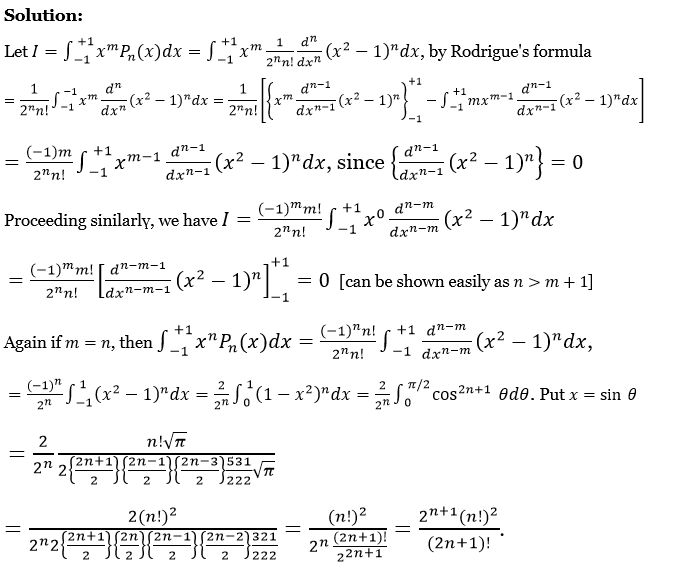

36. Prove that if m is an integer less than n, then

\(\int_{-1}^{+1} x^m P_n(x) d x=0 \text { and } \int_{-1}^{+1} x^n P_n(x) d x=\frac{2^{n+1}(n !)^2}{(2 n+1) !}\)

Solution:

Let l = \(\int_{-1}^{+1} x^m P_n(x) d x=\int_{-1}^{+1} x^m \frac{1}{2^n n!} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\), by Rodrigue’s formula

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2^n n!} \int_{-1}^{-1} x^m \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x=\frac{1}{2^n n!}\left[\left\{x^m \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right\}_{-1}^{+1}-\int_{-1}^{+1} m x^{m-1} \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1) m}{2^n n!} \int_{-1}^{+1} x^{m-1} \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x \text {, since }\left\{\frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right\}=0\)

Proceeding similarly, we have l = \(\frac{(-1)^m m!}{2^n n!} \int_{-1}^{+1} x^0 \frac{d^{n-m}}{d x^{n-m}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^m m!}{2^n n!}\left[\frac{d^{n-m-1}}{d x^{n-m-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right]_{-1}^{+1}=0\) [can be shown easily as n>m+1]

Again if m = n, then \(\int_{-1}^{+1} x^n P_n(x) d x=\frac{(-1)^n n!}{2^n n!} \int_{-1}^{+1} \frac{d^{n-m}}{d x^{n-m}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x,\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^n}{2^n} \int_{-1}^1\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x=\frac{2}{2^n} \int_0^1\left(1-x^2\right)^n d x=\frac{2}{2^n} \int_0^{\pi / 2} \cos ^{2 n+1} \theta d \theta \text {. Put } x=\sin \theta\)

⇒ \(\frac{2}{2^n} \frac{n!\sqrt{\pi}}{2\left\{\frac{2 n+1}{2}\right\}\left\{\frac{2 n-1}{2}\right\}\left\{\frac{2 n-3}{2}\right\} \frac{531}{222} \sqrt{\pi}}\)

⇒ \(\frac{2(n!)^2}{2^n 2\left\{\frac{2 n+1}{2}\right\}\left\{\frac{2 n}{2}\right\}\left\{\frac{2 n-1}{2}\right\}\left\{\frac{2 n-2}{2}\right\} \frac{321}{222}}=\frac{(n!)^2}{2^n \frac{(2 n+1)!}{2^{2 n+1}}}=\frac{2^{n+1}(n!)^2}{(2 n+1)!}\)

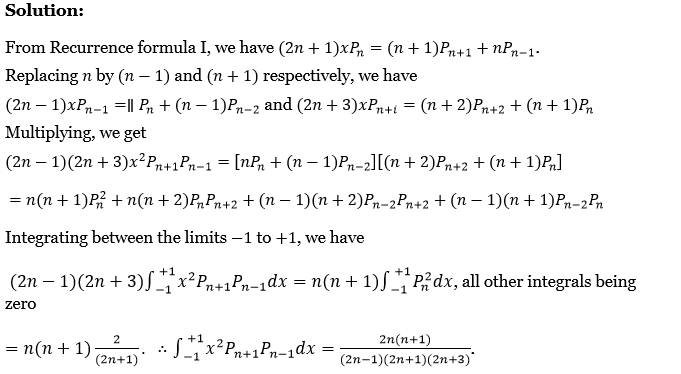

37. Prove that\(\int_{-1}^{+1} x^2 P_{n+1} P_{n-1} d x=\frac{2 n(n+1)}{(2 n-1)(2 n+1)(2 n+3)}\).

Solution:

From Recurrence formula 1, we have \((2 n+1) x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}\)

Replacing n by (n-1) and (n+1) respectively, we have

⇒ \((2 n-1) x P_{n-1}=\| P_n+(n-1) P_{n-2} \text { and }(2 n+3) x P_{n+i}=(n+2) P_{n+2}+(n+1) P_n\)

Multiplying, we get

⇒ \((2 n-1)(2 n+3) x^2 P_{n+1} P_{n-1}=\left[n P_n+(n-1) P_{n-2}\right]\left[(n+2) P_{n+2}+(n+1) P_n\right]\)

⇒ \(n(n+1) P_n^2+n(n+2) P_n P_{n+2}+(n-1)(n+2) P_{n-2} P_{n+2}+(n-1)(n+1) P_{n-2} P_n\)

Integrating between the limits -1 to +1, we have

⇒ \((2 n-1)(2 n+3) \int_{-1}^{+1} x^2 P_{n+1} P_{n-1} d x=n(n+1) \int_{-1}^{+1} P_n^2 d x\) all other integrals being zero

⇒ \(n(n+1) \frac{2}{(2 n+1)}\)

∴ \(\int_{-1}^{+1} x^2 P_{n+1} P_{n-1} d x=\frac{2 n(n+1)}{(2 n-1)(2 n+1)(2 n+3)}\)

38. Show that \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n(x) P_{n-1}(x) d x=\frac{2 n}{4 n^2-1}\).

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n(x) P_{n-1}(x) d x=\int_{-1}^1\left[\frac{n+1}{2 n+1} P_{n+1}^{-1}(x)+\frac{n}{2 n+1} P_{n-1}(x)\right] P_{n-1}(x) d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{n+1}{2 n+1} \int_{-1}^1 P_{n+1}(x) P_{n-1}(x) d x+\frac{n}{2 n+1} \int_{-1}^1\left[P_{n-1}(x)\right]^2 d x\)

⇒ \(0+\frac{n}{2 n+1} \times \frac{2}{2(n-1)+1}=\frac{2 n}{(2 n+1)(2 n-1)}=\frac{2 n}{4 n^2-1}\)

39. Prove that \(\int_{-1}^{+1} P_m(x) P_n(x) d x=\frac{2}{2 n+1}, \delta_{m n}\) where \(\delta_{m n}\) is the kronecker delta.

Solution:

We have \(\int_{-1}^1 P_m(x) P_n(x) d x=0\) if m≠n and \(\int_{-1}^1 P_m(x) P_n(x)=\frac{2}{2 n+1}\) if m=n

∴\(\int_{-1}^1 P_m^ (x) P_n(x) d x=\frac{2}{2 n+1} \delta_{m n}\) where \(\delta_{m n}\)) is the kroneker delta.

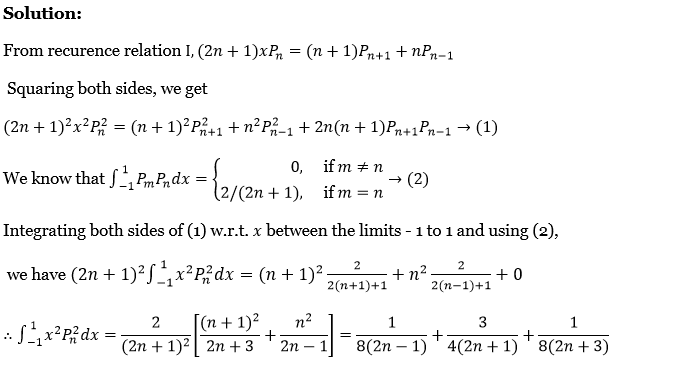

40. Prove that \(\int_{-1}^1 x^2 P_n^2 d x=\frac{1}{8(2 n-1)}+\frac{3}{4(2 n+1)}+\frac{1}{8(2 n+3)}\)

Solution:

from recurrence relation 1, \((2 n+1) x P_n=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}\)

Squaring both sides, we get

⇒ \((2 n+1)^2 x^2 P_n^2=(n+1)^2 P_{n+1}^2+n^2 P_{n-1}^2+2 n(n+1) P_{n+1} P_{n-1} \rightarrow \text { (1) }\)

We know that \(\int_{-1}^1 P_m P_n d x=\left\{\begin{aligned}

0, & \text { if } m \neq n \\

2 /(2 n+1), & \text { if } m=n

\end{aligned} \rightarrow\right. \text { (2) }\)

Integrating both sides of (1) w.r.t. x between the limits -1 to 1 and using (2),

we have \((2 n+1)^2 \int_{-1}^1 x^2 P_n^2 d x=(n+1)^2 \frac{2}{2(n+1)+1}+n^2 \frac{2}{2(n-1)+1}+0\)

∴ \(\int_{-1}^1 x^2 P_n^2 d x=\frac{2}{(2 n+1)^2}\left[\frac{(n+1)^2}{2 n+3}+\frac{n^2}{2 n-1}\right]=\frac{1}{8(2 n-1)}+\frac{3}{4(2 n+1)}+\frac{1}{8(2 n+3)}\)

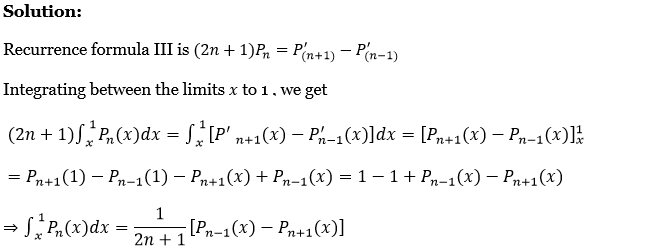

41. Prove that \(\int_x^1 P_n(x) d x=\frac{1}{2 n+1}\left[P_{n-1}(x)-P_{n+1}(x)\right]\)

Recurrence formula 3 is \((2 n+1) P_n=P_{(n+1)}^{\prime}-P_{(n-1)}^{\prime}\)

Integrating between the limits x to 1, we get

⇒ \((2 n+1) \int_x^1 P_n(x) d x=\int_x^1\left[P^{\prime}{ }_{n+1}(x)-P_{n-1}^{\prime}(x)\right] d x=\left[P_{n+1}(x)-P_{n-1}(x)\right]_x^1\)

⇒ \(P_{n+1}(1)-P_{n-1}(1)-P_{n+1}(x)+P_{n-1}(x)=1-1+P_{n-1}(x)-P_{n+1}(x)\)

⇒ \(\int_x^1 P_n(x) d x=\frac{1}{2 n+1}\left[P_{n-1}(x)-P_{n+1}(x)\right]\)

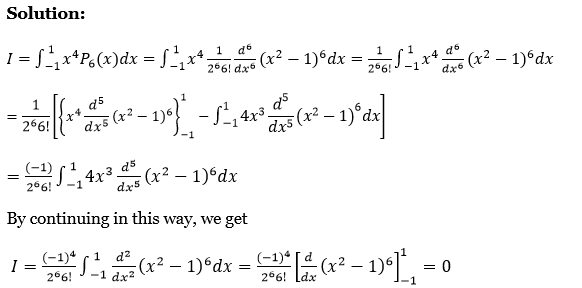

42. Show that \(\int_{-1}^{+1} x^4 P_6(x) d x=0\).

Solution:

⇒ \(I=\int_{-1}^1 x^4 P_6(x) d x=\int_{-1}^1 x^4 \frac{1}{2^6 6!} \frac{d^6}{d x^6}\left(x^2-1\right)^6 d x=\frac{1}{2^6 6!} \int_{-1}^1 x^4 \frac{d^6}{d x^6}\left(x^2-1\right)^6 d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2^6 6!}\left[\left\{x^4 \frac{d^5}{d x^5}\left(x^2-1\right)^6\right\}_{-1}^1-\int_{-1}^1 4 x^3 \frac{d^5}{d x^5}\left(x^2-1\right)^6 d x\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)}{2^6 6!} \int_{-1}^1 4 x^3 \frac{d^5}{d x^5}\left(x^2-1\right)^6 d x\)

By continuing in this way, we get

⇒ \(I=\frac{(-1)^4}{2^6 6!} \int_{-1}^1 \frac{d^2}{d x^2}\left(x^2-1\right)^6 d x=\frac{(-1)^4}{2^6 6!}\left[\frac{d}{d x}\left(x^2-1\right)^6\right]_{-1}^1=0\)

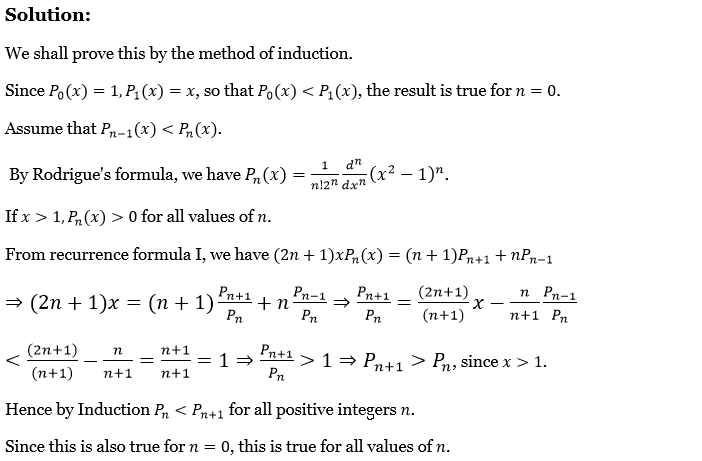

43. If x>1, show that \(P_n(x)<P_{n+1}(x)\).

Solution:

We shall prove this by the method of induction.

since \(P_0(x)=1, P_1(x)=x \text {, so that } P_0(x)<P_1(x)\), the result is true for n = 0

Assume that \(P_{n-1}(x)<P_n(x)\)

By Rodrigue’s formula, we have \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{n!2^n} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\)

If \(x>1, P_n(x)>0\) for all values of n.

From recurrence formula 1, we have \((2 n+1) x P_n(x)=(n+1) P_{n+1}+n P_{n-1}\)

⇒ \((2 n+1) x=(n+1) \frac{P_{n+1}}{P_n}+n \frac{P_{n-1}}{P_n} \Rightarrow \frac{P_{n+1}}{P_n}=\frac{(2 n+1)}{(n+1)} x-\frac{n}{n+1} \frac{P_{n-1}}{P_n}\)

⇒ \(<\frac{(2 n+1)}{(n+1)}-\frac{n}{n+1}=\frac{n+1}{n+1}=1 \Rightarrow \frac{P_{n+1}}{P_n}>1 \Rightarrow P_{n+1}>P_n \text {, since } x>1 \text {. }\)

Hence by Induction \(P_n<P_{n+1}\) for all positive integers n.

Since this is also true for n = 0, this is true for all values of n.

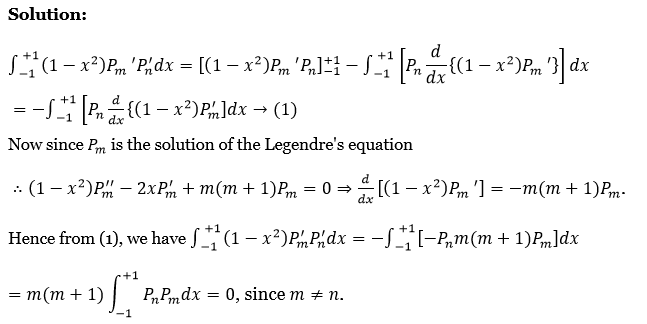

44. Prove that \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime} P_n^{\prime} d x=0\) where m and n are distinct positive integers.

Solution:

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime} P_n^{\prime} d x=\left[\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime} P_n\right]_{-1}^{+1}-\int_{-1}^{+1}\left[P_n \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime}\right\}\right] d x\)

\(-\int_{-1}^{+1}\left[P_n \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime}\right] d x \rightarrow\right. \text { (1) }\)Now since Pm is the solution of Legendre’s equation

∴ \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime \prime}-2 x P_m^{\prime}+m(m+1) P_m=0 \Rightarrow \frac{d}{d x}\left[\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime}\right]=-m(m+1) P_m\)

Hence from (1), we have \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(1-x^2\right) P_m^{\prime} P_n^{\prime} d x=-\int_{-1}^{+1}\left[-P_n m(m+1) P_m\right] d x\)

⇒ \(m(m+1) \int_{-1}^{+1} P_n P_m d x=0, \text { since } m \neq n\)

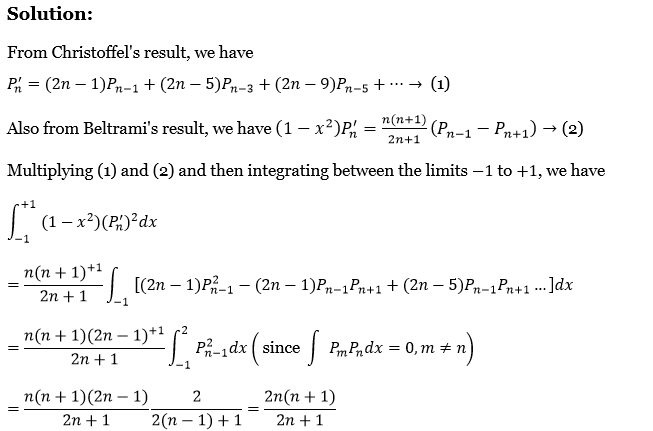

45. Prove that \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(1-x^2\right)\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2 d x=\frac{2 n(n+1)}{2 n+1}\).

Solution:

From Christoffel’s result, we have

⇒ \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+(2 n-9) P_{n-5}+\cdots \rightarrow \text { (1) }\)

Also from Beltramil’s result, we have \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime}=\frac{n(n+1)}{2 n+1}\left(P_{n-1}-P_{n+1}\right) \rightarrow(2)\)

Multiplying (1) and (2) and then integrating between the limits -1 to +1, we have

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(1-x^2\right)\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2 d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{n(n+1)^{+1}}{2 n+1} \int_{-1}\left[(2 n-1) P_{n-1}^2-(2 n-1) P_{n-1} P_{n+1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-1} P_{n+1} \ldots\right] d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{n(n+1)(2 n-1)^{+1}}{2 n+1} \int_{-1}^2 P_{n-1}^2 d x\left(\text { since } \int P_m P_n d x=0, m \neq n\right)\)

⇒ \(\frac{n(n+1)(2 n-1)}{2 n+1} \frac{2}{2(n-1)+1}=\frac{2 n(n+1)}{2 n+1}\)

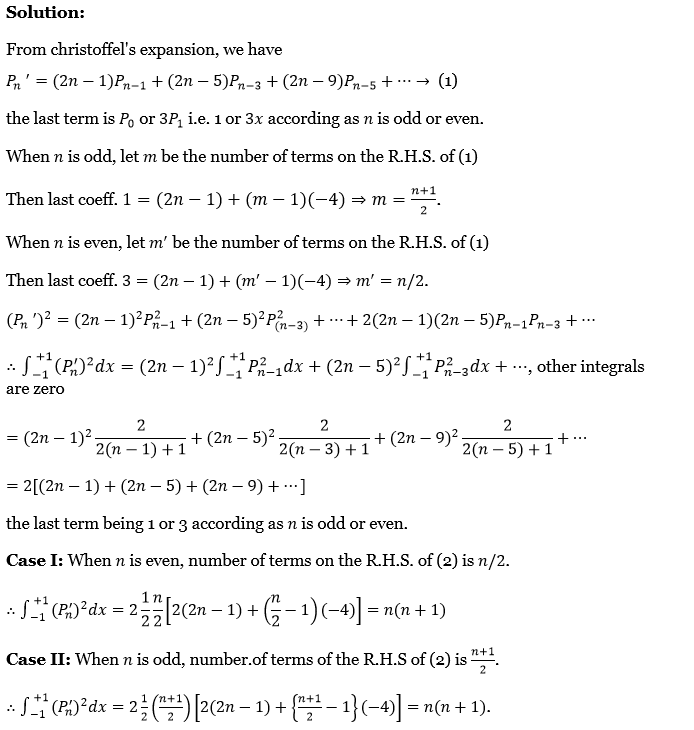

46. Prove that \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2 d x=n(n+1)\)

Solution:

From Christoffel’s expression, we have,

⇒ \(P_n^{\prime}=(2 n-1) P_{n-1}+(2 n-5) P_{n-3}+(2 n-9) P_{n-5}+\cdots \rightarrow \text { (1) }\)

The last term is P0 or 3P1 i.e., 1 or 3x according as n is odd or even.

When we n is odd, let m’ be the number of terms on R.H.S. of (1)

Then las coeff. 3 = \((2 n-1)+\left(m^{\prime}-1\right)(-4) \Rightarrow m^{\prime}=n / 2\)

⇒ \(\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2=(2 n-1)^2 P_{n-1}^2+(2 n-5)^2 P_{(n-3)}^2+\cdots+2(2 n-1)(2 n-5) P_{n-1} P_{n-3}+\cdots\)

∴ \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2 d x=(2 n-1)^2 \int_{-1}^{+1} P_{n-1}^2 d x+(2 n-5)^2 \int_{-1}^{+1} P_{n-3}^2 d x+\cdots,\) other integrals are zero

⇒ \((2 n-1)^2 \frac{2}{2(n-1)+1}+(2 n-5)^2 \frac{2}{2(n-3)+1}+(2 n-9)^2 \frac{2}{2(n-5)+1}+\cdots\)

⇒ \(2[(2 n-1)+(2 n-5)+(2 n-9)+\cdots]\)

the last term being 1 or 3 according as n is odd or even

Case 1: When n is even, the number of terms on the R.H.S. of (2) is n/2

∴ \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2 d x=2 \frac{1}{2} \frac{n}{2}\left[2(2 n-1)+\left(\frac{n}{2}-1\right)(-4)\right]=n(n+1)\)

Case 2: When n is odd, the number of terms of the R.H.S of (2) is \(\frac{n+1}{2}\)

∴ \(\int_{-1}^{+1}\left(P_n^{\prime}\right)^2 d x=2 \frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{n+1}{2}\right)\left[2(2 n-1)+\left\{\frac{n+1}{2}-1\right\}(-4)\right]=n(n+1)\)

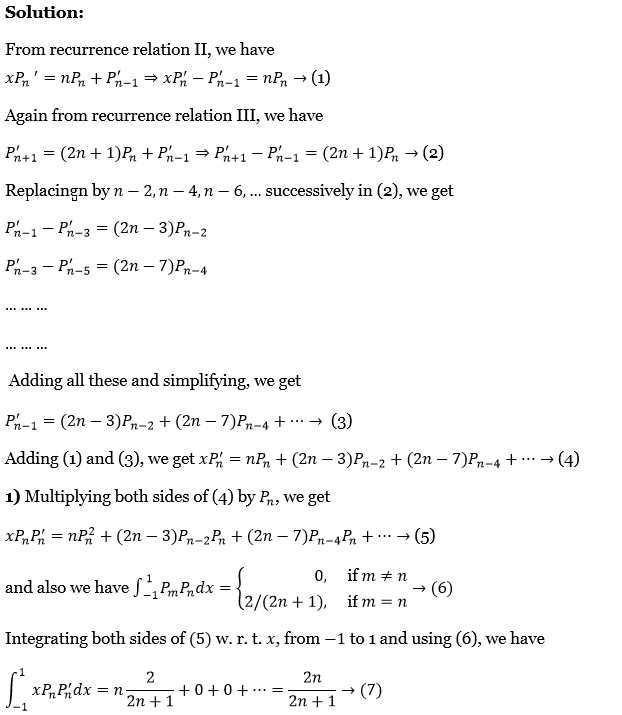

47. Prove that \(x P_n^{\prime}=n P_n+(2 n-3) P_{n-2}+(2 n-7) P_{n-4}+\ldots\) and hence or otherwise show that

1) \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_n^{\prime} d x=\frac{(2 n)}{(2 n+1)}\)

2) \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_m^{\prime} d x=\text { either } 0 \text { or } 2 \text { or } \frac{(2 n)}{(2 n+1)}\)

Solution:

1. From recurrence relation 3, we have

⇒ \(x P_n^{\prime}=n P_n+P_{n-1}^{\prime} \Rightarrow x P_n^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}=n P_n \rightarrow(1)\)

Again from recurrence relation 3, we have

⇒ \(P_{n+1}^{\prime}=(2 n+1) P_n+P_{n-1}^{\prime} \Rightarrow P_{n+1}^{\prime}-P_{n-1}^{\prime}=(2 n+1) P_n \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)

Replacing by n-2, n-4,n-6, …….. successive in (20, we get

⇒ \(P_{n-1}^{\prime}-P_{n-3}^{\prime}=(2 n-3) P_{n-2}\)

⇒ \(P_{n-3}^{\prime}-P_{n-5}^{\prime}=(2 n-7) P_{n-4}\)

…….. ………. …………

…….. ………. ……….

Adding all these and simplifying, we get

Multiplying both sides of (4) by Pn, we get

⇒ \(x P_n P_n^{\prime}=n P_n^2+(2 n-3) P_{n-2} P_n+(2 n-7) P_{n-4} P_n+\cdots \rightarrow(5)\)

and also we have \(\int_{-1}^1 P_m P_n d x=\left\{\begin{aligned}

0, & \text { if } m \neq n \\

2 /(2 n+1), & \text { if } m=n

\end{aligned} \rightarrow(6)\right.\)

Integrating both sides of (5) w.r.t. x, from -1 to 1and using (6) we have

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_n^{\prime} d x=n \frac{2}{2 n+1}+0+0+\cdots=\frac{2 n}{2 n+1} \rightarrow \text { (7) }\)

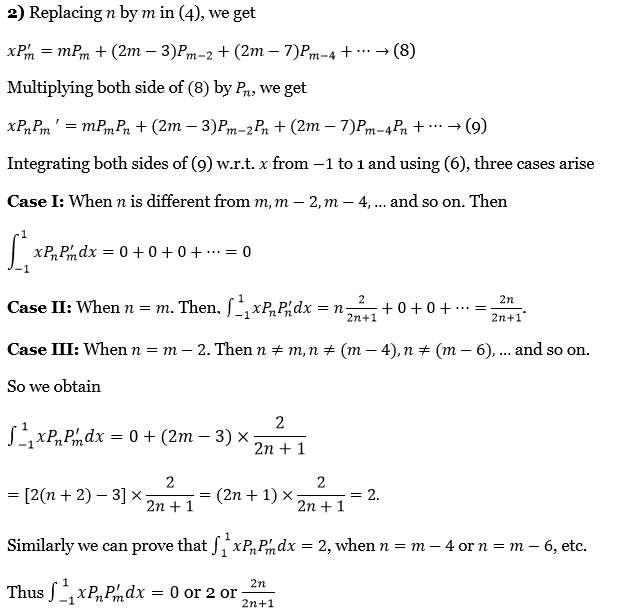

2. Replacing n by m in (4), we get \(\)

⇒ \(x P_m^{\prime}=m P_m+(2 m-3) P_{m-2}+(2 m-7) P_{m-4}+\cdots \rightarrow(8)\)

Multiplying both sides of (8) by Pn, we get

⇒ \(x P_n P_m{ }^{\prime}=m P_m P_n+(2 m-3) P_{m-2} P_n+(2 m-7) P_{m-4} P_n+\cdots \rightarrow \text { (9) }\)

Integrating both sides of (9) w.r.t.x, from -1 to 1, and using (6), three cases arise

Case 1: When n is different from m,m-2, m-4, ….. and so on. Then

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_m^{\prime} d x=0+0+0+\cdots=0\)

Case 2: When n = m. Then \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_n^{\prime} d x=n \frac{2}{2 n+1}+0+0+\cdots=\frac{2 n}{2 n+1}\)

Case 3: When n = m .Then n ≠ m, n≠(m-4), n ≠ (m-6), ……… and so on.

So we obtain

⇒ \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_m^{\prime} d x=0+(2 m-3) \times \frac{2}{2 n+1}\)

⇒ \([2(n+2)-3] \times \frac{2}{2 n+1}=(2 n+1) \times \frac{2}{2 n+1}=2\)

Similarly we can prove that \(\int_1^1 x P_n P_m^{\prime} d x=2\), when n = 4 or n = m-6, etc.

Thus \(\int_{-1}^1 x P_n P_m^{\prime} d x=0 \text { or } 2 \text { or } \frac{2 n}{2 n+1}\)

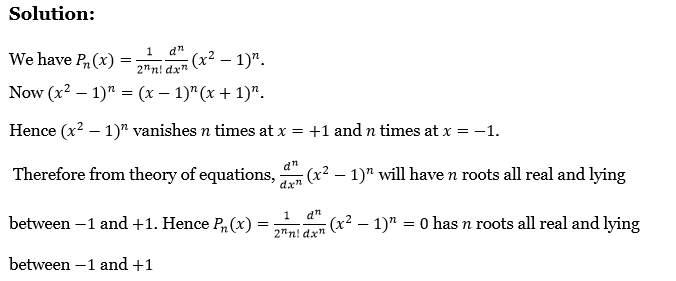

48. Show that all the roots of \(\) are real and lie between -1 and +1.

Solution:

We have \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{2^n n!} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\)

Now \(\left(x^2-1\right)^n=(x-1)^n(x+1)^n\)

Hence \(\left(x^2-1\right)^n\) vanishes n times at x = +1 and n times x = -1

Therefore from a theory of equations, \(\frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\) will have n roots all real and lying between -1 and +1

Hence \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{2^n n} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n=0\) has n roots all real and lying between -1 and +1

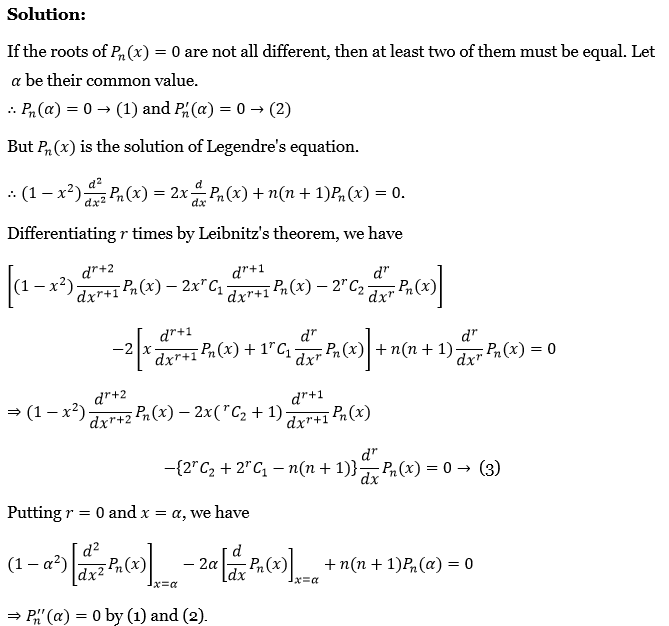

49. Prove that all the roots of \(\) are distinct.

Solution:

If the roots of Pn(x) = 0 are not different, then at least two of them must be equal.

Let α be their common value.

∴ \(P_n(\alpha)=0 \rightarrow(1) \text { and } P_n^{\prime}(\alpha)=0 \rightarrow \text { (2) }\)

But Pn(x) is the solution of Legendre’s equation.

∴ \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^2}{d x^2} P_n(x)=2 x \frac{d}{d x} P_n(x)+n(n+1) P_n(x)=0\)

Differentiating r times by Leibnitz’s theorem, we have

⇒ \(\left[\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^{r+2}}{d x^{r+1}} P_n(x)-2 x^r C_1 \frac{d^{r+1}}{d x^{r+1}} P_n(x)-2^r C_2 \frac{d^r}{d x^r} P_n(x)\right]\)

⇒ \(-2\left[x \frac{d^{r+1}}{d x^{r+1}} P_n(x)+1^r C_1 \frac{d^r}{d x^r} P_n(x)\right]+n(n+1) \frac{d^r}{d x^r} P_n(x)=0\)

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^{r+2}}{d x^{r+2}} P_n(x)-2 x\left({ }^r C_2+1\right) \frac{d^{r+1}}{d x^{r+1}} P_n(x)\)

⇒ \(-\left\{2^r C_2+2^r C_1-n(n+1)\right\} \frac{d^r}{d x} P_n(x)=0 \rightarrow(3)\)

Putting r = 0 and x = α, we have

⇒ \(\left(1-\alpha^2\right)\left[\frac{d^2}{d x^2} P_n(x)\right]_{x=\alpha}-2 \alpha\left[\frac{d}{d x} P_n(x)\right]_{x=\alpha}+n(n+1) P_n(\alpha)=0\)

Similarly, by writing r = 1,2,3, ………. in (3)and simplifying stepwise we have

⇒ \(P_n^{\prime \prime \prime}(\alpha)=0=P_n^{i v}(\alpha)=\cdots=P_n^n(\alpha)\)

But since \(P_n(x)=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \ldots(2 n-1)}{n!^0}\left[x^n-\frac{n(n-1)}{2(2 n-1)} x^{n-2} \cdots\right]\)

∴ \(P_n^n(\alpha)=\frac{1 \cdot 3 \cdots(2 n-1)}{n!} n!\)

Hence \(P_n^n(\alpha) \neq 0 \text {. }\)

Therefore our assumption that \(P_n(x)=0\) is distinct.

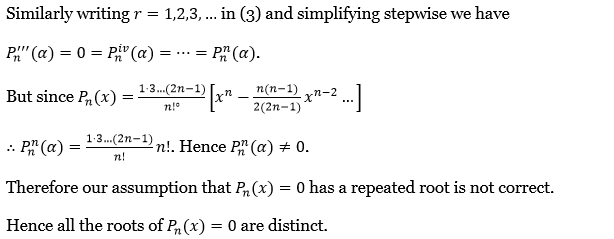

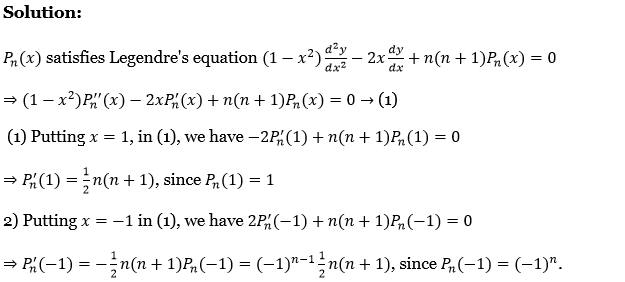

50. Prove that 1) \(P_n^{\prime}(1)=\frac{1}{2} n(n+1)\) 2) \(P_n^{\prime}(-1)=(-1)^{n-1} \frac{1}{2} n(n+1)\)

Solution:

Pn(x) satisfies Legendre’s equation \(\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d^2 y}{d x^2}-2 x \frac{d y}{d x}+n(n+1) P_n(x)=0\)

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) P_n^{\prime \prime}(x)-2 x P_n^{\prime}(x)+n(n+1) P_n(x)=0 \rightarrow(1)\)

(1) Putting x = 1, in (1), we have \(-2 P_n^{\prime}(1)+n(n+1) P_n(1)=0\)

⇒ \(P_n^{\prime}(1)=\frac{1}{2} n(n+1), \text { since } P_n(1)=1\)

(2) Putting x = -1 in (1), we have \(2 P_n^{\prime}(-1)+n(n+1) P_n(-1)=0\)

⇒ \(P_n^{\prime}(-1)=-\frac{1}{2} n(n+1) P_n(-1)=(-1)^{n-1} \frac{1}{2} n(n+1) \text {, since } P_n(-1)=(-1)^n\)

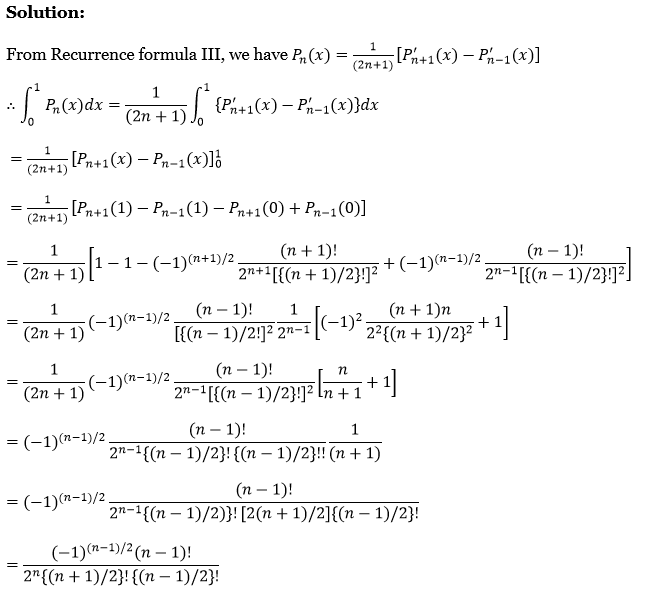

51. Prove that \(\int_0^1 P_n(x) d x=\frac{(-1)^{(n-1) / 2}(n-1) !}{2^n\{(n+1) / 2\} !\{(n-1) / 2\} !}\) when n is odd.

Solution:

From Recurrence formula 3, we have \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{(2 n+1)}\left[P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_{n-1}^{\prime}(x)\right]\)

∴ \(\int_0^1 P_n(x) d x=\frac{1}{(2 n+1)} \int_0^1\left\{P_{n+1}^{\prime}(x)-P_{n-1}^{\prime}(x)\right\} d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{(2 n+1)}\left[P_{n+1}(x)-P_{n-1}(x)\right]_0^1\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{(2 n+1)}\left[P_{n+1}(1)-P_{n-1}(1)-P_{n+1}(0)+P_{n-1}(0)\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{(2 n+1)}\left[1-1-(-1)^{(n+1) / 2} \frac{(n+1)!}{2^{n+1}[\{(n+1) / 2\}!]^2}+(-1)^{(n-1) / 2} \frac{(n-1)!}{2^{n-1}[\{(n-1) / 2\}!]^2}\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{(2 n+1)}(-1)^{(n-1) / 2} \frac{(n-1)!}{\left[\{(n-1) / 2!]^2\right.} \frac{1}{2^{n-1}}\left[(-1)^2 \frac{(n+1) n}{2^2\{(n+1) / 2\}^2}+1\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{(2 n+1)}(-1)^{(n-1) / 2} \frac{(n-1)!}{2^{n-1}[\{(n-1) / 2\}!]^2}\left[\frac{n}{n+1}+1\right]\)

⇒ \((-1)^{(n-1) / 2} \frac{(n-1)!}{2^{n-1}\{(n-1) / 2\}!\{(n-1) / 2\}!!} \frac{1}{(n+1)}\)

⇒ \((-1)^{(n-1) / 2} \frac{(n-1)!}{\left.2^{n-1}\{(n-1) / 2)\right\}![2(n+1) / 2]\{(n-1) / 2\}!}\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^{(n-1) / 2}(n-1)!}{2^n\{(n+1) / 2\}!\{(n-1) / 2\}!}\)

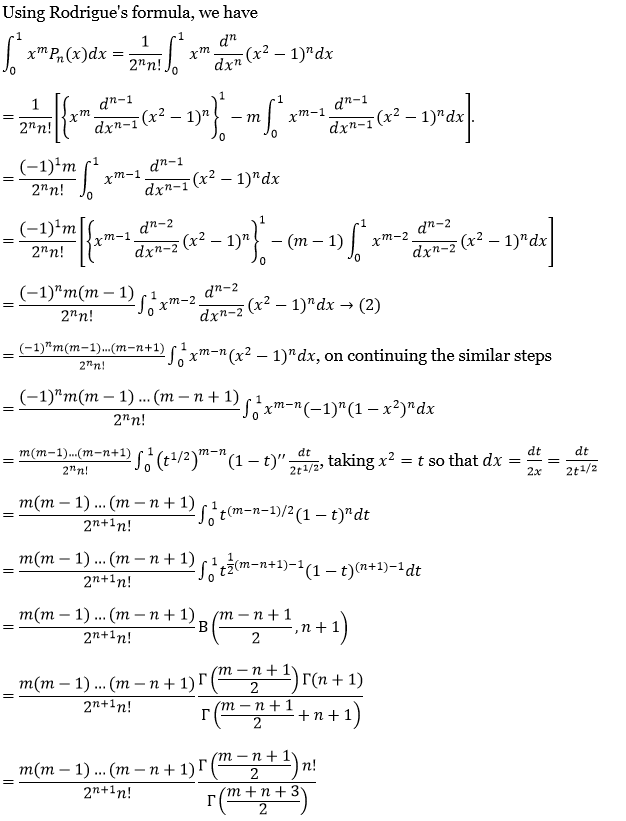

52. If m>n-1 and n is a positive integer, prove that

⇒ \(\int_0^1 x^m P_n(x) d x=\frac{m(m-1)(m-2) \ldots(m-n+2)}{(m+n+1)(m+n-1) \ldots(m-n+3)}\)

Solution:

Solution:

Using Rodrigue’s formula, we have

⇒ \(\int_0^1 x^m P_n(x) d x=\frac{1}{2^n n!} \int_0^1 x^m \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{1}{2^n n!}\left[\left\{x^m \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right\}_0^1-m \int_0^1 x^{m-1} \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^1 m}{2^n n!} \int_0^1 x^{m-1} \frac{d^{n-1}}{d x^{n-1}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^1 m}{2^n n!}\left[\left\{x^{m-1} \frac{d^{n-2}}{d x^{n-2}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right\}_0^1-(m-1) \int_0^1 x^{m-2} \frac{d^{n-2}}{d x^{n-2}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\right]\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^n m(m-1)}{2^n n!} \int_0^1 x^{m-2} \frac{d^{n-2}}{d x^{n-2}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x \rightarrow(2)\)

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^n m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^n n!} \int_0^1 x^{m-n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n d x\), on continuing the similar steps

⇒ \(\frac{(-1)^n m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^n n!} \int_0^1 x^{m-n}(-1)^n\left(1-x^2\right)^n d x\)

⇒ \(\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^n n!} \int_0^1\left(t^{1 / 2}\right)^{m-n}(1-t)^{\prime \prime} \frac{d t}{2 t^{1 / 2}}, \text { taking } x^2=t \text { so that } d x=\frac{d t}{2 x}=\frac{d t}{2 t^{1 / 2}}\)

⇒ \(\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^{n+1} n!} \int_0^1 t^{(m-n-1) / 2}(1-t)^n d t\)

⇒ \(\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^{n+1} n!} \int_0^1 t^{\frac{1}{2}(m-n+1)-1}(1-t)^{(n+1)-1} d t\)

⇒ \(\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^{n+1} n!} \mathrm{B}\left(\frac{m-n+1}{2}, n+1\right)\)

⇒ \(\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^{n+1} n!} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{m-n+1}{2}\right) \Gamma(n+1)}{\Gamma\left(\frac{m-n+1}{2}+n+1\right)}\)

⇒ \(=\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1) \Gamma\left(\frac{m-n+1}{2}\right)}{2^{n+1} \times \frac{m+n+1}{2} \cdot \frac{m+n-1}{2} \ldots \frac{m-n+1}{2} \Gamma\left(\frac{m-n+1}{2}\right)}\)

⇒ \(=\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{(m+n+1)(m+n-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}=\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+2)}{(m+n+1)(m+n-1) \ldots(m-n+3)}\)

⇒ \(\frac{m(m-1) \ldots(m-n+1)}{2^{n+1} n!} \frac{\Gamma\left(\frac{m-n+1}{2}\right) n!}{\Gamma\left(\frac{m+n+3}{2}\right)}\)

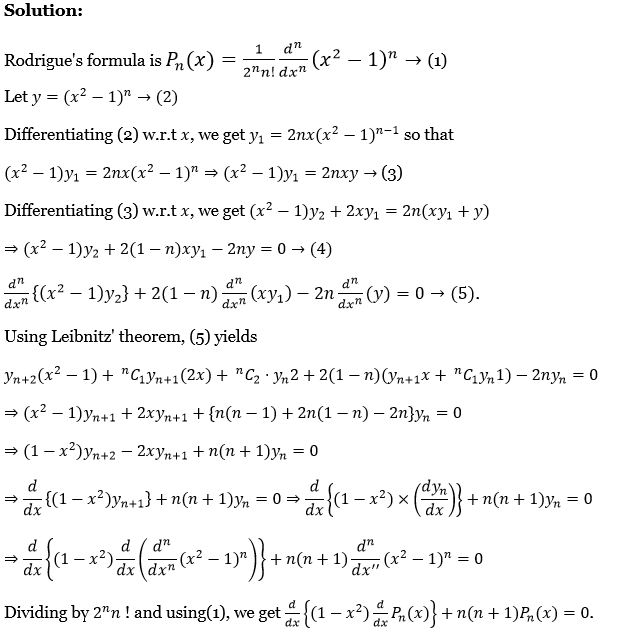

53. Using Rodrigue’s formula, show that \(\) satisfies

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d}{d x} P_n(x)\right\}+n(n+1) P_n(x)=0\).

Solution:

Rodrigue’s formula is \(P_n(x)=\frac{1}{2^n n!} \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n \rightarrow(1)\)

Le6t y = \(\left(x^2-1\right)^n \rightarrow(2)\)

Differentiating (2) w.r.t.x, we get \(y_1=2 n x\left(x^2-1\right)^{n-1}\) so that

⇒ \(\left(x^2-1\right) y_1=2 n x\left(x^2-1\right)^n \Rightarrow\left(x^2-1\right) y_1=2 n x y \rightarrow(3)\)

Differentiating (3) w.r.t.x, we get \(\left(x^2-1\right) y_2+2 x y_1=2 n\left(x y_1+y\right)\)

⇒ \(\left(x^2-1\right) y_2+2(1-n) x y_1-2 n y=0 \rightarrow(4)\)

⇒ \(\frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left\{\left(x^2-1\right) y_2\right\}+2(1-n) \frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x y_1\right)-2 n \frac{d^n}{d x^n}(y)=0 \rightarrow(5)\)

Using Leibnitz’s theorem, (5) yields

⇒ \(y_{n+2}\left(x^2-1\right)+{ }^n C_1 y_{n+1}(2 x)+{ }^n C_2 \cdot y_n 2+2(1-n)\left(y_{n+1} x+{ }^n C_1 y_n 1\right)-2 n y_n=0\)

⇒ \(\left(x^2-1\right) y_{n+1}+2 x y_{n+1}+\{n(n-1)+2 n(1-n)-2 n\} y_n=0\)

⇒ \(\left(1-x^2\right) y_{n+2}-2 x y_{n+1}+n(n+1) y_n=0\)

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) y_{n+1}\right\}+n(n+1) y_n=0 \Rightarrow \frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \times\left(\frac{d y_n}{d x}\right)\right\}+n(n+1) y_n=0\)

⇒ \(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d}{d x}\left(\frac{d^n}{d x^n}\left(x^2-1\right)^n\right)\right\}+n(n+1) \frac{d^n}{d x^{n \prime}}\left(x^2-1\right)^n=0\)

Dividing by 2nn! and using (1), we get \(\frac{d}{d x}\left\{\left(1-x^2\right) \frac{d}{d x} P_n(x)\right\}+n(n+1) P_n(x)=0\)