Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Linear Transformations and Matrices

Page 84 Problem 1 Answer

In the question given that V and W are finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and T, U: V→W are linear transformations.

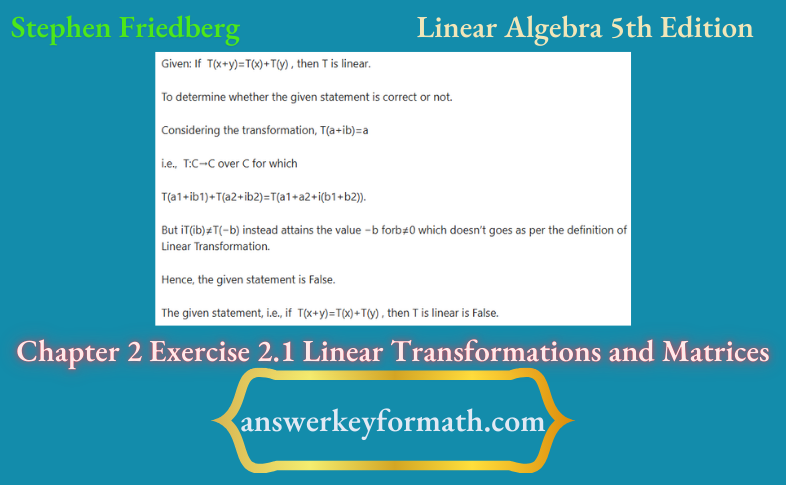

It is required to find that the statement is false or true.

With the help of the definition of the tip section, the statement, either true or false, can be obtained easily.

It is observed from the definition that for any scalar a, a∈F,aT+U is a linear transformation from V to W.

Hence, the statement is true.

The following statement is true.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 84 Problem 2 Answer

In the question given that V and W are finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and T, U: V→W are linear transformations.

Read and Learn More Stephen Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition Solutions

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 84 Problem 3 Answer

In the question given that V and W are finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and T, U: V→W are linear transformations.

It is required to find that the statement if m=dim(V) and n=dim(W), then [T]βγ is an m×n matrix is false or true.

With the help of the definition of the tip section, the statement, either true or false, can be obtained easily.

By observing the definition and the statement it is clear that statement if m=dim(V) and n=dim(W), then [T]βγ is an n×m matrix.

Hence, the given statement is false.

The following statement is false.

Stephen Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition Solutions For Exercise 2.2 Chapter 2 Page 84 Problem 4 Answer

Given: V and W are finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and T, U: V→W are linear transformations.

To find: Whether the statement [T+U]βγ=[T]βγ+[U]βγ is false or true.

With the help of the theorem of the tip section, the statement, either true or false, can be obtained easily.

It is clearly observed from the theorem that [T+U]βγ=[T]βγ+[U]βγ when V and W be finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and let T, U: V→W be linear transformations.

Hence, the statement is true.

The given statement is true.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 84 Problem 5 Answer

In the question given that V and W are finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and T, U: V→W are linear transformations.

It is required to find that the statement L(V, W) is a vector space is false or true.

With the help of the definition of the tip section, the statement, either true or false, can be obtained easily.

From the definition it is clearly observed that the vector space of all linear transformations from V into W denotes by L(V,W).

Hence, L(V, W) is a vector space. The statement is true.

The given statement is true.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 84 Problem 6 Answer

Given: V and W are finite-dimensional vector spaces with ordered bases β and γ, respectively, and T, U: V→W are linear transformations.

To find: Whether the statement L(V, W)=L(W, V) is false or true.

With the help of the definition of the tip section, the statement, either true or false, can be obtained easily.

From the definition it is clearly observed that the vector space of all linear transformations from V into W denotes by L(V,W) and it also can be written as L(V) instead of L(V,W).

Hence, L(V,W).

Therefore, the statement L(V,W)=L(W,V)is false.

The given statement is false.

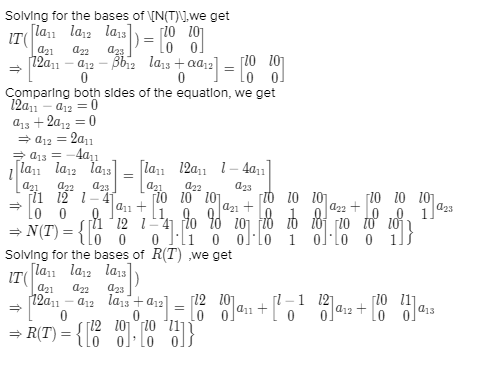

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 85 Problem 7 Answer

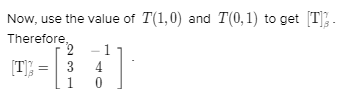

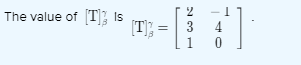

In the question given T:R2→R3 defined by T(a1,a2)=(2a1−a2,3a1+4a2,a1).

It is required to compute [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given, T:R2→R3 defined by T(a1,a2)=(2a1−a2,3a1+4a2,a1).

From the question β and γ be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm, respectively, for each linear transformation T: Rn→Rm.

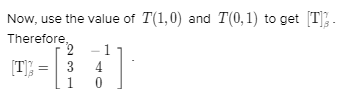

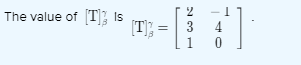

Hence,

⇒ β={(1,0),(0,1)}

⇒ γ={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0)=(2,3,1)

⇒T(1,0)=2⋅(1,0,0)+3⋅(0,1,0)+1⋅(0,0,1)

⇒ T(0,1)=(−1,4,0)

⇒T(0,1)=−1⋅(1,0,0)+4⋅(0,1,0)+0⋅(0,0,1)

Chapter 2 Exercise 2.2 Linear Transformations Solved Problems Page 85 Problem 8 Answer

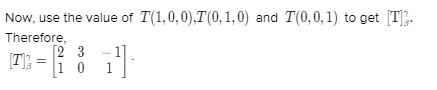

In the question given T:R3→R2 defined by T(a1,a2,a3)=(2a1+3a2−a3,a1+a3).It is required to compute [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given, T: R3→R2 defined by

⇒ T(a1,a2,a3)=(2a1+3a2−a3,a1+a3).

From the question β and γ be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm, respectively, for each linear transformation T: Rn→Rm.

Hence,

⇒ β={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

⇒ γ={(1,0),(0,1)}

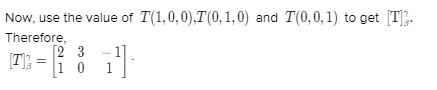

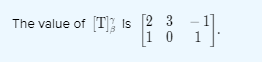

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0,0)=(2,1)=2⋅(1,0)+1⋅(0,1)

⇒ T(0,1,0)=(3,0)=3⋅(1,0)+0⋅(0,1)

⇒ T(0,0,1)=(−1,1)=−1⋅(1,0)+1⋅(0,1)

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 85 Problem 9 Answer

Given: T:R3→R defined by T(a1,a2,a3)=2a1+a2−3a3

To find: [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given, T: R3→R defined by

⇒ T(a1,a2,a3)=2a1+a2−3a3.

From the question β and be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm, respectively, for each linear transformation

⇒ T: Rn→Rm.

Hence,

⇒ β={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

⇒ γ={1}

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0,0)=2=2⋅1

⇒ T(0,1,0)=1=1⋅1

⇒ T(0.0.1)=−3=−3⋅1

Now, use the value of T(1,0,0),T(0,1,0) and T(0,0,1) to get [T]βγ.

Therefore,

⇒ [T]βγ=[21−3].

The value of [T]βγ is [T]βγ=[21−3].

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 85 Problem 10 Answer

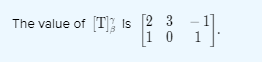

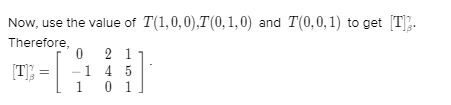

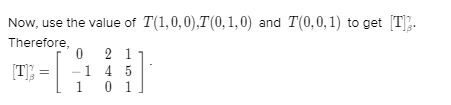

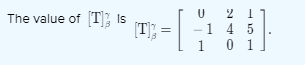

In the question given T: R3→R3 defined by T(a1,a2,a3)=(2a2+a3,−a1+4a2+5a3,a1+a3).

It is required to compute [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given, T:R3→R defined by T(a1,a2,a3)=2a1+a2−3a3.

From the question β and γ be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm, respectively, for each linear transformation

T: Rn→Rm.

Hence,

⇒ β={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

⇒ β=γ={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0,0)=(0,−1,1)=0⋅(1,0,0)−1⋅(0,1,0)+1⋅(0,0,1)

⇒ T(0,1,0)=(2,4,0)=2⋅(1,0,0)+4⋅(0,1,0)+0⋅(0,0,1)

⇒ T(0,0,1)=(1,5,1)=1⋅(1,0,0)+5⋅(0,1,0)+1⋅(0,0,1).

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 85 Problem 11 Answer

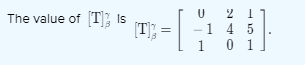

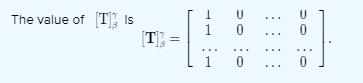

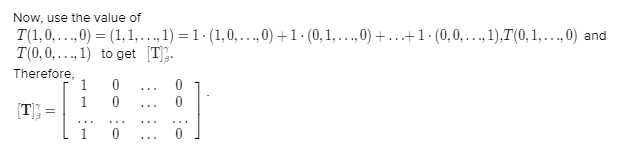

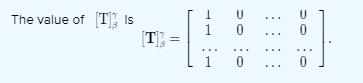

In the question given T:Rn→Rn defined by T(a1,a2,…,an)=(a1,a1,…,a1).

It is required to compute [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given, ,T:Rn→Rn defined by

⇒ T(a1,a2,…,an)=(a1,a1,…,a1)

From the question β and γ be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm respectively, for each linear transformation T: Rn→Rm.

Hence,

⇒ β={(1,0,…,0),(0,1,…,0),…,(0,0,…,1)}

⇒ γ={(1,0,…,0),(0,1,…,0),…,(0,0,…,1)}

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0,…,0)=(1,1,…,1)=1⋅(1,0,…,0)+1⋅(0,1,…,0)+…+1⋅(0,0,…,1)

⇒ T(0,1,…,0)=(0,0,…,0)=0⋅(1,0,…,0)+0⋅(0,1,…,0)+…+0⋅(0,0,…,1)

⇒ T(0,0,…,1)=(0,0,…,0)=0⋅(1,0,…,0)+0⋅(0,1,…,0)+…+0⋅(0,0,…,1).

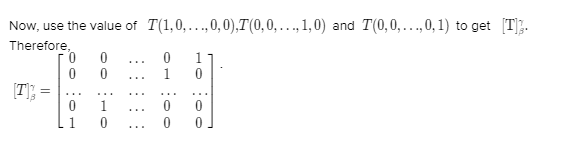

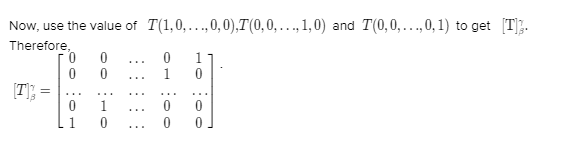

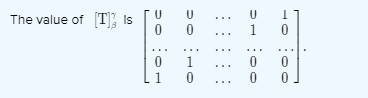

Linear Algebra Friedberg Exercise 2.2 Matrices Step-By-Step Guide Page 85 Problem 12 Answer

Given: T: Rn→Rn defined by

T(a1,a2,…,an)=(˙an,an−1,…,a1).

To fin: [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given, T:Rn→Rn defined by T(a1,a2,…,an)=(a1,a1,…,a1).

From the question β and γ be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm, respectively, for each linear transformation T: Rn→Rm.

Hence,

⇒ β={(1,0,…,0,0),(0,1,…,0,0),…,(0,0,…,1,0),(0,0,…,0,1)}

⇒ γ={(1,0,…,0,0),(0,1,…,0,0),…,(0,0,…,1,0),(0,0,…,0,1)}

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0,…,0,0)=(0,0,…,0,1)

=0⋅(1,0,…,0,0)+0⋅(0,1,…,0,0)+…+0⋅(0,0,…,1,0)+1⋅(0,0,…,0,1)

⇒ T(0,1,…,0,0)=(0,0,…,1,0)

=0⋅(1,0,…,0,0)+0⋅(0,1,…,0,0)+…+1⋅(0,0,…,1,0)+0⋅(0,0,…,0,1)..

⇒ T(0,0,…,1,0)=(0,1,…,0,0)

=0⋅(1,0,…,0,0)+1⋅(0,1,…,0,0)+…+0⋅(0,0,…,1,0)+0⋅(0,0,…,0,1)

⇒ T(0,0,…,0,1)=(1,0,…,0,0)

=1⋅(1,0,…,0,0)+0⋅(0,1,…,0,0)+…+0⋅(0,0,…,1,0)+0⋅(0,0,…,0,1)

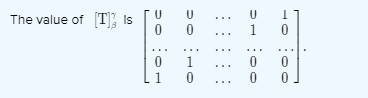

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 85 Problem 13 Answer

In the question given T: Rn→R defined by

⇒ T(a1,a2,…,an)=a1+an.

It is required to compute [T]βγ.

With the help of the definition of the matrix, the representation of a linear transformation [T]βγ can be computed easily.

Given ,T:Rn→Rn defined by T(a1,a2,…,an)=(a1,a1,…,a1).

From the question β and γ be the standard ordered bases for Rn and Rm respectively, for each linear transformation T: Rn→Rm.

Hence,β={(1,0,…,0,0),(0,1,…,0,0),…,(0,0,…,1,0),(0,0,…,0,1)}

⇒ γ={1}

Therefore,

⇒ T(1,0,…,0,0)=1=1⋅1

⇒ T(0,1,…,0,0)=0=0⋅1

⇒ T(0,0,…,1,0)=0=0⋅1

⇒ T(0,0,…,0,1)=1=1⋅1.

Now, use the value of T(1,0,…,0,0),T(0,0,…,1,0) and T(0,0,…,0,1) to get [T]βγ.

Therefore,

⇒ [T]βγ=35.

The value of [T]βγ is 35.

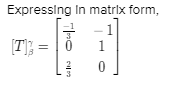

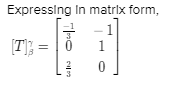

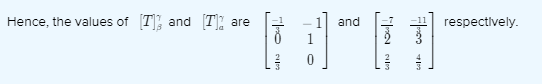

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 85 Problem 14 Answer

Given: T:R2→R3 is defined as: T(a1,a2)=(a1−a2,a1,2a1+a2).

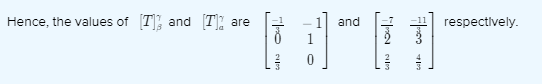

To find: The values of [T]βγ and [T]aγ.

Analyzing the question, the values of T(1,0) and T(0,1) can be determined.

Using the values of T(1,0) and T(0,1), the unknown value of [T]βγ can be found.

Evaluating T(α) and writing it as a linear combination of the elements of γ, the unknown value of [T]aγ can be determined.

According to the question,

T(a1,a2)=(a1−a2,a1,2a1+a2)

Substituting the value of a1 by 1 and a2 by 0,

⇒ T(1,0)=(1−0,1,2(1)+0)

=(1,1,2)

=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3)

Expressing in linear system of equations,

⇒ A+2C=1

⇒ A+B+2C=1

⇒ B+3C=2

Solving the linear system of equations,

⇒ A=−1/3

⇒ B=0

⇒ C=2/3

Substituting the values of A, B and C in T(1,0)=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3) ,

T(1,0)=−1/3(1,1,0)+0(0,1,1)+2/3(2,2,3)

Substituting the value of a1 by 0 and a2 by 1 ,

⇒ T(0,1)=(0−1,0,2(0)+1)

=(−1,0,1)

=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3)

Expressing in linear system of equations,

⇒ A+2C=−1

⇒ A+B+2C=0

⇒ B+3C=1

Solving the linear system of equations,

⇒ A=−1

⇒ B=1

⇒ C=0

Substituting the values of A, B and C in T(1,0)=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3),

T(0,1)=−1(1,1,0)+1(0,1,1)+0(2,2,3)

Substituting the value of a1 by 1 and a2 by 2,

⇒ T(1,2)=(1−2,1,2(1)+2)

=(−1,1,4)

=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3)

Expressing in linear system of equations,

⇒ A+2C=−1

⇒ A+B+2C=1

⇒ B+3C=4

Solving the linear system of equations,

⇒ A=−7/3

⇒ B=2

⇒ C=2/3

Substituting the values of A, B and C in T(1,0)=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3),

⇒ T(1,2)=−7/3(1,1,0)+2(0,1,1)+2/3(2,2,3)

Substituting the value of a1 by 2 and a2 by 3,

⇒ T(2,3)=(2−3,2,2(2)+3)

=(−1,2,7)

=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3)

Expressing in linear system of equations,

⇒ A+2C=−1

⇒ A+B+2C=2

⇒ B+3C=7

Solving the linear system of equations,

⇒ A=−11/3

⇒ B=3

⇒ C=4/3

Substituting the values of A, B and C in T(1,0)=A(1,1,0)+B(0,1,1)+C(2,2,3),

⇒ T(2,3)=−11/3(1,1,0)+3(0,1,1)+4/3(2,2,3)

Expressing in matrix form,

Exercise 2.2 Linear Transformations Examples Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 86 Problem 15 Answer

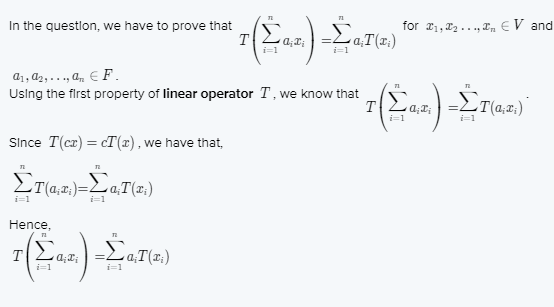

Given: to complete the proof of part (b) of Theorem 2.7

Here, we have to show the commutativity of addition, associativity of addition, additive identity, scalar identity, scalar associativity, scalar distribution and vector distribution to show that S is a vector space.

Let V and W be vector spaces over a field F, and let T, U: V → W be linear.

First assume that a∈F and define T+U:V→W by

⇒ (T+U)(x)=T(x)+U(x), for all x∈V……..(1)

⇒ aT: V→W by

⇒ (aT)(x)=aT(x), for all x∈V………(2).

So the transformation T+U is linear. We will suppose that S is the set of all linear transformations as we defined above. For every transformation T, U in S there exists a unique transformation T+U in S defined by

⇒ (T+U)(x)=T(x)+U(x)

Then for each element a in F, and, each transformation T in S there exists a unique transformation aT in S that is defined by

⇒ (aT)(x)=aT(x) .

commutativity of addition:

Let’s takeT+U, which is for all x∈V defined as,

(T+U)(x)=T(x)+U(x)

Now we get from commutativity of addition

⇒ T(x)+U(x)=U(x)+T(x)=(U+T)(x).

So for all T,U in S,

⇒ T+U=U+T

Associativity of addition:

Take ((T+U)+P)(x). Then, by definition of (1) and from associativity of addition we get

⇒ ((T+U)+P)(x)=(T+U)(x)+P(x)

=((T)(x)+U(x))+P(x)

=T(x)+(U+P)(x)

=(T+(U+P))(x)

So for all T,U,P in S,

⇒ (T+U)+P=T+(U+P).

Additive identity:

We have to prove that there exists a transformation in S, denoted by T0, that is defined as T0(x)=0, such that

⇒ T+T0=T for each T in S.

T0 is here zero transformation and it has the role of zero vectors.

Take (T+T0)(x), so by the definition of (1) we have

⇒ (T+T0)(x)=(T)(x)+T0(x)

=T(x)+0

=T(x)

So, for each T in S,

⇒ T+T0

=T

Additive inverse:

We have to prove that for each T in S, there exists a −T in such that T+(−T)=0.

From the definition (2), for −1∈F and for each T in S, there exists a unique transformation −1⋅T in S defined by,

⇒ (−1⋅T)(x)=−1⋅T(x)

=−T(x)

Now we will take (T+(−T))(x), so by the definition of (1)we have

(T+(−T))(x)=T(x)+(−T)(x)

=T(x)−T(x)

=0(x)

This implies that for each T in S, there exists a −T in S such that

⇒ T+(−T)=0

Scalar identity:

We have to prove that for each T inS,IT=T.

From the definition (2), for I∈F and for each T in S, there exists the unique transformation 1⋅T in S defined by,

⇒ (1⋅T)(x)=1⋅T(x)=T(x)

Scalar Associativity: We have to prove that for each pair of elementsa,b∈∈F, and, for each T in S,a(bT)=(ab)T.

Let’s take a(bT)(x),so from the definition (2) we have.

⇒ a(bT)(x)=a(bT(x))

=ab(T(x))

=((ab)T)(x)

This implies that for each pair of elements a,b∈F and for each T in S

a(bT)=(ab)T

Scalar Distribution:

We have to show that for each element a in F and for each pair of T,U in S,a(T+U)=aT+aU.

Let’s take a((T+U)(x)), so from the definition (1) we have:

⇒ a((T+U)(x))=a(T(x)+U(x))

=a(T(x))+a(U(x))

=(aT(x))+(aU(x))

=(aT+aU)(x)

This implies that for each element a in F and for each pair of T,U in S,

a(T+U)=aT+aU

Vector Distribution:

We have to show that for each pair of elements a,b∈F and for each T in S,(a+b)T=aT+bT. We will take ((a+b)T)(x), and then from the definition (2) we will get

⇒ ((a+b)T)(x)=(a+b)(T(x))

=aT(x)+bT(x)

=(aT+bT)(x)

Hence for each pair of elements a,b∈F and for each T in S,

⇒ (a+b)T=aT+bT

Then from the above showed conditions, we can conclude that S is a vector space.

So the set of all linear transformation defined from the vector space V to the vector space W is a vector space over F

From the above shown conditions, we can conclude that S is a vector space.

So the set of all linear transformations defined from the vector space V to the vector space W is a vector space over F

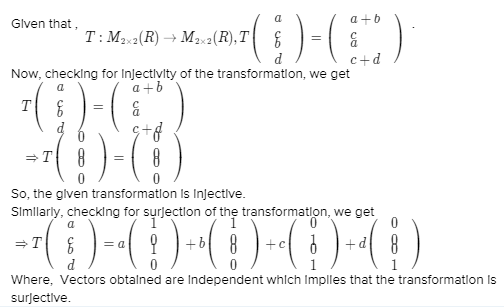

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 86 Problem 16 Answer

Given: Let V be an n-dimensional vector space with an ordered basis β. Define T: V → Fn

byT(x)=[x]β.

To prove that T is linear.

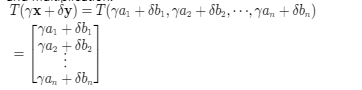

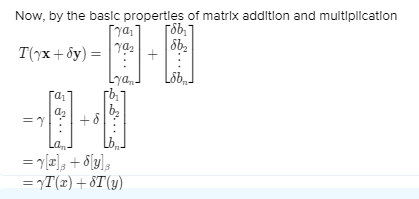

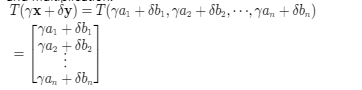

To show that T(γx+δy)=γT(x)+δT(y) for every x,y∈V and γ,δ∈F, use the definition of the transformation T and properties of matrix addition and multiplication.

Let x=(a1,a2,⋯,an)∈V and y=(b1,b2,⋯,bn)∈V.

Also, letγ,δ∈F.

In order to get that T is a linear transformation, we need to show that T(γx+δy)=γT(x)+δT(y).

We will do this using the definition of the transformation T and the basic properties of matrix addition and multiplication.

Hence T is linear.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 86 Problem 17 Answer

Given: Let V be the vector space of complex numbers over the field R.

To define T: V→V by T(z)=zˉ, where zˉ is the complex conjugate of z.

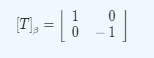

To prove that T is linear, and compute[T]β, where β={1,i}.

Let x=a+ib∈V and y=c+id∈V.

Also, let γ,δ∈R.

We need to show that T(γx+δy)=γT(x)+δT(y), in order to prove that T is a linear transformation.

Using the definition of the transformation T and the basic properties of multiplication and addition of complex numbers, we get the following.

⇒ T(γx+δy)=T[γ(a+ib)+δ(c+id)]

=T[(γa+δc)+(γb+δd)i]

=(γa+δc)−(γb+δd)i

=γ(a−ib)+δ(c−id)

=γx+δy

=γT(x)+δT(y)

Now, let’s compute the matrix [T]β.Therefore, we need to represent T(1) and T(i) as linear combinations of the vectors of the basis β.

⇒ T(1)=T(1+0⋅i)

=1−0⋅i

=1⋅1+0⋅i

⇒ T(i)=T(0+i)

=0−i

=0⋅1+(−1)⋅i

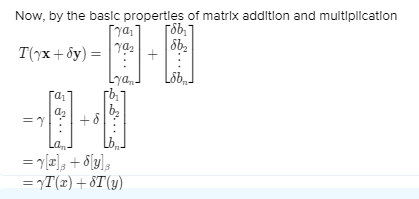

By putting these coefficients into the columns of a 2×2 matrix, we get [T]β.

⇒ [T]β=[1 0 0 −1]

Exercise 2.2 Notes From Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 84 Problem 18 Answer

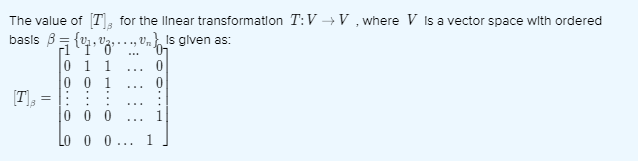

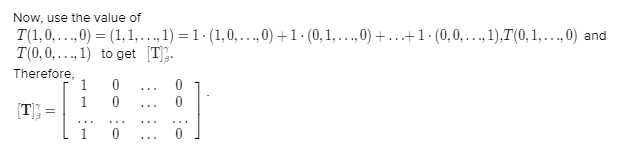

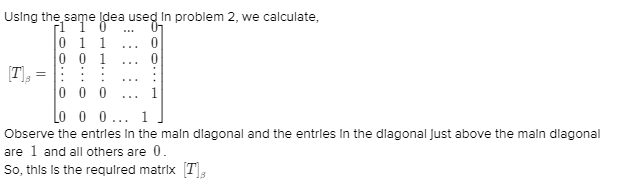

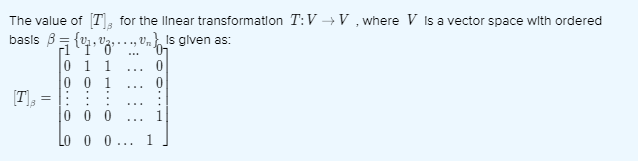

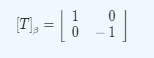

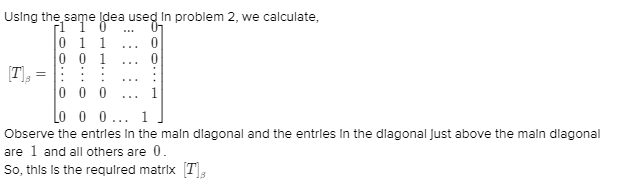

Given: Let V be a vector space with the ordered basis β={v1,v2,…,vn}.

To define v0=0. By Theorem 2.6 there exists a linear transformation T:V→V such that T(vj)=vj+vj−1 for j=1,2,…,n

Compute [T]β

Here,β={v1,v2,…,vn} is the basic of vector space V

v0=0

T:V→V such that T(vj)=vj+vj−1

Therefore,

⇒ v1=v1+v0

⇒ v2=v2+v1

⇒ v3=v3+v2

⇒ v4=v4+v3

⇒ vn=vn+vn−1