Integral Transformations Solved Problems

Example.1 If F=yi+(x-2xz)j-xyk evaluate\(\int_s(\nabla \times \mathbf{F})\) .Nds where S is the surface of the sphere x2+y2+z2=a2 above the XY-plane

Solution:

Given \(\mathbf{F}=y \mathbf{i}+(x-2 x z) \mathbf{j}-x y \mathbf{k}\)

By stokes theorem \(\int_s \nabla \times \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=\int_c \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=\int_c \mathbf{F}_1 d x+\mathbf{F}_2 d y+\mathbf{F}_3 d z\)

= \(\int_c y d x+(x-2 x z) d y-x y d z\)

Above the x y – plane the sphere is \(z=0, x^2+y^2=a^2\)

∴ \(\int_c \mathbf{F} . d \mathbf{r}=\int_c y d x+x d y\) put \(x=a \cos \theta, y=a \sin \theta, d x=-a \sin \theta, d y=a \cos \theta d \theta\) and \(\theta\) varies from 0 to 2π

∴ \(\int_c \mathrm{~F} . d \mathbf{r}=\int_0^{2 \pi}[(a \sin \theta)(-a \sin \theta)+(a \cos \theta)(a \cos \theta)] d \theta\)

= \(a^2 \int_0^{2 \pi} \cos 2 \theta \cdot d \theta=a^2\left[\frac{\sin 2 \theta}{2}\right]_0^{2 \pi}=0\)

Applications Of Stokes’ Theorem In Plane Integral Transformations

Example.2 Prove by Stokes theorem that curl brad Φ=0.

Solution:

Stokes theorem

Let S be a surface enclosed by a simple closed curve C.

∴ By Stokes theorem \(\int_s(curl. \text{grad} \phi). \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=\int_c[\nabla \times(\vee \phi)] . \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=\oint_c \nabla \phi . d \mathbf{r}\)

= \(\int_c\left(\mathbf{i} \frac{\partial \phi}{d x}+\mathbf{j} \frac{\partial \phi}{d y}+\mathbf{k} \frac{\partial \phi}{d z}\right) \cdot(\mathbf{i} d x+\mathbf{j} d y+\mathbf{k} d z)\)

= \(\int_c\left(\frac{\partial \phi}{d x} d x+\frac{\partial \phi}{d y} d y+\frac{\partial \phi}{d z} d z\right)=\int_c d \phi=[\phi]_p^p\) where P is any p t on C=0.

∴ \(\int_c(\text{curl} \text{grad} \phi) \cdot \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=0 \Rightarrow \text{curlgrad} \phi=0\)

Example.3 Verify Stokes theorem for A=(2x-y)i-yz2j-y2zk, where S is the upper half surface of the sphere x2+y2+z2=1 and C is its boundary.

Solution: The boundary C of S is a circle in xy-plane i.e. x+y=1,z=0

The parametric equation. Is x=cos t, y= sin t , z=0 for 0≤ t ≤ 2π

⇒ \(\int_c \mathbf{A} \cdot d \mathbf{r}\)=\(\int_c \mathbf{F}_1 d x+\mathbf{F}_2 d y+\mathbf{F}_3 d z\) = \(\int_c(2 x-y) d x-y z^2 d y-y^2 z d z\)

= \(\int_c(2 x-y) d x\) ∴ \(z=0, d z=0\)

= \(-\int_0^{2 \pi}(2 \cos t-\sin t) \sin t d t=\int_0^{2 \pi} \sin ^2 t d t-\int_0^{2 \pi} \sin 2 t d t\)

= \(4 \int_0^{\pi / 2} \sin ^2 t \cdot d t+\left[\frac{\cos 2 t}{2}\right]_0^{2 \pi}=4 \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{\pi}{2}+\frac{1}{2}(1-1)=\pi\)

Also \(\nabla \times \mathbf{A}=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \\ 2 x-y & -y z^2 & -y^2 z\end{array}\right|\) = k

∴ \(\int_z(\nabla \times \mathbf{A}) \cdot \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=\int_z \mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=\int_R \int d x d y\)

Since \(\mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{N} d \mathbf{S}=d x d y\) and \(\mathbf{R}\) is the projection of S on x y-plane.

Now \(\iint_R d x d y=4 \int_{x=0}^1 \int_{y=0}^{\sqrt{\left(1-x^2\right)}} d y d x=4 \int_0^1 \sqrt{\left(1-x^2\right)} d x\) put \(x=\sin \theta, d x=\cos \theta d \theta\)

= \(4 \int_0^{\pi / 2} \cos ^2 \theta \cdot d \theta=4 \cdot \frac{1}{2} \frac{\pi}{2}=\pi\)

Thus Stokes’s theorem is verified.

Practical Examples Of Stokes’ Theorem In A Plane

Example.4 Verify Sokes theorem for F=-y3 i+x3 j, where S is the circular disc x2+y2≤1, z=0

Solution:

Given \(\mathrm{F}=-y^3 \mathbf{i}+x^3 \mathbf{j}\)

The boundary C of S is a circle in xy-plane

⇒ \(x^3+y^2=1,\)

In parametric form \(x=\cos \theta, y \sin \theta, z=0\) where \(0 \leq \theta \leq 2 \pi\)

∴ \(\int_c \mathrm{~F} . d \bar{r}=\int_c \mathrm{~F}_1 d x+\mathrm{F}_2 d y+\mathrm{F}_3 d z=\int_c\left(-y^3 d x+x^3 d y\right)\)

= \(\int_{2 \pi}^{2 \pi}\left[-\sin ^3 \theta(-\sin \theta)+\cos ^3 \theta \cos \theta\right] d \theta=\int_0^{\pi / 2}\left(1-2 \sin ^2 \theta \cos ^2 \theta\right) d \theta\)

= \(\int_0^{2 \pi} 1 d \theta-2 \int_0^{2 \pi} \sin ^2 \theta \cos ^2 \theta d \theta=2 \pi-2(4) \int_0^2 \sin ^2 \theta \cos ^2 \theta d \theta=2 \pi-8 \cdot \frac{1}{4} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{\pi}{2}=\frac{3 \pi}{2}\)

⇒ \(\nabla \times F=\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

i & j & k \\

\frac{\partial}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \\

-y^3 & x^3 & 0

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(k\left(3 x^2+3 y^2\right)\)

∴ \(\int(\nabla \times \mathrm{F}) \mathbf{N} d \mathrm{~S}=3 \int_s\left(x^2+y^2\right) \mathbf{k} \cdot \mathbf{N} d \mathrm{~S}\)

= \(3 \iint_R\left(x^2+y^2\right) d x d y\)…………(1)

Since \((\mathbf{k} . \mathbf{N}) d \mathrm{~S}=d x d y\) and R is the region of xy – plane

For solving (1) put x = \(r \cos \phi, y=r \sin \phi\)

∴ dx dy = \(r d r d \phi\) and r varies from 0 to 1 and \(0 \leq \phi \leq 2 \pi\)

∴ \(\int(\nabla \times \mathrm{F}) \mathbf{N} d \mathrm{~S}=3 \int_{\phi=0}^{2 \pi} \int_{r=0}^1 r^2 \cdot r d r d \phi=\frac{3 \pi}{2}\),

Hence the verification of the theorem.

Example.5 If F= (y2+z2-x2)i+(z2+x2-y2)j+(x2+y2-z2)k, evaluate ∫curl F.Nds taken over the portion of the surface x2+y2-2ax+az=0 above the plane z=0.

Solution:

Given \(F=\left(y^2+z^2-x^2\right) \mathbf{i}+\left(z^2+x^2-y^2\right) \mathbf{j}+\left(x^2+y^2-z^2\right) \mathbf{k}\)

By Stokes theorem \(\int_S(\nabla \times \mathrm{F}) \cdot \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}=\int_C \mathrm{~F} \cdot d r\)

where C is the circle given by \(x^2+y^2-2 a x=0, z=0\) i.e. \((x-a)^2+y^2=a^2, z=0\)

In parameters the equation of the circle C is

x = \(a+a \cos \theta\),

y = \(a \sin \theta \text {, }\)

z = 0

∴ dx = \(-a \sin \theta d \theta \text {, }\)

dy = \(a \cos \theta d \theta\),

dz=0

∴ \(F. d r=F_1 d x+F_2 d y+F_3 d z\)

= \(\left(y^2+z^2-x^2\right) d x+\left(z^2+x^2-y^2\right) d y+\left(x^2+y^2-z^2\right) d z\)

= \(\left(y^2-x^2\right) d x+\left(x^2-y^2\right) d y\) on the circle C=\(\left(x^2-y^2\right)(d y-d x)\)

= \(\left[(a+a \cos \theta)^2-a^2 \sin ^2 \theta\right][a \cos \theta+a \sin \theta] d \theta\)

= \(a^3\left(1+2 \cos \theta+\cos ^2 \theta-\sin ^2 \theta\right)(\cos \theta+\sin \theta) d \theta\)

∴ \(\int_C F \cdot d r=a^3 \int_0^{2 \pi}\left(1+2 \cos \theta+\cos ^2 \theta-\sin ^2 \theta\right)(\cos \theta+\sin \theta) d \theta\)

= \(a^3 \int_0^{2 \pi}\left(1+2 \cos \theta+\cos ^2 \theta-\sin ^2 \theta\right) \cos \theta d \theta\) the other integrals vanish

= \(2 a^3 \int_0^\pi\left(1+2 \cos \theta+\cos ^2 \theta-\sin ^2 \theta\right) \cos \theta d \theta\)

= \(2 a^3 \int_0^\pi 2 \cos ^2 \theta \cdot d \theta\) the other integrals vanish

= \(8 a^3 \int_0^{\pi / 2} \cos ^2 \theta \cdot d \theta=8 a^3 \frac{1}{2} \cdot \frac{\pi}{2}=2 a^3 \pi\)

Integration Techniques Using Stokes’ Theorem In A Plane

Example.6 Evaluate \( \int_Cy \)dx + z dy + x dz where C is the curve of the Intersection of x2+y2+z2=a2 and x+z=a.

Solution:

y dx+z dy+x dz = \((y \bar{i}+z \bar{j}+x \bar{k}) \cdot(\bar{i} d x+\bar{j} d y+\bar{k} d z)=\bar{F} \cdot d \bar{r}\) where \(\bar{F}=y \bar{i}+z \bar{j}+x \bar{k}\)

by Stokes theorem \(\int_C F \cdot d \bar{r}=\int_S \text{curl} \bar{F} \cdot \overline{\mathrm{N}} d S\)

∴ \(\text{curl} \bar{F}=\nabla \times \bar{F}\) =\(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\bar{i} & \bar{j} & \bar{k} \\

\frac{\partial}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial}{\partial y} & \frac{\partial}{\partial z} \\

y & z & x

\end{array}\right|\) = \(-(\bar{i}+j+\bar{k})\)

Let the projection be taken in xy-plane

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{N}}=\bar{k}\)

∴ \(\int_C \bar{F} \cdot d \bar{r}=-\int_S(\bar{i}+\bar{j}+\bar{k}) \cdot \bar{k} d s=-\int_S d s=-S\)

where S is the surface area of the sphere

⇒ \(\mathrm{S}=4 \pi a^2\)

∴ \(\int \bar{F} . d \bar{r}=-4 \pi a^2\)

Example.7 Prove that \(\oint_c(f \nabla g) \cdot d r\)=\(\int_S[\nabla \times(f \nabla g)] . \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}\)

Solution:

By Stokes theorem \(\oint_c(f \nabla g). d r=\int_S[\nabla \times(f \nabla g)]\). NdS

= \(\int_S[\nabla f \times \nabla g+f \quad curl\quad grad \quad g] \cdot \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}=\int_S(\nabla f \times \nabla g) \cdot \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}\)

Example.8 Prove that\(\int_S \phi \text { curlf. } d S\)=\(=\int_C \phi \mathrm{f} \cdot d r\) – \(\begin{equation}\int_S\end{equation}\) grad Φ ×f.dS

Solution:

Applying Stokes theorem to the function \(\phi \mathrm{f}\)

⇒ \(\int_C \phi \mathrm{f} . d r=\int \text{curl}(\phi f) \cdot \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}=\int_S(\text{grad} \phi \times \mathrm{f}+\phi \text{curlf}) \cdot d S\) using the formula

∴ \(\int_S \phi \text{curl} \mathrm{f} . d \mathrm{~S}=\int_C \phi \mathrm{f} . d r-\int_S \nabla \phi \times \mathrm{f} . d S\)

Vector Calculus Problems Using Stokes’ Theorem

Example.9 Prove that\(\oint_C(f \nabla f) \cdot d r\)=0

Solution:

By Stokes theorem \(\int_{\mathrm{C}}(f \nabla f) \cdot d r=\int_{\mathrm{S}}(\text{curl} f \nabla f) \cdot \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}=\int_{\mathrm{S}}[f \text{curl} \nabla f+\nabla f \times \nabla f] . \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}\)

= \(\int 0 \cdot \mathrm{N} d \mathrm{~S}=0\)

(because curl \(\nabla f=0\) and \(\nabla f \times \nabla f=0\))

Example.10 Verify Stokes’s theorem for F=(y-z+2)i+(yz+4)j-xzk where S is the surface of the cube x=0,y=0,z=0,x=2,y=2,z=2 above the xy-plane.

Solution:

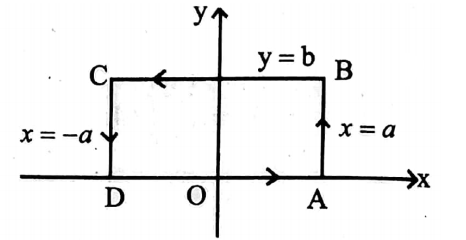

Given \(\mathbf{F}=(y-z+2) \mathbf{i}+(y z+4) \mathbf{j}-x z \mathbf{k}\) where S is the surface of the cube. \(x=0, y=0, z=0\), and x=2, y=2, z=2 above the xy-plane.

By Stoke’s theorem, we have \(\int \text{Curl} \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{n} d s=\int \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}\)

⇒ \(\nabla \times \mathbf{F}\)=\(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

\mathbf{i} & \mathbf{j} & \mathbf{k} \\

\frac{\partial}{\partial x} & \frac{\partial}{\partial y} & \frac{\hat{o}}{\partial z} \\

y-z+2 & y z+4 & -x z

\end{array}\right|\)

= \(\mathbf{i}(0-y)-\mathbf{j}(-z+1)+\mathbf{k}(0-1)=-y \mathbf{i}-(1-z) \mathbf{j}-\mathbf{k}\)

∴ \(\nabla \times \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{n}=\nabla \times \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{k}=(y \mathbf{i}-(1-z) \mathbf{j}-\mathbf{k}) \cdot \mathbf{k}=-1\)

∴ \(\int \nabla \times \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{n} d s=\int_0^2 \int_0^2-1 d x d y\) (because z=0, d z=0) =-4…….(1)

To find \(\int F \cdot d r\)

⇒ \(\int \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=\int((y-z+2) \mathbf{i}+(y z+4) \mathbf{j}-x z \mathbf{k}) \cdot(d x \mathbf{i}+d y \mathbf{j}+d z \mathbf{k})\)

= \(\int[(y-z+2) d x+(y z+4) d y-(x z) d z]\)

S is the surface of the cube above the XY plane

∴ \(z=0 \quad \Rightarrow d z=0\)

∴ \(\int \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=\int(y+2) d x+\int 4 d y\)……(1)

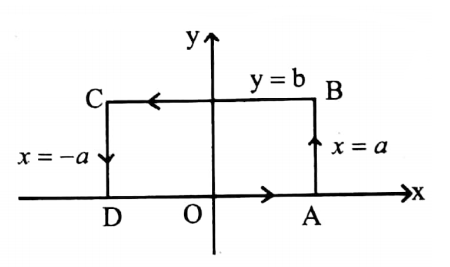

Along \(\overline{O A}, y=0, z=0, d y=0, d z=0, x\) changes from 0 to 2 .

⇒ \(\int_0^2 2 d x=2[x]_0^2=4\)……(2)

Along \(\overline{B C}, y=2, z=0, d y=0, d z=0, x\) changes from 2 to 0 .

⇒ \(\int_2^0 4 d x=4[x]_2^0=-8\)…..(3)

Along \(\overline{A B}, x=2, z=0, d x=0, d z=0, y\) changes from 0 to 2 .

⇒ \(\int \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=\int_0^2 4 d y=[4 y]_0^2=8\)……(4)

Along \(\overline{C O}, x=0, z=0, d x=0, d z=0, y\) changes from 2 to 0 .

⇒ \(\int_2^0 4 d y=-8\)……(5)

Above the surface when z=2

Along \(O^{\prime} A^{\prime}, \int_0^2 \mathbf{F} d \mathbf{r}=0\)….(6)

Along \(A^{\prime} B^{\prime}, x=2, z=2, d x=0, d z=0, y\) changes from 0 to 2 .

⇒ \(\left.\left.\int_0^2 \bar{F} \cdot \bar{r}=\int_0^2(2 y+4) d y=2 \cdot \frac{y^2}{2}\right]_0^2+4 y\right]_0^2=4+8=12\)…..(7)

Along \(B^{\prime} C^{\prime}, y=2, z=2, d y=0, d z=0, x\) changes from 2 to 0 .

⇒ \(\int_2^0 \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=0\)……(8)

Along \(C^{\prime} D^{\prime}, x=0, z=2, d x=0, d z=0, y\) changes from 2 to 0 .

⇒ \(\left.\left.\int_2^0(2 y+4)=2 \cdot \frac{y^2}{2}\right]_2^0+4 y\right]_2^0=-12\)…….(9)

(2)+(3)+(4)+(5)+(6)+(7)+(8)+(9) gives

⇒ \(\int_C \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=4-8+8-8+0+12+0-12=-4\)…..(10)

By Stoke’s theorem, we have \(\int \mathbf{F} \cdot d \mathbf{r}=\int \text{curl} \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathbf{n} d s=-4\)

Hence Stoke’s theorem is verified.