Right Line Representation Of Line

Definition Of A Right Line In Geometry With Examples

1. Consider XZ and XY planes. Their common line of intersection is X-axis.

p(x, y, z) ∈ X-axis <=> P ∈ XY plane and P ∈ XZ plane <=> z = 0 and y = 0

∴ Equations to the line x-axis are y = 0, z = 0 i.e., equations to the plane of the plane passing through the X-axis.

Similarly, equations to y-axis are x = 0, z = 0 i.e., equations to the planes through the y-axis, and equations to z-axis are y = 0, x = 0 i.e., equations to the planes through the z-axis.

2. Consider any line L and two planes π1, π2 whose line of intersection is L.

Let the equations to π1, π2 be respectively

a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 …..(1) a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 …..(2)

P(x, y, z) ∈ L <=> P ∈ π1 and P ∈ π2

<=> a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0

∴ Equations to the line L are a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0

Thus: A line is represented by the equations of two planes through the line. Since any pair of planes can be taken through the line, the pairs of equations of the line are infinitely many.

Right Line Parametric Form

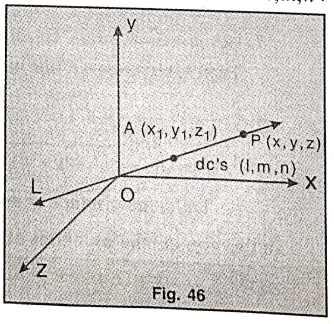

Theorem.1. Equations to the line passing through the point (x1, y1, z1) and having d.cs. l, m, n are x = x1 + lr, y = y1 + mr, z = z1 + nr, r being any real number.

Proof.

Let L be the required line and A (x1, y1, z1). d.cs. of L are l,m,n.

Let P = (x,y,z) ∈ L. Let AP = |r|.

The projection of AP on the x-axis = x – x1 = lr

Similarly y – y1 = mr, z – z1 = nr

⇒ x = x1 + lr, y = y1 + mr, z = z1 + nr r being any real number.

∴ Equations to L are x = x1 + lr, y = y + mr, z = z1 + nr

i.e., \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\)

Note: 1. \(\frac{a_1}{l_1}=\frac{a_2}{l_2}=\frac{a_3}{l_3} \Leftrightarrow a_1: l_1=a_2: l_2=a_3: l_3\) and if any of l’s is zero, the corresponding a is also zero.

2. Equations of the line in the parametric form x = x1 + lr, y = y1 + mr, z = z1 + nr can be written as

⇒ \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}(=r)\)

This form of equations of the line is called the equations of the line in the ‘Symmetric form’.

Let m = 0 = n, l ≠ 0, m ≠ 0. Equations to the line L are y – y1 = 0, z – z1 = 0. Then L represents a line parallel to the x-axis.

Theorem.2. Equations of a line through two distinct points (x1, y1, z1) and (x2, y2, z2) are \(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2-x_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{y_2-y_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{z_2-z_1} \text { or } \frac{x-x_2}{x_2-x_1}=\frac{y-y_2}{y_2-y_1}=\frac{z-z_2}{z_2-z_1}\)

Proof.

Let L be the required line. Since (x1, y1, z1), (x2, y2, z2) ∈ L, d.rs. of L are x2 – x1, y2 – y1, z2 – z1.

∴ Equations to L are \(\frac{x-x_1}{x_2-x_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{y_2-y_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{z_2-z_1} \text { or } \frac{x-x_2}{x_2-x_1}=\frac{y-y_2}{y_2-y_1}=\frac{z-z_2}{z_2-z_1}\)

Theorems Related To Right Lines In Mathematics

Theorem.3. Transform the equations a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 a2x + b2 + cz2 + d2 = 0 of the line of symmetrical form.

Proof.

Let L be the line of intersection of the planes

a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 …(1)

a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 …(2)

Let [l,m,n] be the D.cs. of L.

L lies in both the places (1) and (2).

Since the d.rs. of the normals to the planes are (a1,b1,c1) and (a2,b2,c2) we have a1l + b1m + c1n = 0, a2l + b2m + c2n = 0

⇒ \(\frac{l}{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}=\frac{m}{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}=\frac{n}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}\)

Without loss of generality, we can take a1b2 – a2b1 ≠ 0.

Now to find the equations to L, we require a point on L.

Let L intersect, say, the XY plane i.e. Z = 0 at P.

∴ From (1) and (2): a1x + b1y + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + d2 = 0.

Solving: \(x=\frac{b_1 d_2-b_2 d_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}, y=\frac{d_1 a_2-d_2 a_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}\)

∴ \(\mathrm{P}=\left(\frac{b_1 d_2-b_2 d_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}, \frac{d_1 a_2-d_2 a_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}, 0\right)\) is a point on L.

∴ Equations to L in the symmetric form are

⇒ \(\frac{x-\frac{b_1 d_2-b_2 d_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}}{b_1 c_2-b_2 c_1}=\frac{y-\frac{d_1 a_2-d_2 a_1}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}}{c_1 a_2-c_2 a_1}=\frac{z-0}{a_1 b_2-a_2 b_1}\)

Example. Write the equations of the line x = ay + b and z = cy + d in the symmetrical form.

Solution.

Given

x = ay + b and z = cy + d

Equations of the line L are lx + (-a)y + 0. z = b and ox + cy + (-1)z = -d.

Let d.rs. of the line L be l,m,n.

∴ 1.l + (-a)m + 0(n) = 0, 0.l + cm + (-l)n = 0 i.e., \(\frac{l}{a}=\frac{m}{l}=\frac{n}{c}\)

A point on L is (b,0,d).

∴ L is \(\frac{x-b}{a}=\frac{y-0}{1}=\frac{z-d}{c}\)

OR: Equations to the line are x = ax + b, z = cy + d.

They can be written as \(\frac{x-b}{a}=\frac{y}{1}, \frac{z-d}{c}=\frac{y}{1} \text {. i.e. } \frac{x-b}{a}=\frac{y}{1}=\frac{z-d}{c}\) which form is the symmetrical form of the equations of the line.

Note. If the equations of a line are given as a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0, then the equations of the line are said to be in unsymmetrical form.

Right Line Solved Problems

Example 1. Find the distance of the point (1, -2, 3) from the plane x – y + z = 5 measured parallel to the line whose d.cs. are proportional to 2, 3, -6.

Solution.

Given

The point (1, -2, 3) and the plane x – y + z = 5

Let L be the line through the point P(1, -2, 3) and parallel to the line with d.rs. 2, 3, -6.

∴ Equations to L are \(\frac{x-1}{2}=\frac{y+2}{3}=\frac{z-3}{-6}\) (= t say)

Any point on L is Q(2t + 1, 3t – 2, -6t + 3). Let π be the plane x – y + z = 5.

Q ∈ π ⇒ 2t + 1 – 3t + 2 – 6t + 3 = 5 ⇒ -7t = 1 ⇒ t = (1/7)

∴ \(\mathrm{Q}=\left(\frac{9}{7}, \frac{-11}{7}, \frac{15}{7}\right)\) ∴\( \mathrm{PQ}^2=\left(\frac{9}{7}-1\right)^2+\left(\frac{-11}{7}+2\right)^2+\left(\frac{15}{7}-3\right)^2=\frac{4+9+36}{49}=1\)

∴ Required distance = 1

Example 2. Find the image of the point (2, -1, 3) in the plane 3x – 2y + z = 9.

Solution.

Given

The point (2, -1, 3) and the plane 3x – 2y + z = 9

Let P = (2,-1,3). Let π be the plane 3x – 2y + z = 9.

Let Q = (x1, y1, z1) be the image of P in π.

∴ \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}} \perp \pi\) ∴ Drs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) are 3, -2, 1.

∴ Equation to \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) are \(\frac{x-2}{3}=\frac{y+1}{-2}=\frac{z-3}{1}\) (= t say)

Let R be the midpoint of PQ.

Let R = (3t + 2, -2t -1, t + 3)

R ∈ π ⇒ 9t + 6 + 4t + 2 + t + 3 = 9 ⇒ t = -/frac{1}{7}

∴ R = \(\left(\frac{-3}{7}+2, \frac{2}{7}-1, \frac{-1}{7}+3\right)=\left(\frac{11}{7}, \frac{-5}{7}, \frac{20}{7}\right)\)

R is the midpoint of PQ

⇒ \(2+x_1=\frac{22}{7} \text { i.e., } x_1=\frac{8}{7} ; \quad-1+y_1=\frac{-10}{7}\)

⇒ \(\text { i.e., } y_1=\frac{-3}{7} ; \quad 3+z_1=\frac{40}{7} \text { i.e., } z_1=\frac{19}{7}\)

∴ Q = Image of P in π = \(\left(\frac{8}{7}, \frac{-3}{7}, \frac{19}{7}\right)\)

Solved Exercise Problems On Right Lines Step-By-Step

Example 3. Find the foot of the perpendicular from (1, 2, 3) to the plane x + 2y + 3z + 4 = 0

Solution.

Let the given plane is π = x + 2y + 3z + 4 = 0 …(1)

Given point is P = (1,2,3)

Let the foot of the perpendicular from P to the plane is \(\mathrm{Q}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)\)

Equations of \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}, \frac{x_1-1}{1}=\frac{y_1-2}{2}=\frac{z_1-3}{3}=t \text { (say) }\)

∴ \(x_1=t+1, y_1=2 t+2, z_1=3 t+3\)

Since Q lies on the plane, we have

(t + 1) + 2(2t + 2) + 3(3t + 3) + 4 = 0

⇒ \(14 t+18=0 \Rightarrow t=\frac{-9}{7}\)

⇒ \(x_1=\frac{-9}{7}+1=\frac{-2}{7}, y_1=2 t+2=\frac{-18}{7}+2=-\frac{4}{7}, z_1=3 t+3=\frac{-27}{7}+3=\frac{-6}{7}\)

∴ Foot of the perpendicular = P = \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right)=\left(\frac{-2}{7}, \frac{-4}{7}, \frac{-6}{7}\right)\)

Example 4. Find the angles between the lines x – 2y + z = 0, x + y – z = 3;……L1 x + 2y + z = 5, 8x + 12y + 5z = 0……L2.

Solution.

Let the planes be

x – 2y + z = 0 …(1)

x + y – z = 3 …(2)

x + 2y + z = 5 …(3)

8x + 12y + 5z = 0 …(4)

(1), (2) represent the line L1 and (3), (4) represent the line L2.

The d.rs. of the normals to the planes (1), (2), (3), (4) are (1, -2, 1), (1, 1, -1) (1, 2, 1) and (8, 12, 5) respectively.

If \(\left(I_1, m_1, n_1\right) \text { and }\left(l_2, m_2, n_2\right)\) and the d.rs. of the lines L1 and L2 respectively, \(\left(l_1, m_1, n_1\right)=(2-1,1+1,1+2)=(1,2,3) \text {; }\)

⇒ \(\left(l_2, m_2, n_2\right)=(10-12,8-5,12-16)=(-2,3,-4)\)

∴ D.rs. of L1 are 1, 2, 3, and d.rs. of L2 are -2, 3, -4

If θ is one of the angles between L1, L2 then

⇒ \(\cos \theta=\frac{-2+6-12}{\sqrt{1+4+9} \cdot \sqrt{4+9+16}}=\frac{-8}{\sqrt{406}}\)

∴ \(\left(L_1, L_2\right)={Cos}^{-1}\left(\frac{-8}{\sqrt{(406)}}\right), \pi-{Cos}^{-1}\left(\frac{-8}{\sqrt{(406)}}\right)\)

Example 5. Find the equations to the line L1 passing through the origin and perpendicular to the L2 whose equations are \(\frac{x-2}{1}=\frac{y+3}{-2}=\frac{z}{1}\). Also find the foot of the perpendicular from the origin to L2.

Solution.

Equations to L2 are \(\frac{x-2}{1}=\frac{y+3}{-2}=\frac{z}{1} \quad(=t \text { say })\)

Any point L2 is (t+2, -2t-3, t).

Let P be the foot of the perpendicular from the origin to the line L2.

If P = (t+2, -2t-3,t) then d.rs. of (∵ \(\mathrm{L}_{\mathrm{l}}=\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\)) are t + 2, -2t -3, t.

⇒ \(\mathrm{L}_1 \perp \mathrm{L}_2 \Rightarrow 1(t+2)-2(-2 t-3)+1 t=0 \Rightarrow 6 t=-8 \Rightarrow t=-\frac{4}{3}\)

∴ A foot of the perpendicular from the origin to L2

= \(\left(\frac{-4}{3}+2, \frac{8}{3}-3, \frac{-4}{3}\right)=\left(\frac{2}{3}, \frac{-1}{3}, \frac{-4}{3}\right)\)

∴ Equations to L1 are \(\frac{x-0}{(2 / 3)}=\frac{y-0}{(-1 / 3)}=\frac{z-0}{(-4 / 3)} \text { i.e., } \frac{x}{2}=\frac{-y}{1}=\frac{-z}{4}\)

Properties Of Right Lines With Examples And Solutions

Example 6. A variable plane makes intercepts on the axes, the sum of whose squares is k2 (a constant). Show that the locus of the foot of the perpendicular from origin to the plane is (x-2 + y-2 + z-2)(x2 + y2 + z2)2 = k2

Solution.

Given

A variable plane makes intercepts on the axes, the sum of whose squares is k2 (a constant)

π is a variable plane \(\frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1 \quad(a b c \neq 0)\)

⇒ intercepts of π on the axes are a, b, c ⇒ \(a^2+b^2+c^2=k^2 \text { (given) }\) …(1)

D.rs. of normal to π are \(\frac{1}{a}, \frac{1}{b}, \frac{1}{c}\)

Let L be the line through O and perpendicular to π.

∴ Equations to L are \(\frac{x}{1 / a}=\frac{y}{1 / b}=\frac{z}{1 / c}(=t \text { say }) .\)

∴ Any point P on L is \(\left(\frac{t}{a}, \frac{t}{b}, \frac{t}{c}\right) .\)

P is the foot of the perpendicular from O to π

⇒ P ∈ π ⇒ \(\frac{t}{a^2}+\frac{t}{b^2}+\frac{t}{c^2}=1 \Rightarrow t=\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1}\)

∴ \(\mathbf{P}=\left(a^{-1}\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1}, b^{-1}\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1}, c^{-1}\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1}\right) \text {. }\)

P = \(\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right) \Rightarrow x_1=a^{-1}\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1} ; y_1=b^{-1}\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1} \text {; }\)

⇒ \(z_1=c^{-1}\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1} \text {. }\)

⇒ \(x_1^2+y_1^2+z_1^2=\left[\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1}\right]^2\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)=\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^{-1} \text { and }\)

⇒ \(x_1^{-2}+y_1^{-2}+z_1^{-2}=\left(a^{-2}+b^{-2}+c^{-2}\right)^2\left(a^2+b^2+c^2\right)\)

⇒ \(\left(x_1^{-2}+y_1^{-2}+z_1^{-2}\right)=\frac{1}{\left(x_1^2+y_1^2+z_1^2\right)^2} \cdot k^2\) [using (1)]

⇒ \(\left(x_1^{-2}+y_1^{-2}+z_1^{-2}\right)\left(x_1^2+y_1^2+z_1^2\right)^2=k^2\)

∴ Locus of P is \(\left(x^{-2}+y^{-2}+z^{-2}\right)\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^2=k^2\)

Example 7. The plane lx + my + nz = p, l2 + m2 + n2 = 1, p > 0 meets the axes in P, Q, R and G is the centroid of the △PQR, If the perpendicular line to the plane at G meets the coordinate planes in A, B, C then prove that \(\frac{1}{\mathrm{GA}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{~GB}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{GC}}=\frac{3}{p}\)

Solution.

Given

The plane lx + my + nz = p, l2 + m2 + n2 = 1, p > 0 meets the axes in P, Q, R and G is the centroid of the △PQR, If the perpendicular line to the plane at G meets the coordinate planes in A, B, C

Let π be the plane lx + my + nz = p, \(l^2+m^2+n^2=1\).

π meets the axes in P, Q, R.

∴ \(\mathrm{P}=\left(\frac{p}{l}, 0,0\right), \mathrm{Q}=\left(0, \frac{p}{m}, 0\right), \mathrm{R}=\left(0,0, \frac{p}{n}\right)\)

∴ Centroid G of △PQR = (p/3l, p/3m, p/3n)

Let L be the line perpendicular to π at G.

∴ Equations to L are \(\frac{x-(p / 3 l)}{l}=\frac{y-(p / 3 m)}{m}=\frac{z-(p / 3 n)}{n}\) (=t say)

L meets the YZ plane i.e. x = 0 in A.

∴ \(|t|=\mathrm{GA}=\left|\frac{0-(p / 3 l)}{l}\right|=\left|\frac{-p}{3 l^2}\right| \text { i.e., } \frac{1}{\mathrm{GA}}=\frac{3 l^2}{p}(p>0)\)

Similarly \(\frac{1}{\mathrm{~GB}}=\frac{3 m^2}{p} \text { and } \frac{1}{\mathrm{GC}}=\frac{3 n^2}{p}\)

∴ \(\frac{1}{\mathrm{GA}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{~GB}}+\frac{1}{\mathrm{GC}}=\frac{3 l^2+3 m^2+3 n^2}{p}=\frac{3}{p}\)

Right Line Angle Between A Line And A Plane

Theorem.4. If θ is the acute angle between the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) and the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0, then \(\sin \theta=\pm \frac{a l+b m+c n}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2} \sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\)

Proof.

Let L be the given line and E be the given plane.

The d.rs. of L are (l, m, n) and the d.rs. of the normal to E are (a, b, c).

Since θ is the acute angle between L and E, the angles between L and normal to E are 90° ± θ

⇒ \(\cos (90 \pm \theta)= \pm \sin \theta=\frac{a l+b m+c n}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2} \sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\)

⇒ \(\sin \theta= \pm \frac{a l+b m+c n}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2} \sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\)

Right Line Conditions For A Line To Lie In A Plane

Theorem.5. If L is the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) and π is the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0, then L ⊂ π <=> a1x + b1y + c1z + d = 0, al + bm + cn = 0.

Proof.

Any point P on L is \(\left(x_1+l r, y_1+m r, z_1+n r\right)\) where r is any real number.

L ⊂ π ⇔ P ∈ π

⇔ \(a\left(x_1+l r\right)+b\left(y_1+m r\right)+c\left(z_1+n r\right)+d=0 \text { for any real number }\)

⇔ \(\left(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d\right)+r(a l+b m+c n)=0\) for any real number r

⇔ \(a x_1+b y_1+c z_1+d=0, a l+b m+c n=0\)

Note.1. A-line lies in a plane if

(1) any point on the line lies in the plane, and

(2) the normal to the plane is perpendicular to the line.

2. Equation to a plane containing the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) can be taken as a(x – x1) + b(y – y1) + c(z – z1) = 0 where a, b, c are parameters such that al + bm + cn = 0.

3. The line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) is parallel to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 and not contained in the plane ⇒ al + bm + cn = 0 and ax1 + by1 + cz1 ≠ 0.

4. The line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) is perpendicular to the plane ax + by + cz + d = 0 ⇒ \(\frac{l}{a}=\frac{m}{b}=\frac{n}{c}\)

Right Line Solved Problems

Example.1. Find the equation to a plane through the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) and parallel to another line with d.cs. l2, m2, n2.

Solution.

Equation to the plane through the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) can be taken as

⇒ \(l\left(x-x_1\right)+m\left(y-y_1\right)+n\left(z-z_1\right)=0\) …(1)

where \(l l_1+m m_1+m n_1=0\) …(2)

If (1) is parallel to another line with d.cs. l2, m2, n2

then \(l l_2+m m_2+n n_2=0\) …(3)

∴ From (2) and (3), \(\frac{l}{m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1}=\frac{m}{n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1}=\frac{n}{l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1} \quad \text { (= Ksay) }\)

∴ The equation to the required plane is

⇒ \(\left(m_1 n_2-m_2 n_1\right)\left(x-x_1\right)+\left(n_1 l_2-n_2 l_1\right)\left(y-y_1\right)+\left(l_1 m_2-l_2 m_1\right)\left(z-z_1\right)=0\)

i.e. \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\)

(may also be obtained by eliminating l, m, n from (1), (2), (3))

Step-By-Step Guide To Solving Right Line Problems In Geometry

Example.2. Find the equation to the plane through the line \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\) and through the point (x1, y1, z1)

Solution.

Let L be the line \(\frac{x-x_2}{l}=\frac{y-y_2}{m}=\frac{z-z_2}{n} .\)

∴ L passes through the point (x2, y2, z2).

Let π be the plane containing the line L and passing through the point (x1, y1, z1).

Let the equation to the plane π be \(a\left(x-x_2\right)+b\left(y-y_2\right)+c\left(z-z_2\right)=0\) …(1)

where al + bm + cn = 0 …(2)

Also \(a\left(x_1-x_2\right)+b\left(y_1-y_2\right)+c\left(z_1-z_2\right)=0\) …(3)

Eliminating a, b, c from (1), (3), and (2), the equation to the plane π is

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_2 & y-y_2 & z-z_2 \\

x_1-x_2 & y_1-y_2 & z_1-z_2 \\

l & m & n

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Example.3. Find the equation of the plane through the origin and containing the line x – 3y + 2z + 3 = 0 = 3x – y + 2z – 5.

Solution.

Given line is x – 3y + 2z + 3 = 0 = 3x – y + 2z – 5.

Any plane through the given line is x – 3y + 2z + 3 + λ(3x – y + 2z – 5) = 0

If it passes through the origin, then 0 + 3 + λ(0-5) = 0 ⇒ λ = 3/5

∴ Equation to the required plane is x – 3y + 2z + 3 + (3/5)(3x – y + 2z – 5) = 0 i.e. 7x – 9y + 8z = 0.

Example.4. Find the equation of the plane that passes through the line a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 = a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 and is parallel to the line \(\frac{x}{l}=\frac{y}{m}=\frac{z}{n}\)

Solution.

Let the plane through the line \(a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1=0=a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2\) and parallel to \(\frac{x}{l}=\frac{y}{m}=\frac{z}{n} \text { be } a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1+\lambda\left(a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2\right)=0\) where

\(\left(a_1+\lambda a_2\right) l+\left(b_1+\lambda b_2\right) m+\left(c_1+\lambda c_2\right) n=0\)i.e., \(\lambda=-\frac{l a_1+m b_1+n c_1}{l a_2+m b_2+n c_2},\left(l a_2+m b_2+n c^2 \neq 0\right)\)

∴ The equation to the required plane is

⇒ \(\left(l a_2+m b_2+n c_2\right)\left(a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1\right)-\left(l a_1+m b_1+n c_1\right)\left(a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2\right)=0\)

Examples Of Right Line Problems In 2d And 3d Geometry

Example.5. A = (a, 0, 0), B = (0, b, 0), C = (0, 0, c) and P = (a, b, c) are points distinct from O such that P2 = a2 + b2 + c2 (p > 0) and q-2 = a-2 + b-2 + c-2 (q > 0). If θ is the acute angle between \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}}\) show that \(\sin \theta=\frac{3 q}{p}\).

Solution.

Equation to the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}} \text { is } \frac{x}{a}+\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1 \text {. }\)

D.rs. of its normal are (1/a), (1/b), (1/c).

D.rs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}\) are a, b, c.

∴ \(\theta=(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OP}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{ABC}})\)

⇒ \(\sin \theta=\frac{a \cdot \frac{1}{a}+b \cdot \frac{1}{b}+c \cdot \frac{1}{c}}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2} \cdot \sqrt{\left(1 / a^2\right)+\left(1 / b^2\right)+\left(1 / c^2\right)}} \Rightarrow \sin \theta=\frac{3}{p \cdot \frac{1}{q}}=\frac{3 q}{p}\)

Right Line Coplanarity Of Lines

Theorem.6. L1, L2 are lines whose equations are \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) …..(1)\(\frac{x-x_2}{l_2}=\frac{y-y_2}{m_2}=\frac{z-z_2}{n_2}\)….(2). L1, L2 are coplanar ⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x_1-x_2 & y_1-y_2 & z_1-z_2 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Proof:

First Method.

An equation to the plane containing line (1) is

⇒ \(a\left(x-x_1\right)+b\left(y-y_1\right)+c\left(z-z_1\right)=0\) …(3)

with the condition that \(a l_1+b m_1+c n_1=0\) …(4)

where not all a, b, c are zero.

The line (2) lies on the plane (3) if (1) the point \(\left(x_2, y_2, z_2\right)\) lies on (3)

⇒ \(a\left(x_2-x_1\right)+b\left(y_2-y_1\right)+c\left(z_2-z_1\right)=0\) …(5)

and (2) the line (2) is perpendicular to the normal to the plane (3)

⇒ a l_2+b m_2+c n_2=0 …(6)

The given lines (1) and (2) are coplanar if the three linear homogeneous equations (4), (5), (6) in a, b, c are consistent.

Eliminating a, b, c from the equations (4), (5), (6) we get

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x_2-x_1 & y_2-y_1 & z_2-z_1 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\) …(7)

This is the condition for the lines (1) and (2) be coplanar.

Theorem.7. Equation to the plane containing the line L1 with equations \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) and parallel to the line L2 with equations \(\frac{x-x_2}{l_2}=\frac{y-y_2}{m_2}=\frac{z-z_2}{n_2}\) is \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Proof.

The lines are \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) …(1)

⇒ \(\frac{x-x_2}{l_2}=\frac{y-y_2}{m_2}=\frac{z-z_2}{n_2}\) …(2)

the equation to the plane containing the line (1) is

⇒ \(a\left(x-x_1\right)+b\left(y-y_1\right)+c\left(z-z_1\right)=0\) …(3)

with the condition \(a l_1+b m_1+c n_1=0\) …(4) where not all a, b, c are zero.

The plane (3) will be parallel to the line (2),

if \(a l_2+b m_2+c n_2=0\) …(5)

We obtain the equation to the required plane by eliminating a, b, c from (3), (4), (5)

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Worked Examples Of Right Line Problems In Analytical Geometry

Theorem.8. L1, L2 are lines whose equations are \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\)……(1) \(\frac{x-x_2}{l_2}=\frac{y-y_2}{m_2}=\frac{z-z_2}{n_2}\)…..(2) Then equation to the plane containing L1, L2 is \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Proof.

First Method. The equations to the lines L1, L2 are

⇒ \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) …(1)

⇒ \(\frac{x-x_2}{l_2}=\frac{y-y_2}{m_2}=\frac{z-z_2}{n_2}\) …(2)

the equation to the plane containing the line L1is

⇒ \(a\left(x-x_1\right)+b\left(y-y_1\right)+c\left(z-z_1\right)=0\) …(3)

with the condition \(a l_1+b m_1+c n_1=0\) …(4)

if L2 lies in (3) then \(a l_2+b m_2+c n_2=0\) …(5)

Eliminating a, b, c from (3), (4), (5) we get \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x-x_1 & y-y_1 & z-z_1 \\

l_1 & m_1 & n_1 \\

l_2 & m_2 & n_2

\end{array}\right|=0\)

this is the equation to the plane containing the lines L1 and L2

Theorem.9. If the lines \(\frac{x-\alpha}{l}=\frac{y-\beta}{m}=\frac{z-\gamma}{n}\).….(1) a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 = 0 = a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 ……(2) are coplanar, then \(\frac{a_1 \alpha+b_1 \beta+c_1 \gamma+d_1}{a_1 l+b_1 m+c_1 n}=\frac{a_2 \alpha+b_2 \beta+c_2 \gamma+d_2}{a_2 l+b_2 m+c_2 n}\)

Proof.

Any plane through the line (2) is

⇒ \(\lambda_1\left(a_1+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1\right)+\lambda_2\left(a_2 y+c_2 z+d_2\right)=0 \text {, and } \lambda_1, \lambda_2\) being any scalars such that

⇒ \(\left(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\right) \neq(0,0) \text {. i.e., }\left(\lambda_1 a_1+\lambda_2 a_2\right) x+\left(\lambda_1 b_1+\lambda_2 b_2\right) y+\left(\lambda_1 c_1+\lambda_2 c_2\right) z+\left(\lambda_1 d_1+\lambda_2 d_2\right)=0\)

If the line (1) were to lie in this plane, then

⇒ \(\lambda_1\left(a_1 \alpha+b_1 \beta+c_1 \gamma+d_1\right)+\lambda_2\left(a_2 \alpha+b_2 \beta+c_2 \gamma+d_2\right)=0\) …(3)

⇒ \(\left(\lambda_1 a_1+\lambda_2 a_2\right) l+\left(\lambda_1 b_1+\lambda_2 b_2\right) m+\left(\lambda_1 c_1+\lambda_2 c_2\right) n=0\)

i.e., \(\lambda_1\left(a_1 l+b_1 m+c_1 n\right)+\lambda_2\left(a_2 l+b_2 m+c_2 n\right)=0\) …(4)

From (3) and (4), since \(\left(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\right) \neq(0,0),\) we have

⇒ \(\frac{a_1 \alpha+b_1 \beta+c_1 \gamma+d_1}{a_1 l+b_1 m+c_1 n}=\frac{a_2 \alpha+b_2 \beta+c_2 \gamma+d_2}{a_2 l+b_2 m+c_2 n}\)

Online Resources For Right Line Theorems And Solved Problems

Theorem.10. Condition for the lines in unsymmetrical form a1x + b1y + c1z + d1 =0, a2x + b2y + c2z + d2 = 0 ……(1) a3x + b3y + c3z + d3 = 0, a4x + b4y + c4z + d4 = 0 …..(2) to be coplanar is that \(\left|\begin{array}{llll}

a_1 & b_1 & c_1 & d_1 \\

a_2 & b_2 & c_2 & d_2 \\

a_3 & b_3 & c_3 & d_3 \\

a_4 & b_4 & c_4 & d_4

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Proof.

Equation to a plane containing the line (1) can be taken as

⇒ \(\lambda_1\left(a_1 x+b_1 y+c_1 z+d_1\right)+\lambda_2\left(a_2 x+b_2 y+c_2 z+d_2\right)=0 \text {, }\)

⇒ \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) being any scalars such that (\(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\)) ≠ (0,0).

i.e., \(\left(\lambda_1 a_1+\lambda_2 a_2\right) x+\left(\lambda_1 b_1+\lambda_2 b_2\right) y+\left(\lambda_1 c_1+\lambda_2 c_2\right) z+\left(\lambda_1 d_1+\lambda_2 d_2\right)=0\)

Similarly equation to a plane containing the line (2) can be taken as

⇒ \(\left(\lambda_3 a_3+\lambda_4 a_4\right) x+\left(\lambda_3 b_3+\lambda_4 b_4\right) y+\left(\lambda_3 c_3+\lambda_4 c_4\right) z+\left(\lambda_3 d_3+\lambda_4 d_4\right)=0\)

⇒ \(\lambda_3, \lambda_4\) being any scalars such that (\(\lambda_3, \lambda_4\)) ≠ (0,0).

If (1) and (2) are coplanar, then \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3, \lambda_4\) can be so chosen to make the equations (3), (4) represent the same plane.

For λ ≠ 0,

⇒ \(\lambda_1 a_1+\lambda_2 a_2=\lambda\left(\lambda_3 a_3+\lambda_4 a_4\right) \Rightarrow \lambda_1 a_1+\lambda_2 a_2+\left(-\lambda \lambda_3\right) a_3+\left(-\lambda \lambda_4\right) a_4=0,\)

⇒ \(\lambda_1 b_1+\lambda_2 b_2=\lambda\left(\lambda_3 b_3+\lambda_4 b_4\right) \Rightarrow \lambda_1 b_1+\lambda_2 b_2+\left(-\lambda \lambda_3\right) b_3+\left(-\lambda \lambda_4\right) b_4=0 \text {, }\)

⇒ \(\lambda_1 c_1+\lambda_2 c_2=\lambda\left(\lambda_3 c_3+\lambda_4 c_4\right) \Rightarrow \lambda_1 c_1+\lambda_2 c_2+\left(-\lambda \lambda_3\right) c_3+\left(-\lambda \lambda_4\right) c_4=0\)

⇒ \(\lambda_1 d_1+\lambda_2 d_2=\lambda\left(\lambda_3 d_3+\lambda_4 d_4\right) \Rightarrow \lambda_1 d_1+\lambda_2 d_2+\left(-\lambda \lambda_3\right) d_3+\left(-\lambda \lambda_4\right) d_4=0\)

If these equations are to have a non-zero solution

i.e. \(\left(\lambda_1, \lambda_2, \lambda_3, \lambda_4\right) \neq(0,0,0,0)\), then

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{llll}

a_1 & a_2 & a_3 & a_4 \\

b_1 & b_2 & b_3 & b_4 \\

c_1 & c_2 & c_3 & c_4 \\

d_1 & d_2 & d_3 & d_4

\end{array}\right|=0 \text { i.e., }\left|\begin{array}{llll}

a_1 & b_1 & c_1 & d_1 \\

a_2 & b_2 & c_2 & d_2 \\

a_3 & b_3 & c_3 & d_3 \\

a_4 & b_4 & c_4 & d_4

\end{array}\right|=0\)

Right Line Number Of Arbitrary Constants Or Parameters In The Equation Of A Line

Consider the following equations of a line L in the symmetrical form \(\frac{x-x_1}{l}=\frac{y-y_1}{m}=\frac{z-z_1}{n}\). Let m ≠ 0, n ≠ 0.

The equations to L can be expressed as

⇒ \(x=\left(\frac{l}{m}\right) y+\left(\frac{m x_1-l y_1}{m}\right), x=\left(\frac{1}{n}\right) z+\left(\frac{n x_1-l z_1}{n}\right)\)

i.e., x = ay + b, x = cz + d where a, b, c, d are arbitrary constants.

Here the plane x = ay + b is parallel to the z-axis and the plane x = cz + d is parallel to the y-axis. Thus the equations to the line L always be expressed in terms of two first-degree equations with not more than four arbitrary constants.

Now to determine a line we consider various sets of given conditions by which we can evaluate the arbitrary constants in the equations to the line. For instance, when the line

(1) Passes through a given point and has a given direction (d.rs.)

(2) Passes through two given points.

(3) Passes through a given point and is parallel to two given planes.

(4) Passes through two given points and perpendicular to two given planes.

(5) Passes through a given point and intersects two given lines.

(6) Intersects two given lines and has a given direction.

(7) Passes through a given point and is intersecting a given line at right angles.

(8) Is intersecting two given lines at right angles.

Right Line Line Coplanar With Two Lines

Consider two non-coplanar lines u1 = 0 = v1 and u2 = 0 = v2.

For (λ1,µ1) ≠ (0,0) and (λ2,µ2) ≠ (0,0), the line λ1u1 + µ1v1 = 0 = λ2u2 + µ2v2 lies in the plane λ1u1 + µ1v1 = 0 which again contains the line u1 = 0 = v1.

The two lines λ1u1 + µ1v1 = 0 = λ2u2 + µ2v2; u1 = 0 = v1 are therefore, coplanar.

Similarly the two lines λ1u1 + µ1v1 = 0 = λ2u2 + µ2v2; u2 = 0 = v2 are coplanar.

Thus, λ1u1 + µ1v1 = 0 = λ2u2 + µ2v2 is the line coplanar with both the lines u1 = 0 = v1 ; u2 = 0 = v2

Right Line Solved Problems

Example.1. Show that the lines \(\frac{x}{l}=\frac{y}{m}=\frac{z}{n}, \frac{x}{a \alpha}=\frac{y}{b \beta}=\frac{z}{c \gamma}, \frac{x}{\alpha}=\frac{y}{\beta}=\frac{z}{\gamma}\) are coplanar if \(\frac{l}{\alpha}(b-c)+\frac{m}{\beta}(c-a)+\frac{n}{\gamma}(a-b)=0\)

Solution.

D.rs. of the line \(\frac{x}{l}=\frac{y}{m}=\frac{z}{n}\) are l, m, n.

∴ A vector along the line is (l, m, n).

Similarly vectors along the lines \(\frac{x}{a \alpha}=\frac{y}{b \beta}=\frac{z}{c \gamma}, \frac{x}{\alpha}=\frac{y}{\beta}=\frac{z}{\gamma}\) are respectively (aα, bβ, cγ), (α, β, γ).

The three given lines are coplanar

⇒ the vectors (l, m, n), (aα, bβ, cγ), (α, β, γ) are coplanar

⇒ [(l, m, n), (aα, bβ, cγ), (α, β, γ)]

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

l & m & n \\

a \alpha & b \beta & c \gamma \\

\alpha & \beta & \gamma

\end{array}\right|=0 \Rightarrow \operatorname{l\beta \gamma }(b-c)+m \gamma \alpha(c-a)+n \alpha \beta(a-b)=0\)

⇒ \(\frac{l}{\alpha}(b-c)+\frac{m}{\beta}(c-a)+\frac{n}{\gamma}(a-b)=0\)

Right Line Equations And Their Geometric Interpretations

Example.2. Prove that the lines \(\frac{x+1}{1}=\frac{y+1}{2}=\frac{z+1}{3}\) and x + 2y + 3z – 8 = 0 = 2x + 3y + 4z – 11 are intersecting and find the point of their intersection. Find also the equation to the plane containing them.

Solution.

Given lines are \(\frac{x+1}{1}=\frac{y+1}{2}=\frac{z+1}{3}\) …(1)

x + 2y + 3z – 8 = 0 = 2x + 3y + 4z – 11 …(2)

Any point P on (1) is (r-1, 2r-1, 3r-1)

If P lies on the first plane containing the line (2), r – 1 + 4r – 2 + 9r – 3 – 8 = 0 i.e., 14r = 14 i.e., r = 1.

∴ P = (0,1,2). Clearly P also lies on the plane 2x + 3y + 4z – 11 = 0

∴ (1) and (2) intersect at the point P (0,1,2)

A plane through the line (2) is x + 2y + 3z – 8 + k (2x + 3y + 4z – 11) = 0

i.e., (1 + 2k)x + (2+3k)y + (3+4k)z – (8+11k) = 0.

If this plane is parallel to (1), 1(1+2k) + 2(2+3k) + 3(3+4k) = 0

i.e., 20k = -14 i.e., k = -(7/10).

∴ The equation to the plane containing line (2) and parallel to (1) is \(x+2 y+3 z-8-\frac{7}{10}(2 x+3 y+4 z-11)=0\)

i.e. -4x – y + 2z – 3 = 0 i.e. 4x + y – 2z + 3 = 0.

This plane clearly contains the point (-1, -1, -1)

∴ 4x + y – 2z + 3 = 0 is the plane containing the lines (1) and (2).

Note.1. If the point (-1, -1, -1) on the base (1) does not lie on the plane 4x + y – 2z + 3 = 0 then 4x + y – 2z + 3 = 0 is the plane containing the line (2) and parallel to line(1).

2. To show that the lines (1) and (2) are coplanar, find the point of intersection of (1) and (2) or find the plan containing the line (2) and the line (1).

Example.3. Prove that \(\frac{x+4}{3}=\frac{y+6}{5}=\frac{z-1}{-2}\) and 3x – 2y + z + 5 = 0 = 2x + 3y + 4z -4 are coplanar. Find the point of intersection

Solution.

Given lines are \frac{x+4}{3}=\frac{y+6}{5}=\frac{z-1}{-2}=t \text { (say) } …(1)

and 2x + 3y + 4z – 4 = 0 = 3x – 2y + z + 5 …(2)

Any point P on (1) is P = (3t – 4, 5t – 6, -2t + 1)

If P lies on the 1st plane of (2), we get

3(3t – 4) – 2(5t – 6) + (-2t + 1) + 5 = 0

⇒ 9t – 12 – 10t + 12 – 2t + 1 + 5 = 0 ⇒ -3t + 6 = 0 ⇒ t = 2.

∴ p = (2, 4, -3)

Clearly, P lies in the second plane of line (2)

∴ The lines (1) & (2) intersect the point (2, 4, -3).

Hence the two lines are coplanar.

Example.4. Find the equations of the line through the origin and intersect each of the lines \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1} \text { and } \frac{x-x_2}{l_2}=\frac{y-y_2}{m_2}=\frac{z-z_2}{n_2}\)

Solution.

Given lines are \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) …(1)

⇒ \(\frac{x-x_1}{l_1}=\frac{y-y_1}{m_1}=\frac{z-z_1}{n_1}\) …(2)

Let the equation to the plane containing (1) be

⇒ \(a\left(x-x_1\right)+b\left(y-y_1\right)+c\left(z-z_1\right)=0\) …(3)

∴ \(a l_1+b m_1+c n_1=0\) …(4)

If the plane (3) passes through the origin, then

⇒ \(-a x_1-b y_1-c z_1=0 \text { i.e. } a x_1+b y_1+c z_1=0\) …(5)

Solving (4) and (5), \(\frac{a}{m_1 z_1-n_1 y_1}=\frac{b}{n_1 x_1-l_1 z_1}=\frac{c}{l_1 y_1-m_1 x_1}\) .

∴ Equation to the plane containing the line (1) and passing through the origin is \(a x+b y+c z=a x_1+b y_1+c z_1\)

i.e. \(\left(m_1 z_1-n_1 y_1\right) x+\left(n_1 x_1-l_1 z_1\right) y+\left(l_1 y_1-m_1 x_1\right) z=0\) …(6) [using (5)].

Similarly, the equation to the plane containing the line (2) passing through the origin is \(\left(m_2 z_2-n_2 y_2\right) x+\left(n_2 x_2-l_2 z_2\right) y+\left(l_2 y_2-m_2 x_2\right) z=0\) …(7)

∴ (6) and (7) represent the required line.

Example.5. Find the equations of the line through the point (1, 1, 1) and intersect the lines 2x – y – z – 2 = 0 = x + y + z – 1; x – y – z = 0 = 2x + 4y – z – 4.

Solution.

Given lines are 2x – y – z – 2 = 0, x + y + z – 1 = 0 …(1)

x – y – z – 3 = 0, 2x + 4y – z – 4 = 0 …(2)

Let the equation to the plane containing (1) and passing through (1,1,1) be (2x – y – z – 2)+λ(x + y + z – 1) = 0.

∴ (2 – 1 – 1 – 2) + λ(1 + 1 + 1 -1) = 0 i.e. λ = 1.

∴ required plane is x – 1 = 0.

Let the equation to the plane containing (2) and passing through (1,1,1) be (x – y – z – 3) + μ(2x + 4y – z – 4) = 0.

∴ (1 – 1 – 1 -3) + μ(2 + 4 – 1 – 4) = 0 i.e. μ = 4

∴ Required plane is 9x + 15y – 5z – 19 – 0.

∴ Equations of the required line are x – 1 = 0, x + 15y – 5z – 19 = 0

i.e. x – 1 = 0, 15(y – 1) = 5(z – 1) i.e. \(x-1=0, \frac{y-1}{1}=\frac{z+1}{3}\)

Example.6. Find the equations of the straight line passing through the point (1, 0, -1) and intersecting the lines 4x – y – 13 = 0 = 3y – 4z – 1; y – 2z + 2 = 0 = x -5.

Solution.

Equations of given lines are

4x – y – 13 = 0, 3y – 4z – 1 = 0 …(1) and

y – 2z + 2 = 0, x – 5 = 0 …(2)

equations of planes passing through (1), (2) are

⇒ \((4 x-y-13)+\lambda_1(3 y-4 z-1)=0\) …(3)

⇒ \((y-2 z+2)+\lambda_2(x-5)=0\) …(4)

If the planes (3), (4) pass through (1,0,-1) substitute the points in (3), (4) we have \(\lambda_1=3, \lambda_2=1\), then equations of the planes passing through (1, 0, -1) and containing (1), (2) are given by x + 2y – 3z – 4 = 0 and x + y – 2z – 3 = 0 …(5)

converting these equations into symmetric form we get

⇒ \(\frac{x-0}{1}=\frac{y+1}{1}=\frac{z+2}{1} \text { (or) } x=y+1=z+2\)

Example.7. Find the equations of the line with d.cs. proportional to 7, 4, -1 which intersects the lines x-1= -9 + 3y = 3z + 6, \(\frac{x+3}{-3}=\frac{y-3}{2}=\frac{z-5}{4}\)

Solution.

Given lines are \(\frac{x-1}{3}=\frac{y-3}{1}=\frac{z+2}{1}=p\) …(1)

⇒ \(\frac{x+3}{-3}=\frac{y-3}{2}=\frac{z-5}{4}=q\) …(2)

A point P on (1) is (3p + 1, p + 3, p – 2) and a point Q on (2) is (-3q -3, 2q + 3, 41 + 5)

D.rs. of \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\), are (3p + 3q + 4, p – 2q, p – 4q – 7)

If \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{PQ}}\) is the required line, then

⇒ \(\left.\begin{array}{r}

3 p+3 q+4=7 \text { i.e. } \quad p+q=1 \\

+p-2 q=4 \text { i.e. }+p-2 q=4

\end{array}\right\}\)

∴ p = 2, q = -1 and these values satisfy p – 4q = 6

p – 4q – 7 = -1 i.e. p – 4q = 6.

∴ p = (7,5,0) and Q = (0,1,1)

∴ Equations to the required line are \(\frac{x-7}{7}=\frac{y-5}{4}=\frac{z}{-1} \text { or } \frac{x}{7}=\frac{y-1}{4}=\frac{z-1}{-1}\)

Example.8. Find the equations of the line intersecting the line 2x + y – 1 = 0 = x – 2y + 2z; 3x – y + z + 2 = 0 = 4x + 5y – 2z -3 and is parallel to the line \(\frac{x-1}{1}=\frac{y-2}{2}=\frac{z-3}{3}\).

Solution.

Let the equations to the required line be

2x + y – 1 + λ(x – 2y + 3z) = 0, (3x – y + z + 2) + μ(4x + 5y – 2z – 3) = 0

i.e. (2 +λ )x + (1-2λ)y + 3λz – 1 = 0, (3+4μ)x + (-1+5μ) + (1-2μ)z + 2 – 3μ = 0

since the required line is parallel to \(\frac{x-1}{1}=\frac{y-2}{2}=\frac{z-3}{3}\), we have

⇒ \(1(2+\lambda)+2(1-2 \lambda)+3(3 \lambda)=0,1(3+4 \mu)+2(-1+5 \mu)+3(1-2 \mu)=0\)

i.e. λ = -2/3, μ = -1/2

∴ Equations of the required line are 4x + 7y – 6z = 3, 2x – 7y + 4z = -7

Right Line Shortest Distance Between Two Skew Lines

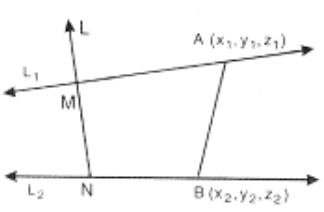

Skew Lines. Any two non-parallel and non-intersecting lines are called skew lines. Skew lines are non-coplanar.

Let L1, L2 be two skew lines. We know that there exists one and only one line L intersecting L1, L2 such that L1 ⊥ L2 and L1 ⊥ L2. Let L intersect L1 at M and L2 at N so that MN is the line segment on L and in between L1, L2. Also MN is the shortest distance (S.D) between L1, L2 and \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{MN}}(=\mathrm{L})\) is the line of S.D. Let A, B are any two points on L1, L2.

⇒ \(\overline{\mathrm{MN}}=|| \overline{\mathrm{AB}}|\cos (\overline{\mathrm{MN}}, \overline{\mathrm{AB}})|=\overline{\mathrm{AB}}|\cos (\overline{\mathrm{MN}}, \overline{\mathrm{AB}})| \leq \overline{\mathrm{AB}}\)

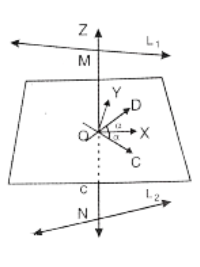

Right Line Equations Of Two Skew Lines In A Simplified Form

L1, L2 are two skew lines and MN be the line of S.D. between them. Let O be the mid point of MN.

Let \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OC}} \| \mathrm{L}_1 \text { and } \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OD}} \| \mathrm{L}_2\). In the plane \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{COD}}\), let \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OX}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OY}}\) be the bisectors of angles between \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OC}}, \overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{OD}}\) so that \(\overline{\mathrm{OX}}\) is the bisector of \((\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OC}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OD}})\)

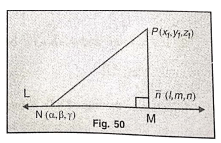

Right Line Length Of The Perpendicular From To A Line

Theorem.11. If L is the line \(\frac{x-\alpha}{l}=\frac{y-\beta}{m}=\frac{z-\gamma}{n}\) and P=(x1, y1, z1), then length of the perpendicular from P to \(L=\frac{1}{\sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\left[\sum\left\{m\left(z_l-\gamma\right)-n\left(y_1-\beta\right)\right\}^2\right]^{1 / 2}\)

Right Line Solved Problems

First Method.

Proof.

Let M be the projection of P in L.

Let N be the point (α, β, γ) on L.

P = [atex]\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \mathrm{NP}=\sqrt{\sum\left(x_1-\alpha\right)^2}[/latex]

△PMN is a right-angled triangle.

D.cs. of NM are \(\left(\frac{l}{\sqrt{\sum l^2}}, \frac{m}{\sqrt{\sum l^2}}, \frac{n}{\sqrt{\sum l^2}}\right)\)

NM = Projection of PN on the given line

= \(\frac{l\left(x_1-\alpha\right)+m\left(y_1-\beta\right)+n\left(z_1-\gamma\right)}{\sqrt{\sum l^2}}\)

= \(\mathrm{PM}^2=\mathrm{PN}^2-\mathrm{NM}^2=\Sigma\left(x_1-\alpha\right)^2-\left[\frac{\sum l\left(x_1-\alpha\right)}{\sqrt{\Sigma l^2}}\right]^2\)

= \(\frac{\left(\sum l^2\right)\left(\sum{\overline{x_1-\alpha}}^2\right)-\sum l\left(x_1-\alpha\right)^2}{\sqrt{\Sigma l^2}}=\frac{\left[\Sigma\left(m\left(z_1-\alpha\right)-n\left(y_1-\beta\right)^2\right]^{1 / 2}\right.}{\sqrt{\Sigma l^2}}\)

Second Method.

Proof.

Let M be the projection of P in L. Let N be the point (α, β, γ) on L. Since \(\mathrm{P}=\left(x_1, y_1, z_1\right), \overline{\mathrm{NP}}=\left(x_1-\alpha, y_1-\beta, z_1-\gamma\right)\). △PMN is a right-angled triangle.

Let \(\bar{n}\) be a unit vector along \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{NM}}\) so that \(\bar{n}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}(l, m, n) .\)

PM = \(\mathrm{NP} . \sin \angle \mathrm{PNM}=|\bar{n}||\overline{\mathrm{NP}}| \sin (\overline{\mathrm{NP}}, \bar{n})=\left|\bar{n} \times \frac{\sqrt{1}+m}{\mathrm{NP}}\right|\)

= \(\left|\frac{1}{\sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}(l, m, n) \times\left(x_1-\alpha, y_1-\beta, z_1-\gamma\right)\right|\)

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\left|\left(m \overline{z_1-\gamma}-n \overline{y_1-\beta}, n \overline{x_1-\alpha}-l \overline{z_1-\gamma}, m \overline{x_1-\alpha}-l \overline{y_1-\beta}\right)\right|\)

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{I^2+m^2+n^2}}\left|\left(m \overline{z_1-\gamma}-n \overline{y_1-\beta}, n \overline{x_1-\alpha}-\mid \overline{z_1-\gamma}, m \overline{x_1-\alpha}-l \overline{y_1-\beta}\right)\right|\)

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\left[\sum\left\{m\left(z_1-\gamma\right)-n\left(y_1-\beta\right)\right\}^2\right]^{1 / 2}\)

∴ Length of the perpendicular from P to L

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{l^2+m^2+n^2}}\left[\sum\left\{m\left(z_1-\gamma\right)-n\left(y_1-\beta\right)\right\}^2\right]^{1 / 2}\)

Note. Length of the perpendicular from P to L is \(|\bar{n} \times \overline{\mathrm{NP}}|=\frac{|\overline{\mathrm{NM}} \times \overline{\mathrm{NP}}|}{|\overline{\mathrm{NM}}|}\)

Example.1. Find the distance between the straight lines \(\frac{x-3}{1}=\frac{y-5}{-2}=\frac{z-7}{1} ; \frac{x+1}{7}=\frac{y+1}{-6}=\frac{z+1}{1}\)

Solution.

Equations of given straight lines are \(\frac{x-3}{1}=\frac{y-5}{-2}=\frac{z-7}{1} ; \frac{x+1}{7}=\frac{y+1}{-6}=\frac{z+1}{1}\)

Let \(\frac{x-3}{1}=\frac{y-5}{-2}=\frac{z-7}{1}=r_1 \text { and } \frac{x+1}{7}=\frac{y+1}{-6}=\frac{z+1}{1}=r_2\)

Any point on (1) is \(P\left(r_1+3,-2 r_1+5, r_1+7\right)\)

Any point on (2) is \(Q\left(7 r_2-1,-6 r_2-1, r_2-1\right)\)

Dr’s of PQ are \(\left(r_1+3\right)-\left(7 r_2-1\right),\left(-2 r_1+5\right)-\left(-6 r_2-1\right),\left(r_1+7\right)-\left(r_2-1\right)\)

i.e., \(\left(n_1-7 r_2+4,-2 n+6 r_2+6, n-r_2+8\right)\)

Let PQ be the shortest distance between (1), (2) then PQ is perpendicular to (1), (2)

⇒ \(\left(r_1-7 r_2+4\right) \cdot 1+\left(-2 r_1+6 r_2+6\right)(-2)+\left(r_1-r_2+8\right) \cdot 1=0\)

⇒ \(\eta_1+4 \eta_1+\eta_1-7 r_2-12 r_2-r_2+4-12+8=0\)

⇒ \(6 r_1-20 r_2=0 \Rightarrow 3 r_1-10 r_2=0\) …(3)

and \(\left(r_1-7 r_2+4\right)(7)+\left(-2 r_1+6 r_2+6\right)(-6)+\left(r_1-r_2+8\right) \cdot 1=0\)

⇒ \(7 r_1+12 n_1+r_1-49 r_2-36 r_2-r_2+28-36+8=0 \Rightarrow 20 r_1-86 r_2=0\)

⇒ \(10 n_1-43 m_2=0\) …(4)

on solving (3), (4) r1 = r2 = 0

Co-ordinates of D: (3,5,7) and Co-ordinates of Q :(-1, 1, -1)

The shortest distance between (1), (2) is

⇒ \(P Q=\sqrt{(3+1)^2+(5+1)^2+(7+1)^2}=\sqrt{16+36+64}=\sqrt{116}=2 \sqrt{29} \text { units. }\)

Example.2. Find the length and equations of the line of S.D. between the lines \(\frac{x}{1}=\frac{y}{2}=\frac{z}{1}\) and x + y + 2z -3 = 0 = 2x + 3y + 3z – 4.

Solution.

Given lines are \(\frac{x}{1}=\frac{y}{2}=\frac{z}{1}\) …(1)

and x + y + 2z – 3 = 0 …(2)

2x + 3y + 3z – 4 = 0 …(3)

A plane through the second line and parallel to (1) is x + y + 2z – 3 + λ(2x + 3y + 3z – 4) = 0 …(4)

i.e., (1 + 2λ)x + (1 + 3λ)y + (2 + 3λ)x – 3 – 4λ = 0.

∴ \(1(1+2 \lambda)+2(1+3 \lambda)+1(2+3 \lambda)=0 \Rightarrow 11 \lambda=-5 \Rightarrow \lambda=-\frac{5}{11}\)

∴ From (4), the equation to the plane through the second line and parallel to (1) is x – 4y + 7z – 13 = 0

A point on (1) is (0,0,0) …(5)

∴ S.D. between the lines = Distance of (0,0,0) from (5) = \(\left|\frac{-13}{\sqrt{1+16+49}}\right|=\frac{13}{\sqrt{(66)}}\)

The equation to the plane through the first line and perpendicular to (5) is

⇒ \(\left|\begin{array}{ccc}

x & y & z \\

1 & 2 & 1 \\

1 & -4 & 7

\end{array}\right|=0 \quad \text { i.e., } 3 x-y-z=0\) …(6)

Let a plane through the second line be x+y+2 z-3+\lambda_1(2 x+3 y+3 z-4)=0

i.e., \(\left(1+2 \lambda_1\right) x+\left(1+3 \lambda_1\right) y+\left(2+3 \lambda_1\right) z-3-4 \lambda_1=0\)

If this plane is perpendicular to (5),

⇒ \(\left(1+2 \lambda_1\right) x+\left(1+3 \lambda_1\right) y+\left(2+3 \lambda_1\right) z-3-4 \lambda_1=0\)

∴ From (4), the equation to the plane through the second line and perpendicular to (5) is x + 2y + z – 1 = 0

Example.3. Show that the equation to the plane containing the line \(\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}=1, x=0\) and parallel to the line \(\frac{x}{a_1}-\frac{z}{c}=1, y=0 \text { is } \frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}-\frac{z}{c}+1=0\) and if 2d is S.D., prove that \(\frac{1}{d^2}=\frac{1}{a^2}+\frac{1}{b^2}+\frac{1}{c^2}\)

Solution.

Given lines are \(\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}-1=0, x=0\) …(1)

and \(\frac{x}{a}-\frac{z}{c}=1, y=0\) …(2)

The line (2) can be written as \(\frac{x-a}{a}=\frac{z}{c}, y=0\)

A plane through the line (1) is \(\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}-1+\lambda x=0.\)

If this is parallel to (2), then \(\lambda \cdot a+\frac{1}{b} \cdot 0+\frac{1}{c}, c=0 \Rightarrow \lambda=-\frac{1}{a}\)

∴ The equation to the plane containing the line (1) and parallel to (2) is

⇒ \(\frac{y}{b}+\frac{z}{c}-1-\frac{1}{a} x=0 \text { i.e., } \frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}-\frac{z}{c}+1=0 \text {. }\)

A point on the line (2) is (a,0,0).

Since 2d is the S.D. between (1) and (2), therefore

2d = distance of (a,0,0) from the \(\frac{x}{a}-\frac{y}{b}-\frac{z}{c}+1=0\)

⇒ \(2 d=\left|\frac{\frac{a}{a}-\frac{0}{b}-\frac{0}{c}+1}{\sqrt{\frac{1}{a^2}+\frac{1}{b^2}+\frac{1}{c^2}}}\right| \Rightarrow \frac{1}{d^2}=\frac{1}{a^2}+\frac{1}{b^2}+\frac{1}{c^2}\)

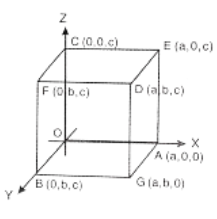

Example.4. a, b, c are the lengths of the edges of a rectangular parallelopiped. Prove that the S.D. between the diagonals and the edges not n=meeting them are \(\frac{b c}{\sqrt{b^2+c^2}}, \frac{c a}{\sqrt{c^2+a^2}}, \frac{a b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2}}\)

Solution.

Let (OBGA; CFDE) be the rectangular parallelopiped with edges a, b, c

Let \(\overrightarrow{\mathrm{OA}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OB}}, \overrightarrow{\mathrm{OC}}\) be the axes.

∴ A = (a,0,0), B = (0,b,0), C = (0,0,c)

Equation to \(\overleftrightarrow{\mathrm{GC}} is \frac{x-0}{a}=\frac{y-0}{b}=\frac{z-c}{-c}\)

A point on this line L2 is (3r+1, -3r+2, 10r-3). If this point lies on π, then 3(3r+1)-3(-3r+2)+10(10r-3)-26 = 0 ⇒ r = (1/2)

∴ The foot of (1,2,-3) in π is \(\left(\frac{3}{2}+1, \frac{-3}{2}+2,10 \times \frac{1}{2}-3\right) \text { i.e. }\left(\frac{5}{2}, \frac{1}{2}, 2\right)\)

If (x1, y1, z1) is the image of (1,2,-3) in π, then

⇒ \(\frac{1+x_1}{2}=\frac{5}{2}, \frac{2+y_1}{2}=\frac{1}{2}, \frac{-3+z_1}{2}=2 \Rightarrow x_1=4, y_1=-1, z_1=7\)

∴ The image of (1,2,-3) in π is (4, -1, 7).

∴ The line through the points \(\left(-\frac{525}{6},-\frac{47}{6}, \frac{159}{6}\right)\), (4,-1,7) is the image of the line L1 and its equation is i.e. \(\frac{x-4}{549}=\frac{y+1}{41}=\frac{z-7}{-117}\)

Example.5. Find the length of the perpendicular from the point (1, 2, 3) to the line through the point (6, 7, 7) whose d.rs. are 3, 2, -2. (or) Find the perpendicular distance of the point (1, 2, 3) from the line \(\frac{x-6}{3}=\frac{y-7}{2}=\frac{z-7}{-2}\)

Solution.

Let L be the line through (6, 7, 7) with d.rs. 3, 2, -2.

∴ Equation to L is \(\frac{x-6}{3}=\frac{y-7}{2}=\frac{z-7}{-2}\) (=r, say)

Let P = (1,2,3) and N = (6,7,7).

∴ \(\overline{\mathrm{NP}}=(5,5,4)\)

Let \(\bar{n}\) be a unit vector along L.

Since d.rs. of L are 3, 2, -2, we have \(\bar{n}=\left(\frac{3}{\sqrt{(17)}}, \frac{2}{\sqrt{(17)}}, \frac{-2}{\sqrt{(17)}}\right)\)

∴ Length of the perpendicular from P to L.

= \(|\overline{\mathrm{NP}} \times \bar{n}|=\left|(5,5,4) \times \frac{3,2,-2}{\sqrt{(17)}}\right|\)

= \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{(17)}}|-18,22,-5|=\frac{\sqrt{324+484+25}}{\sqrt{(17)}}=\sqrt{\frac{833}{17}}=7\)

OR: Let Q ∈ L and Q = (3r + 6, 2r + 7, -2r + 7)

If PQ ⊥ then 3(3r + 6 – 1) + 2(2r + 7 – 2) -2(-2r + 7 3) = 0

Since \(\overline{\mathrm{PQ}}=(3 r+6-1,2 r+7-2,-2 r+7-3)\)

∴ 17r = -17 i.e., r = -1

∴ Q = (3, 5, 9)

∴ PQ = \(\sqrt{4+9+36}=7\)