Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Linear Transformations and Matrices

Page 96 Exercise 1 Answer

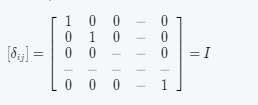

Given: statement is, If A is a square matrix and Aij=δij for all i and j, then

⇒ A=I.

We have,

δij={0,i≠j1,i=j

So, in the case of matrices, we interpret it as [δij]={aij=0,i≠jaij=1,i=j.

So,herefore, the given statement is true.

In view of linear transformation it is confirmed that, If A is a square matrix and Aij=δij for all i and j, then A=I statement is true.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 2 Answer

Read and Learn More Stephen Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition Solutions

Stephen Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition Solutions For Exercise 2.3 Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 96 Exercise 3 Answer

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 4 Answer

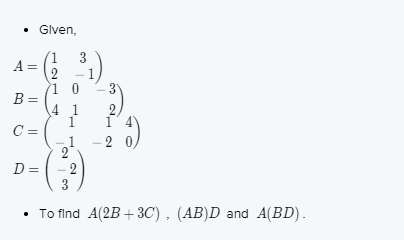

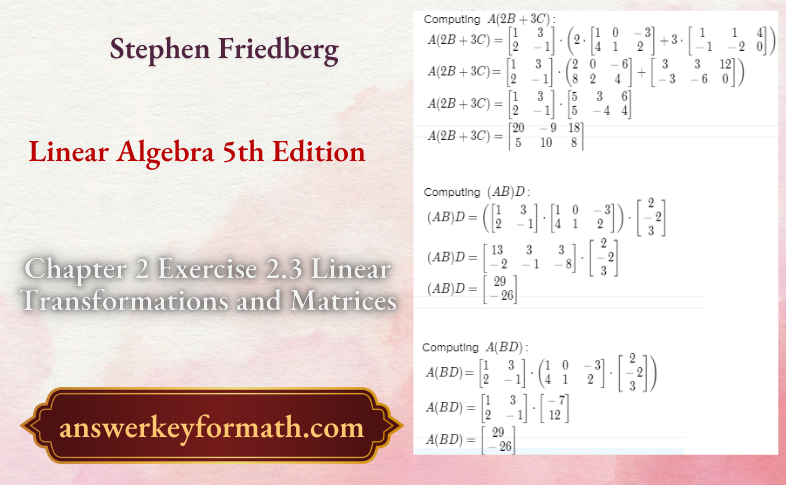

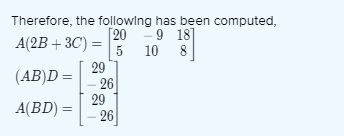

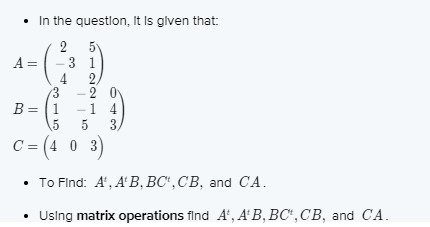

Given,

⇒ g(x)=3+x

⇒ T: P2

⇒ (R)→P2

⇒ (R)T(f(x))=f′

⇒ (x)g(x)+2f(x)

⇒ U: P2

⇒ (R)→R3

⇒ U(a+bx+cx2)=(a+b,c,a−b)

⇒ β={1,x,x2}

⇒ γ={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

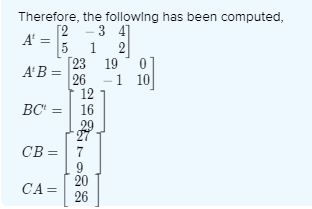

To compute [U]βγ,[T]β, and [UT]βγ.

Verify the result using Theorem 2.11.

Represent U(T(f(x))), U and T in matrix form.

Compute [U]βγ,[T]β, and [UT]βγ.

Using the Theorem 2.11, verify [UT]αγ=[U]βγ[T]αβ.

Given,

⇒ g(x)=3+x

⇒ T:P2(R)→P2(R)T(f(x))=f′(x)g(x)+2f(x)

⇒ U:P2(R)→R3U(a+bx+cx2)=(a+b,c,a−b)

⇒ β={1,x,x2}

⇒ γ={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

Let, f(x)=a+bx+cx2∈P2(R)

Then,

⇒ T(f(x))=(b+2cx)(3+x)+2(a+bx+cx2)

=3b+6cx+bx+2cx2+2a+2bx+2cx2

=(2a+3b)+(3b+6c)x+(4c)x2

This implies,U(T(f(x)))=(2a+3b)+(3b+6c)x+(4c)x2

Representing U(T(f(x))) in matrix form,

⇒ UT(1)=(2,0,2)

⇒ UT(2)=(6,0,0)

⇒ UT(3)=(6,4,−6)

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 5 Answer

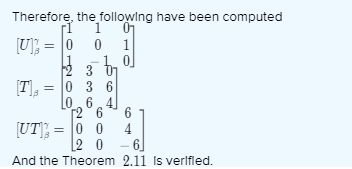

In the question, it is given that: g(x)=3+x

⇒ h(x)=3−2x+x2

⇒ T:P2(R)→P2(R)T(f(x))=f′(x)g(x)+2f(x)

⇒ U:P2(R)→R3U(a+bx+cx2)=(a+b,c,a−b)

⇒ β={1,x,x2}γ={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

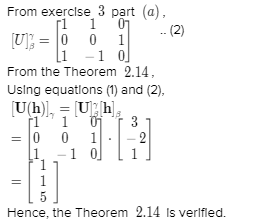

To Find: [h(x)]β and [U(h(x))]γ. Verify the result using Theorem.

First, calculate U(h(x)) and [h(x)]β.

Then verify the Theorem 2.14.

Given,

⇒ g(x)=3+x

⇒ h(x)=3−2x+x2

⇒ T:P2(R)→P2(R)T(f(x))=f′(x)g(x)+2f(x)

⇒ U:P2(R)→R3U(a+bx+cx2)=(a+b,c,a−b)

⇒ β={1,x,x2}

⇒ γ={(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)}

Now,

⇒ U(h(x))=U(3−2x+x2)=(1,1,5)

Representing U(h(x)) in matrix form,[U(h(x))]γ=

[1]

[1]

[5]

Also, representing [h(x)]βin matrix form,

[h(x)]β=[3−21] .. (1)

Therefore, the following have been computed[h(x)]β=

[3]

[−2]

[1]

[U(h(x))]γ=

[1]

[1]

[5]

And the Theorem 2.14 is verified.

Exercise 2.3 Linear Transformations Solved Examples Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 6 Answer

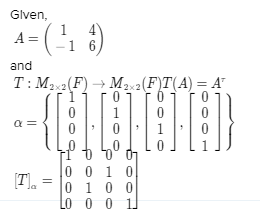

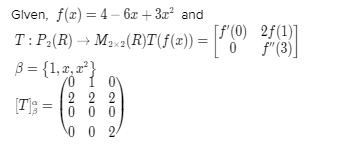

Given, T be a linear transformation and

A=

(1)

(−1)

(4)

(6).

To compute [T(A)]α.

Obtain [T]α.

Using Theorem 2.14 compute [T(A)]α.

Therefore, using theorem 2.14,

[T(A)]α=

[1]

[−1]

[4]

6].

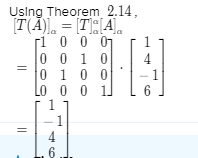

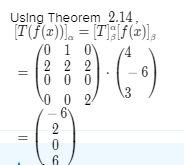

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 7 Answer

Given, T be a linear transformation andf(x)=4−6x+3×2.

To compute [T(f(x))]α.

Obtain [T]βα.

Using Theorem 2.14 compute [T(f(x))]α.

Therefore, using theorem 2.14,[T(f(x))]α=

[−6]

[2]

[0]

6].

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 8 Answer

In the question, it is given that T be a linear transformation and A=

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4).

To Find: [T(A)]γ.

First obtain [T]αγ.

Then, use Theorem 2.14 to compute [T(A)]γ.

GivenA=

(1)

(2)

(3)

)4) and

T: M2×2

(F)→FT(A)=tr(A)γ={1}[T]αγ=

(1)

(0)

(0)

1).

Using Theorem 2.14,

[T(A)]γ=[T]αγ[A]α

Therefore, using theorem 2.14,

[T(A)]γ=(5).

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 97 Exercise 9 Answer

In the question, it is given that T be a linear transformation and f(x)=4−6x+3×2.

To Find: [T(f(x))]γ.

Obtain [T]βγ.

Using Theorem 2.14 compute [T(f(x))]γ.

Given, f(x)=6−x+2×2 and T:P2(R)→RT(f(x))=f(2)

βγ=

[1]

[2]

[4]

Using Theorem 2.14,

⇒ [T(f(x))]γ=[T]βγ[f(x)]β

=[124]⋅[6−12]

=[12]

Therefore, using theorem 2.14,

[T(f(x))]γ=[12].

Linear Algebra Friedberg Exercise 2.3 Step-By-Step Solutions Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 10 Answer

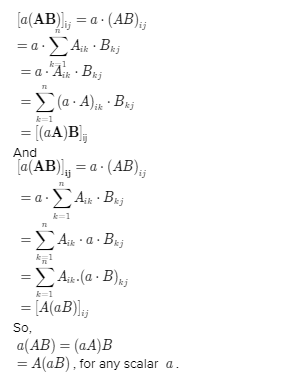

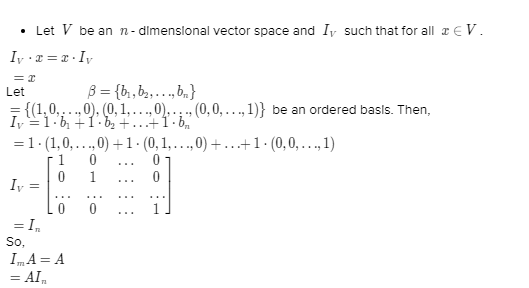

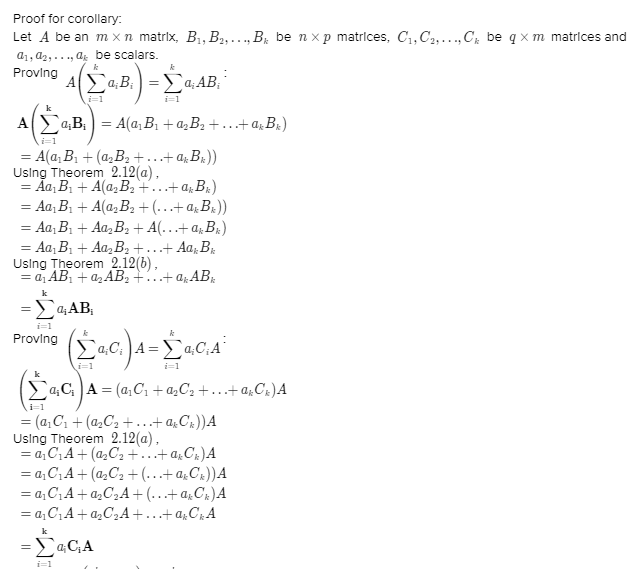

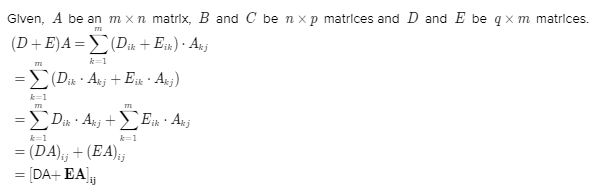

Given, A be an m×n matrix, B and C be n×p matrices and D and E be q×m matrices.

To complete the proof of Theorem 2.12 and its corollary.

To prove the Theorem 2.12 (a), (b) and (d).

Prove corollary of Theorem 2.12.

So, (D+E)A=DA+EA.

So, A(i=1∑kaiBi)=i=1∑kaiABi and

(i=1∑kaiCi)A=i=1∑kaiCiA.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 11 Answer

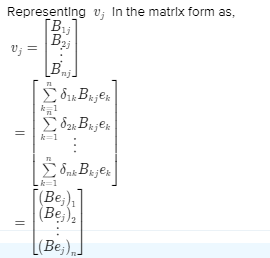

Proving Theorem 2.13(b).Given, A be an m×n matrix and B be an n×p matrix. For each j(1≤j≤p) let uj and vj denote the jth columns of AB and B, respectively.

To prove Theorem 2.13(b).

Given, A be an m×n matrix and B be an n×p matrix. For each j(1≤j≤p) let uj and vj denote the jth columns of AB and B, respectively.

This implies,vj

=[B1j]

[B2j]

⋮

[Bnj]

Representing the elements of vj as,

⇒ B1j=0⋅B11+0⋅B12+…0⋅B1j−1+1⋅B1j+0⋅B1j+1+…+0⋅B1n

⇒ B2j=0⋅B21+0⋅B22+…0⋅B2j−1+1⋅B2j+0⋅B2j+1+…+0⋅B2n

⋮

⇒ Bnj

=0⋅Bn1+0⋅Bn2+…0⋅Bnj−1+1⋅Bnj+0⋅Bnj+1+…+0⋅Bnn

Therefore, vj=Bej where ej is the jth standard vector of Fp is proved.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 12 Answer

In the question, it is given that A be an m × n matrix with entries from F .

Then the left-multiplication transformation LA: Fn → Fm is linear. Furthermore, if B is any other m × n matrix (with entries from F ) and β and γ are the standard ordered bases for Fn and Fm, respectively.

We are asked to prove Theorem 2.15(c) and 2.15(d).

Use the definition of left multiplication transformation.

Given, A be an m × n matrix with entries from F .

Then the left-multiplication transformation LA : Fn → Fm is linear.

Furthermore, if Bis any other m × n matrix (with entries from F ) and β and γ are the standard ordered bases for Fn and Fm , respectively.

From the definition,

LA+B(x)=(A+B)x=Ax+Bx=LA(x)+LB(x)

Also,

LaA(x)=(aA)x=a{Ax}=a{LA(x)}=aLA(x)

Therefore,LA+B=LA+LB and LaA=aLA for all a∈F

Consider, LIn(x)=Inx=x .. (1)

By the definition of left – multiplication transformation.

Using the identity transformation,

IFn(x)=x .. (2) Where, IFn is the identity transformation on the vector space Fn.

Therefore, from equations (1) and (2),

LIn=IFn

Therefore, Theorem 2.15(c) and Theorem 2.15(d) has been proved.

Exercise 2.3 Matrices Examples Friedberg Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 13 Answer

Given, V be a vector space. Let T,U1,U2∈L(V).

To prove Theorem 2.10 and giving a more general result.

Proving Theorem 2.10using a more general result involving linear transformations with domains unequal to their codomains.

Given, V be a vector space. Let T,U1,U2∈L(V).

From, T(U1+U2)=TU1+TU2 it implies,

(T(U1+U2))(x)=T(U1(x)+U2(x))(T(U1+U2))(x)=T(U1(x))+T(U2(x))(T(U1+U2))(x)=(TU1+TU2)(x)

Therefore, T(U1+U2)=TU1+TU2

And (U1+U2)T=U1T+U2T it implies,

(U1+U2)T(x)=U1(Tx)+U2(Tx)(U1+U2)T(x)=(U1T)(x)+(U2T)(x)(U1+U2)T(x)=(U1T+U2T)(x)

Therefore, (U1+U2)T=U1T+U2T

Now,

T(U1U2)(x)=T(U1(U2(x)))T(U1U2)(x)=(TU1)(U2(x))T(U1U2)(x)=(TU1)U2(x)

Therefore, T(U1U2)=(TU1)U2.

Clearly,

TI(x)=T(I(x))

TI(x)=T(x)

So, TI=T

Also, IT(x)=I(T(x))

=T(x)

This implies, IT=T

Therefore, TI=IT=T

Consider,

a(U1U2)(x)=aU1(U2(x))a(U1U2)(x)=(aU1)(U2(x))a(U1U2)(x)=((aU1)U2)(x)

Therefore, a(U1U2)=(aU1)U2

Also,U1(aU2)(x)=U1(aU2(x))U1(aU2)(x)=(aU1)(U2(x))U1(aU2)(x)=a(U1U2)(x)

Therefore, a(U1U2)=(aU1)U2=U1(aU2)

For a more general result the Theorem is stated as,Put V,U,W to be vector spaces over the field K.

Assuming that the following mappings are linear, F:V→U,F′:V→U and G:U→W,G′:U→W.

For every scalar a∈K,

G(F+F′)=GF+GF′

(G+G′)F=GF+G′F

a(GF)=(aG)F=G(aF)

Therefore, the Theorem 2.10 is proved and a more general result is stated as,

Put V,U,W to be vector spaces over the field K.

Assuming that the following mappings are linear, F:V→U,F′:V→U and G:U→W,G′:U→W.

For every scalar a∈K,

G(F+F′)=GF+GF′

(G+G′)F=GF+G′F

a(GF)=(aG)F

=G(aF)

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 14 Answer

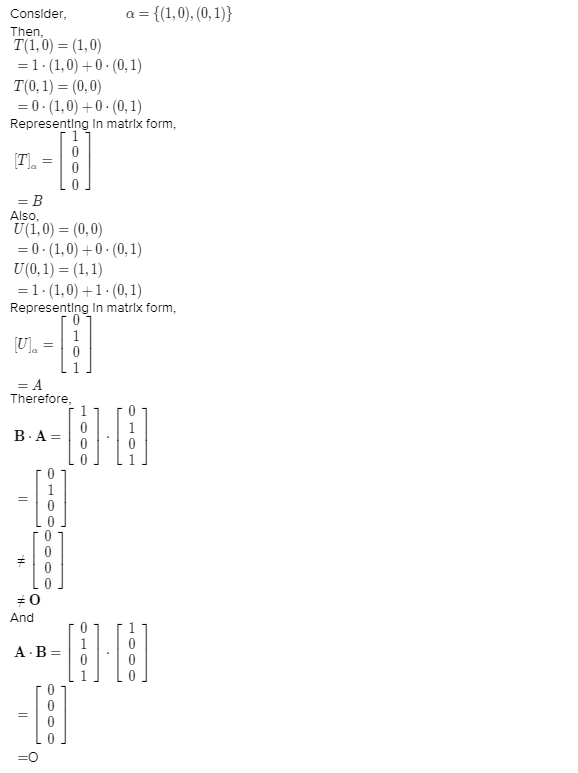

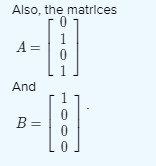

In the question, it is given that UT=T0 (the zero transformation) but

TU≠T0

Also, AB=O but BA≠O.

We are aske to find the linear transformations and matrices A and B.

First obtain linear transformations U,T.

Them using the linear transformations find the matrices A and B.

Given, UT=T0 (the zero transformation) but

TU≠T0.

Also, AB=O but BA≠O.

Therefore, the linear transformations,

UT=U(T(x,y))

=U(x,0)

=(0,0)

=T0

And

TU=T(U(x,y))

=T(y,y)

=(y,0)

≠T0

Also, the matrices

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 15 Answer

Given, A be an n×n matrix.

To prove A is a diagonal matrix if and only if Aij=δijAij for all i and j.

Consider when A is a diagonal mabtrix and show Aij=δijAij for all i and j.

Suppose when A is not a diagonal matrix and prove A is a diagonal matrix.

Given, A be an n×n matrix.

Consider A is a diagonal matrix,

Then, Aij={ Aij,I=j0,I≠j}

Aij={1.Aij,i=j0.Aij,i≠j}

Aij=δij

Aij for all i,j

Suppose that A is not a diagonal matrix,

There exist i,j,i≠j such that

Aij≠0

⇒0≠Aij

⇒0=0⋅Aij

0=0

This implies, A is a diagonal matrix.

Therefore, A is a diagonal matrix if and only if Aij=δijAij for all i and j is proved.

Exercise 2.3 Botes From Friedberg Linear Algebra 5th Edition

Page 98 Exercise 16 Answer

In the question, it is given that V be a vector space and let T:V→V be linear.

We are asked to prove T2=T0 if and only if R(T)⊆N(T).

Consider T2=T0 and prove R(T)⊆N(T) using the definition of null space.

Conversely prove T2=T0 using the definition of null space.

Given, V be a vector space and let T:V→V be linear.

Consider, T2=T0

As T0 is the zero transformation for every x∈V.

Since, T:V→V is the linear transformation this implies,

T(x)∈R(T) for every x∈V .. (1)

Applying T again,

T(T(x))=T2(x).

By hypothesis, T(T(x))=0.

Using the definition of null space,

T(x)∈N(T) for T(T(x))=0 .. (2)

From equations (1) and (2),

T(x)∈R(T)

⇒T(x)∈N(T)

Again, from the hypothesis,

T2(x)=0 for every x∈V we get,

T(T(x))=0

T(x)∈N(T)

Therefore, R(T)⊆N(T)

Conversely, assume

R(T)⊆N(T) .. (3)

And obtain x∈V

T(x)=0 .. (4)

Which is the definition for zero transformation and x∈V

⇒T(x)∈R(T)

From equation (3),

T(x)∈N(T)

Using the definition of null space,

T(T(x))=0

T2(x)=0 for all x∈V .. (5)

From equations (4) and (5),

T2=T0

Therefore, T2=T0 if and only if R(T)⊆N(T) is proved.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 17 Answer

Given: Let V,Wand Z be vector spaces, and let T: V → W and U:W →Z be linear.

Prove that if UT is one-to-one, then T is one-to-one. Must U also be one-to-one.

Assume that UT is one to one. We have to prove that T is one-to-one and whether U is one-to-one.

We will use the following example: Define U:R3→R2 such that U(a,b,c)= (a,b).

Assume that UT is one to one. We have to prove that T is one-to-one and whether U is one-to-one.

T(x)=T(y),x,y∈V

Since, the transformation U:W→Z is well-defined, and T(x),T(y)∈W

We have

U(T(x))=U(T(y))

(UT)(x)=(UT)(y)

x=y.

So it holds

x,y∈V,

T(x)=T(y)

x=y

Then the linear transformation T is one-to-one.

In the case when UT is one to one then U may not be one-to-one.

We will use the following example: Define U:R3→R2 such that U(a,b,c)= (a,b). And, define T:R2→R3 such that

T(a,b)=(a,b,0)

So

(UT)(a,b)=U(T(a,b))

=U(a,b,0)

=(a,b).

Since, UT is the identity function, it is linear and one-to-one.

kerU={(a,b,c):U(a,b,c)=0}

kerU={(a,b,c):(a,b)=(0,0)}

kerU={(a,b,c):a=0,b=0}

kerU={(0,0,c)}

From kerU≠{0}, the transformation U is not one-to-one.

The transformation U is not one-to-one.

Examples Of Exercise 2.3 In Friedberg Linear Algebra

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 18 Answer

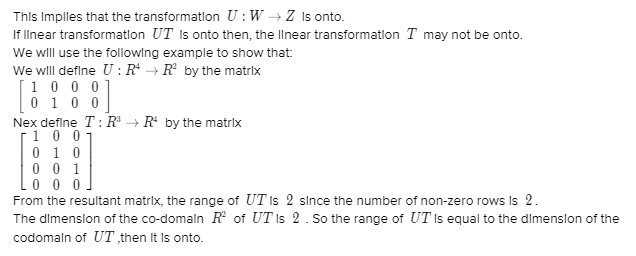

In the question, it is given that V,W and Z be vector spaces, and let T: V → W and U:W →Z be linear.

We are asked to prove that if UT is onto, then U is onto. Must T also be onto.

Suppose that UT is one to one. Then prove that T is one-to-one and whether U is one-to-one.

Use the following example: Define U:R3→R2 such that U(a,b,c)= (a,b).

Assume that UT is onto. We have to prove that U is onto and whether T is onto.

As U:W→Z is a function, take z∈Z.

From T:V→W, and U:W→Z, the transformation UT:V→Z is a function too.

Since UT is onto, z∈Z, there exist v∈V such that

(UT)(v)…(1)

T:V→W is well-defined so for v∈V,

T(v)=w∈W

From(1),

U(T(v))=z

U(w)=z

So for z∈Z, there exists w∈W such that

U(w)=z

The transformation U is not one-to-one.

Linear Algebra 5th Edition Chapter 2 Page 98 Exercise 19 Answer

Given: Let V,W and Z be vector spaces, and let T: V → W and U:W →Z be linear.

Prove that if T and U also be one-to-one and onto, then UT is also.

Let’s consider U:W→Z which is one-to-one and onto and T:V→W which is one-to-one and onto.

We have to show that UT:V→Z is also one-to-one and onto.

We will use the following example: Define U: R3→R2 such that U(a,b,c)=(a,b).

Let’s consider U:W→Z which is one-to-one and onto and T:V→W which is one-to-one and onto.

We have to show that UT:V→Z is also one-to-one and onto. Let (UT)(x)=(UT)(y),x,y∈V

Then we have

U(T(x))=U(T(y))

T(x)=T(y)

x=y

So for

x,y∈V,(UT)(x)=(UT)(y)⇒x=y

So UT:V→Z is one-to-one.

Let, z∈Z, since U:W→Z is onto, there exists w∈W such that U(w)=z

Since T:V→W is onto, w∈W, there exists v∈V such that T(v)=w

By substituting

T(v)=w in

U(w)=z we get

U(T(v))=z

(UT)(v)=z

So for, z∈Z, there is v∈V such that (UT)(v)=z

This implies UT:V→Z is onto.

Hence, UT: V→Z is one-to-one and onto when U: W→Z and T: V→W are one-to-one and onto.

The transformation UT is one-to-one and onto.